At about 3 in the morning on Aug. 19, 1976, Dan Evans got a phone call with some disappointing news: he would not be Gerald Ford’s running mate in the upcoming presidential election.

Everyone from a coalition of Republican governors to Ford’s own son had been telling the president to pick Evans. But during the primaries, a strong challenge from archconservative Ronald Reagan had worried Ford—enough to tip the balance in favor of Bob Dole, a war hero whose voting record in the Senate made him more palatable to the right wing.

Ford probably should have listened to the Evans advocates. Dole’s abrasive style didn’t do their campaign any favors at a time when voters wanted to heal the wounds of the Watergate years. “I got to know Bob Dole when he was Senate leader,” Evans recalls, “and he was a very funny guy. But he didn’t come across that way in that campaign. And that was a very, very close campaign. It wouldn’t have taken much for a Ford victory—a shift of 6,000 votes in Ohio and 3,000 in Hawaii.”

Evans has visited many sitting presidents in the White House, including Ronald Reagan. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

It wasn’t the first time Evans’ name had nearly appeared on a presidential ticket. In 1968, Richard Nixon had strongly hinted that an endorsement from Dan Evans at the Republican National Convention would be repaid with a vice-presidential nod. Evans thanked him and proceeded to support the lost-cause candidacy of Nelson Rockefeller.

For admirers of Dan Evans—and they are legion—it’s a bit painful to think about how little seemed to stand, at various times, between him and the presidency. If he’d taken Nixon’s bait, for example, he would’ve been in a position to inherit the Oval Office after Watergate.

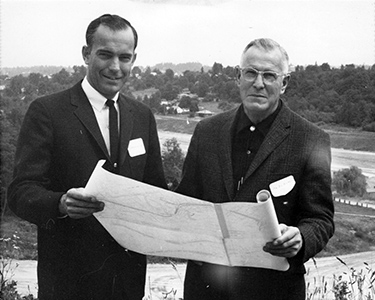

Evans himself, now 81, freely admits that he felt qualified for the nation’s top office, and believes he could have put together a strong administration. But he also admits that he “didn’t really thirst for the presidency” the way others have. His first priorities have always been his family and his home state. And he never had much patience with the back-scratching and superficialities of national politics. At the start of his third gubernatorial term, when speculation that he might seek the White House in 1976 was widespread, Evans grew a full beard—unheard of for a presidential aspirant. (One fellow governor quipped, “I think you’re running for president—but you’re 100 years too late.”)

Evans with Richard Nixon. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

Washington, D.C.’s loss has been the other Washington’s gain. In addition to his three successful terms as governor, Evans has given the state five years of able representation in the U.S. Senate, eight years in the state House of Representatives, six years as president of the Evergreen State College, twelve years on the UW Board of Regents, and a lifetime of loyalty. He is perhaps the most popular and influential political figure in the state’s history. “He just lives integrity,” says Sandra Archibald, dean of the Daniel J. Evans School of Public Affairs. “We call him a compass, a moral compass for future leaders. One of the main reasons this school was named after Dan is that he has this blend of lofty ideals and a practical approach. It’s a combination that’s really, really rare in a politician. He has the ideals, but he knows how to get things done.”

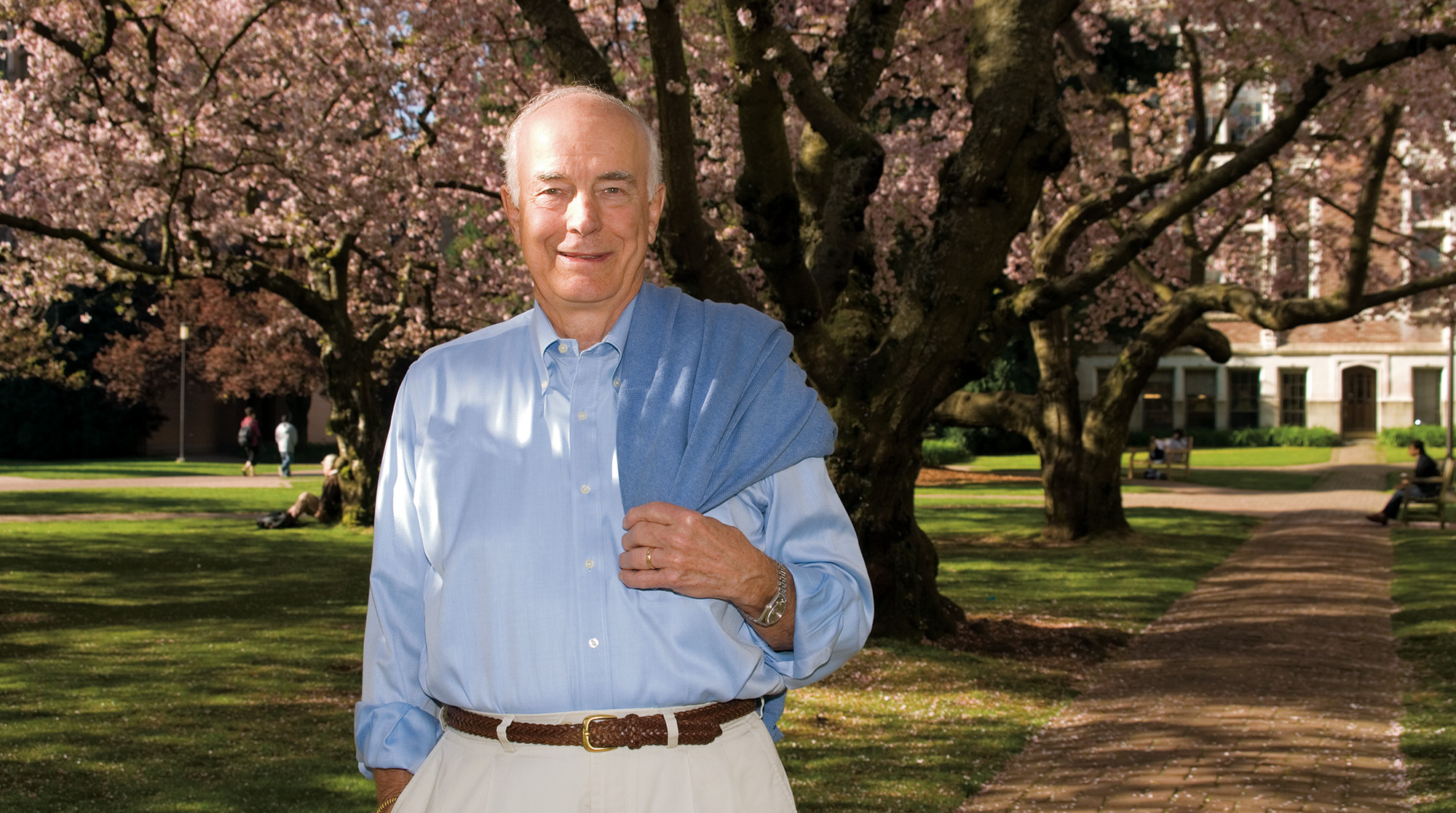

This year, to mark the 50th anniversary of his entry into public leadership, the University of Washington and the UW Alumni Association have named Daniel Jackson Evans, ’48, ’49, the Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus—alumnus of the year. It’s the highest honor the University confers upon its graduates, and Evans is its 67th recipient.

***

When Dan Evans’ family first came to the state of Washington, there was no state of Washington. In 1859, the year his great-grandfather settled in what is now Port Gamble, there were 500 people living in Kitsap County—making it roughly twice the size of King County—and fewer than 12,000 in all of Washington Territory. Three decades later, Evans’grandfather served in one of the young state’s first senates.

Evans grew up in Laurelhurst and attended Roosevelt High School, where, seeking the junior class presidency, he suffered the only electoral defeat of his life. After graduating in 1943, he went straight into the V-12 naval officer training program. His first duty station was the UW, although the Navy moved him to an ROTC program at the University of California-Berkeley after only eight months.

By the time Evans deployed to the Pacific as a commissioned ensign, the war was over, and he spent much of 1945–46 on aircraft carriers, helping to bring soldiers and planes back home. When he returned to the UW in the fall of ’46, he felt too old and impatient for extracurricular activities. He buckled down, studying civil engineering under many of the same professors who had taught his father 30 years before, and completed a B.S. in 1948 and an M.S. the following year.

After graduation, Evans took a job on the city of Seattle’s structural engineering design team, where he helped draw up plans for the Alaskan Way Viaduct. “I figure that I’ve lived too long,” Evans jokes, “because that marvelous, permanent structure that I helped design is now under fire and they want to take it down.” (Despite his sentimental attachment to it, Evans has forcefully argued for the viaduct’s replacement by a tunnel.)

One day in 1956, Evans called up Bill Douglas, ’55, and told him he was considering running for the state legislature. Although he was several years Douglas’s senior, Evans felt that a friend with a political science degree might have some useful insights.

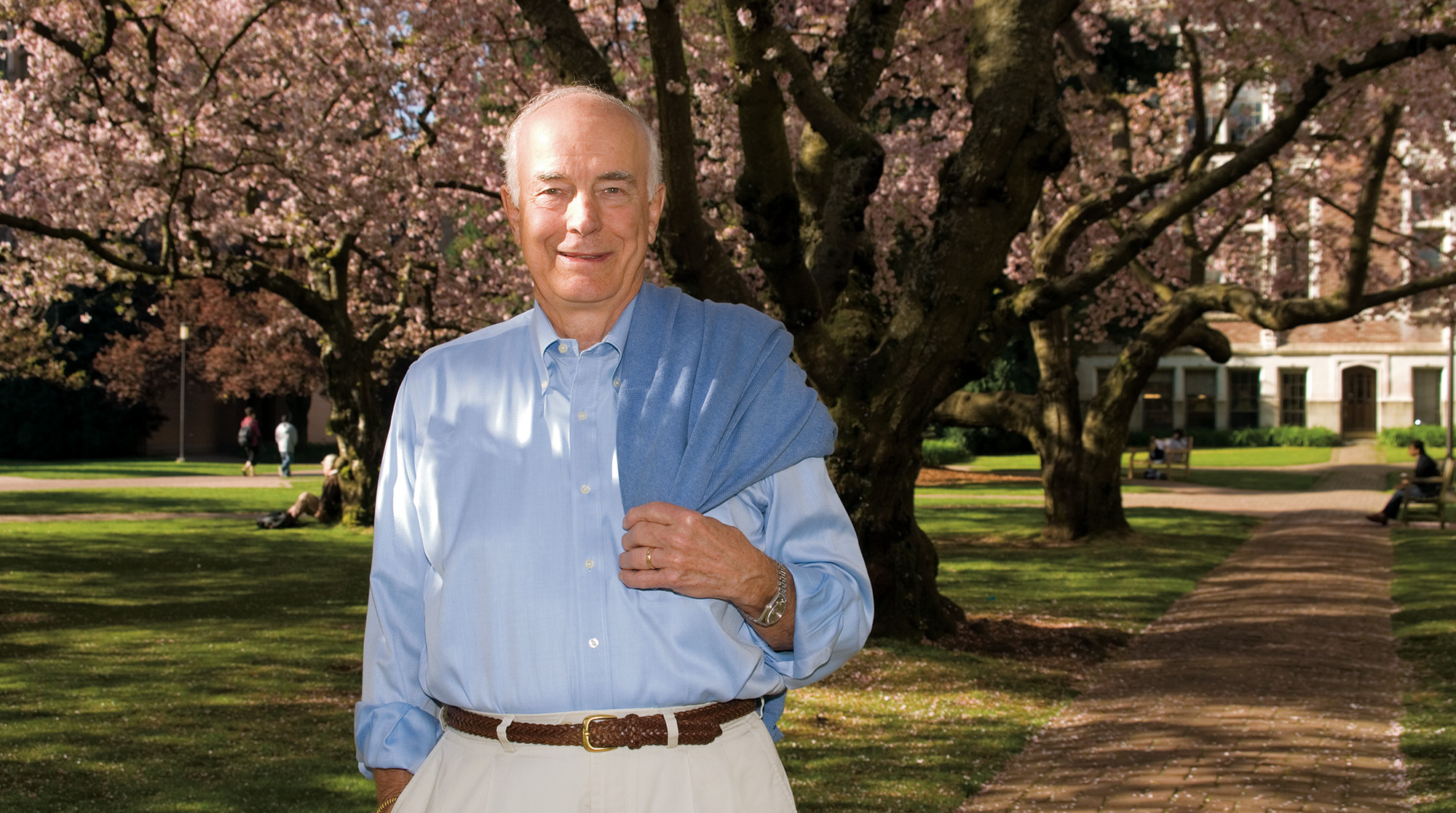

Dan Evans with his father and fellow engineer Daniel L. (Les) Evans, 1917. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

“There was a long silence on my end,” Douglas recalls, “and finally I said, ‘Well Dan, I think that’s wonderful, and you’re a terrific engineer, but you know you’re not the world’s greatest stand-up public speaker.’ In fact, he was a terrible public speaker. And Dan said, ‘Well, I’ve taken that into account. I’ve spent the last year going to the Toastmasters club, and I’ve just won the prize for the most improved member.’ ”

Douglas now admits he should have seen this coming from his former Boy Scout troop leader—an Eagle Scout who had so deeply internalized the motto “Be Prepared” that on outings with him nothing ever went wrong. Evans, of course, would go on to win not only the 43rd District legislative race but every subsequent race he entered. (He would also become known for his prowess at the podium, appearing on the cover of Time magazine in 1968 as the keynote speaker at the Republican National Convention.)

Once in office, Evans invariably took the same approach to problems and needs—identifying them early, sometimes before they even arose, and addressing them with aplomb and humility. In his first term as governor, from 1965–69, he worked with a divided legislature to create the state community college system and secure huge increases in funding for education. In 1970, he established the first state-level Department of Ecology, which the Nixon administration would later use as a blueprint for the creation of the federal EPA. In 1974, Evans launched the ambitious “Alternatives for Washington” program—a survey of the state’s citizens that drew 70,000 responses and would influence policy for decades to come. “It was amazingly far-sighted,” Archibald says of the program, which yielded policies covering everything from transportation to education to social services with a heavy emphasis on environmental protection. “If you look back at that agenda, we’re still working on it. And that was 30 years ago.” Following a 1981 study by the University of Michigan, Evans was named one of 10 outstanding governors of the 20th century.

Dan Evans: as a briefly bearded governor in 1973. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

Evans also fought tirelessly, and without success, for a state income tax. In fact, the self-styled conservative took up some improbably liberal-looking causes during his tenure as governor. But Evans insists that an active state government, far from being incompatible with conservatism, is the embodiment of it. The best way for governors to keep power from concentrating in a bloated federal bureaucracy, he says, is to keep things running smoothly at home.

“I’ve given innumerable speeches along that line,” he says. “I’m writing an autobiography now, and I was just rereading one of my speeches a few days ago—I was admonishing the audience about the need for state government to really step forward and do its task, or else prepare for an orderly handover of state responsibility to the federal government.”

Evans is sorry that the popular definition of conservatism has so narrowed in recent decades. And he laments the decline of bipartisanship, which was always his preferred way of getting things done. Neil McReynolds, ’56, Evans’ long-time press secretary, remembers the governor saying over and over, “There aren’t Republican solutions or Democratic solutions. There are the best solutions. That’s what I’m looking for.” And he wasn’t just saying it in speeches, McReynolds adds, but in private conversation. “It was just the way he felt about things.”

When Henry “Scoop” Jackson, ’32, died in 1983, Washington voters chose Evans to complete his Senate term. Evans went east with high hopes, but found the next five years disheartening. In April of 1988, he published a grumbling essay in the New York Times Magazine called “Why I’m Quitting the Senate.” “I have lived through five years of bickering and protracted paralysis,” he wrote. “Five years is enough.” In characteristic form, Evans tried to help fix the system even as he was washing his hands of it. His essay concluded with a set of proposals for the Senate, including a two-year budget cycle and a streamlining of the committee system.

Evans fears that Congress has only further deteriorated since his departure. “Negative campaigning creates bitterness that carries over into public office,” he says. A case in point is the fate of the Senate softball league, one of the few things Evans remembers fondly from his Beltway years. Senators and their staffers from both sides of the aisle used to play friendly games every spring—Evans and fellow Washington Senator Slade Gorton fielded a team named, inevitably, the Washington Senators. “And it was fun,” Evans says. “You’d play other Senate offices, and after the game—it didn’t matter who won—you’d all go off to have a beer together.” The league fostered a kind of easy camaraderie, Evans remembers, that made cooperation that much easier on Capitol Hill. “Well,” he says, “I heard recently that they’ve now divided it into two leagues, Republican and Democrat. Stupid. Just stupid.”

***

One institution that’s moving in a more promising direction, Evans says, is the University of Washington, where he has been happily focusing his energies in recent years. He’s active at the school of public affairs that bears his name, speaking to seminars and meeting individually with students and fellows. He helps out with UW Athletics. His dozen years of service on the Board of Regents, including a term as its chairman, ended last year. Now he’s vice chairman of the UW Foundation Board.

“The current feeling I have about the University is one of real pride,” he says. “I think the faculty and the management of the University have caught on faster to what’s necessary now in higher education than most other universities. And you can put Harvard and Stanford and a lot of the very fine ones in that category. They’re still basically stove-pipe institutions that depend heavily on departments. Interdisciplinary work is not easily done, and not valued as highly. I’m looking at them from the outside, of course, but I think the University of Washington has been very, very successful in its interdisciplinary work, and that is where universities have to be today because the barriers between disciplines are just breaking down.”

Evans as U.S. senator on Capital Hill, circa 1988, with wife Nancy and sons (from left) Bruce, Mark, and Daniel Jr.. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

Evans says he’s particularly proud of what a high priority the UW has made its undergraduates—he mentions the expansion of research opportunities for young students, and the adoption of the Students First and Husky Promise initiatives to help them pay for school. In January, Evans speed-walked the Seattle Half Marathon on two artificial knees to benefit Students First, completing the 13.1-mile trek in three hours and change and raising more than $100,000 for the scholarship program.

“Everybody bet he couldn’t do it as fast as he did it,” says Douglas, who still goes on long hiking excursions with Evans almost every year. Douglas marvels at the energy of his octogenarian friend, both physical and mental. He says Evans plans their trips just as meticulously as he did back in the Boy Scouts. “He sent me a Christmas card that said, ‘This half-marathon is just a warm-up for next summer, Bill.’ So I guess we’re going somewhere in the summer.”

Evans’s gubernatorial portrait, by Alvin L. Gittins. Image courtesy of Dan Evans.

As a legislator and as governor, I kept talking to my department heads and others about understanding demography.

And so we saw this bulge coming. The very first thing that I advocated and we got through were big bond issues for school-building construction. That was followed by the community college system and the Evergreen State College. And we also had … boy, the University of Washington would die if it got the kind of increases we got for it back then. In one session, 1967, I think we got a 22 or 23 percent increase, all for the same reasons. We needed that expansion.

And then people worked together pretty well. There wasn’t a whole lot of partisanship because everybody knew what the problems were. There was no differential between Republicans and Democrats to any degree about the need for supporting common school education.

I supported George W. Bush in his first election campaign, strongly. He advertised himself as a compassionate conservative. And I said, “That’s a pretty good combination.” So I was really enthused, and then, ultimately, really disappointed—not just because of Iraq, but because the conservatives who grabbed hold manned all of the politically sensitive positions in the departments and in the White House, and they were ruthless. And it didn’t serve the president well, and it certainly didn’t serve the country well.

So I hope we have—I have to use a term I don’t like very much, but I’ll suppose I’ll use it—I hope our next president has a broader bandwidth.

When you run for office, you run as a representative of a party. When you’re elected to office you’re elected to govern all the people. You can bring your philosophies to bear, but don’t use the philosophies to divide people. Use the philosophies to bring them together.

Nancy always has been an absolutely superb partner. She was much better than I was in the early stages of our campaign. She mixed better than I did, was more gregarious.

The day of my first inauguration, I was already in Olympia, and she came down that morning. She left our house in Laurelhurst, packed the station wagon, had two kids with her. Our house was on a hill, and as she started up the hill, the back door of the station wagon fell open and her ball gown and everything just fell out the back. Neighbors shouted at her, and she had to stop and pick all that up. And when she got down to Olympia, we found that it was not only the inaugural ceremony but a big luncheon afterwards and then two receptions and then the governor’s ball and then a late-night party at the mansion. And interspersed with all of that was a live broadcast from the mansion, with a tour. Chuck Herring was the KING-TV newscaster, and almost the first question he asked was, “Well, Mrs. Evans, at age 32 you must be the youngest first lady in the state’s history.” And Nancy just looked at him, and said, “I’m not 32, I’m 31.” It was a marvelous start to the whole thing. And then she led them through, and she talked with such authority about all of the rooms and furniture and artwork in the mansion. We got done, and I said, “Nancy, we’ve only been here for about four hours. How did you know all that stuff?” And she said, “Well, I paid attention when I came over here for teas that were being held under Governor Rossellini. I just listened.”

We’ve got nine grandchildren and they’re all terrific. And of course the name continues, because Dan and Celia’s youngest child is named Daniel Jackson Evans III. But he refuses to go by Dan. It got too complicated. So he chose. He said, “I’m Jackson.” And you can’t call him Jack.