Its natural setting has few equals. In the distance are two mountain ranges, at its boundaries two bodies of water, at its focal point a priceless view of a 14,411-foot volcano. Yet the University of Washington campus is also a treasure thanks to the planners, architects and gardeners who took logged-over land and made it into a garden of delights. For those who can't come back often, or who may have missed some newer campus beauty spots, the editors of Columns showcase 10 of their favorite UW outdoor settings.

***

Rainier Vista

On a crisp winter day when the skies dry out and the sun sets early, Mount Rainier turns into a pink pyramid floating over the city of Seattle. It is dusk, what Hollywood cinematographers call the “magic hour,” and it is indeed magic if you linger on the steps leading from “Red Square” to Rainier Vista.

Before you hovers a 14,411-foot mass of snow and rock, and the rare clarity of the air makes it seem as if you could reach out and touch a glacier. Almost any time the mountain is “out” is a signature moment in the lives of students, faculty and staff at the UW.

The view is without doubt the natural icon of the University of Washington—the image burned into our brains that we will never forget. It wasn’t always going to be this way. John C. Olmsted, commissioned to draw up a campus plan in 1904, may not have seen the mountain during his first visit. His original scheme, a jumble of academic buildings, lacked any Rainier Vista.

But chance favored the UW. When Olmsted returned to draw plans for a 1909 exposition held on our campus, the mountain may have been out. This time Olmsted saw the potential of a grand promenade with Mount Rainier as its focal point. His idea became the center point of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition and has remained through every turn of campus development.

Almost a century later, we still have the same excitement, and the same view, that he did when he created Rainier Vista.—Tom Griffin

***

Burke-Gilman Trail

We cyclists, walkers, joggers, runners, roller-bladers and outdoors lovers owe a huge debt of gratitude to Judge Thomas Burke and the 10 other investors, who, in 1885, got together to establish a Seattle-based railroad so that the young Emerald City could become a major transportation center. While their effort ultimately didn’t pan out the way they had planned—it was supposed to connect Seattle with Canada’s transcontinental rail line—it did yield one of Seattle’s best places: the Burke-Gilman Trail.

In 1971, the railroad line, which reached Arlington and served the Western Washington logging industry, was abandoned. But citizens quickly realized what great potential the trail had for non-motorized transportation and launched a movement to acquire the right of way for a public biking and walking trail. After overcoming the objections of residents living near the proposed trail, the City of Seattle, University of Washington and King County cooperated in developing the route.

In 1978, the Burke-Gilman Trail opened with a 12.1-mile path that connected Gas Works Park and King County’s Tracy Owen Station in Kenmore. Today, the trail—which cuts through some prime UW territory parallel to Montlake Boulevard N.E.—remains a booming success. Just see how crowded it gets on weekends or just before school starts each morning. There are no more locomotives, but we still love to chug along the trail.—Jon Marmor

***

Liberal Arts Quadrangle

Visiting the “Quad” in the spring is a spiritual experience. While Rainier Vista may be the UW’s natural icon, the Quad is its natural sanctuary. Walking through the rows of 30 Yoshino cherry trees in bloom, you can’t help feeling uplifted, transported.

But it doesn’t have to be the last weeks of March or the first weeks of April for the Quad to work its magic. Summer promises deep shade and sudden sunshine; the fall offers crimson leaves and crisp vistas. Any time of year you have the ornate Collegiate Gothic architecture, inspired by the classic quadrangles of Oxford and Cambridge, offering food for the eye and for the soul.

There are many we can thank for the Quad: Carl Gould’s 1915 campus plan and his insistence on one architectural standard for its buildings; Henry Suzzallo’s determination to fund its buildings; Charles Odegaard, Fred Mann and Eric Hoyte for putting the cherry trees into its rather empty center. Did any of them know how successful it would be? Sadly, the trees are aging—as are the buildings. Now it is our turn to preserve what they accomplished.—Tom Griffin

***

Memorial Way

Memorial Way—the University’s ceremonial entrance to campus from N.E. 45th Street—is an outdoor cathedral. The London Plane (sycamore) trees planted on Armistice Day, 1920, to honor the 58 UW alumni, students and faculty, (57 men, one woman) who died during World War I form a gorgeous, haunting canopy. (Although 58 were planted in 1920, today 101 trees grow along the one-quarter-mile segment of Memorial Way from N.E. 45th Street to the campus flagpole.)

Memorial Way—the University’s ceremonial entrance to campus from N.E. 45th Street—is an outdoor cathedral. The London Plane (sycamore) trees planted on Armistice Day, 1920, to honor the 58 UW alumni, students and faculty, (57 men, one woman) who died during World War I form a gorgeous, haunting canopy. (Although 58 were planted in 1920, today 101 trees grow along the one-quarter-mile segment of Memorial Way from N.E. 45th Street to the campus flagpole.)

The entrance to the street, while not enveloped by the trees, is framed by two stone pylons that were placed there in 1928. They carry plaques with the names of University people who lost their lives in World War I. The plaques are kept as alive as the trees, as one local fraternity requires its pledges to polish the names of its listed brothers to this very day.

But it is the trees that really transport you, no matter the season. You can lose yourself as you walk down the sidewalk under the droopy branches toward the heart of campus. Emerging at the open space surrounding the main campus flagpole, you know you have just been someplace special.—Jon Marmor

***

Husky Stadium

Every time I walk or drive by Husky Stadium, I have to look … I just have to. Sports stadiums always have been magnets for my attention, especially those with the history and grandeur of the home of the Dawgs.

For one thing, the setting is mesmerizing, with its signature view of Lake Washington and Mount Rainier from the north stands. But there’s much more to it than the eye-catching appeal of the place, the cantilevered roofs and the oversized, corkscrew, concrete walkways. For this, as we all know, is a cathedral of football excellence, where the Huskies routinely run roughshod over their opponents (winning 61 of their past 70 games there and going 326-133-21 since play in Husky Stadium started in 1920 with a rare home loss to Dartmouth, of all teams).

The stadium—routinely voted the most scenic football structure in the nation—is also an ear doctor’s dream. The 72,500 fans (it is always full) create enough noise to not only make it impossible for the Huskies’ opponents to hear themselves think—but also inflict pain and suffering on any and all eardrums inside the stadium. (In fact, the audible mayhem once was clocked at a headache-inducing 135 decibels in one ESPN measurement.)

And why not? The memorable games and players that made their mark on Husky Stadium—from George Wilson to Hugh McElhenny to Steve Emtman to Marques Tuiasosopo—have left behind a loud legacy.—Jon Marmor

***

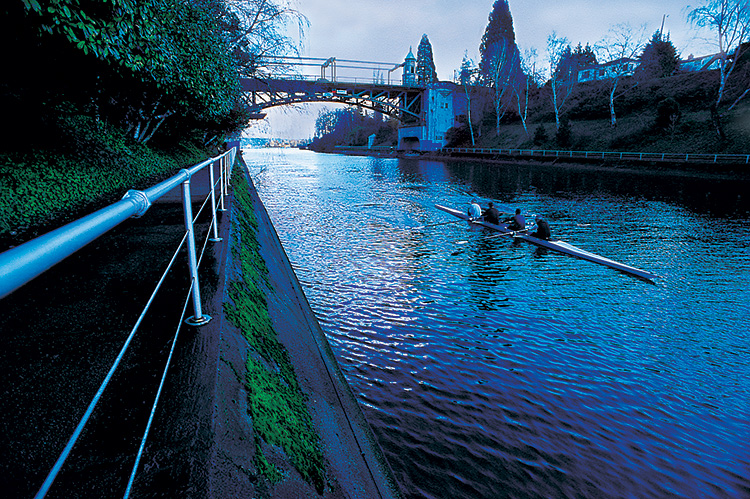

Lake Washington Ship Canal

Head behind the cluster of small brick buildings to the south of the massive UW Medical Center and you will find yourself in a piece of campus paradise—the Lake Washington Ship Canal Pathway.

The canal itself was completed in 1917, and today the Montlake Bridge and “the cut” (another name for that portion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal) are historical landmarks. What the pathway offers is waterfront real estate that is lush, green and quiet. Much of it used to make up the long-gone but much beloved University Golf Course (now home to the health sciences complex).

Take a close look at the open spaces between the rows of trees and you can easily make out that you are standing on what used to be a golf course. The course winds under the Montlake Bridge and behind Husky Stadium, offering a wonderful place for runners, walkers and those of us who just want to take a moment to enjoy the fresh air, watching the geese and ducks along the shimmering water.—Jon Marmor

***

Grieg Garden

The Grieg Garden is the reverse of what folksinger Joni Mitchell once sang about—they “unpaved” a parking lot and put up Paradise.

The Grieg Garden is the reverse of what folksinger Joni Mitchell once sang about—they “unpaved” a parking lot and put up Paradise.

Until the renovation of the HUB Yard in 1990, the space south of Thompson Hall was for cars. Today it is for people (and squirrels). One of the UW’s newest beauty spots, the Grieg Garden is a cozy clearing surrounded by trees and flowering shrubs. Located on the north side of the HUB Yard, it is best in the spring, when rhododendrons and azaleas frame the space in drifts of lavender, crimson, magenta and pink. On its teak benches—right out of a Smith and Hawken catalog—you will often find young couples holding hands or harried graduate students taking a break from the library.

Dominating it all is a bronze bust of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg. Originally cast for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, a group of Scandinavian fraternal societies gave the sculpture to the UW in 1917. For many years he rested in front of the old Meany Hall; later he was placed in the HUB Yard. Today he is the centerpiece of this garden, but he has a mystery surrounding him. Grieg’s nose lacks the patina on the rest of the statue—it is ever shining. Could it be true that one fraternity requires its members to polish the nose as a rite of passage?—Tom Griffin

***

Medicinal Herb Garden

The largest medicinal herb garden in the Western Hemisphere sits on three hectares of land south of Bagley Hall and the new Chemistry Building, but some faculty and students don’t even know it’s there. They hurry between South Campus and Frosh Pond, missing the scents and sights of more than 500 medicinal herbs.

The largest medicinal herb garden in the Western Hemisphere sits on three hectares of land south of Bagley Hall and the new Chemistry Building, but some faculty and students don’t even know it’s there. They hurry between South Campus and Frosh Pond, missing the scents and sights of more than 500 medicinal herbs.

The range is astonishing. In addition to the old standards of rosemary, fennel and laurel, you can find prickly pear, wild tobacco and even wormwood. The garden design is minimal—rectangles of raised beds surrounded by gravel pathways—but when I go there on a summer’s day, I feel transported to Provence or Padua.

That others aren’t similarly impressed is no surprise. For many years this campus treasure has suffered from benign neglect. Started by the School of Pharmacy in 1911, in its heyday the garden had 836 species on eight acres. But after World War II synthetic medicine took the place of natural plant extracts. Hit by severe budget cuts, the School of Pharmacy stopped all funding in 1979.

The garden might have been lost, but faculty in the Department of Botany saved it. Staffing was limited and the garden suffered until a group of volunteers—Friends of the Medicinal Herb Garden—began to restore the beds in 1984.

Another threat came with the construction of the Chemistry Building in 1992 (one UW administrator wanted to turn it into a parking lot). But concerned faculty, staff and volunteers secured some of the construction money to move and renovate some of the beds. About three years ago things started looking up: Keith Possee was hired as its gardener, and he’s maintained the plants and added to the collection. The result—the gardens look better today than they have for 20 years.—Tom Griffin

***

Union Bay Natural Area

Once part of the city’s old Montlake garbage dump, the Union Bay Natural Area is now an oasis, one I try to escape to as often as I can.

Hugging the shore of Lake Washington just northeast of Husky Stadium, and running behind the Center for Urban Horticulture, the 55-acre wildlife area is an important place for students and faculty to conduct research in ecology, zoology, biology, engineering, landscape architecture, botany and more. But on a more basic level, it’s a fabulous place to walk your dog, enjoy one of the area’s premier bird-watching spots, and just disappear from the hubbub of city life (even though you could probably hit the University Village Shopping Center with a good Frisbee throw).

It’s long been Seattle’s best urban bird-watching site, with more than 180 migratory and resident bird species recorded and new sightings occurring every year. The area (which served as a city dump from 1926-66 but was morphed into a natural area beginning in 1972) is also home to raccoons, opossums and skunks among other creatures (and had been the site of zillions of wild blackberry plants, which provided great eats but are now being eradicated because of the threat they are causing to the area’s other flora).

Now under the careful watch of the Center for Urban Horticulture, the Union Bay Natural Area is closely managed to maintain and enhance the vegetation, wildlife and landscape values while serving as an outdoor laboratory for research, teaching and public service. And getting away from it all.—Jon Marmor

***

Sylvan Theater and Columns

It took me years to discover the columns on campus. I had heard they were “somewhere” near the Electrical Engineering Building, but I didn’t have much interest in searching for them. So I often trudged by a wooded yard, not knowing of the delights waiting just a few feet away.

It took me years to discover the columns on campus. I had heard they were “somewhere” near the Electrical Engineering Building, but I didn’t have much interest in searching for them. So I often trudged by a wooded yard, not knowing of the delights waiting just a few feet away.

When, on a summer’s day, I finally stumbled upon the clearing that is the Sylvan Theater, I was astonished. How could this delightful spot be hidden away so easily? Soft, lush grass led to a natural platform with four Ionic columns, starkly white against the green background of fir trees.

I couldn’t help but stand for a moment on the platform and look down on the empty clearing. Then I touched a column and thought back to the founders of this university—working quickly in 1861 to put up a building and start classes before the next session of the territorial legislature. How, in their haste, had they found the time to hand-carve the fluting of these four columns out of Western cedar?

I thought about alumni from 47 years later, trying to save the original building from the wrecker’s ball and ending up with just these four columns. History Professor Edmond Meany and Dean Herbert T. Condon dubbed the pillars “Loyalty,” “Industry,” “Faith” and “Efficiency,” the first letters spelling “LIFE.” But to me they symbolize the dreams and aspirations of this university from 1861 to the present—that out of the wilderness would rise a great seat of learning, and that, like the original columns, it would be preserved for future generations.—Tom Griffin