A democratic society needs a professional intelligence service, staffed by liberal-arts educated individuals of integrity and imagination, and that the study of intelligence as an enterprise is important to military, diplomatic and political history.

—Yale historian Robin Winks

When W. Stull Holt arrived in Seattle in the fall of 1940 to start his new job as the chairman of the University of Washington history department, the university was thrilled to have a rising faculty star to modernize the department. But the UW was getting much more than a proven scholar and teacher in Holt, who was recruited here from Johns Hopkins University. The New York City native—who went on to teach at the UW for nearly three decades—embodied a concept I call the “Warrior Intellectual.” That refers to highly educated men, mostly faculty at leading universities like the UW, who chose to leave their jobs during wartime to serve their country.

A decorated veteran of World War I, Holt’s patriotic instincts spurred him to once again act on behalf of his country in September 1941, three months before Pearl Harbor, when he sensed America’s entry into World War II was only a matter of time. Little did anyone know that this scholar, teacher, husband and father—perhaps best known for his 1933 book Treaties Defeated by the Senate, which became a standard in many graduate courses—would go on to become a hero during the second world war. But looking back on Holt’s life, it really shouldn’t have come as a surprise.

During World War II, Holt fashioned a magnificent collaboration with MI-9, the British intelligence service which saved the lives of thousands of Allied pilots (and others) who were behind enemy lines. For his top-secret work in the field known as “Escape and Evasion,” Holt received the most prestigious honor the British government can bestow on a foreigner—the Order of the British Empire. Uncle Sam presented him with a Silver Star, one of the highest military decorations.

But the legacy of this professor, who retired from the UW in 1967, runs much deeper than the life-saving work he did in Europe 70 years ago. The escape-and-evasion theories and techniques he developed then are still being used today by the U.S. military. An East Coaster through and through, W. Stull Holt was educated at Cornell and George Washington University. He was making his mark on the faculty of Johns Hopkins in Baltimore when Solomon Katz, the renowned UW history professor and administrator, came calling to bring him to the Pacific Northwest. Here, he was one of a legion of “Warriors Intellectual” who made such a difference to this country.

The rise of the Warrior Intellectual

Perhaps the most famous American example of a “Warrior Intellectual” is Theodore Roosevelt, outspoken proponent of “the strenuous life.” While not an academic, he was a prodigious intellectual, a serious reader and accomplished writer on a wide range of subjects. His book on the Naval War of 1812, for instance, was regarded by the Royal Navy as the authoritative scholarly work on that subject.

Yale historian Robin Winks understood the theory underlying the concept of the “Warrior Intellectual.” In his book Cloak and Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961, Winks wrote about a contingent of Yale professors and students who interrupted their campus lives at the outset of World War II to join the un-uniformed spy ranks of the intelligence community—in this case, the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), forerunner of the CIA.

Those gentlemen did not fit the “Ivory Tower” stereotype widely applied to campus-bound scholars. Instead, they fill the subset of “Warrior Intellectual,” part of the larger group of “Active Intellectuals,” who don’t restrict their pursuits to college campuses but get involved in their communities, civilian and military.

Holt was a prime example of both groups, as his military (and political) careers attest. While the Warrior Intellectual, as a scholar, is primarily engaged with the “life of the mind,” he is just as willing to defend his country. Many did so during World War II, coming from Ivy League institutions and public universities—like the UW.

Winks’ book, which was published in 1987, explored the underlying bonds between the university and the intelligence communities. While it focused on the group from Yale, the book’s end notes state: “The story I would most like to be told is that of W. Stull Holt, the American scholar who was in charge of liaison with Britain’s MI-9, the escape-and-evasion operation that helped get downed Allied pilots (and others) out from behind enemy lines. Holt sought to achieve the same magic for the American Eighth Air Force, and though his work is attested to MI-9: Escape and Evasion, 1939- 1945, a book by M.R.D. Foot and J.M. Langley, there is an important record to be set straight. Holt had been a professor of history at Johns Hopkins and subsequently at the University of Washington, and I had known him and admired his work.”

Winks wasn’t the only one who thought highly of Holt. In 1988, historiographer Peter Novick, in his history of the historical profession, That Noble Dream, validated Holt’s commitment to action in the public arena as well as to ideas and ideals by calling him a “belligerent interventionist.”

Thomas J. Pressly, the late, legendary UW history professor who was brought here by Holt himself in 1949, once wrote that, “Stull declared war on Germany in 1936, although the U.S. did not get around to that position until 1941. I suspect that Holt never rescinded his 1914 declaration of war on Germany, but just suspended it from 1918 to 1936.”

Theodore Roosevelt perhaps summed it up best when he wrote: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood … if he fails, at least [he] fails while daring greatly. So that his place will never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory or defeat.”

Clearly, minus Roosevelt’s nasty assesment of sideline critics, Holt meets the standard, a true avatar of the “Warrior Intellectual.”

The Great War beckons

This 1919 issue of the American Field Service Bulletin pays tribute to Americans like Holt who lived in France and served so admirably as ambulance drivers during the first world war.

In 1917, Holt left his studies at Cornell to join the American Ambulance Field Service in World War I as an ambulance drive attached to the French army. He subsequently joined the American Air Service, where he won his wings; and, as First Lieutenant, flew combat missions as an observer-bombardier-gunner, and was wounded and gassed. For his contribution to the Allied war effort, the French awarded him the Croix de Guerre. (Holt’s World War I career is traced by Pressly in The Great War at Home and Abroad: The World War I Diaries and Letters of W. Stull Holt.)

After “the Great War,” Holt returned to Cornell, where he completed his undergraduate degree under famed historian Carl Becker, his M.A. at George Washington and his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins. He then settled into the academic life, teaching and writing. He followed public affairs keenly and was never an ivory-tower intellectual; his military interventions showed otherwise, as did his political activism: he was a two-time delegate to the National Democratic Convention and a member of the Platform Committee.

Holt returns to war in a different role

On a trip to Washington, D.C., in September 1941—three months before Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor—Holt called on the War Department, hoping to be cleared for a combat flying role. His age of 45 unsurprisingly disqualified him, but one Air Corps officer, recognizing Holt’s trained skill in the gathering, evaluation, and transmission of evidence, told him that he was fit for intelligence work as a staff officer.

After months of waiting for an assignment—a War Department acquaintance had alerted him that the Department had been swamped with similar requests—he wrote an old Baltimore friend with close ties to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. Holt’s letter explained that this was the only time he had ever asked for a favor of this kind. The activist urge of the Warrior-Intellectual had prevailed over any favoritism concern.

On July 24, 1942, Holt finally received his orders from Major General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, the legendary commander of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, based in England. Spaatz knew British Brigadier Norman R. Crockatt’s intelligence operation and wanted an American clone.

Holt’s mission: emulate Crockatt’s success to serve the fliers of the Eighth Air Force. While Holt would no longer experience the thrill and danger of combat flying, this assignment was the next best thing—his ticket to a command position in the dramatic, thrilling world of “escape and evasion” and in its connected responsibility of interrogation. Interrogation involved three main components: debriefing Allied fliers after successful missions; interviewing “escapers and evaders” (those who escaped from German prisoner camps or those who parachuted or crash-landed and then evaded capture, navigating pre-designated escape routes to “safe houses” and “helpers” who led them to freedom); and finally, getting information from German prisoners of war – fliers and ground forces, after Holt’s responsibility was enlarged after the D-Day invasion to include ground troops.

A perfect model: Brigadier Crockatt

Britain, entering World Wars I and II at their outset, developed a sophisticated military intelligence infrastructure composed of a set of “MI’s.” By the end of 1941, these units, commanded by Brigadier Norman R. Crockatt, were in charge of managing two areas of military intelligence: one concentrated on communication with British and Commonwealth POWs, escapers and evaders; the other unit oversaw interrogation of enemy POWs.

Holt was not just impressed with the way the British organized its intelligence program. He was also taken with Brigadier Crockatt’s leadership abilities. Holt, already an Anglophile, came to see Crockatt as the best of the best — not just respected but revered by his men. Holt followed suit, and soon he, too, became revered by his staff. What made Crockatt such a brilliant leader was that, as a twice-wounded, twice-decorated infantry officer in World War I, he understood the divide between combatant and staff, and worked to reduce it. Crockatt was “clear-headed, quick-witted, a good organizer (sic), a good judge of men and no respecter of red tape,” according to the book written by Langley (himself an escaper) and Foot (himself an academic don from Cambridge).

Early on, while forming his unit, Holt made a key decision that reflected similar personal qualities as well as his respect for the network Crockatt had built. He decided to use the British escapeand- evasion system and not attempt to create separate American organizations in German-occupied countries.

After the war, Holt characteristically commented on the oddity of making that decision without consulting anyone. He found it strange that his decision was left to a civilian then in the uniform of a Major (italics added to reflect his wry self-image) with no real military training. Clearly, Holt displayed two crucial leadership traits: personal initiative as well as the ability to not let his ego get in the way. In 1943, however, Holt almost lost his command in a classic bureaucratic turf war with the Pentagon. An examination of relevant documents reveals that Crockatt took the rare step to intervene on his behalf with U.S. military leaders—a touchy matter across national lines. That helped convince General Jacob L. Devers, Commander of U.S. Forces in Europe, to keep Holt, a decision he defended with the remark, “They can’t run the war from Washington.” Also, perhaps, without the clearly functional Crockatt-Holt partnership.

The matter of the “other front”

Military historians are primarily concerned with why and how battles—and ultimately wars—are won and lost: the clash of arms, and the “big-picture” strategic, tactical, and logistical analysis. Holt was no longer eligible for this “fighting front,” but definitely for the “other front,” with its own set of strategy, tactics, and logistics. This was the front of “Escape and Evasion.”

The two fronts were conceptually interconnected in two crucial ways: returning escaped fliers to the front lines; and the gathering and protection of vital intelligence. (We must also not forget the importance of the creation of a communication system to maintain prisoners’ morale during the trying ordeal of imprisonment). Ideally, if “escape and evasion” worked properly, airmen who were freed from behind enemy lines could return to fighting status; that was how the “other front” resupplied the “fighting front.” Escape was almost the easy part. Evasion was trickier, involving the knack of inconspicuous travel; learning the escape lines; connecting with “helpers,” members of the “Resistance” who risked torture and death to man “safe houses” and guide evaders to ultimate rendezvous and return to England.

Each of these roles offered opportunities to gather valuable intelligence, such as: 1) how to identify guards who might be induced to aid escapers; 2) was there a change in the demographic of guards which might reflect a manpower shortage; 3) what population groups should be avoided, such as fanatical Hitler Youth or residents of heavily bombed areas, who were more likely to execute fliers summarily; and 4) what was the state of the German transport system? In addition, a special type of intelligence was required. It concerned Allied criminal behavior—that is, the identification of stool pigeons among our captives. Archival documents include Holt memoranda listing American personnel accused by fellow POWs of betrayal, to be turned over to the provost marshal.

It was the joint responsibility of MI-9 and Holt’s PW&X Detachment to train Royal Air Force and Eighth Air Force airmen to deal with missions gone wrong and to orient them to the ethos of the prisoner-captive relationship, as defined by the Geneva Convention of 1929.

“Name, rank and serial number”

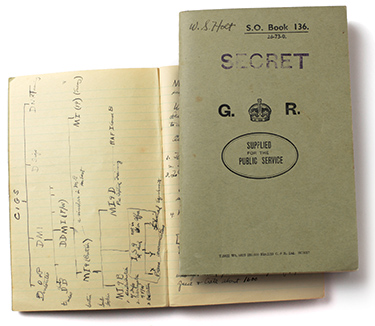

In this notepad–supplied by the British government–Holt took notes about his top-secret work training Allied forces about escape and evasion. “In teaching code,” he wrote, “don’t let boys talk outside the classroom about the codes.”

The standard “greeting” of the German prison camp commandant to Allied captives was emphasized that their war was over. We can easily imagine the silent response: “That’s what you think.” They were taught by Crockatt and Holt that their war was not over, that it was their duty to attempt, repeatedly, to escape, evade, and ultimately return to their units to resume their active role in the war effort. The 1929 Convention protected them against harsh punishment for escape efforts. The Convention had also permitted them to limit their responses during the inevitable interrogations quickly following their arrival to “Name, Rank, and Serial Number.” Their pre-mission lectures emphasized that what we now call “enhanced interrogation” was illegal. But the imposition of some discomfort, for example, exposure to heat or cold, though not protracted, was used by both sides, along with well-practiced “good cop/bad cop” techniques.

When positions were reversed, with the Crockatt/Holt team acting as interrogators of German POWs, the information-gathering system process was enhanced by hidden microphones secretly recording conversations between prisoners. (Documents detail fascinating transcriptions of German generals agreeing, in essence, that things would have been different had they, and not that idiot Hitler, been running the war; and that they were doing their jobs as professional soldiers, not as Nazi ideologues.)

Rewarding the “helpers”

When Allied prisoners escaped confinement, they were considered “evaders.” They then made contact with the “helpers,” whose noble efforts did not escape the Germans. In the summer of 1944, the Germans established in Paris the SD (SichersheistDienst: Security Service) for Counter-Evasion. By 1944, the Germans had penetrated or broken up many of the Allied evasion organizations operating in enemy-occupied territory. So successfully had they learned the methods of these organizations that they were able to organize large-scale counter evasion services of their own.

One document lists 168 U.S. and British escaped POWs who were recaptured; and, contrary to any convention, were sent to Buchenwald, where two of them died in that notorious death camp. Obviously, many more “helpers” met a similar fate.

Holt knew very well the dangers his team of “helpers” were facing every day. He later selected Major John F. White to head up a new awards unit which recognized and rewarded those who risked their lives to help Allied prisoners get home to England and Alliedcontrolled Europe.

The result, approved by the chief of G-2 [Intelligence Dept.], was a complex system of graded awards—reimbursements and decorations. The gratitude of the helpers is documented by a deluge of emotionally charged thank-you letters received by White’s special unit. There was another kind of award as well. Captain Dorothy Smith, sent to Brittany to certify the contributions of a legendary Resistance leader, went beyond the monetary: she married him.

How much success? A look at the numbers

The number of escapers and evaders, as calculated by the British War Office, tells an amazing story of endurance and success for the thousands of people who risked their lives after being behind enemy lines.

These figures reflect the fact that Britain had been fighting in all theaters of World War II, involving significant numbers of fighting men, since 1939. This early phase of the war was more a time of defeat—and capture—than of victory. The numbers cover the war theaters of Western Europe; including neutral Switzerland, which was a key haven, largely for escapers; and the Mediterranean, the latter because in 1943, Holt’s responsibilities had been enlarged beyond the Eighth Air Force to include army ground forces in preparation for the invasions of North Africa and Europe.

British, including Dominion, Colonial, and Indian personnel: Escapers: 18,703. Evaders: 4,116. Total: 22,819. U.S.: Escapers: 1,806. Evaders: 5,653. Total: 7,459.

Holt’s military legacy

While researching the Holt story, I learned that Suzzallo Library had been contacted by Colonel (Ret.) Greg Eanes, who had a special interest in learning more of Holt’s “back story” as well as of his military career. He had hoped that the library and Holt’s family might have relevant documents. Suzzallo had plenty regarding Professor Holt. The family had plenty of material, which I had been examining through Tom Pressly’s intervention and the family’s cooperation, regarding Colonel Holt. Eanes, whom I met months later at the National Archives, had an understandable motivation. He was the Holt of the Gulf War of 1991, managing “Escape and Evasion,” and realized his huge debt to Holt’s methods and philosophies, which underlay his own. He also concluded that, besides the book MI-9, Holt—who died in 1981 at the age of 86—had not received anywhere near due credit.

The relevance of the liberal arts

How are Holt’s actions ascribed to a liberal arts/social science curriculum? The first is his decision to emulate, but not necessarily duplicate, Brigadier Crockatt’s highly effective team. He chose cooperation over competition, allowing his unit to use British experience to shorten the learning process. Holt’s value system permitted the application of cool reason to answer the central question: how most quickly and effectively could he bring his command up to speed? Others might have promoted a spirit of competitive nationalism— Yanks over Brits: we’ll gain our own experience and do better than they. I argue that the values of a liberal arts education helped point Holt to his decision. It reflected a proper choice of values.

The second instance was Holt’s deep concern to recognize the huge and high-risk contributions of the gallant members of the Resistance in the occupied countries, without which the success of Escape and Evasion would have been critically at risk. To Holt, recognition meant real follow-through: the establishment of a unit solely devoted to that end. It is not difficult to recognize here a profoundly meaningful application of humane values to the terrible realities of war.

It is also not difficult for those who studied the liberal arts and social sciences at the University of Washington, some perhaps with the guidance of W. Stull Holt, to feel a measure of institutional pride … and to recognize that Yale historian Robin Weeks’ specification had, indeed, a good measure of justification.

With deep gratitude, this article is dedicated to the UW, especially its stellar History Department and magnificent Suzzallo Library, where I studied and researched, guided by professors and archivists who became both mentors and friends. The University has become the focus of my and my wife Rosemary’s educational and social lives, and we feel deeply indebted to it. In addition, we honor two remarkable people who died in 2012 and without whom this effort would never have even been conceived: Professor Tom Pressly and Jocelyn Holt Marchisio, loving and admiring elder daughter of Stull Holt. Stull brought Tom to the UW. Jocelyn welcomed Rosemary and me into the family, with full access to the Holt family papers. Ave atque vale!