In a cardboard box lay two dozen toy soldiers and two toy military trucks. There was also a Medal of Honor citation for Army 2nd Lt. Robert Ronald Leisy, ’68, and 25 letters, some still smudged with the red dust of Vietnam.

Bob Leisy (pronounced Lacey) is one of eight University of Washington alumni who have received the Medal of Honor, in his case posthumously. He died in Vietnam during a firefight after using his body to shield his fellow soldiers—his friends—from a grenade. It was Dec. 2, 1969, and the 24-year-old political science graduate who had enlisted in the Army had been in Vietnam less than three months.

The box of letters that arrived at the UW’s Army ROTC earlier this year came as part of an agreement for the UW to inherit material housed in the Leisy Army Reserve Center at Fort Lawton as it closes over the next five years. The center, named in Leisy’s honor, is also the site of a particular tradition: Each Memorial Day, a Leisy friend from Queen Anne High School parks a can of beer and an affectionate note to the friend lost in war.

Perhaps that tradition of messages began with Leisy himself.

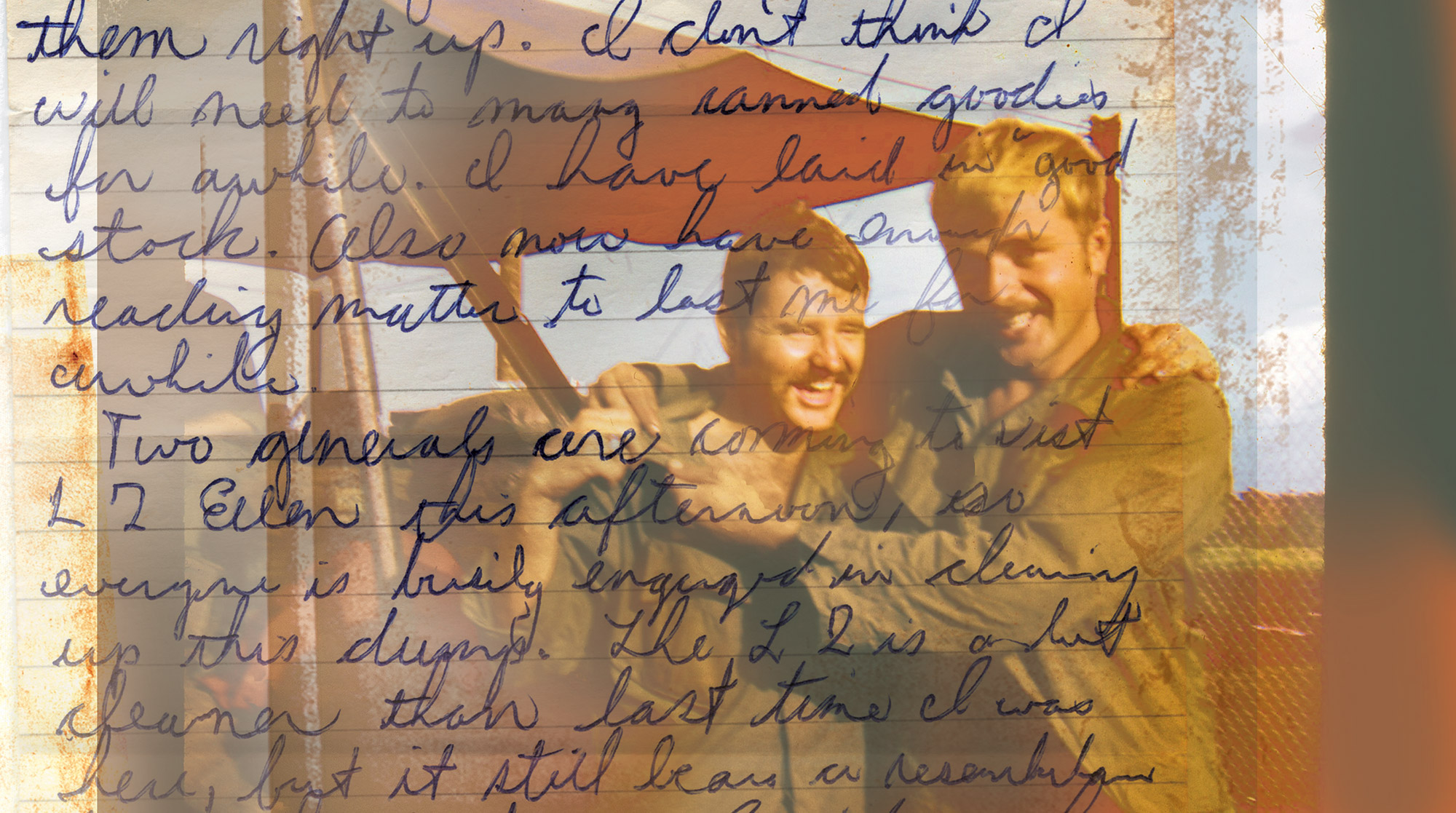

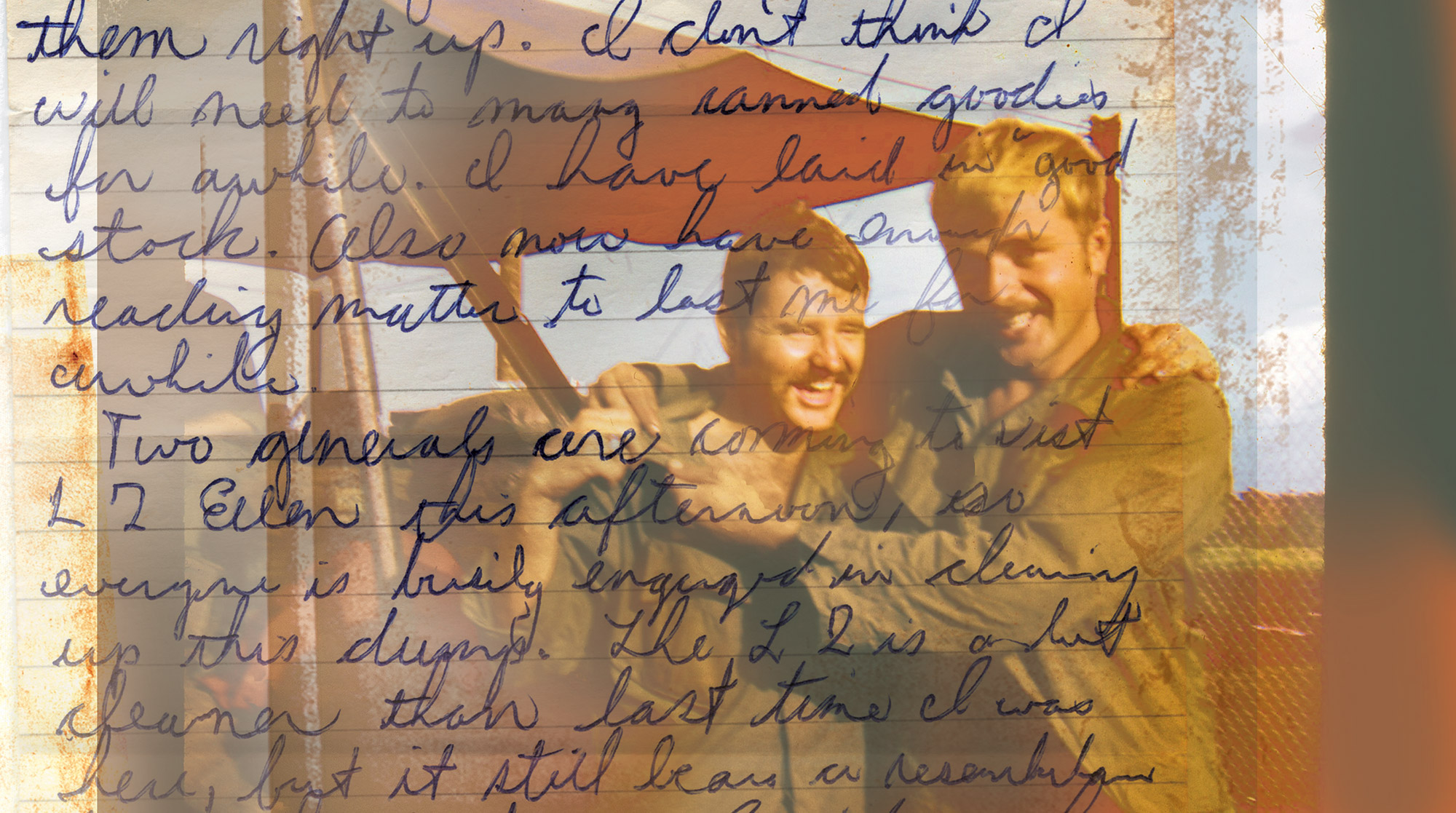

Between his late-September arrival in Vietnam and his death, Leisy wrote countless letters. Most of those in the box are to Leisy’s homemaker mother, Josephine, and his father, Arthur, but some are to friends from Queen Anne. From his station near Quan Loi, just north of Saigon, Leisy covered inexpensive notepaper with blue ink, telling the story of his new home in the jungle, far removed from the Pacific Northwest where he grew up. Talk of the weather and insects riddles his stories, from the first letters to his parents …

6 Oct. 69: It’s rather warm today. Humidity is terrific. Ma, you would really enjoy the insect life. It’s rich and varied. There’s a large roach over here several inches long, just the thing for you.

… to his last missive from the field, sent to friend John Wedeberg, ’73:

1 Dec. 69: The wonderful fauna and wild life really round out your tour: leeches, tiger leeches (one inch and up), pythons, bamboo vipers, other snakes, poisonous centipedes, scorpions. The biggest I’ve seen was a good nine inches from stinger to claw tip. And of course mosquitoes. I love the out of doors. If I survive, I will never go anywhere without a roof over my head.

Bob Leisy

Always, there’s the red mud and red dust painting his letters.

6 Oct. 69: There is red mud everywhere. I just got some on this letter.

11 Oct. 69: The biggest hardship so far is trying to keep reasonably clean. Mud, dust, dirt everywhere, plus the fact that you sweat all day long.

22 Oct. 69: Dear M & D: Just a short note. Rather dirty right now. We are building a landing pad here in the woods so a chopper can come in and take us out. Will be going back to LZ Ellen—a base NW of Quan Loi. I’m not surprised it is not on the map. It was just a tiny village until we moved in.

Leisy may have been a soldier—one who very courageously sacrificed his life—but the boy in him shines through. In addition to the ribbing he gives his mom, his letters are filled with references to the cavalry mustache and sideburns he was growing and to food and beer, barbecue and his beloved football.

The 1969 season was not going well for the Huskies, and news of their losses was slowly filtering across the world to Leisy, thanks to letters from friends, subscriptions to the Sunday Seattle Post Intelligencer and news from The Stars and Stripes.

21 Oct. 69: Thanks for the clippings. UW is really hurting! Wish I could see them, but maybe it’s not worth it.

25 Oct. 69: I just can’t believe the UW scores. Poor dogs.

His letters are also filled with references to his childhood stuffed animal, “Bugs,” and in many he asks about the rabbit, saying it’s good he didn’t come along. Still, one can’t help but wonder how serious his joking is as his tour continues.

4 Nov. 69: Ask Bugs if he would like to come visit me. He could come in a box. What a trip for the Rabbit. I’m sure he would regret it the minute he landed!! Most people do!

The letters become more serious throughout his tour.

22 Oct. 69: The biggest problem in this DIV is malaria. Far more people are put out of action by this than the enemy.

Mosquitoes weren’t Leisy’s only problem. Two days after that letter, while members of Leisy’s unit, Bravo Company, were unloading a helicopter, a downblast from the propellers kicked loose a nest of hornets, which stung Leisy several times.

By evening he was vomiting and incoherent. “He scared the daylights out of us,” said Dan Houmes, Leisy’s radio telephone operator at Landing Zone Ellen.

Apparently, Leisy never told his parents what happened. Instead, in a Nov. 2 letter, he says he has a bit of the flu, including a sore throat and a swollen tongue. He also describes a visit with some Vietnamese nearby: “The other day some of us went up to a village north of here. We passed out goodies to the kids, but the big attraction was a Polaroid Land camera. The people, especially the little kids, loved to have their picture taken.”

If the flu was a lie of omission meant to protect Leisy’s parents, it was not the last he would tell them. He also had them believing life in Vietnam was more like a boring holiday than a war, and that he was relatively out of danger.

In a Nov. 8 letter, for example, Leisy wrote, “It is so quiet over here it’s hard to believe a war is supposed to be on.”

***

It couldn’t have been entirely quiet. Houmes recalls a day in mid-October when Bravo Company combed a Michelin rubber plantation for North Vietnamese soldiers. The patrol was relatively uneventful until the moment the enemy opened fire, pinning Bravo men who were in front.

Houmes took cover behind a rubber tree, but Leisy charged forward about 80 feet before issuing a polite invitation back to Houmes: “Would you care to join me up here?”

Instead of waiting for a response, Leisy pounded forward again, directing a counterattack, calling in air support, “getting us through without casualties,” Houmes recalls.

Again, nothing about the attack exists in Leisy’s letters to his parents. Certainly, some letters could be missing, or it could be more evidence of Leisy’s pattern of protecting his parents. He had also led his parents to believe he had a “beer-in-the-rear” assignment away from the fighting, though in actuality Leisy led a rifle platoon that tracked North Vietnamese soldiers.

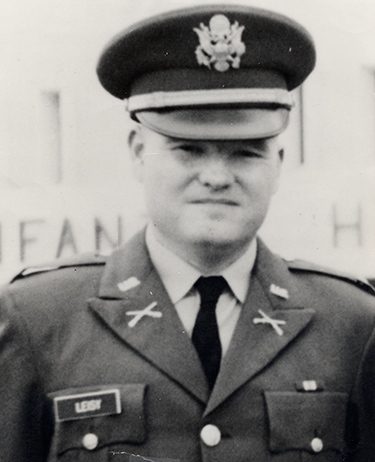

Bob Leisy’s military portrait.

Bill Hunt, the executive officer of Bravo Company, recalls that one day Leisy questioned him closely about executive officer duties. Then, in a subsequent letter to his parents, Leisy informed them he was the executive officer of Bravo Company, responsible for such matters as paperwork.

“He wasn’t telling the truth,” Hunt says, “but maybe he was doing it for the right reason. What a shock it must have been for his parents to find out what he was really doing.”

Leisy did let his parents see a few things:

21 Nov. 69: This letter is getting very dirty because choppers keep flying over and spraying me with dirt and dust. The B-52s have been blowing the fool out of the area around here. They strike at night, and the whole earth trembles and shakes. Flying over the country is like looking down on the face of the moon. Bomb craters are everywhere.

While Leisy ends the letter casually, with talk of a barbecue, a note written on the same day, to friend Verne White, offers a sharp contrast.

21 Nov. 69: The war is going full steam ahead here. Lull! HA. I feel about 10 years older—think I’ve aged that much. Have discovered real, honest, naked fear. But I gain an appreciation for the small things in life that I never thought of before.

It is the difference between his last two letters, dated a day before his death, that exposes the chasm between the front Leisy was putting up and the front he was writing from.

1 Dec. 69: Dear Dad: I work mainly at LZ Ellen now. My work mainly involves just B Co.

I want to tell you I don’t think I will stay in the Army. There are a great many things I like about the particular job I now have. But I think the promotions after the war is over will be extremely slow … Everything is going fine. I’m well and happy. I’m just sorry I’m going to miss Christmas. We will all have to make up for it next year.

The letter Leisy sent to friend Wedeberg that same day tells another story.

1 Dec. 69: Dear John, It’s really 30 Nov. but it will be 1 or 2 Dec. before I see any chopper to put this letter on. Airmobile? My ass! Foot CAV. We hump everywhere, carrying everything on our back. About 90 lbs of gear supported by only 2 feet. The Co. is supplied by chopper once every 3 days, a hot meal (sometimes) more C’s & water. It’s a great life.

My nerves are calming down now. We had some nasty contact and some rather hairy experiences on our last mission. Thought I’d bought the farm for sure.

May I suggest that you stop over at my folks’ place and have a look at some of the pictures I’ve sent home? I just request that you tell my folks I have a soft rear job—FAKE IT.

Those letters, stark in their contrast, would be the last Leisy would send his friends and family.

***

On Dec. 2, during a Bravo Company reconnaissance mission, North Vietnamese guns trapped one of Leisy’s patrols—eight to 12 men. Though by all estimates the platoon was considerably outnumbered by North Vietnamese soldiers—by as much as 10 to 1 according to a follow-up report—Leisy took the roughly 30 remaining men in his platoon to rescue the others.

Working their way through the jungle, Leisy spotted a sniper launching a rocket-propelled grenade at the men. With no time to escape or even yell a warning, Leisy jumped on Bernie Baillargeon, who held the platoon’s radio telephone. Baillargeon sustained a leg wound; Leisy’s wounds were more serious.

Gene Clark, the then-21-year-old medic, reached Leisy fast. Rolling him onto his back, Clark knew he was in trouble. Leisy’s hand was nearly blown off and the grenade had torn a hole in his leg, near his groin. And he was losing blood fast.

Two weeks earlier Clark had joked with Leisy, saying that with so little time left on his assignment in Vietnam, he wasn’t taking chances. “When we hit the s—, I’ll be too short. I’m not gonna be making house calls.”

Lying on the ground, it was Leisy’s turn to tease Clark: “I thought you said you weren’t gonna make house calls.”

“Yeah, well, things change.”

“I’m not gonna make it, am I, Doc?”

“You got a hole in your leg,” the medic confirmed, “but you’ll make it.”

Then, Leisy refused medical attention and told Clark to care for others, knowing full well, Houmes says, he wouldn’t survive. Yet as he lay dying he continued giving orders, through Baillargeon, his radio operator, and encouraging his men.

“He not only saved Bernie’s life, but mine as well and every other member of Company B,” Houmes recalls. The sniper, says Houmes, wasn’t just aiming at the men; he was trying to knock out the radio. With the first and third platoons separated by a couple of kilometers and without communication, the men would have been cut off from the rest of the company, with no artillery or air support. They would have been massacred.

Leisy’s parents may have never known what their son was really doing in the Vietnam war, but his act of selflessness and bravery printed a message in the hearts of the family, friends and fellow soldiers he left behind.

Read some of the letters home from Leisy: