At Bellingham’s Village Books, a display showcasing the “Best of the University of Washington Press” beckons readers with bears, baseball, Northwest art and narwhals.

“If not for UW Press, many of these books wouldn’t exist as brilliantly as they do–if at all,” says Robert Gruen, book buyer for the independent bookstore. “I love the very concept of university presses. It’s exciting to learn the latest of everything that is relevant.”

Kicking off its centennial celebration this year, the University of Washington’s press traces its roots to Edmond Meany’s 1915 Governors of Washington, Territorial and State. Meany, a graduate of the class of 1885, taught history and botany at the University. A fitting motto for the press itself, his dedication in the book is to one “advancing the cause of history.” In 1920, English professor Frederick M. Padelford’s The Poems of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey became the first book to carry the official UW Press imprint. Since then the press has published more than 4,400 titles, many of them groundbreaking work in fields like Indigenous studies, Asian studies and environmental history. “It’s energizing to be involved with new ideas,” says Larin McLaughlin, the UW Press editor in chief. “I find it exciting to help scholars and others share their work with a broader audience in a compelling way.”

The UW Press’s first book, “Governors of Washington, Territorial and State” by Edmond Meany, assembles 22 brief biographies of the first governors.

Covering the West

With as many as 70 new titles each year and press runs typically ranging from 500 to 5,000 per title, the press publishes 26 series. The most popular books, however, continue to be those focused on the Northwest. Bill Holm’s Northwest Coast Indian Art, first published in 1965, is an all-time bestseller. And 1945’s Ethnobotany of Western Washington has had the longest run in print. Through a century of enormous change in the publishing industry, the press has held fast to its mission of publishing scholarly books of enduring value.

“It’s about ideas. Ideas keep us alive. They keep us creative and make us and our world a better place,” says Gerald Baldasty, ’72, ’78, the UW interim provost and former member of the UW Press Committee. “Part of enhancing the life of a community is telling its stories. That’s what the press does.”

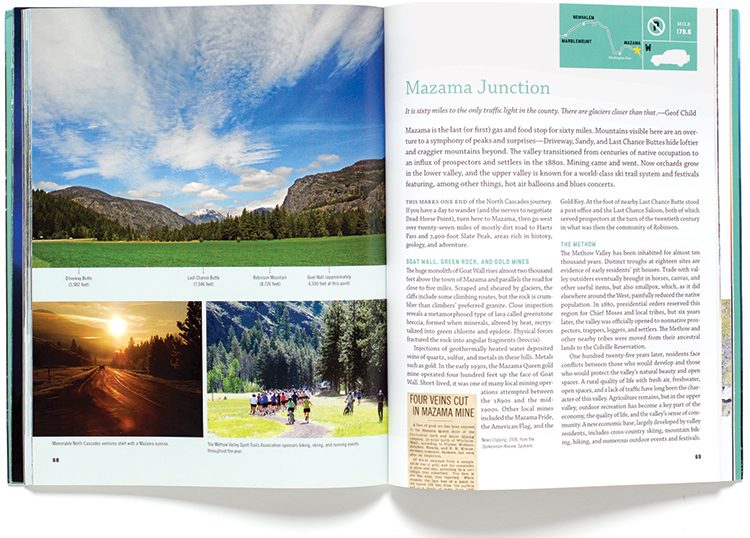

The largest scholarly press in the Northwest, the UW Press pays special attention to the five-state region of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Alaska. With the new Northwest Writers Fund, the press offers advances to local nonfiction authors covering topics of regional interest. The first title, published this fall, is David Williams’ Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography.

“Some presses focus more on scholarship and less on regional titles,” McLaughlin says. “It’s not that one is better than the other, but I think the regional gives us a way to really connect to the community.”

That community connection aligns with the University’s mission. Of the Association of American University Presses’ 138 members, only a “small crowd” has reached the century mark, says Peter Berkery, AAUP’s executive director. Part of UW Press’ longevity and success comes from its engagement with campus.

“In this day and age, when we talk about presses turning challenges into opportunities, smart presses are trying to align their activities as tightly as possible with their university’s mission,” says Berkery. “You look at the way they’re approaching regional publishing and it’s consistent with the interests and academic strengths of the university.”

Strengths and scholarship

A distinctive feature of university presses, compared to mainstream publishers, is the peer review process. Experts in a manuscript’s topic provide feedback. Once the authors have completed their revisions, the books are reviewed by a 12-person faculty committee. According to McLaughlin, the full process takes about 12-18 months. However, some projects can be in development for a decade.

The press editors identify historical strengths and then build on them by developing new series that connect with a new generation of scholars, says Nicole Mitchell, director of UW Press. “One of the great things this press has done, and wants to continue doing, is to be at the forefront of scholarship and identify emerging fields,” she says. By 2016, the press will have launched six new series within three years, including Feminist Technosciences, Indigenous Confluences, and Food, People, Planet.

The press is consistently advancing scholarship. “They’re famous for their books on Asian American and Native American studies and had a prescient emphasis on environmental studies,” says Judith Howard, 10-year member and current chair of the UW Press Committee. “These areas make sense considering the faculty expertise and the university’s degree programs.”

The wide-ranging publications focusing on Native American cultures are some of the most influential in the field. “It is the publisher for Northwest Coastal art from historic to contemporary,” says Ed Marquand, creative director and partner of Marquand Books, a longtime collaborator of UW Press. “The press has a longstanding commitment to Native American art since at least the 1930s and 1940s.”

The influence of these books extends into the region’s Indigenous communities, says Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, associate director for the Bill Holm Center for Northwest Art at the Burke Museum, and series co-editor for UW Press’ Native Art of the Pacific Northwest. While visiting Alaska for the opening of a new Native heritage center, Bunn-Marcuse encountered a Tlingit artist who said that Bill Holm’s Northwest Coast Indian Art was pivotal in keeping tribal artwork alive.

The Indigenous Confluences series takes an interdisciplinary approach by considering Indigenous people’s experiences through the lenses of environment, food justice, cultural expression and language. “There has been an explosion in the field of Indigenous studies in the past five to 10 years and it is very community engaged. It’s a broader audience, which now includes activists and policy makers,” says Coll Thrush, ’98, ’02, the series’ co-editor. “There are stories still out there waiting to be told. I think UW Press can participate in telling them.”

Chris Higashi, program manager for the Washington Center for the Book at the Seattle Public Library, values the press for presenting and preserving material that might not otherwise see the light of day. She and her siblings were raised hearing their parents had “been in camp.” It wasn’t until junior high that she realized that meant World War II Japanese internment camps. “From then on, I began reading a lot of novels, stories and poems about it,” Higashi says. “UW Press brought John Okada’s No-No Boy back to life [in 1980] and that’s a classic that breaks my heart every time I read it.”

No-No Boy was first published in 1957. It tells the story of Japanese Americans in Seattle who were ostracized during WWII. It is part of the press’ Classics of Asian American Literature series alongside masterpieces such as Monica Sone’s Nisei Daughter and Mine Okubo’s Citizen 13660. “Asian American studies didn’t really exist before the 1960s or early 1970s, so scholars had a hard time publishing in the field,” says Moon-Ho Jung, associate professor of history and editor of The Rising Tide of Color. “The press saw the potential of the field and was ahead of the curve. It had already published many books by the 1980s and 1990s when the field came to be recognized. These are important texts for teachers and students. More generally, though, they’re important for the larger public to read and recognize the history.”

Art and history

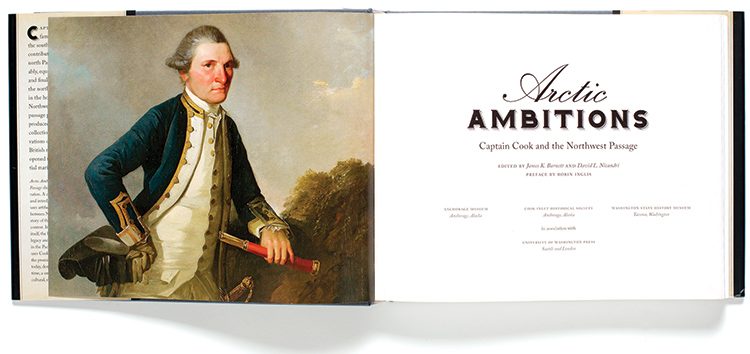

In the case of art books, UW Press excels at wowing readers with dynamic and colorful tomes. It also co-publishes and distributes dozens of new titles each year for museums and other cultural institutions.

Now with help from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the press is producing art historians’ first books in print and digital forms. The Art History Publication Initiative is in cooperation with Duke University Press, Penn State Press and the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fulfilling literary needs that large publishers overlook, the nonprofit press has a budget based on book sales, University support, endowments, grants and fundraising. The combination allows it to subsidize books that aren’t likely bestsellers.

“UW Press honors and supports books even if they won’t sell millions of copies,” says Kathleen Flenniken, ’88, former Washington State Poet Laureate and author of Plume, published by UW Press. “They take literature seriously that needs to exist because it contributes to our understanding of the larger world.”

The press is uniquely positioned in the regional literary ecosystem. Local independent bookstores maintain close ties and are eager to stock UW Press titles. “We really know these books. We read and care about them,” says Karen Maeda Allman of the Elliott Bay Book Company. “We know there is a market for them.”

Readers benefit from the less commercial titles, as do independent booksellers, says Rick Simonson, Elliott Bay’s senior buyer. In the 1970s, “the store was small, but people came in looking for books like Bill Holm’s and Victor Steinbrueck’s [Seattle Cityscape and Market Sketchbook],” says Simonson. “They were books about Seattle during a time of growing self-awareness and consciousness as a city.”

Today, Simonson sees the important role the press can play for a region again in flux. “The city is consumed with itself in its present, dynamic moment. It’s helpful to know some of the region’s history because there are patterns,” he says. “UW Press does books that tell the important stories of who we are by where we’ve been.”