I was heading to a 10 a.m. meeting. It was a beautiful day and I had the car windows down. My radio was on and they broke in to report the second plane hitting the World Trade Center. I felt “behind the curve” because I hadn’t known about the first plane. I hadn’t watched TV that morning and had no idea about the level of destruction. Then the President came on the air, saying that we had been the subject of an apparent terrorist attack.

Traffic is normally slow right around the Pentagon as the road winds and we line up to cross the 14th Street Bridge, heading into the District of Columbia. I don’t know what made me look up, but I did and I saw a very low-flying American Airlines plane that seemed to be accelerating. My first thought was just “no, no, no, no,” because it was obvious the plane was not heading to nearby Reagan National Airport. It was going to crash.

At that point time just sort of stopped. In retrospect, I’m amazed there were no car crashes, as those on the road with me just stopped and helplessly watched the plane crash. I pulled out my cell phone to call 911. I heard sirens and, not sure what to do, I called my mom who works at a newspaper in Illinois. She told me to calm down and keep driving. Fire trucks started to appear, so I and others on the road tried to move out of the way.

Operating mostly on autopilot, I drove to the office, keeping an eye and ear on the sky. I was positive another plane was coming any minute. Once you’ve seen the unimaginable, you believe anything can happen. They were already evacuating my building when I got there but I came up to the office and turned on the TV. The phone was ringing when I walked in and continued ringing. I was glad I was there so I could let people know we were all right.

As I kept replaying the scene in my mind, all I could think was, ‘This is all very wrong. It can’t be real.’

As I thought about it, aside from the incomprehensible feeling of the attack itself, the most shocking thing to me was that I could see the plane was a regular-sized, American Airlines flight. I was not aware from the early reports that hijacked domestic airliners were involved. As I kept replaying the scene in my mind, all I could think was, “This is all very wrong. It can’t be real.”

I stayed in the office until 1 p.m. The building was closed, but the city was in gridlock and I had to pass the Pentagon to get home, so it seemed better to stay. On my way home, I saw an Army attack helicopter in the air over a nearly deserted Capitol Beltway. It seemed surreal yet reassuring.

I deal with defense issues, among other things, for the University and I’m currently co-chair of the Coalition for National Security Research, so I know a lot of people who work in the Pentagon or meet there for business. I spent the next 24 hours, as so many people did, trying to track down all the people I knew who may have been in the area.

I, like most of the country, found comfort in the national day of remembrance and mourning Sept. 14. I have to say that Americans’ reaction to this attack has been as positive and strong as the attack was terrifying. Still, as I passed the Pentagon at exactly the same time a week later, I was struck by an eerie and very sad feeling.—Elaine McCusker, associate director, UW Office of Federal Relations, helps represent the University of Washington to the federal government.

***

I was in New York attending a meeting of emergency physicians, nurses and paramedics. Soon after the collapse of the second tower, we were deployed as a team to Ground Zero, about four blocks from World Trade Center Building 7, which itself collapsed about five hours after our arrival. Twenty-two of our group triaged patients and provided medical support to the police and fire departments.

The enormity of the destruction was exceeded only by the human courage and spirit of the victims. The few deranged terrorists were hopelessly outnumbered by the hundreds of thousands of common, everyday people responding in the only way they knew—with love and compassion.

The owners and managers of the 40-story building, in front of which we set up our casualty station, were single-minded: Give the medical team—and the police and firefighters—whatever they needed or wanted. Tables and chairs were brought outside and used for patients; easels and coat racks were IV poles; any food in the building was ours; medical equipment and supplies were freely removed from a nurses’ station in the building. Blankets and pillows appeared almost miraculously. A maintenance crew set up floodlights outside the building for our “hospital.” Other maintenance engineers became food service workers.

People brought bandages and medications from their own medicine cabinets in their apartments to give to our team.

People brought bandages and medications from their own medicine cabinets in their apartments to give to our team.

A doctor needed a bicycle to travel to a triage staging area. A local bicycle merchant gave him one of his new models. The doctor told him, “I don’t know when—or if—I’ll be able to return it.” The shop owner said, “Don’t worry about it.”

When you asked New Yorkers where to locate something, they wouldn’t tell you—they would take you. “Reasonable” replaced “legal.” If it was needed, you could, and should, do it.

Injured firefighters and police had only one thought as they were being treated—returning to help their colleagues. Tearful firefighters told us, “Don’t call us heroes. We’re only doing our job.”

Volunteers to help came out of the woodwork (like us, I guess): “I’m a dentist. Can I help?” “I’m a nurse. Can I help?” “I’m a psychologist. Can I help?” “I’m a CNA. Can I help?” “I don’t have any medical skills. I can write, and I speak Spanish. Can I help?” “I’m strong and willing. Can I help?”

Every time a group of more than five to 10 police or firefighters walked past our intersection or down the street, onlookers applauded.

A man driving a truck loaded with bottled water stopped at our medical station, unloaded his entire truckload of water, and drove away without a word being spoken to us.

As the World Trade Center Building 7 collapsed four blocks away and sprayed its debris toward our station, some people panicked and ran, and some fell to the sidewalk. But others stopped to help them to their feet to avoid being trampled by the crowd.

Acts of heroism were performed as if routine.

A homeless man spent nearly five hours at our intersection directing traffic—very successfully.

Back at our hotel—a Marriott, by the way—the building was opened for tired and injured people evacuating Manhattan by foot. A large meeting room (“Capacity: 2019”) became a shelter. Coffee, water and juice appeared. Food (the good stuff, too—including tortes and pecan pie) came from the kitchen. Blankets, pillows and towels were provided. A first-aid station was set up by some of our team. They even allowed us to establish a blood donation center with the help of local blood bank officials (not exactly “legal” but certainly “reasonable”). Furthermore, the Marriott staff even brought four refrigerators into the first aid room for the donated blood. At that, hundreds of donors had to be turned away.

The human spirit—an element of “common grace”—prevailed in hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers’ lives. News reporters want to create scorecards that tally only bodies. That’s the wrong way to count.—Clinical Professor of Medicine Leon Greene is a Seattle cardiologist who volunteers at Harborview Medical Center.

***

8:35 a.m.: The phone rings. It’s Lena, my best friend. She never calls this early. “You up?” she asks, her voice getting that shrill tone I recognize whenever she’s nervous or excited. I’m wide awake but still lazing around in bed. “No,” I answer. “But it’s okay. What’s up?”

“A plane just crashed into the World Trade Center,” she says rapidly. Lena is calling from her home office in Harlem, tuned into ABC’s morning news show.

“Whaaat?!” I gasp, grabbing the remote. I click on ABC, but the picture on the screen—showing a building gushing flames and smoke—is frozen. A squiggly pattern line is running across the screen. “Lena! The picture on Channel 7 isn’t moving. Are you getting reception?” She’s 14 miles north of the fire and smoke raging in Lower Manhattan. “Yeah, everything here is okay,” she says.

8:57 a.m.: I hit all the commercial channels quickly, repeatedly. Nothing but frozen images. Then I click to the cable channels. They’re fine. I know the tower on top of one of the World Trade Center buildings sends television signals to my part of Brooklyn. Suddenly, the picture on the screen starts to move. Reception is back.

The Manhattan skyline, as seen from Brooklyn as the towers fell.

9:18 a.m.: Out of nowhere comes another plane. “Oh, my God! There’s a second plane!” Lena shrieks. It heads straight for the second World Trade Center tower, crashes through and rips a gaping path that spews forth ravenous, consuming fire.

“Oh, my God.”

9:32 a.m.: Lena is braying at full throttle: “The Pentagon has been hit!”

“We’re at war,” I say calmly, as if the simple declaration of a fact gives order to madness. “Don’t say that!” Lena yells. “You can’t have a war without knowing who you’re fighting. We don’t know who did this.”

“Yeah, well that’s like saying a murder victim ain’t dead if you don’t know who the killer is,” I crack back. “We’re at war.” Lena and I then get quiet, on edge. A startlingly beautiful workday had gone cold and dark. By the time we hang up, two hours have passed—and so has life as we knew it before her call.

11:23 a.m.: The journalist in me kicks in. From the roof of my Brooklyn apartment building you can see Manhattan’s awesome skyline, with the World Trade Center’s twin towers in perfect view. The first tower has crumbled. I quickly dress and run up to the roof, just in time to see the second tower go down. Eerily, a towering inferno sinking to the ground in a billowing cloud of black smoke. There are others on the roof, as well: freelancers and the self-employed like me who work from home; housewives; the building superintendent; the Palestinian owner of the grocery store on the corner; two construction workers. We all stand mute, transfixed, traumatized.

Our little band of neighbors, merchants and workers reflect the great ethnic mix that has always given New York its dynamism and its grit. But as we watch—African-American, Hispanic-American, Arab-American, Euro-American—the hyphenated adjectives that mark our differences suddenly fall away like the towers themselves. Left standing is the American in all of us. We look at each other sadly, but also hopefully. Because we all know in that terrible instant the second tower collapsed that we are all in this together.

Postscript: African-Americans occasionally joke that we don’t want to be caught in the belly of the beast when it goes down. The “beast,” of course, refers to America with its own sins against humanity that demand a reckoning. But we also know that for all of its flaws and contradictions, the real greatness of America is that it inevitably tries to live up to its promise of freedom for everyone.

So yes, we are all in this together. The thousands of people lost in the World Trade Center attacks reflected the same ethnic mix as of those of us gathered on the roof. Our very diversity will prove to be our strength. Whether it’s the “homeboys” on my block who now fly the colors of the American flag with the same defiance they once flew gang colors, or the Irish-American firefighters in the station house two blocks away who lost six men (they were among the first on the scene when the World Trade Center went down), it will take all of America’s varied races, cultures and sensibilities, uniting as one, to prevail in the months ahead. Let us hope that, like New York City’s sometimes-flawed mayor, we will find in our darkest hour, our finest moment, and emerge stronger for having been tested.—Audrey Edwards, ‘69, is a contributing editor to More Magazine and former executive editor of Essence Magazine.

***

When Army Sgt. Maj. Gilbert Morales talks about his friend and colleague, Sgt. Maj. Larry Strickland, he can’t help but make a baseball analogy to the Baltimore Orioles’ legendary shortstop.

“He was the Cal Ripken of our career field, a real icon,” says Morales. “There is no real replacing him.”

Like Ripken, Strickland was planning to retire at the end of September. He had served 30 years in the Army, rising to the highest rank an enlisted man or woman can attain—sergeant major—and for the last 10 years was a personnel adviser to a series of three-star generals in the Pentagon.

Sgt. Maj. Larry Strickland

Strickland was an advocate for enlisted men and women amid the top brass of the Pentagon as they set policy on everything from promotions to pay raises to family leave.

“He did not hesitate to go to a three-star general and tell him, ‘You are about to make a mistake.’ That was his job. And he obviously did it well, since we went through four or five generals and each time we got a new one, he asked Larry to stay,” says Martha Carden, a civilian Pentagon employee who was Strickland’s friend and officemate for 11 years.

Only 19 days away from retirement, Strickland came to his Pentagon office on Sept. 11 even though he didn’t have to be there, Morales says. Because he was retiring, he needed to use up his annual leave or he would lose it. But he came in anyway, Morales recalls, because there was going to be an important briefing the next day on Army transformation. “He wanted to make sure those briefings were right,” the sergeant major says.

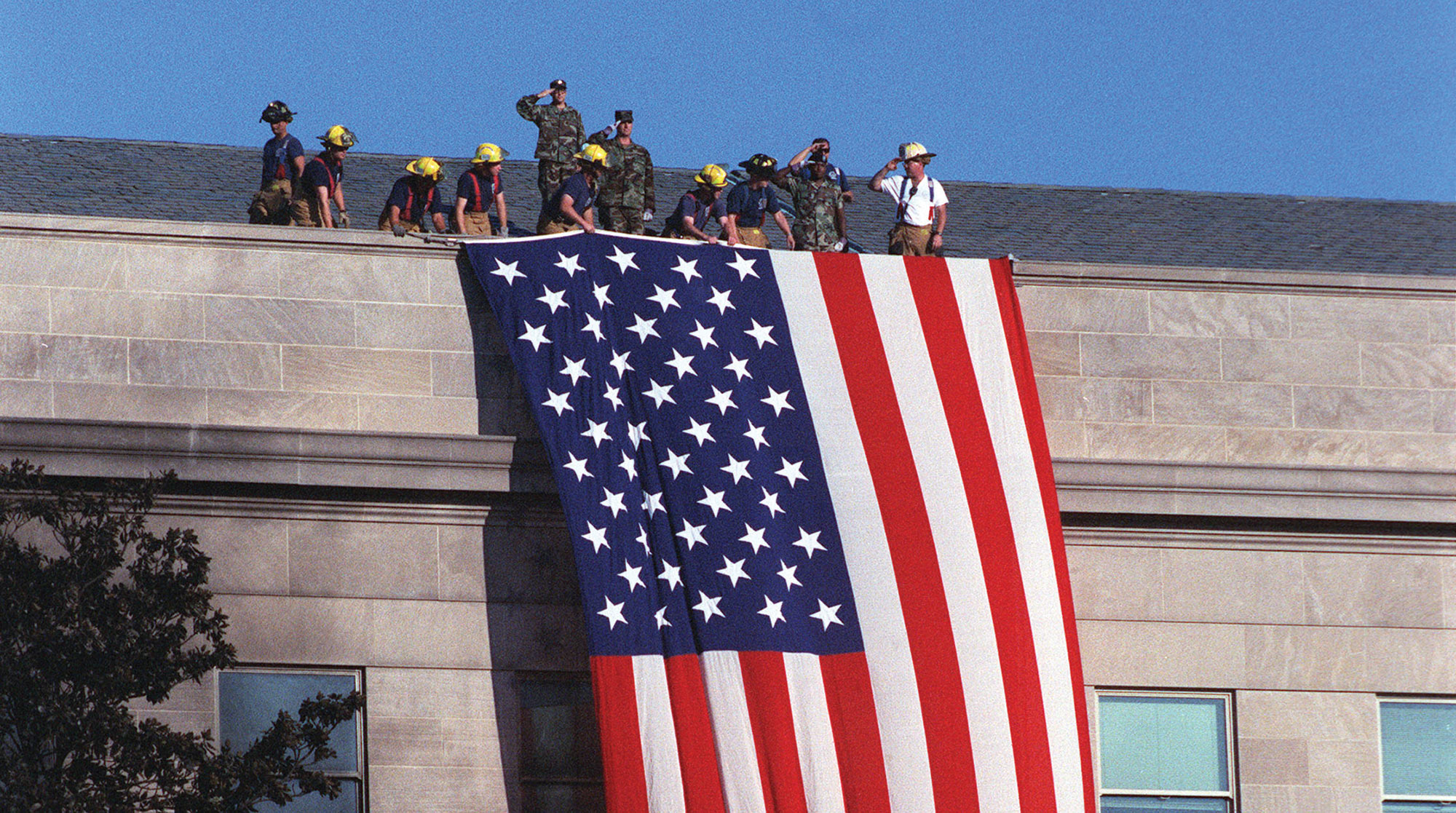

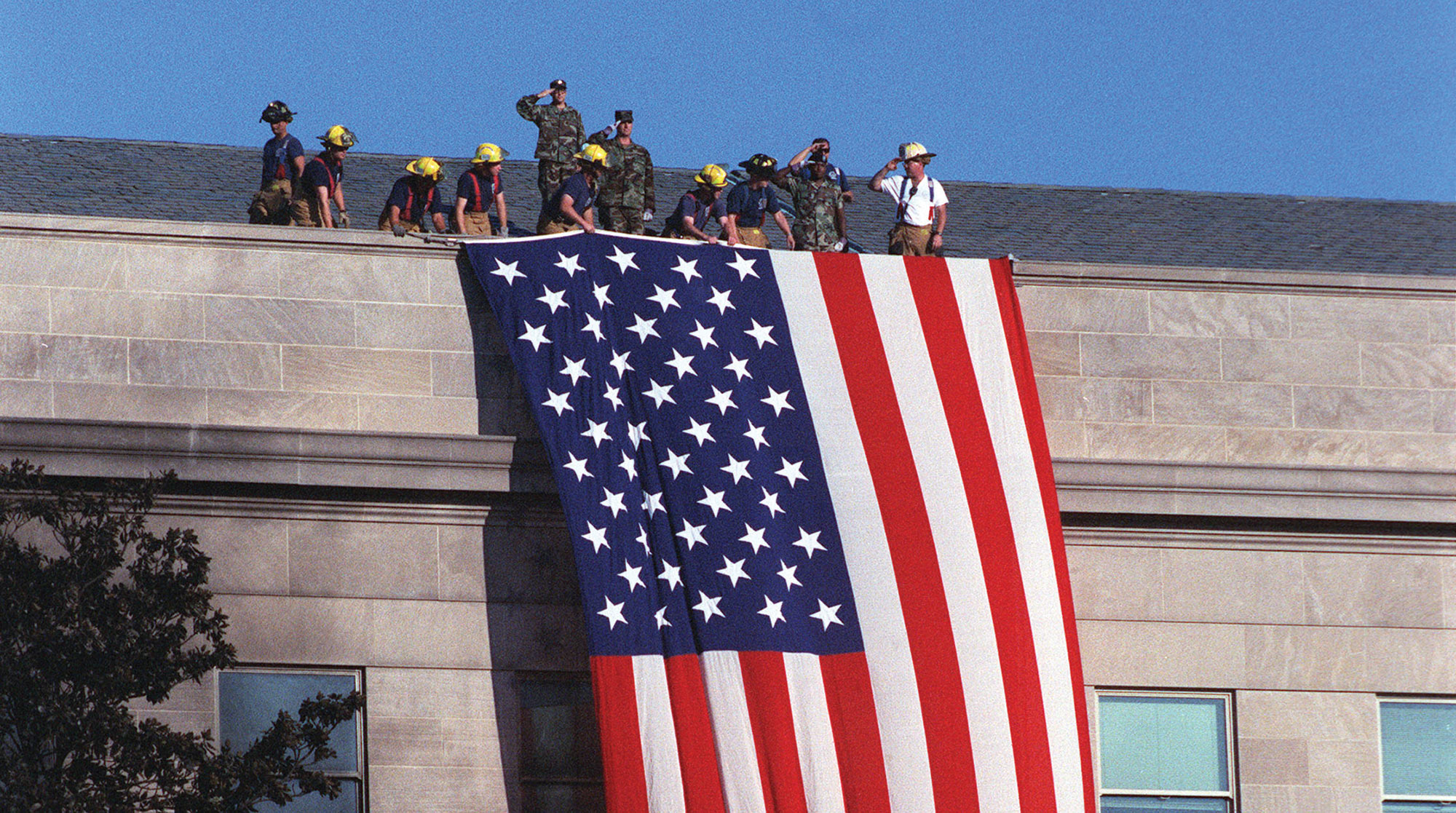

But the former UW student never made it to the briefings or his retirement. On that day American Airlines Flight 77, commandeered by terrorists, crashed into the west side of the Pentagon where he was working. He was one of 189 deaths in the Pentagon attack and the only member of the University of Washington community to die in the terrible events of Sept. 11.

Strickland, 52, is survived by his wife, Debra, a sergeant major at Ft. Belvoir, Va.; three children; Julie, Matthew and Chris; and a year-old grandson, Brendan.

Morales knew Strickland for 16 years, first meeting him when they were both stationed in Germany. Even then, Strickland was a top adviser in personnel matters. “He was fair, honest, never overbearing. He was receptive to different opinions and wasn’t locked into any one frame of mind, but he could sure make a decision when it needed to be made,” he recalls. “Sgt. Maj. Strickland always kept in mind what was best for the Army as a whole.”

Outside of the office, he doted on his year-old grandson and adored his wife. “They were made for each other, a perfect match,” says Carden. He was a gourmet cook and an avid gardener, she says, but his overriding passion was fishing, a sport he first learned with his father, by fishing in Puget Sound.

A native of Edmonds, Strickland was the drum major for the Edmonds High School marching band and later played for the Cascade Symphony. He came to the UW in the fall of 1967, planning to be an engineer and joining the Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity.

He was a “great big guy with a smile, always nodding, sage-like. He was a guy who seemed to understand,” says a fraternity brother, Tom Tivnan, ‘73.

“He seemed to lead a charmed life,” adds Bob Cline, ‘71, who shared a house and an apartment with Strickland once they moved out of the TKE house. “He was handsome and well liked, a take-charge kind of guy and a natural leader. He was one of those guys you just gravitated to.”

Strickland was so popular, the TKE president talked him into posing for a rush ad aimed at 1968 freshmen. His brothers dressed him up as Apollo and posed him in front of the University’s columns. “It was a fun part of our lives,” says Cline of their time at the UW. “None of us will ever forget it.”

But unlike most of his fraternity brothers, Strickland did not graduate from the UW. A history major two quarters short of graduation, Strickland left the UW in 1971 to join the Army. His mother, Olga, says his original plan was to get a teaching degree. But that changed due to a poor job market and he enlisted instead. During his Army career, he earned a bachelor’s degree from the Regents College of New York.

Though technically not an alumnus, Strickland was a proud Husky. “He followed the scores no matter where he was,” recalls his mother. “Whenever they did well, he had to have a new Husky shirt.”

Pentagon colleague Carden says he was also an ardent Seattle Seahawks fan, and she would have fun teasing him because she favored the Washington Redskins.

“He was one of the greatest guys I’ve ever known. He was like a brother,” she says. “He looked after me. If I was in difficulty, he was right there and would help me out. I miss him terribly.”—Columns Editor Tom Griffin wrote this memorial about Sgt. Maj. Larry Strickland, who would have been a member of the Class of 1971.

***

On the night of Sept. 12, I was a volunteer in search and rescue efforts and was able to approach Ground Zero. Although the search effort was concentrated in the immediate area where the towers had stood, the peripheral buildings were frighteningly dark and wore gaping holes in their façades.

When I took this shot late in the night, workers were craning their necks to look up at one of these adjacent buildings. Arms seemed to be reaching out of broken windows, waving lighters in the black, smoky night. Occasionally workers would break their silence and ask each other about it: Could those lights really be survivors trying to communicate with us?

Some of us wanted to investigate, even though it was too dangerous to get closer to the debris. But when the first rays of dawn spread to the building, another sliver of hope was lost: Metal rods, approximately the length of an arm, could be seen swinging in the morning wind. In the eerie work lights at night, the metal had played a cruel trick on hopeful but exhausted eyes. No survivors were found that night—or any night since.—Samantha Appleton, ’97, is a former Daily photographer and reporter who now free-lances photography for Associated Press and the New York Times.

***

On the morning of Sept. 11, I got into my car and turned on NPR. My mother-in-law had called a few minutes earlier to tell us a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. When the radio came on, they were describing the other plane crashing into the second tower.

It was a tough drive. I’m from New York. My brother works in Manhattan. My old roommate works on Wall Street. And my cousin works a block from the trade center. I went to the OR for lung surgery and my nurse informed me that the towers had collapsed. I began operating and the phone rang: There might be a set of lungs from a donor in Alaska.

Doctors once thought donor organs, such as the lungs, could only last four hours outside of the body. Now we are successful with organs that have been out eight hours or longer. Alaska is a stretch for us, but we’ve been doing retrievals from Alaska.

An Air Force F-16 Fighting Falcon. Department of Defense photo by Jeffrey Allen.

But the situation was different this day. My father was a Navy pilot and then flew for American Airlines. Through him I’ve learned a fair amount about air travel. I was fairly certain that the civilian air space would be shut down. Everyone in the room assumed this transplant simply would not happen.

But the people coordinating the transplant, LifeCenter Northwest, stated that they were able to get flight clearance. I called my dad and he voiced his concern. He told me that the more people involved, the more room there is for error. “I really think you are going to be vulnerable,” he said. Ultimately LifeCenter stated that the clearance was genuine and the window for flying was broad. I sought two additional assurances and then agreed to go.

We left Boeing Field in two separate planes. I was to do the heart and lung retrieval and Adam Levy the liver and kidney retrieval. It’s standard procedure. Because the organs I retrieve are more fragile, I have to get back quickly. On the way up, the pilot was quite nervous. He informed me that we were the only civilian aircraft flying in U.S. air space. We reached the donor hospital and the procedure went perfectly. The donor was a young man who had died tragically. The lungs were pristine. The heart was perfect.

We returned to the airport and met an executive from Alaska Airlines who had been stranded and obtained clearance to fly to Seattle with us. Upon crossing into Canadian airspace we were intercepted by a Canadian Air Force jet. Minutes later we were also picked up by a U.S. fighter. About 12 minutes from Boeing Field we suddenly changed speed and veered off course. We were flying over places we couldn’t recognize. At this point, the pilot wasn’t talking to us.

We landed at an airport I didn’t recognize. As we taxied closer I saw a sign: “Bellingham International Airport.” My heart sank. We were well into the time limit for reimplatation and we were far from the University. We were told that we were diverted for security reasons and, as I looked up, I saw two F-16 fighter jets, circling just above us. We found out later that while Dr. Levy’s return flight plan was OK’d, ours somehow got lost in the complicated events of the evening.

On the way back to the hospital, I told myself it was time to forget about all of this. I had to implant these organs quickly.

We had two, maybe three hours to go before the organs would run the risk of significant deterioration. As per standard practice, the transplant recipients were ready and waiting in the OR. I didn’t scream or yell ( I’m not like that). My focus was entirely directed toward alternate routes back: ground transportation, returning on our jet, or by helicopter.

I stated clearly to the airport officials that there was an absolute mandate for us to get back. “It is not negotiable nor acceptable in any way that these organs be allowed to deteriorate,” I said. If you don’t give people any wiggle room, it’s amazing what they can do.

The pilot was on his cell phone, I was on mine, my assistants were on theirs. The fellow from Alaska Airlines was trying to reach an FAA regional director he knew. Cell phone batteries started to go out, so we started swapping phones. The executive from Alaska Airlines got through to a senior FAA official and ultimately to a major at McChord Air Force Base.

We got very limited flight clearance. A helicopter would be fastest given it was now rush hour, so Airlift Northwest sent one to Bellingham. The pilot stated that he could take only one person and the organs. Since I had to put the lungs in, the choice was rather obvious. Twenty minutes later we landed at the helipad near Husky Stadium. The pilot said he couldn’t turn off the rotors. That meant I had to get out of the helicopter, hunch over and make my way to the storage unit next to the rear rotor blades to get the organs. I guess that falls into the “just when you thought the fun was over” category.

On the way back to the hospital, I told myself it was time to forget about all of this. I had to implant these organs quickly. I needed to be relaxed and focused. In the end, the lung transplants went extremely well and Dr. Gabriel Aldea did a very successful heart transplant. I later found out that the kidney and liver transplants went smoothly as well. In total, six patients got a gift of life from one donor.

Donor lungs are very fragile and tend to deteriorate quickly. To overcome that, and do a successful transplant, is really quite a miracle. It enables someone to simply breathe again instead of having to struggle for air.—UW Surgery Professor Michael Mulligan specializes in lung transplants.

***

When we are frightened or shocked, we rush to explain what alarms us in some belief that we can defuse it. Nothing is more difficult to understand than killers who destroy lives without one pang of regret. If we can place these aberrant personalities neatly into “boxes,” they don’t seem as dangerous. Less than twenty years ago, all murderers who killed a number of victims were referred to as “mass murderers.” The term “serial killer” came into common usage less than 20 years ago, and even these two definitions didn’t cover a third category: the “spree killer.” With the horrific tragedies of September 11, we must include a fourth group: “terrorists.”

The first three sub-groups have long been familiar to criminologists. Simply put, “mass murderers” kill many victims at once. These are the psychotic and suicidal killers who open fire in crowded restaurants, businesses, post offices and even schools. They usually die in the carnage, either by their own hands or in “suicide by cop” which they deliberately choreograph.

In the last decade, we have seen a burgeoning number of mass murderers, although they have always been with us. In September, 1949, Howard Unruh, a 28-year-old ex-Army sharp-shooter, destroyed a peaceful morning in Camden, N.J., as he left his mother’s house in the grip of paranoid delusions and shot 13 people to death. “I’d have killed a thousand if I’d had more bullets,” he said. Charles Whitman climbed the Texas Tower in Austin on August 1, 1966, and shot 46 people—killing 15—before police shot him fatally. In July, 1984, James Huberty announced, “I’m going to hunt humans,” and fired on a MacDonald’s restaurant in San Ysidro, California, wounding 19 and killing 21 people he didn’t know. The toll of victims of mass murderers mounts every year.

The “serial killer” is eminently sane but an anti-social personality “addicted” to murder for its own sake. All male to date, they kill one or two victims at a time over long time, with the incidents occurring closer and closer together until they seek victims almost every day. “Jack the Ripper” was a serial killer in 1882. Ted Bundy will always be the poster boy for serial killers. Like Bundy, who murdered dozens of young women in the mid-70s, or the still-elusive “Green River Killer” whose toll since July, 1982 is at least 50, serial killers often destroy more lives in their long careers than mass murderers. Having worked closely with Bundy on the Seattle Crisis Clinic phones, I know that serial killers present perfect façades to the world. And they are not at all what they seem to be.

The “spree killer” isn’t as well known. He is a combination of the first two types; he erupts with great rage, usually over some rejection, and destroys victims for a week or two until he is cornered. He almost always suicides at that point.

Every serial and spree killer has his own preferred victim profile, although serial killers stalk strangers and the spree killer begins with someone he knows who has rejected him and moves on to strangers who resemble that first victim. Charlie Starkweather headed west in January, 1957, with his 14-year-old girlfriend in tow, killing 10 people, including her family. Christopher Wilder, a Florida race car driver, cut a deadly swath across America in the spring of 1984, choosing a dozen young women victims at malls. And Andrew Cunanan left San Diego in July, 1997, headed to the Midwest to kill a lover who had rejected him, his rage accelerating. Strangers died, including famed designer Gianni Versace on the steps of his mansion in Miami Beach, Fla.

So, how can we categorize the terrorists who destroyed thousands of lives on September 11th? In some aspects they fit into the three acknowledged groups of multiple murderers. Like serial killers, they killed complete strangers. For all intents and purposes, they were sane. But were they addicted to murder for its own sake? I think not. Although they were suicidal, they were not mass murderers. They weren’t paranoid or enraged; they were coldly calm and confident.

Nor were the terrorists spree killers. Apparently, they had not been rejected. Not at all—they were chosen. And, for each, there was only one incident.

Serial, mass and spree killers are loners, with allegiance to no one but themselves. They believe in nothing but perverted pleasure, killing games, and in most instances, they present a deceptive mask to the world. Religious ferver and misguided patriotism are no part of them. They do frighten us, but our chances of becoming their victims are minuscule as they walk their isolated and abberant paths.

Terrorists are what I would call “manufactured sociopaths.” Born into a society where there is little hope for the future and surrounded by poverty, they are easy prey to be brain-washed. And they learn how to fool us. They are taught that religious wars are a good thing and that one would be lucky to be chosen. They are not loners at all because they see themselves as part of a grand plan, ordained by their God. Unlike the other multiple killers we have seen, the terrorists share a belief system with any number of co-conspirators. I have little doubt that they view Americans as unworthy of life and have no pangs of conscience when they destroy us.

I think that terrorists who joyfully ride a plane full of innocents into a building with thousands more innocents, believing that everyone will die, are akin to programmed robots. Someone very skillful and very devious has spent years turning them into manufactured sociopaths. Who to compare them with? I can only think of the kamikaze pilots of World War II.

If Osama bin Laden should order his armies of terrorists to till fields and build houses for the greater good, they would probably do so. The serial killer would not. No one has brainwashed him—other than himself. The spree killer would not. His own rage fuels him. The mass murderer would not. He answers to the voices in his head.

But, given any choice at all, I would not want to meet any of them face to face. Not one knows the meaning of compassion.—Ann Rule, ‘53, is the author of many non-fiction best-sellers on crime, including the just-published Every Breath You Take, the tale of an Oregon millionaire’s murder contract on his ex-wife.

***

At first, there couldn’t have been more than a hundred people there. We had all gathered in “Red Square” to take part in the national mourning ceremony at lunchtime on Sept. 14.

Then, silently, a group of about 10 students—some wearing red, white and blue clothing or ribbons—walked out to the middle of the square. Without saying a word, they grasped hands and formed a human circle. After a few moments, other people began to join them. First it was a few, then 10, then dozens, then hundreds. Soon, the long, human chain had enveloped all of Red Square, friends and total strangers alike holding hands and standing silently to remember those who died.

The silence was profound, given the number of people. For much of the 45 minutes, the only sound was the cawing of a lone sea gull swooping in overhead. But just before the bells rang at 12:30 p.m., in honor of the victims, a woman started singing “Amazing Grace,” evoking tears throughout the gathering. When the song ended, no one moved a muscle except to wipe away a tear, until another man in the crowd broke into “America the Beautiful.”

This time, many others, still holding hands, joined in. When that song ended, there was another round of heavy-hearted silence—until the roar of a commercial jetliner overwhelmed the quiet. In eerie unison, heads everywhere snapped upward, nervously looking at the sky as the plane passed out of sight. Then it was quiet again. But there was no peace.—Jon Marmor, ’94, is associate editor of Columns.

***

A sunny morning of complete ordinariness suddenly transformed by a lethal surprise from a clear, blue sky. The events of Sept. 11 inescapably seem to parallel the attack on Pearl Harbor. After both surprise attacks, we would discover, painfully, that our national security assumptions were too self-satisfied, too grounded in the belief that we had correctly anticipated the source and the direction of possible threats. In each case we failed to gauge the hostility our own actions had generated, had misjudged the audacity of our assailant.

In 1941, news of the Japanese attack was slow in reaching thousands of Americans in a time when radios and telephones were in fewer homes than televisions are today. In 2001, the attacks were seen in real time, the country linked electronically to every occurrence, every rumor. But the immediate responses do share some similarities. Shock, anger, fear and a surge of national feeling arose instantly. Both were “sneak attacks” producing demands for vengeance—and regrettable outbursts of abuse and suspicion directed against presumed representatives of “the enemy” within our own borders (Chinese in 1941, Sikhs now, for example). Significantly, where American leadership failed then to defend Japanese residents in the West, in the present crisis it has hurried to denounce racist reactions.

Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941.

But there are as many differences as similarities. In 1941 the country was already striving to reach a war-footing, conscripting men and churning out ships, planes and munitions at a rapidly rising rate. Most Americans anticipated the outbreak of war very soon—just not at Pearl Harbor in the Pacific. Before Sept. 11, our country was preoccupied with partisan political wrangling in Washington and concerns about the economy. Even today, there has been no call for a national war effort. Moreover, this enemy has a very different agenda from territorial hegemony: sowing terror and paralysis to cripple Western institutions themselves. Unleashing American productivity and energy will not, this time, be a sufficient answer.

In World War II, it gradually became apparent that while the war in the Pacific was going badly at first, and U-boats were ravaging shipping along the Eastern seaboard, any real threat to the United States itself was dwindling daily. Rumors of Japanese carriers standing off the mouth of the Columbia River or of Zero fighters flying over San Francisco quickly disappeared. In fact, America’s sacrifice in the war—some 400,000 dead—involved only six civilians within the 48 states. However shaken by Pearl Harbor and the first weeks of the war, Americans were certain who the enemy was, of their determination to gain a total, military defeat of that enemy and of their confidence in final victory by what Winston Churchill would later term “the proper application of overwhelming force.”

Today’s Americans look with far less certainty on the events under way while sharing the same kind of anger and bitterness as their predecessors. In this conflict, the Home Front is the target. Moreover, “the enemy” remains elusive and the prospect of a protracted, indeterminate kind of conflict pitting Islam against the West in a “clash of civilizations” is sobering. In an open-ended “war against terrorism,” victory is not defined by the overthrow of an enemy nation and destruction of its armed forces. Vice President Dick Cheney has cautioned that this war is not like previous wars “in the sense that it may never end. At least not in our lifetime.”

Nothing more strikingly separates today’s wartime mood from that of World War II than the ambivalence so many Americans are expressing about the very notion of waging war. In 1941 few questioned the necessity of war, much less the moral justness of a cause begun, as F.D.R. had reminded everyone, with “an unprovoked and dastardly attack.” Current reactions seem, by comparison, a stew of patriotic zeal, moral anguish and open denunciation of U.S. policy and practice throughout the world. As united as they are in denouncing the slaughter of Sept. 11, Americans are divided about the way to respond. In 1941, we were joining a “Grand Alliance;” a shaky and troubled alliance at all times but one sustained (just) by an unambiguous, shared determination to end the threat posed by the Axis states. We are now in a war on terrorism with an acute sensitivity to global perceptions of the United States. We are part of an amorphous coalition of anti-terrorist states which agrees on very little. Americans are also expressing an unprecedented concern over casualty limitation—ours as well as theirs. Unlike 1941, the matter of means and ends is far from settled.

Finally, we must approach comparisons with a revered past with great care. Nostalgia for World War II—which seems, in the glow of remembrance, a clearer, surer war—only makes our present circumstance more confounding for many Americans. It also obscures the complexity and uncertainty that a previous generation actually lived through at the time, when victory was not certain and the future held many terrors.—Military historian Randolph Hennes, ‘52, ‘66, recently retired from his position as associate director of the UW Honors Program.