License to innovate License to innovate License to innovate

Bright ideas frequently emerge from the University of Washington. For 40 years, the Washington Research Foundation has been making them pay off.

Bright ideas frequently emerge from the University of Washington. For 40 years, the Washington Research Foundation has been making them pay off.

Yeast is a fungus, a simple single-celled microorganism. And baker’s yeast is a routine ingredient found in kitchens everywhere. But something so mundane and so abundant is also at the heart of a major research discovery that has saved millions of lives and, in the last four decades, brought in more than $445 million in revenue and more than $100 million in grants to power research across the University of Washington.

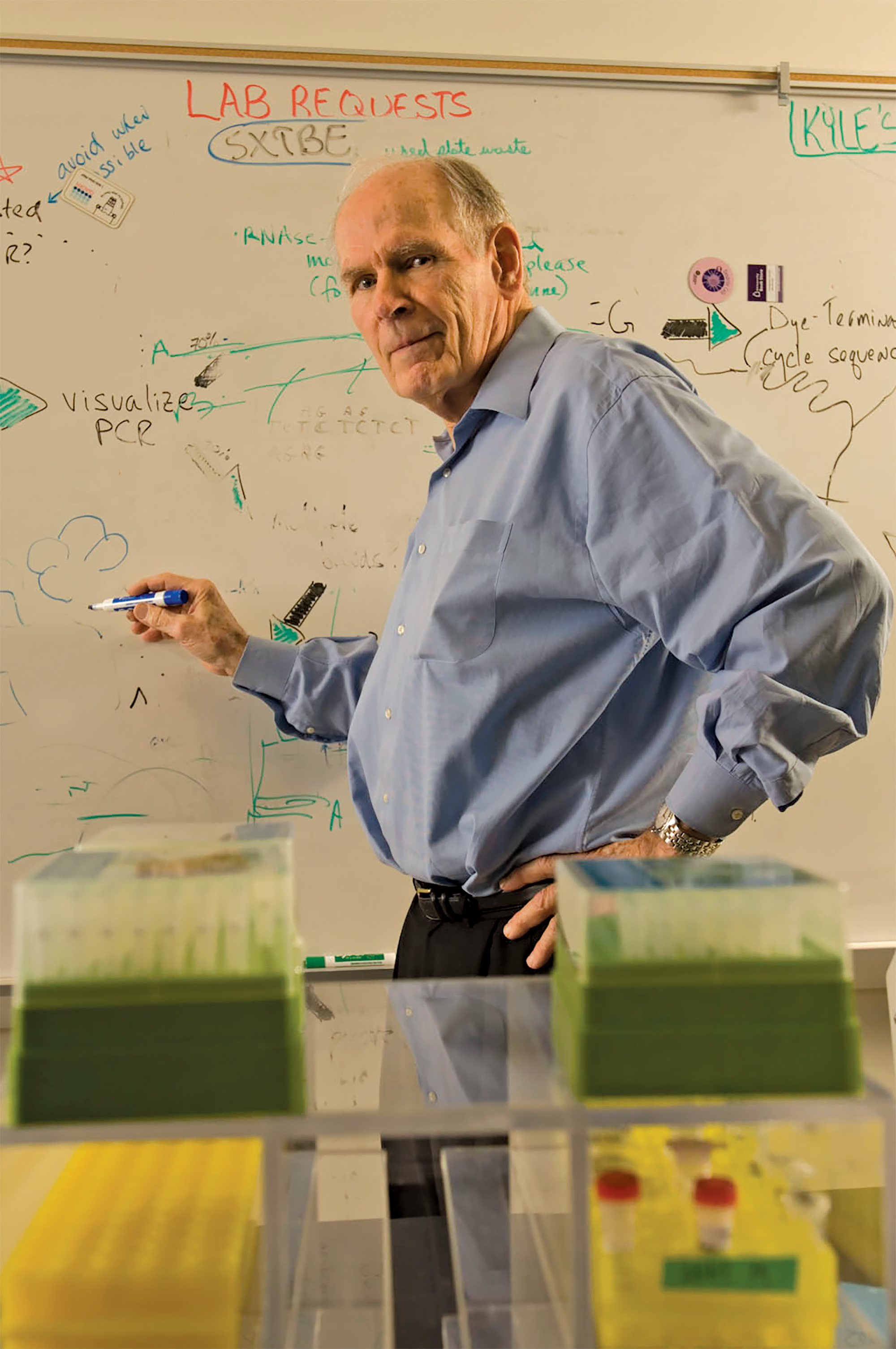

In the late 1970s, Professor Benjamin Hall and a team of students and researchers in his biology department lab discovered that baker’s yeast was useful in transcription, the process of copying a segment of DNA. After putting human DNA into baker’s yeast, they could transcribe genetic information into messenger RNA, which then could be translated into human protein.

Working with postdoctoral researcher Gustav Ammerer and colleagues at a biotech company in the Bay Area, Hall developed a general method for producing genetically engineered proteins. The method would lead to making insulins and some of the world’s most important vaccines.

That science is just the first chapter of one of the state’s first and largest research-supporting foundations. The rest of the story includes timing, attention and efforts to protect and patent discoveries made in UW labs. In 1980, the Bayh-Dole Act was signed into law, enabling universities to claim a portion of the revenues generated by discoveries and inventions developed under federally funded research programs. It was the dawn of the biotech era, and pharmaceutical and medical technology companies were already trolling campuses across the country looking for new discoveries to turn into businesses.

Enter W. Hunter Simpson, ’49, a former IBM executive and local business leader. He was also an ardent supporter of the UW, which he described as the Pacific Northwest’s “most precious asset.” From the perch of regent for the University, Simpson had a sweeping view into research on campus. He saw the potential of bringing discoveries and inventions from UW’s labs to the commercial sector, but he worried that the University wasn’t positioned to protect the discoveries and inventions—the intellectual property—developed there. “He was particularly concerned at that point because some ultrasound technology sort of slipped out under the door to a company and the University got nothing for it,” says Tom Cable, a close friend and business colleague. “It just really rankled him.”

At the time of the WRF’s founding, Microsoft had just incorporated in the state of Washington and the national ideas of a ‘private foundation’ and a nonprofit sector were only about a decade old.

One Sunday night in 1980, Simpson called Cable at home and described a visit he had with Hall. Hall was concerned that Genentech, a biotech company in South San Francisco, was about to use and claim ownership of technology developed in his lab. “Hunter said, ‘Tommy, we have to do something about that,’” says Cable.

At the time, the UW had just one employee working half-time to manage all of the intellectual property from campus. There wasn’t much focus on protecting and patenting advances. “Hunter definitely felt that was a mistake,” says Cable. “So he said, ‘Why not form a foundation?’” Working with Cable and Bill Gates Sr., ’49, ’50, they formed the Washington Research Foundation. Nearly 20 years later, Gates Sr. would be one of the co-chairs and leaders of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the largest private philanthropic foundation in the world. But at the time of the WRF’s founding, Microsoft had just incorporated in the state of Washington and the national ideas of a “private foundation” and a nonprofit sector were only about a decade old.

“We really had no clue what we were doing and had no idea how to pay for it,” says Cable. But they knew they wanted to ensure the University benefited from the research it supported. The three founders persuaded Seafirst Bank to extend them a $500,000 line of credit, hired a manger and set up a “really dumpy office on 45th,” Cable says. They brought in Cable’s brother-in-law, an MBA with a depth of business experience, to pull the office together.

Their first mission was to file for patents for the Hall lab’s discoveries. Wasting no time, Cable and Hall flew to the Bay Area to the offices of Genentech to make the point that the company was profiting from Hall’s technology. “It’s a funny story,” says Cable. Bob Swanson, the head of Genentech, spotted the two men from Seattle in the lunchroom. Recognizing Cable, who had worked in the Bay Area before, Swanson made for their table. “He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ and I said, ‘We’re trying to keep you from stealing technology from the University of Washington,’” Cable says. That broke the ice and opened the opportunity to structure a deal. Genentech soon became a partner in filing for the first Hall patent and protecting the rights to the Hall discoveries.

The Hall patents didn’t get approved right away, though. While the foundation was formed and the patent applications were filed in 1981, the federal government didn’t approve the first patent until 1997 and a second in 2003.

Those delays weren’t a bad thing, says Ron Howell, who became the chief executive officer of the WRF in 1992 and retired in April. Because it looked like the patents would be granted, the foundation was able to immediately establish licensing agreements with dozens of biotech and pharmaceutical companies. The businesses used the yeast technology to create vaccines as well as diagnostic and therapeutic proteins. And they started paying fees and royalties years ahead of the patents. “This was actually a stroke of genius,” says Howell, quick to credit the people who established the process before he even joined the foundation. The WRF was signing licenses with private businesses as early as 1987. Once the patents did get issued, the licensing and royalties lasted another 17 years. “We had good intellectual property, we had good attorneys and we had good strategy,” says Howell. More than once, the foundation had to go to court to stop unauthorized businesses from using the yeast discoveries, and often prevailed.

When Howell joined the WRF, he didn’t know much about commercializing innovation. But as he evolved in his job, he came to understand the foundation as the partner to the UW that could move technology through the patent office and explore who in industry might need or want a license to something in the portfolio of intellectual property.

During Howell’s tenure, the foundation explored thousands of UW projects for possible patenting and licensing. Of them all, just two turned out to be worth more than $1 million and two more between $500,000 and $1 million.

Ben Hall’s patents were unusual. “The thing that made the Hall patents so rare is that it was a platform,” says Howell. “It was a way of taking a baker’s yeast and transforming it by putting in external DNA in such a way that the yeast would not die but would replicate and make all these copies and start translating that code to messenger RNA. And then it gets translated into a protein and that protein can be a blood coagulation factor or an enzyme for detergent or it can be insulin.”

“(Ben Hall) knew how much I didn’t know about the science, but he respected the fact that I was on a mission.”

Ron Howell, longtime CEO

Hall himself was impressive, says Howell. “He was a giant of a man. He was a skier, a hiker, a climber. He had gone to Harvard, and he had done the most valuable piece of intellectual property the UW had ever seen.” He also loved teaching and was brilliant at explaining his work. “He knew how much I didn’t know about the science, but he respected the fact that I was on a mission. I needed to understand enough to do the work of the WRF, to monetize his work for all the parties connected.”

Licensing from the Hall patents enabled the WRF to create an endowment and shift its focus beyond helping the UW patent and license intellectual property. It now taps into its $300 million endowment and provides grants and seed funding for new intellectual property and to speed up the development of new products and services, particularly in the life sciences sector. The WRF team became grant makers—primarily to the UW, but also to the Benaroya Research Institute, Washington State University and the Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center, among others. “Looking back, it was very fortuitous that we did what we did, even not fully knowing what we were doing,” Howell says of the move to set up a WRF endowment and use it to grant funding for students, research, startups and other needs. “Here we sit 40 years later, having funded all kinds of scholarships and chairs and buildings and postdocs, and it is just really cool.”

In 2014, the WRF team visited four UW departments to explore which programs should get major funding. Instead of giving to one, it supported all four—protein design, neuroengineering, clean energy and eScience—with a $31.2 million pledge. The following year, it pledged another $10 million to the UW Medicine heart regeneration program.

Today, the Seattle area is one of the national leaders in biotech business and research. Simpson’s son, Brooks, chairs the board of the WRF. And Cable and his wife continue their long-standing connection with both the foundation and the UW. Cable even chaired the UW Foundation for a few years. An important part of this history is the evolution of the foundation, the strengthening of the University and the burgeoning life sciences sector from the 1980s until now, says Sue Coliton, the interim CEO of the WRF.

“We think of our programs as a virtuous circle because they reinforce one another. Our tiered grant programs help researchers develop innovative ideas in their labs. As these ideas move out of the lab, we provide early stage funding to help them develop further. Any profits made from those investments are used for new grants and seed funding,” says Coliton. “Ultimately, our goal is to move discoveries into the public realm for the benefit of the public.”

This year, the WRF surpassed the $100 million mark in total grants given to the UW, putting the foundation in the company of donors that include the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ballmer Group and Paul Allen. Because the foundation focuses just on Washington, it has deep networks and knowledge of the talent and expertise within the state. “We live at the intersection of investment, philanthropy, academic research and the life sciences. This broad and complex network is one of our greatest strengths.”

Pictured at top: Ben Hall, whose patents helped seed an endowment that continues to promote new intellectual property and speed development of new products.