It began with a middle of the night brainstorm and ended with millions of salvaged lives, a slew of cutting-edge medical developments and a brand new field of study known as bioethics. It began 50 years ago with the Scribner shunt, a simple device that created a literal loophole in the death sentence doled out to those suffering with end-stage kidney disease.

“The shunt made long-term kidney dialysis possible,” says Dr. Christopher Blagg, executive director emeritus at Northwest Kidney Centers and professor emeritus of medicine at the UW.

“Hemodialysis had been around before then—we used it for temporary kidney failure—but the shunt meant chronic patients could be repeatedly treated. Before that, patients with irreversible kidney failure could not be treated.”

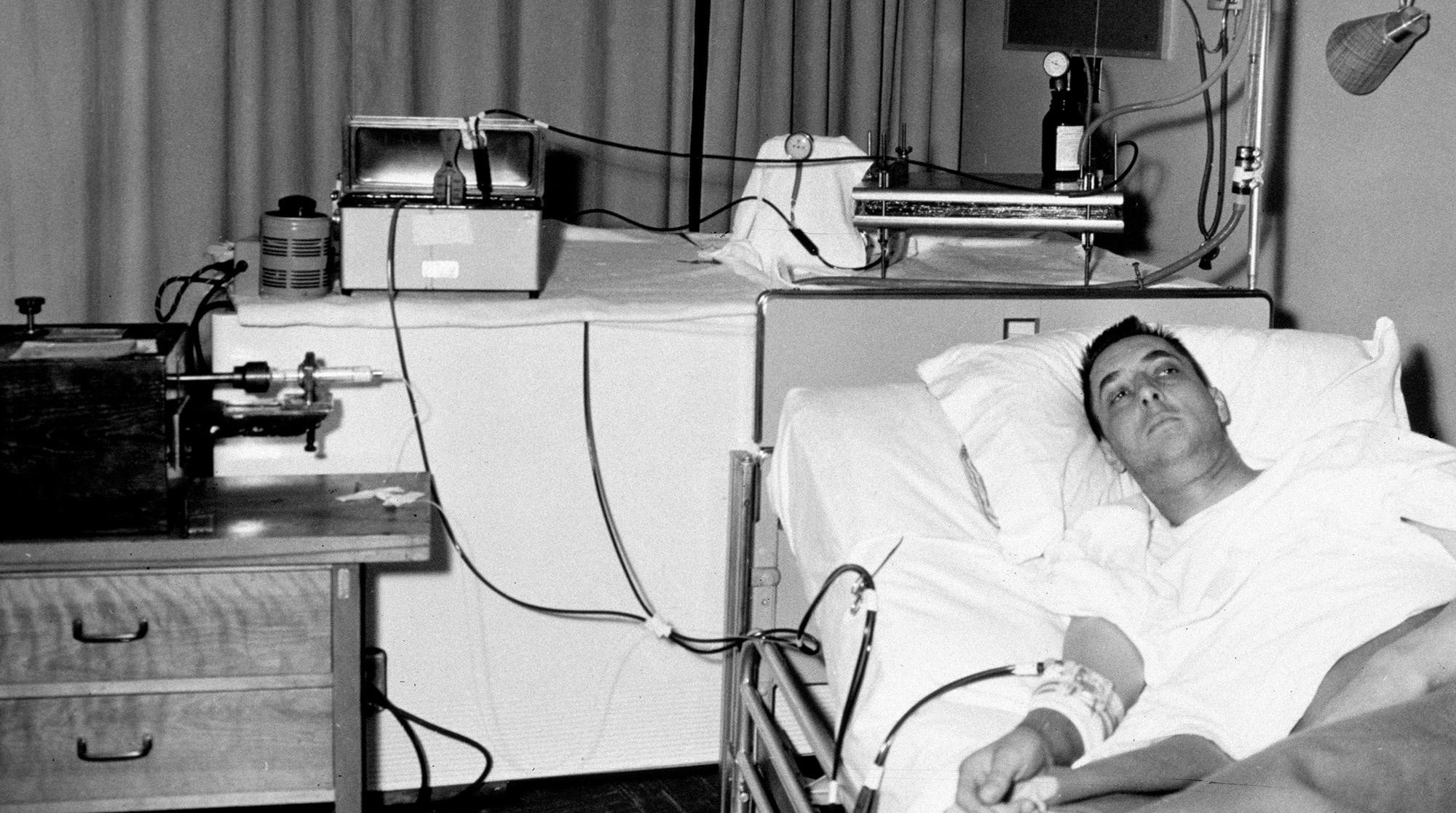

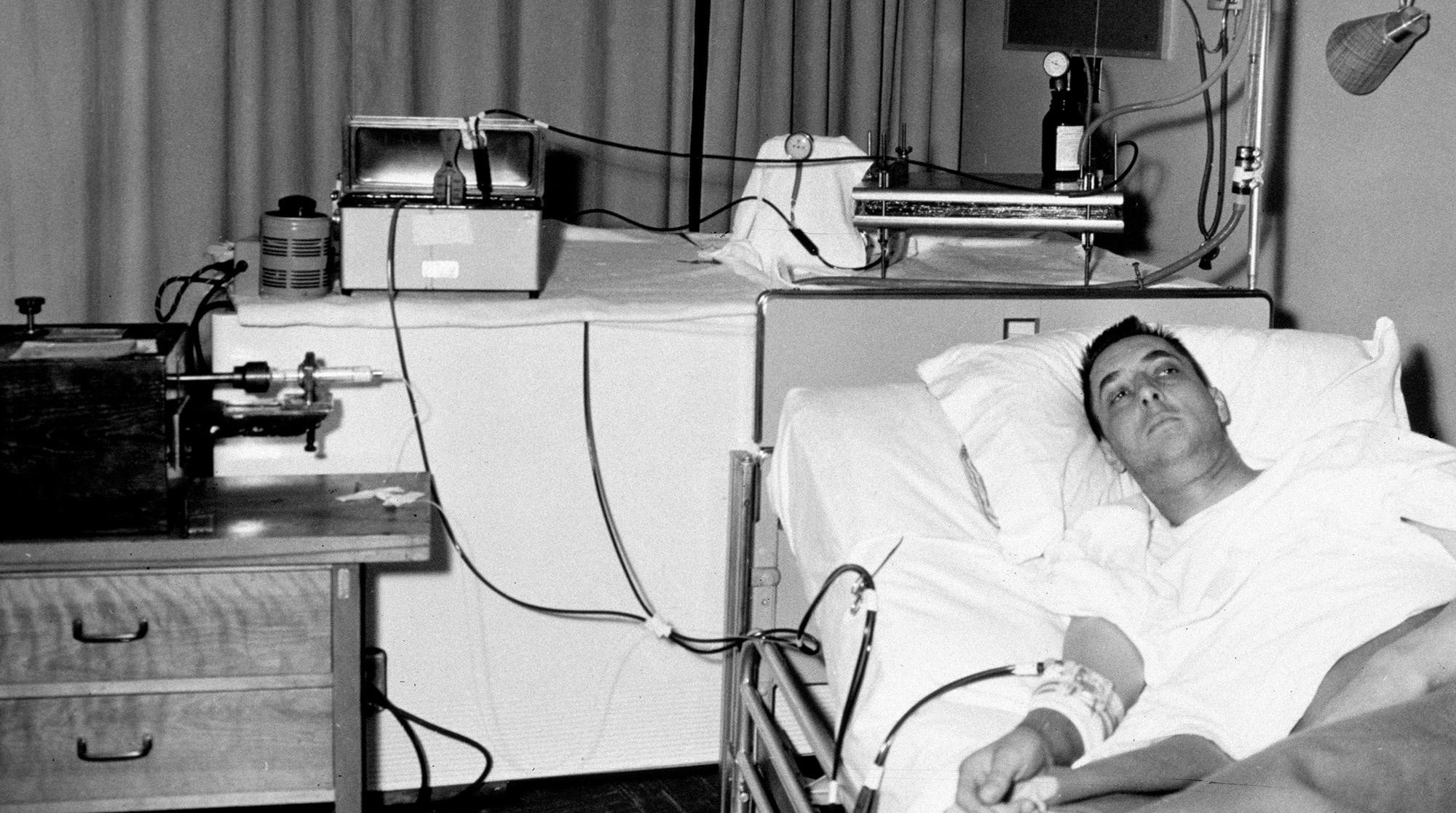

The UW School of Medicine’s Dr. Belding Scribner came up with an idea for a U-shaped arteriovenous tube that allowed doctors to “tap” a patient’s vein whenever they needed to cleanse their toxic blood with an “artificial kidney” or dialysis machine. The then-new material Teflon was used for the tube (its nonstick surface kept the blood from clotting), and the first shunt was implanted into the arm of machinist Clyde Shields in March of 1960 (pictured at top).

“This was the first attempt to keep people with kidney failure alive, and it was new to all of us,” says retired nurse Jo Ann Albers, ‘63, who worked with Scribner during those early years. “The first time I met Clyde Shields and saw dialysis being done, it was the middle of the night and I’d been called down to relieve the doctor. He told me to watch the drip chamber and if the blood stopped, to call him. Clyde always laughed later that he didn’t know who was more scared—he or me.”

For the first time, kidney failure was no longer an automatic death warrant: Shields and a few other patients implanted with the shunt that year survived. The formation of the world’s first out-of-hospital dialysis treatment center in January 1962—and a loud, upright piano-sized multipatient treatment machine dubbed the “Monster”—further upped the odds of patient survival.

But dialysis was extremely expensive and still considered experimental by many. Resources were limited and demand was growing. Who would receive this costly new treatment and who wouldn’t?

Enter the Admissions and Policy Committee of the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center (now Northwest Kidney Centers), which, following a November 1962 story in Life magazine, became better known as the “Life and Death Committee.” Selected by the King County Medical Society as a “microcosm of society-at-large,” the committee comprised a lawyer, banker, labor leader, housewife, minister, government worker and surgeon. Working anonymously and without pay, they chose who would and wouldn’t receive dialysis. It was the first time average citizens had been tasked with these kinds of moral, ethical and medical decisions.

Soon, the idea of such a committee drew the interest of ethicists. “One of the criticisms was that it was middle-class people selecting people like themselves for dialysis,” says Blagg. But, he argues, it was essential—because of the high cost of dialysis, the shortage of funding and the limited number of machines—that choices be made.

“We’ve developed a wearable kidney, but that’s sitting in my desk drawer because there’s no money to work on it.”

Dr. Suhail Ahmad

A panel of doctors established strict medical criteria—patients had to be between 18 and 45, for instance, and not have complications such as diabetes—but the lay committee had to narrow it from there. Blagg estimates that between 1962 and 1967 the committee was presented with 80 medically suitable cases, out of which 60 people were accepted and 20 rejected.

Nancy Spaeth, then 19, was one of those selected for treatment.

“You had to go through a series of appointments,” she remembers. “I had to do two days of psychological testing, and my mother had to see financial people and social workers. I never met with the committee—they got our information with our names blacked out—but I think they were basically looking for people who didn’t have other illnesses or psychological problems.”

In 1964, a 16-year-old girl—disqualified due to her age—was the impetus for another major innovation: the home dialysis unit.

Driven by patient devotion and a daunting deadline (the girl had an estimated four months to live), Scribner went to UW professor Albert “Les” Babb, the brain behind the multipatient Monster, to see if he could devise a portable single-patient unit. Soon, a “bootleg” operation was under way, with Babb and his team working on the home dialysis unit evenings, weekends, and whenever the dean wasn’t around (as a chemical and nuclear engineering professor, Babb had other educational commitments, but he was also friends with the girl’s father and felt compelled to help). Three months later, the “Mini-Monster” was complete, paving the way for the less expensive home treatments still used today.

By the 1970s, additional funding and new legislation made the Life and Death Committee obsolete, and further developments—such as kidney transplants and advancements in peritoneal dialysis—created even more options for patients with renal disease.

Today, 100,000 to 150,000 people develop kidney failure each year in the U.S., but thanks to the UW’s innovations, they still have a chance at life.

“Before all this, there was only one outcome, and that was death,” says Dr. Suhail Ahmad, senior medical director of Northwest Kidney Centers and professor of medicine at the UW. “Now, if properly taken care of, life expectancy can be normal despite dialysis and that’s a major achievement.”

No less major is the impact dialysis has had on the entire field of medicine, says Ahmad. “One thing many people don’t realize is that our team not only developed the shunt, they developed all the related dialysis technology as well as the methodology and management of kidney patients,” he says. “The impact has been huge. It has affected all branches of medicine—that’s how the central catheter was developed—and it was the start of biomedical ethics.”

Much like kidneys, though, the future of dialysis is paired: Along with new developments, there are old challenges. “We’ve developed a wearable kidney, but that’s sitting in my desk drawer because there’s no money to work on it,” says Ahmad.

“Advancements can’t see the light of day or benefit people if public funding isn’t available.”