In 1969, James A. Banks was wrapping up his doctorate in education at Michigan State University when a UW professor visited campus. The professor, who was there to present a lecture, asked about top students near graduation. Banks’ advisor pointed to the bright, young graduate student. “That was recruitment,” Banks says. “In those days, hiring was done person to person.”

The UW flew Banks to Seattle to visit the College of Education and interview. He was drawn to the position because it was situated in diverse communities that included Hispanic and Asian people, not just Black and white, and that’s where he wanted his research to focus.

When the offer came, it included a salary of $15,000, a few thousand dollars higher than the typical starting salary at the UW. The dean knew what he was doing, says Banks. The offer made him feel valued as he settled into campus.

Banks arrived in the first university-wide effort to recruit faculty of color. The push came in the wake of student activism that culminated in spring 1968 with a Black Student Union-led sit-in in President Charles E. Odegaard’s office. On the students’ list of demands was recruiting Black teachers and administrators. Starting in the fall of 1968 with the hiring of 12 Black instructors to tenure-track and lecture positions on campus, an era of seeking out top scholars of color began. In 1970, the UW invited Jacob Lawrence, an artist of international renown, to teach in the School of Art. Then came the hiring of other promising intellectual leaders, including Thaddeus Spratlin in the School of Business, Colleen McElroy in English, Carlos Gil in History, Marvin Oliver in American Indian Studies and Tetsuden Kashima in Asian American Studies. Samuel E. Kelly, ’71, became the UW’s first Black senior administrator, taking on the role of vice president of minority affairs and overseeing the program that is known today as the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity.

“We don’t want to just look diverse. We want to be diverse. And we want our university to feel diverse ... We are really just getting started in the hard work.”

Mark Richards, UW Provost

Banks has studied the issue of bringing diversity into education from many sides. He started his career helping educators of all identities find ways to teach Black experience, an effort born out of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. He understood and argued that all aspects of a school had to be examined and changed—from policies and teacher attitudes to textbooks and teaching styles. His work evolved to focus on ethnic groups in education and then developed into the discipline of multicultural education.

A stellar scholar, Banks received tenure in the College of Education in 1971. He became a full professor in 1973, quickly rising as a leader in his field. Today, he is known as the founder of multicultural education.

When he was mid-career and clearly a leader in his field, Kent State lured him with an offer of an endowed chair, a research assistant and a higher salary. “But UW matched the salary and the other stipulations of the offer and promised me they would search for the endowed chair,” says Banks. “So I stayed.” He became the Kerry and Linda Killinger Endowed Chair in Diversity Studies.

From Banks’ point of view, the UW and the college did many things right. He felt valued, his scholarship was widely accepted, and he was honored and promoted throughout his career.

But how has the UW fared since that first push to diversify brought Banks and others to campus in the late 1960s and early 1970s?

Rickey Hall

“In the last 50 years we have made some progress,” said Rickey Hall, the current vice president of minority affairs and diversity. Hall spoke in March at a university-wide forum hosted by Provost Mark Richards.

In the recent years, the UW has seen the highest racial and gender diversity among students in its history, “and yet we have fallen short on our faculty diversity efforts,” Hall said. When it comes to racial—and in some cases gender—diversity, the UW is behind national averages. The percentage of Black faculty at the UW has not increased in a decade. “For those who care about diversity, this should be distressing,” he said.

Several of the changes the BSU called for in 1968 mirror the new list of demands from the BSU in 2020. “The question we all should be asking is how do we accelerate change and assure that in 10 years students aren’t raising the same issues and concerns that were raised in 1968 and in 2020,” said Hall. “Diversity is everybody’s work,” and we need to be thinking about it every day.

Conversations around the country, particularly at public institutions, focus on not only redoubling efforts to ensure equal access for all students, but on looking anew at what diversity can contribute to learning, discovery and community engagement. The work ahead includes training across the university, said Hall. “We have a responsibility to help people understand what they don’t know and to develop new knowledge, skills and habits that will help them work more effectively across differences.” The work also requires a focus on equity in all aspects of University decision-making, he said.

In February, Provost Richards announced a new faculty diversity initiative, to which he was providing $5 million for hiring faculty to the Seattle campus over the next two years. The effort builds on the years of work of individual faculty members—like Banks—who have recruited and mentored new faculty, he said. The chancellors at UW Tacoma and UW Bothell are similarly directing funding for recruitment to those campuses, he said.

“If our faculty, staff and students better reflect the people in our communities, our campuses will become more welcoming to all people,” he said. The changes to come include public art and names on streets and buildings and statues. “We don’t want to just look diverse,” Richards said. “We want to be diverse. And we want our university to feel diverse … We are really just getting started in the hard work.”

Recently, the University has made key equity-driven hires across campus. This May, for example, Karen Thomas-Brown joins the College of Engineering as the new associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). She comes from the University of Michigan’s College of Education, where she was a full professor. In addition to her strong academic background, Thomas-Brown is a faculty leader in inclusion and anti-racism. Positions similar to hers have been developed and filled in colleges around campus, embedding the work of DEI—not just around faculty hiring, but in all aspects of teaching, research and management—at a high level in deans’ offices.

Banks, with his experience as a specialist in multicultural education, suggests the UW explore making cluster hires of new faculty to assemble groups of diverse educators who share a research focus across disciplines. They can build a community and provide support to one another, he says.

But simply recruiting faculty and staff and students to increase representation on campus is not enough, said Richards, explaining that it’s time to improve onboarding and develop a better understanding of BIPOC faculty experience from the time they arrive and throughout their careers. “We need to change the campus climate so that they want to stay, and they can thrive here,” he said. “We have a unique opportunity right now to change, … We need to ask ourselves what we have learned over the past year and how we can use those lessons to shape the future of higher education.”

To watch a discussion about faculty diversity, visit the recent UW Provost’s Town Hall.

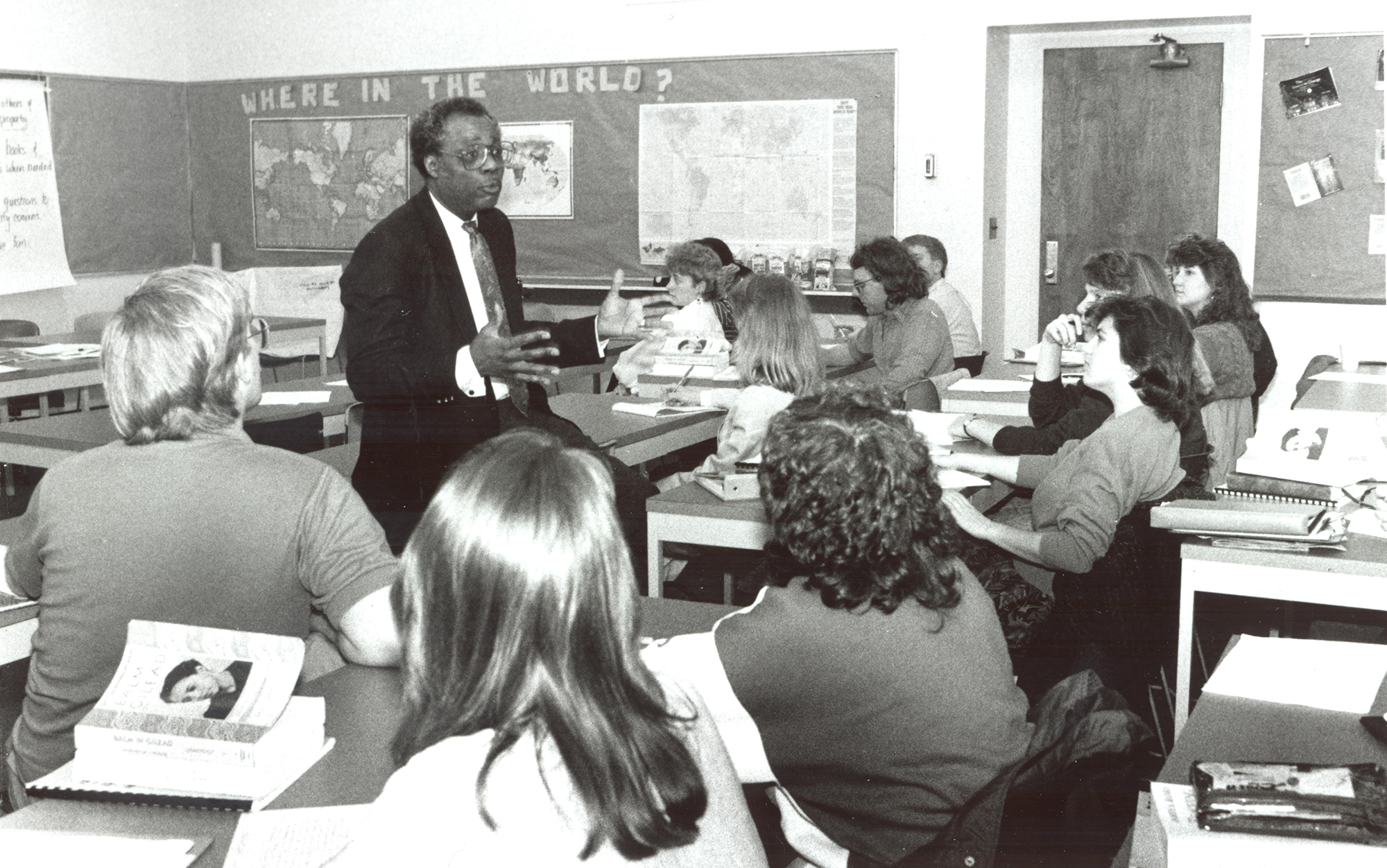

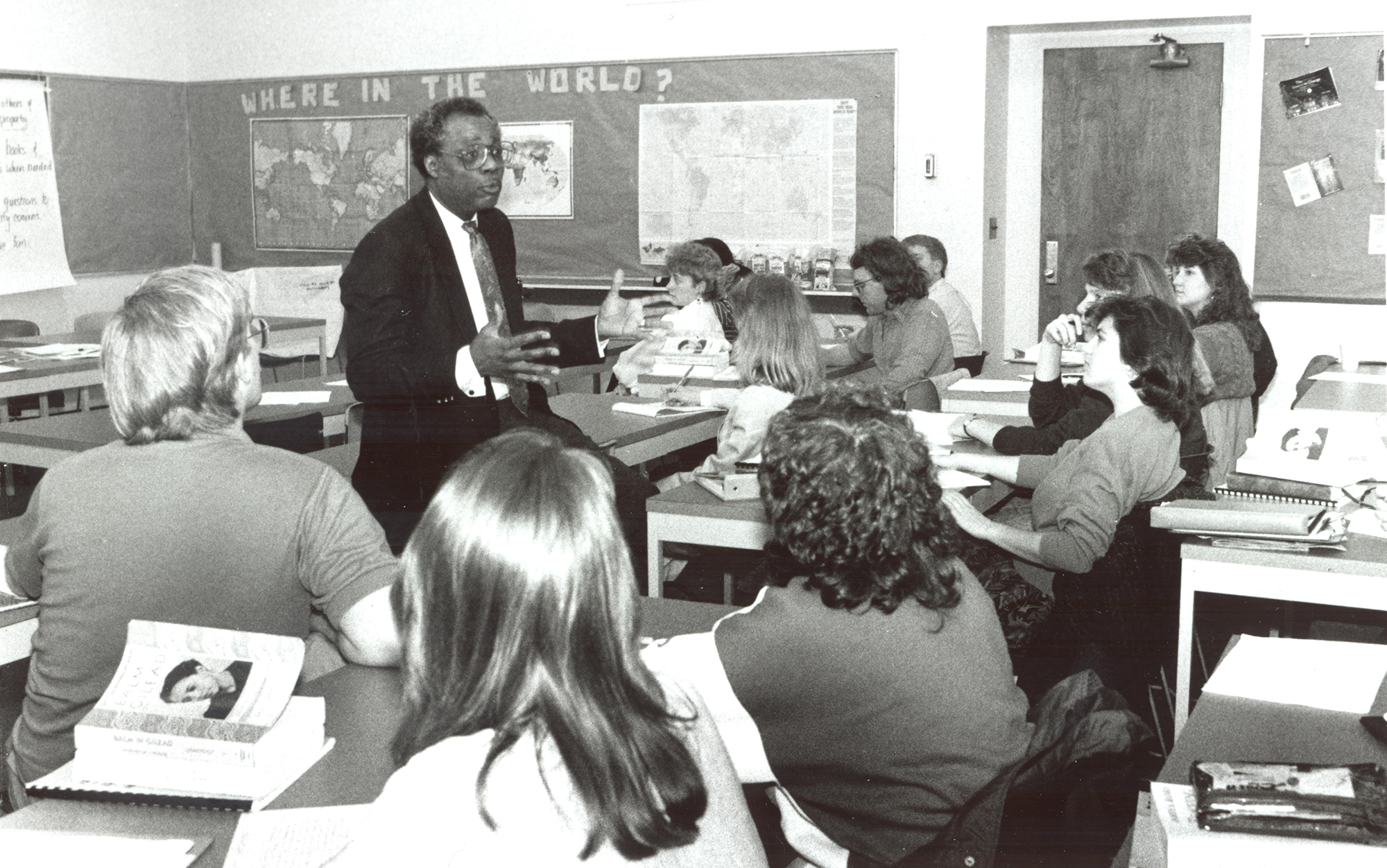

At top: James Banks joined the College of Education faculty in 1969 during the UW’s first push to hire promising and distinguished faculty of color. Here, in 1990, he shares his expertise on multicultural education with a class.