A life study A life study A life study

A devastating fire makes painter

Grace Flott struggle for control

of her body—and her life.

Story by Julie Davidow | Paintings by Grace Flott | March 2020

Grace Flott has spent hours and days staring at her body—searching the ridges, gouges and lines in her skin for what it means to live with the scars.

With her body forever altered and her youth punctured by grief, she wondered who she would be and how would she become that person? How would her life take shape after surviving a deadly apartment fire as a UW undergraduate in Paris?

Nearly a decade later, Flott, now 29 and an artist, perches on a stool in her studio. The bright room with white walls and high ceilings is carved out of a former warehouse on Airport Way in SODO. She shares the space with another artist and is just settling in after finishing a master’s program at Gage Academy of Art.

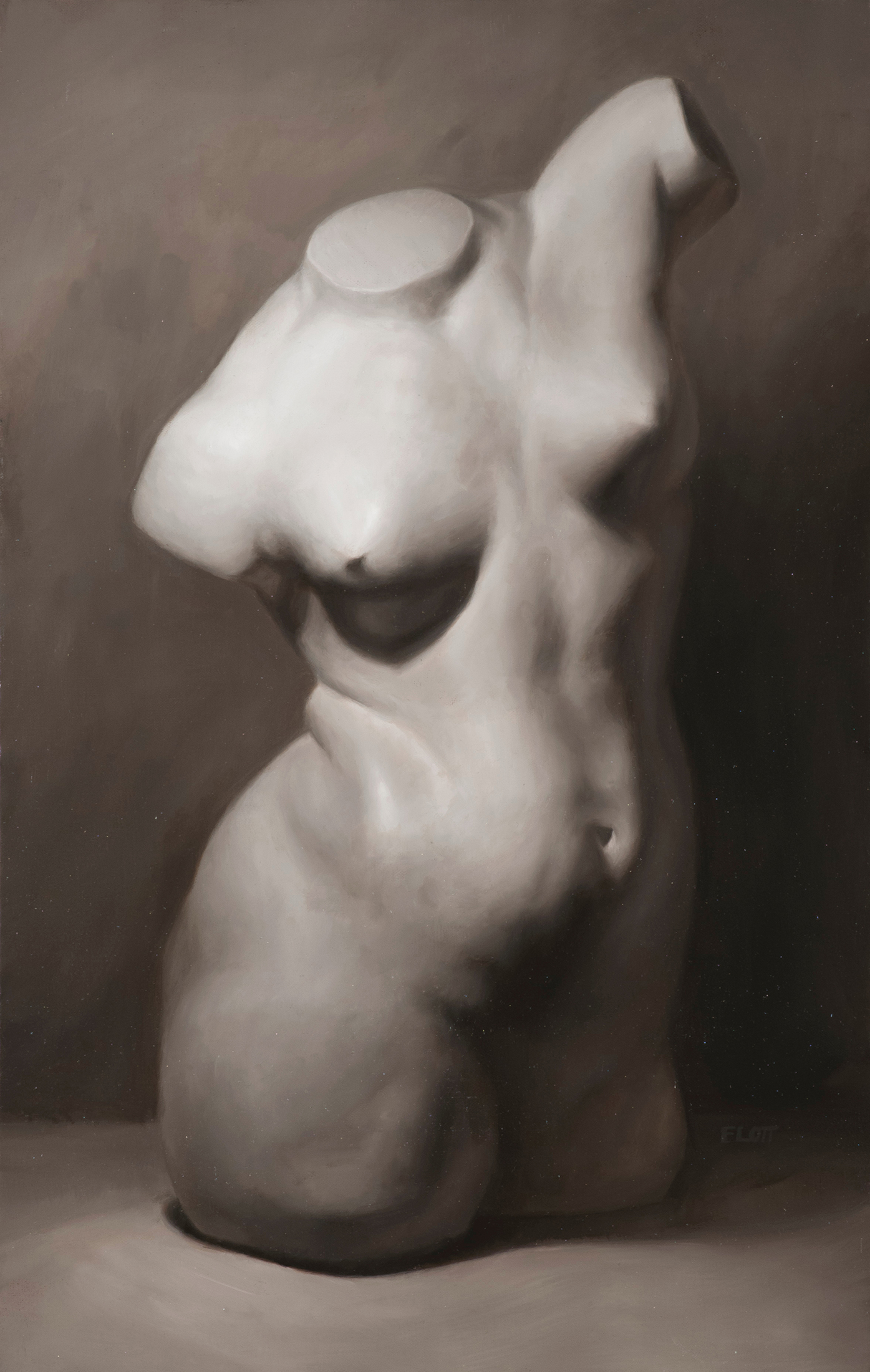

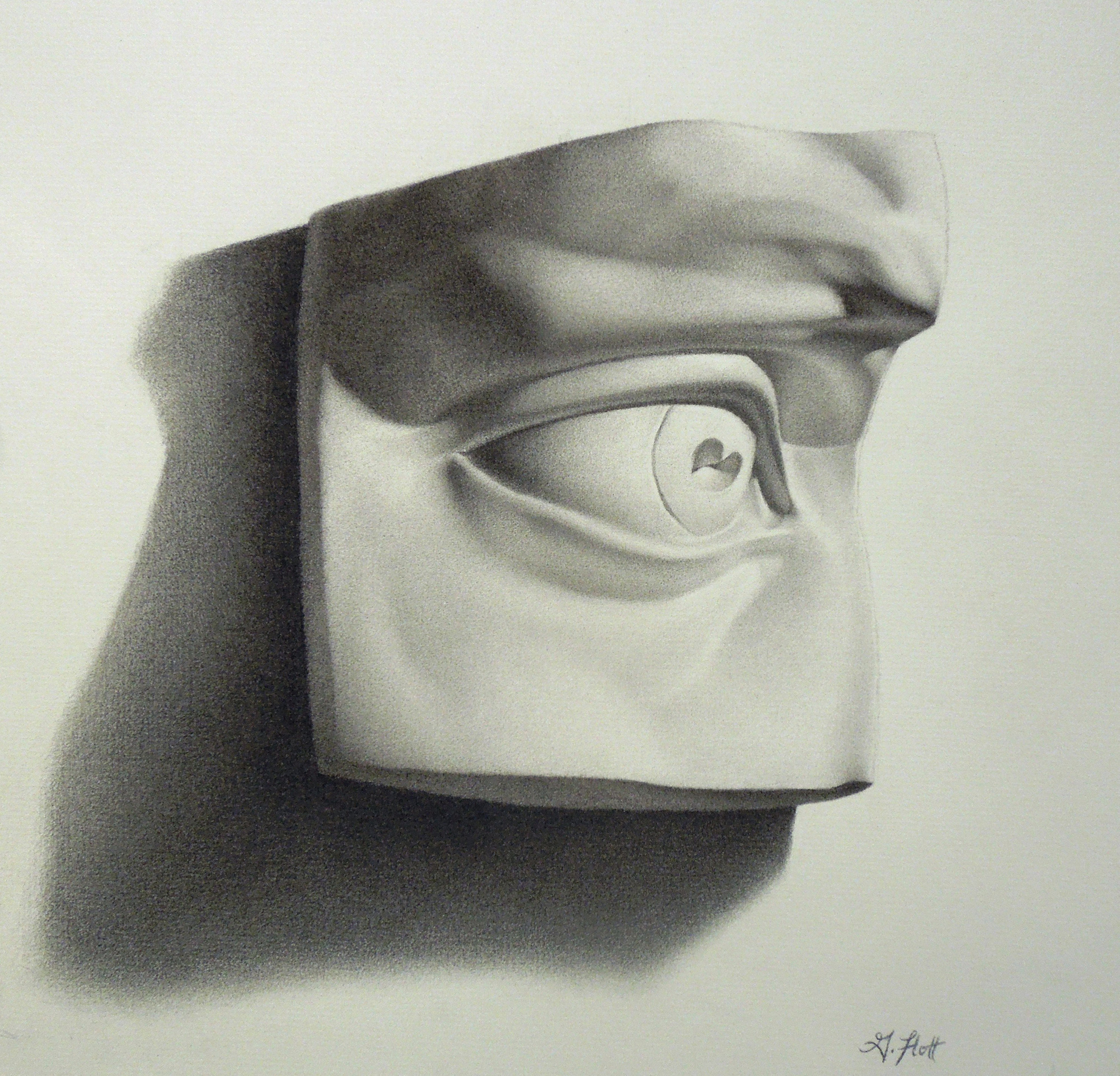

A few of her recent paintings lean against the wall. Most come from an autobiographical series she created for her thesis, which she based on the experience of surviving and rebuilding her body and her life after the fire.

Flott is trained as a representational painter. Realism is her goal. In a self-portrait, the artist holds her palette in one hand, a brush in the other. Her gaze is set straight on, looking for the balance of light and shadows that will capture what she sees. “I wanted the burns to be the focal point,” Flott says. “I wanted the viewer to be confronted with that, and I wanted it to be a point of conversation.

“In our culture there’s not a lot of room to talk about people who exist outside of the norm.”

In April 2011, Flott was 20 years old and nine months into a study-abroad program at Sciences Po (the Paris Institute of Political Studies). She was speaking fluent French, writing 10-page papers in her second language and getting to know students from all over the world. For Flott, who grew up in Spokane, Paris was “very much a dream city.”

Near the end of a late night out, she and her friends stopped at another friend’s tiny apartment in Northeast Paris. Her group was preparing to leave when an explosion ripped through the building. Someone opened the door to the hallway. A backdraft created by an open window sucked in the smoke. “It happened so quickly,” Flott remembers. She couldn’t breathe. She felt unbearable heat on her skin. There was no obvious escape in the unfamiliar building.

“The only thing that was logical to me was to get to the window, but not to jump,” Flott says. “It was to literally breathe one more time before I died.”

She watched another person put their leg over the window sill and fall. She did the same thing, dropping four stories to the ground. “I blacked out on the way down.”

Flott woke in shock and terrible pain with a compression fracture in her lower back, a broken ankle and 50% of her body burned. Her roommate and best friend, Jasmine Jahanshahi, lay dead nearby. Another friend, Louise Brown, also died that day, along with two Swedish students and a firefighter.

After a brief time in a Paris hospital, Flott was flown to Seattle, where she entered Harborview Medical Center for a seven-week stay. That was followed by months of painful recovery at home with her parents in Spokane. She used a walker, crutches and a cane while learning to walk again, and wore compression garments to mitigate scarring from her burns.

Still, she was determined to finish her final year of college as soon as possible. “I just wanted to get back to normal,” Flott says. “I felt like this huge part of myself had been taken away from me and I was really fighting to get it back.” She interned at a Spokane law firm once she could get around without a wheelchair and started classes again at the UW nine months after the fire. She graduated in 2013.

“I was just young enough that I managed to bounce back,” she says. After graduation, Flott worked as a union organizer for health-care workers, continuing the activism she had taken up as a UW student.

While doing better physically, she struggled with depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. She felt distant from her peers—college students and recent grads who mostly agonized about dating, exams and finding jobs. She remembers thinking, “I almost died.”

Making art, a hobby she’d always enjoyed but never seriously pursued, became a lifeline. Painting affirmed her social-justice commitments by offering a medium to elevate unheard voices. It also quieted the voice in her head that told her she would never be safe again. “I realized there was this whole other part of the experience of the fire that I couldn’t put words to.”

Soon she started sketching and taking art classes. At Gage, she learned to apply rigor and an analytical framework to her work. Rather than painting for therapy (“just getting out whatever I felt”), she began to consider what she wanted to say.

Several of her paintings depict medical objects similar to the ones she relied on during her recovery, including a back brace hanging with a pair of crutches, and a wheelchair as still life. Surrounded by these canvasses in her studio, she considers her next project. “I would love to do a longer series around non-normative beauty,” she says. “One thing I really care about is greater visibility for all sorts of bodies.”