If undergraduate education at the University of Washington is so "bad," why does everyone want to come here?

Provost Laurel Wilkening smiles as she is asked the question. Not only do more and more students want to come here, she says, “People want to stay here. They stick around, sometimes too long.”

Against all the anecdotal charges—too many large classes, too much emphasis on research, too many barriers to graduation, an atmosphere that is too impersonal—one solid fact remains: the UW is the number one choice for an undergraduate education in the state of Washington.

“You can take all of the undergraduates at WSU, Western and Evergreen and add them up, and we still have more,” says Fred Campbell, the dean of undergraduate education. “When the citizens of the state ask, ‘Where do we want to send our children?’ it’s here.”

And he might want to add, “… now more than ever.” Last spring, the registrar’s office was flooded with a record number of applications for the freshman class—12,516 for a class that had only 3,626 openings.

Take a look at some other hard facts. If the teaching at the UW is so lacking, why did students last year give it an overall 3.89 rating on a five-point scale? If the crush of classes is so overwhelming, why does the UW retain 90 percent of its freshman class as sophomores?

Scan the winter 1992 survey of UW seniors. When asked if they feel they are meeting their educational goals at the UW, almost 80 percent answer positively, 14.7 percent were neutral and only 5.5 percent gave a negative response. In rating their overall university experience, the seniors responded the same way: 77.8 percent positive, 17.2 percent neutral and only 5 percent negative.

“The University offers students a fabulous education if they take advantage of it.”

William Moody, Zoology professor

A 1990 survey of recent alumni found that three-quarters of the 1989 graduates were employed and another 20 percent continuing their education, a sign that the UW prepares its students for their future vocations and for advanced degrees.

It is facts like these, and a 17 to 1 student/faculty ratio, that prompted Money magazine to name the University of Washington the top public university on its 1993 list of “best buys” in college education.

And the UW has not been standing still. Provost Wilkening has been a champion of undergraduate education since she arrived in 1988. She helped convince the state legislature to put $5.3 million into an undergraduate initiative four years ago, which gave entry-level courses smaller classes, more lab sessions, more emphasis on writing, math-science-composition tutoring centers, and better library and computing facilities.

When the state asked the UW to cut $17 million from its budget a few years later, the money spent on the undergrad initiative was protected. “We got out ahead of some of the problems other schools have had,” Campbell says.

“We’re making very good progress,” adds Wilkening. “Lots of progress was already going on before I came here. Students feel they leave here with a good education.”

But out of the current 25,482 undergraduates, there are critics. One is sophomore Victor Holtcamp. “The education I got in high school beats anything the University has done for me,” he comments. “People aren’t impressed with professors and the way they prepare for their lectures.”

On the opposite side is ASUW Board of Control Member Jeannette Adams. A junior majoring in political science and English, she says her undergrad experience here has been “wonderful.” She is particularly enthusiastic about Freshmen Interest Groups, which she called “the most amazing thing the UW has to offer.”

These groups give incoming freshmen a chance to take all their first quarter classes together, plus meet once a week with an older student adviser to learn study skills. The groups are organized by interests, such as pre-med, pre-law, literature or environmental sciences.

The popular groups provide an instant network. Senior Christopher Famy says his interest group helped forge long-term friendships, including his current roommate. One of his fondest moments came when his group met its Psychology 101 professor for pizza at Godfather’s. “We were able to learn from each other, to gain from each other’s abilities,” he recalls.

Famy and Adams praise their education, but add it could be even better. Adams, a junior, also serves as the student representative on the Faculty Council on Academic Standards. In this position, she’s often heard student complaints. “There are problems and a lot of room for improvement,” she reports, such as limited access to high-demand classes and too many graduation requirements.

Some faculty also see problems. English Professor Sally Mussetter says, “I really don’t think the kids, by and large, get their money’s worth. People can go through the program and never have a full professor.” It’s partially a case of ineffective teaching, partially the fault of huge classes and partially the problems inherent in an urban, commuter campus, she asserts.

But Zoology Professor William Moody, winner of a UW Distinguished Teaching Award, responds, “The University offers students a fabulous education if they take advantage of it. I don’t think it’s true that a student could go through here without being taught by excellent faculty members.” As for students getting their money’s worth, “compared to other universities, this place is a bargain,” he notes.

“We got out ahead of some of the problems other schools have had,” says Undergraduate Dean Fred Campbell.

Undergraduate Dean Campbell is proud of the UW’s undergraduate program, yet knows that some students are dissatisfied. No one, he notes, can guarantee that 100 percent of the student body is going to be pleased, no matter what university they attend.

But, he adds, no undergraduate program is 100 percent perfect, either. “It takes too long to graduate, yes, I can agree with that,” says Campbell. Tell him there are too many large classes, and his head nods in agreement. Say that the education may not be relevant to the 21st century, and you’ll find no disputes.

Of the problems undergraduate education faces at the UW, slow graduation rates most trouble Campbell and Wilkening. It’s a problem that all urban, commuter campuses face. For example, of the UW freshmen who began their studies in 1983, only 48 percent had earned their degrees five years later. At some peer institutions, those same 1983 freshmen graduated at much faster five-year rates: 77 percent at Michigan, 75 percent at North Carolina, 74 percent at Illinois, and 59 percent at Wisconsin and UCLA. Other peer schools had lower rates, such as Oregon’s 38 percent and Arizona’s 37 percent. It is important to point out, says Campbell, that the schools with the highest rates—Michigan, North Carolina and Illinois—do not allow undergraduates to enroll on a part-time status.

The UW’s five-year graduation rate is improving and was at 53 percent for freshmen entering in 1985. Campbell says it is unreasonable to expect the UW to match schools that only enroll full-time students. He’d like to see the UW rate in the “high 50s.”

“It’s not that simple,” to increase the rate, says Provost Wilkening. “More than 70 percent of our students work,” she notes, and as the working hours have increased over the decade, there has been a drop in the course load taken each quarter.

“Students feel they leave here with a good education,” says Provost Laurel Wilkening.

“Some people just don’t want to leave,” she adds, which slows clown the pace. Students go on for a double major, thinking they’ll be more attractive in the job market. Many students are in no rush to face a recession and bleak hiring climate; others just want to enjoy the intellectual opportunities as long as they can, the provost says.

Another barrier to graduation is the general degree requirements each student must meet. “The undergraduate curriculum has become ossified,” Wilkening concedes. “There is too much clogging up.”

The requirements for an arts and sciences undergraduate can be confusing, says Director of Academic Counseling Richard Simkins. For example, students must get a breadth of knowledge by taking a minimum of 20 credits each in humanities, social sciences and natural sciences. Simple enough, until you add the qualifier that some of these credits must come from a two-course “linked set” of classes. For example, every student must take a linked set in natural sciences, such as Oceanography 101 followed by Oceanography 102.

Suppose you’re a freshman who took “Ocean 101” and now wants into “Ocean 102.” Every quarter you try to enroll, but the course is closed. It’s jammed with juniors and seniors who are trying to get their last requirements out of the way. You can start over on another “linked set,” or you can take your chances that sometime in the future you can get in.

To improve the graduation pace, Undergraduate Dean Campbell is trying to initiate “guaranteed enrollments,” where if you start a sequence, such as French 101, you are guaranteed enrollment in French 102 and 103 in the subsequent quarters.

The number of general education courses also appears to be shrinking. “As requirements have become more complex, we’ve had fewer courses offered,” Counseling Director Simkins says. “There has been a gradual decline in the number of general education courses.”

“Availability of classes is the number one problem in undergraduate education,” says ASUW Member Adams. She feels too many professors only want to teach upper-level courses and that there should be some type of “mandate” to force professors to teach at lower levels.

English Professor Mussetter sees the access problem every day in her overloaded classes. She often teaches “W” courses, classes that emphasize writing skills. Arts and sciences students need 10 W credits to graduate.

“Every time I teach a W course, I have to turn people away,” she laments.

Last quarter she turned away 23 students, many who said they were seniors and needed the course to graduate. When an opening comes up, she holds her version of the Washington State Lottery. Students on the waiting list pick a slip of paper out of an envelope. If they are “lucky dawgs,” the right number comes up and they may graduate in time. “I feel awful,” Mussetter says about the process.

“What we have now is not a cohesive, smooth flowing system. I'd like to make it easier for a student to pass through.”

Christopher Famy, UW senior

Streamlining these requirements could help unclog classes. A task force headed by Zoology Professor Moody is looking at an overhaul of the general education requirements for the College of Arts and Sciences. A faculty senate council is also rewriting graduation requirements for the entire University. The results are not due until the end of the school year, but the panels may follow earlier proposals that would scrap linked sets, integrate the math/logic/statistics requirement into the major, weave writing requirements into the major, and offer minors.

Senior Christopher Famy, who is a student representative on the task force, is looking for more “freedom of choice.” He wonders, for example, why some English classes can fulfill a humanities requirement, while others cannot. “It seems to be pretty arbitrary to me,” he comments. “What we have now is not a cohesive, smooth flowing system. I’d like to make it easier for a student to pass through.”

When a student passes through and gets a degree, Moody feels, “a student should be able to think critically. As one colleague told me, a graduate should be able to control information rather than being controlled by it.”

Moody’s words fit well with Provost Wilkening’s overall vision of what an undergraduate education should be. “College is about making the next step of intellectual development. You don’t just describe, you have to apply knowledge and make judgments. You have to rationalize or advocate those judgments.” Isn’t that what alumni do on the job every day, she asks, whether they are scientists, salespeople, lawyers or doctors.

But there is only so much the UW can do internally. That’s why there is a $13.8 million request in Olympia to enhance undergraduate education, the UW’s number one priority. In his parting budget, former Gov. Booth Gardner suggested funding $8.6 million of that amount. The new money would buy:

At the top of the list are improvements in the large lecture courses that face freshmen and sophomores.

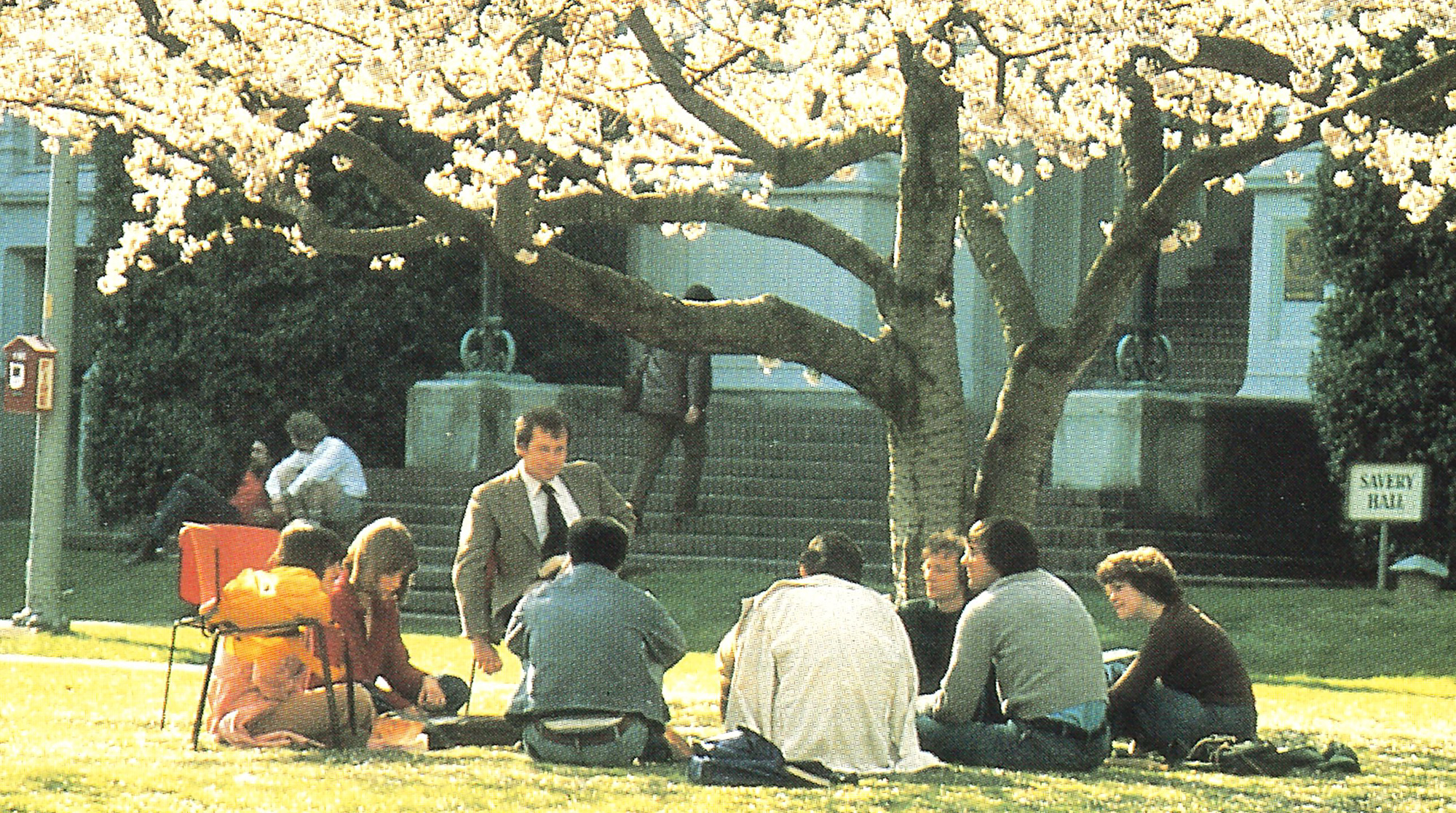

“There will always be large classes here, but there are too many large classes,” Undergraduate Dean Campbell concedes. Large classes come in three flavors, he adds. Some are large because the students want the professor, such as Giovanni Costigan’s popular history classes of the past or today’s offerings by Historian Jon Bridgman and Sociologist George Bridges.

Then there are classes that must be large because of the material and the demand. For example, the introductory chemistry series is crucial to science majors, premed and engineering students.

These large classes are improving, says Campbell. Before the UW’s undergraduate initiative, introductory physics didn’t even have lab sections, now it does. Decreasing the class size for these courses isn’t practical, he adds, so Campbell wants to increase the number and quality of the TAs.

Then there are the classes that shouldn’t be large, such as basic math and precalculus courses. “It’s a continuing problem and it’s true all over the country,” says the undergrad dean. “Much of it is what they are supposed to have taken in high school.”

One department trying to reduce class size is English. Starting in the fall of 1993, all English majors must take a senior seminar limited to 15 students and taught by professorial faculty, says English Chair Thomas Lockwood. “We look upon this as a significant program improvement,” he says.

English has been flooded with majors ever since the UW tightened its policy on declaring a major. Ten years ago there were about 500 to 700 majors, Lockwood says. Today there are between 800 and 1,000. Over the same period, he notes, the department has lost about the equivalent of five full-time faculty positions.

Due to enrollment pressures, Lockwood says the, department has considered expanding some 200- and 300- level courses, making them lectures with smaller discussion sections taught by TAs. “We have no plans to do that at the present,” he says.

While English Professor Mussetter applauds smaller classes for majors, she is worried about the possible move toward some large lectures. “I am having a hard time with that,” she says. “Good undergraduates shouldn’t be taught by people who are two years ahead of them in school.”

A lecture system turns students into “passive receptacles,” she continues. “In the humanities ideally we are not telling them what to think, we are showing them how to think.”

While everyone agrees smaller classes are beneficial, there is a debate—common to most large universities—on the amount of emphasis that should be placed on research. Some professors, says ASUW’s Adams, “don’t seem to care as much. They are in it for the research, not the teaching.”

But the UW’s research faculty was one of the draws for fellow student Famy. “I was attracted to the research potential here,” he says. The pre-med major was not disappointed and says it has been “a top-line education.”

“Asking what is more important, research or teaching, is like asking a child who do you love more, your mother or your father? It’s the wrong question,” says Campbell. Instead, he says we should ask “how excellent” each effort is, and make sure the UW excels in both.

“To achieve excellence in teaching, we have to honor it and reward it,” Campbell adds. “Faculty have to honor one another for the work that goes on in the classroom. And we have to build into that reward merit pay, advancement and tenure.”

Wilkening says that tenure reviews are emphasizing teaching more and more. On some occasions, she has told a dean that she will not approve tenure “unless you come up with a plan to improve the candidate’s teaching,” And, she adds, “the junior faculty have gotten the word,” and are using UW resources, such as the Center for Instructional Development, to improve their presence in the classroom.

Meanwhile, more attention is being paid to undergraduate education beyond the campus boundaries. UW Government Relations Director Bob Edie reports that the new legislature has a keen interest in fostering improvements. And the UW Alumni Association has made improvements in undergraduate education one of its top priorities, with UWM Board Member Lawrence Matsuda heading an undergraduate education committee that welcomes alumni input.

The University of Washington will never be the perfect place for every student to attain a bachelor’s degree. That’s one reason the state system has a diversity of college experiences, from the experimental atmosphere of Evergreen to the medium-size schools like Western Washington to the full-scale research institutions like the UW and WSU.

“If you are willing to take what the professor is willing to give, you can get an incredible education here,” says Junior Jeannette Adams. “To get the best quality, education, you have to pursue it actively,” adds Famy.

“You have to reach out to the instructor and teacher.” If you do, he says, you’ll discover that “we have one of the best schools on the West Coast.”