Returning to Vietnam was not on Rich Kirchner’s bucket list. He survived his service in the Vietnam War 42 years earlier and, for the following decades, did not see what good could come from paying history another visit. There was no homecoming to be had. Yet, in June 2013, he found himself again disembarking from a helicopter onto a grassy hilltop in north-central Vietnam. He was part of a Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) expedition to locate the remains of two soldiers killed in 1972. It was a mission worthy of his returning for those who never left.

“When I was in the service, one thing we believed was that no one would be left behind. No matter what, if you should survive in any form, we will come back for you,” says Kirchner, a Bay Area architect. “I think that extends to those who died. Standing on that hill, I had a visceral conviction that it’s true.” The Shau Valley stretched before him. Everything was the same yet transformed. The heat remained stifling at 105 degrees. The outline of the mountainous landscape was identical, but now populated by cows. Their grazing left the green grass perfectly manicured, closer to a golf course than a battlefield.

Bruce Crosby Jr.

“I looked at the hill and kind of lost my breath,” says Kirchner, 69. “There it was, the same as before, but totally different.”

A 1968 graduate from the UW’s College of Built Environments, Kirchner used his architectural expertise as a first lieutenant in the 27th Combat Engineer Battalion to design everything from roads to bridges. But one project haunted him—a bunker he designed that once stood on the site he revisited, previously known as Fire Support Base (FSB) Sarge. During the 1972 Easter Offensive, enemy shellfire destroyed the structure, which reportedly burned for two days.

Gary Westcott

The explosion and fire killed two 20-year-old Army soldiers, Sergeant Gary Westcott and Specialist Bruce Crosby. Their remains were never recovered. Kirchner did not know them personally, but is connected through time and place. His firsthand knowledge of the site and the structure might be the breakthrough needed to locate them and bring them home.

“It’s been a thorn in my side. I wanted to fix this,” says Kirchner. “I wanted to help connect the dots and possibly affect a recovery operation.”

Until they are home

JPAC’s mission is to search, recover and identify the remains of soldiers from World War II as well as the Korean, Vietnam and Cold Wars. It is a U.S. Department of Defense joint-task force of nearly 500 military personnel representing all branches of the Armed Forces, civilian contractors and occasionally selected volunteers such as Kirchner. JPAC was founded in 2003, but efforts to locate missing Vietnam soldiers began as early as 1973 and didn’t really kick in until the mid-’80s when relations with Vietnam began to improve.

JPAC’s motto is “Until They Are Home,” but it is a call to action to people like Kirchner. He was discharged in March 1972, three weeks before the deadly Easter Offensive attack. He returned stateside unaware that the bunker and its personnel had perished. He bought a new 1972 Camaro and drove Route 66, visiting friends and family before job opportunities enticed him to Albuquerque, N.M. There, he launched his career as a civilian architect and he crossed paths with a fellow soldier who informed him of FSB Sarge’s fate.

“As a junior officer, I took responsibility seriously. I didn’t lose anybody while I was in Vietnam, but this subsequent revelation bothered me,” Kirchner recalls. “The invasion of 1972 was an all-out offensive backed by tanks and long-range artillery. Soldiers died in that bunker I designed. It gnawed at me.”

A future deferred

Rich Kirchner was like many of his college peers. he was a fan of the Beatles and Star Trek, attended Husky football games and was a fraternity member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon. His group of friends was nicknamed “The Bellevue Boys,” from where he attended high school. Unlike every generation, though, his college experience was also marked by unrest and upheaval. He remembers seeing rows of police cars lined up behind the UW Administration Building the day it was taken over by protesters in 1968.

“In ’68, there were the assassinations (Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.), war protests, the Chicago riots and Nixon’s election,” says Kirchner. “I was very aware of what was going on, but it also often felt like it happened on the periphery. I didn’t have much time for anything else but school.”

Being a student at the UW put him one step closer to his longtime dream of becoming an architect. A student of the College of Built Environments, he needed to complete five years of study, and that required concentrated studying. By the summer of 1968, he only needed one elective class to graduate. He took a course in Scandinavian literature—weeks of Søren Kierkegaard—which he couldn’t stand.

“On the last day of summer school, I threw the book into the trees, happy with a barely passing grade, jumped in my ’66 Mustang and never looked back,” laughs Kirchner.

He was excited to join the ranks of the world outside of campus. However, like many young men of the era, he was drafted by the military. His first notice arrived during his fourth year at the UW. But he chose to enlist instead since doing so offered him more options. After basic training, he entered the prestigious Engineer Officer Candidate School at Fort Belvoir, Va., and received his commission on Halloween 1969. Thanks to his architectural background, he was assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers District in Albuquerque. He spent two years there, even playing on the state championship-winning softball team.

In August 1971, he received his orders for Vietnam. He was given two months to arrange his affairs, say his goodbyes, pack up his life, designate next of kin and make a will.

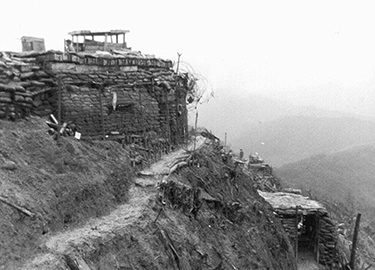

Fire Support Base Sarge, 1971

Realities of war

The C-130 cargo plane flew farther and farther north toward the DMZ—the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone between South and North Vietnam—and a combat hotspot. The plane dove toward a dirt airfield, touched down and immediately spun round for takeoff. The door dropped open and Kirchner and a fellow soldier rolled out in a tumble of duffle bags and brand new jungle fatigues. The C-130 then took off in a thunderous departure. The blowing dust was their only cover; they were exposed in the middle of nowhere.

“We felt pretty naked standing there waiting for someone, anyone to pick us up, quickly. That’s when you realize things had gotten serious,” says Kirchner. He was stationed at the well-fortified Camp Eagle. However, he was frequently required to survey remote areas as the reconnaissance officer for the 27th Engineers. “By late 1971, things got quiet because we were pulling troops out. Transferring the war effort to South Vietnam was in full swing. I think the enemy was smart enough not to waste a lot of manpower and ordnance on a retreating foe. They were going to wait until more soldiers withdrew and then attack those left behind,” recalls Kirchner. “I was flying around thinking to myself, was this just the lull before the storm?”

He was tasked to oversee the design and installation of the FSB Sarge bunker, all of which was to be airlifted into the site, practically overnight. At the time, what it would house was top secret. Decades later, Kirchner learned it was communications equipment used by the Army Security Agency (ASA), a part of military intelligence.

His last visit in December 1971 proved fateful. For the first time, he packed his Instamatic camera so he could take photos to show his parents. He snapped four pictures of the completed bunker and surrounding landscape. They were his only recorded images from that time. Little did he know how pivotal they would become decades later. Minutes after he shot his last photo, he realized the Huey helicopter was soon to arrive to pick him up. He scrambled to the top of the hill. The pilot hovered rather than landing due to the threat of enemy fire. Kirchner jumped from a cliffhanging bunker’s roof to the Huey’s fixed landing skid —barely making it—as two soldiers pulled him inside and the helicopter peeled away. “It really was a leap of faith. It’s crazy the things you do when you’re young and think you’re immortal,” says Kirchner.

The lower hill at Fire Support Base Sarge in 1971 and 2013.

Reaching forward into the past

After he returned stateside, life marched forward. He moved to California, started his own architectural firm and eventually merged with another firm to become a major presence in the profession. He married, had a family and attended as many Husky football games as possible. Occasionally, Westcott and Crosby crossed his mind—those two lives curtailed at 20 years of age, unable to experience life’s full arc. “At the time, I would look around and basically see a bunch of kids (I was 26). Some of them hadn’t even learned to tie a tie yet,” says Kirchner. “Gary (Westcott) married his sweetheart only about three weeks before he was killed. Tragic.” After the advent of the Internet, Kirchner went online one day and searched for FSB Sarge just out of curiosity. He didn’t expect to find anything. He was wrong.

“Holy cow!” he recalls saying. “There were all kinds of postings and photos, including one of the hill. I dug through my old books and I had almost the same exact photo.”

FSB Sarge was already on the joint-task force’s list of recovery locations. Kirchner began corresponding and sending photos and maps to aid the group’s efforts. But it was a challenging mission. The original bunker was only 10 feet x 16 feet. Most metal fragments were long ago scavenged and bartered by locals for food. After two search teams who went to Vietnam failed to find evidence of the bunker, Kirchner was invited to assist—in person. The last call.

“My wife says I didn’t even hesitate when asked,” says Kirchner. “There was a loose thread that needed to be tied up and I was just happy to help.” On Memorial Day 2013, he found himself in Hawaii readying for his flight to Hanoi. The expedition was a mix of 12 people ranging from anthropologists to military personnel, linguists and a fellow Vietnam veteran.

With their help and using his iPad, Kirchner flipped between the current landscape and his 1971 photos. Through hilltop alignment and comparison, the team was finally able to pinpoint the exact location of the bunker. If timing and funding allow, the next step will be to dispatch a recovery team that will conduct an archaeological dig. The explosion and subsequent fire incinerated the bunker, but if even bone fragments are found, it will be enough to conclusively lay to rest the memories of Westcott and Crosby.

Looking for answers in the right places

The hilltop vista was breathtaking. the sky was a blank canvas of blue, unspoiled by the sight and noise of Huey helicopters. It was peaceful due to the lack of nearby roads or bellowing of artillery. The scenery was green as far as the eye could see—trees and grass rather than red clay and deforestation.

Kirchner’s group spent five hours on the hill and lunched with local farmers who brought a knotted plastic bag filled with homemade soup and chicken. Throughout his visit, the Vietnamese people were welcoming and without animosity. He even met a Vietnamese soldier of his age whose observation was simply, “We’re all in the same foxhole now.”

“The trip was really a healing adventure and I’m very glad to have participated. The new Vietnam is nothing like the old Vietnam we served in. There is little reminder of what was,” says Kirchner.

The Vietnam Kirchner saw through his camera lens 40 years ago was not reduced to a tourist’s souvenir. It was the landscape of memory. Kirchner paid respects to the lives lost, redirected and forever changed. Even for those who will never physically return, the recovery effort itself is a hopeful homecoming for human nature.

“I’m probably more interested in this quest as a father than as a former soldier,” says Kirchner. “If something similar happened to my son, I would want somebody like me to care enough about him to see the journey through no matter—even 40 years later.”