Seven men from the University of Washington—four professors and three alumni—have won the Nobel Prize. Bombarded by the media, showered with invitations and suddenly given thousands of dollars in prize money, the time of the announcement is a heady experience. But we wondered what happened next. Do you live happily ever after, both personally and professionally? Or should you be careful what you wish for, lest your dreams come true?

Columns tracked down the half-dozen UW laureates still living to find out. Our four faculty members continue to live in Seattle: Physics Professor Hans G. Dehmelt, who shared the 1989 prize in physics; Medicine and Oncology Professor Emeritus E. Donnall Thomas, who shared the 1990 prize in medicine for his work at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; and Pharmacology and Biochemistry Professor Emeritus Edwin G. Krebs and Biochemistry Professor Emeritus Edmond H. Fischer, who together shared the 1992 in medicine.

Surprisingly, the two living alumni laureates live only a few miles apart in North Carolina: George H. Hitchings, `27, who shared the 1988 prize in medicine; and Martin Rodbell, `54, who shared the 1994 prize in medicine. Our first laureate, George J. Stigler, `31, who won the 1982 Nobel Prize in economics, died in 1991. [Editor’s note: George H. Hitchings died on February 27, 1998, just a few days after this issue was printed.]

Each laureate had a distinct story to tell about the heady moment in early October (usually in the wee hours) when they first heard they’d won. Some were sure the phone call was a practical joke.

Once convinced it wasn’t a prank, they endured numerous media interviews and press conferences leading up to the award ceremonies. Two months later, on Dec. 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death, Sweden’s king presented them with their award in Stockholm.

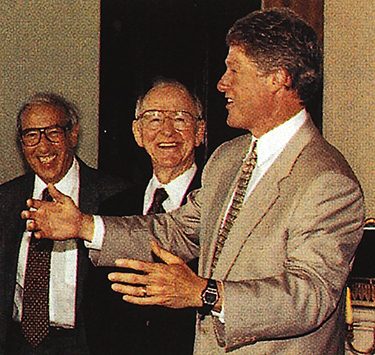

UW professors Edmond Fischer and Edwin Krebs attend a 1993 White House reception for Nobel laureates with President Bill Clinton.

Common themes wove throughout their stories. All felt that the blessings of the prize outweighed the burdens of celebrity, such as requests for autographs.

Contrary to certain stereotypes, they didn’t shift their research toward “riskier” directions after receiving the prize. “I used to think that if you won the Nobel Prize, you should turn to the hardest problem of all: how people think. But I’ve decided that’s a bit arrogant,” says Krebs. “Instead, our research has continued to guide itself. As it reveals new things, and generates more questions than any one lab can work on, we choose which to follow.”

Unlike some previous science laureates such as Linus Pauling and George Wald, UW prize-winners seemed wary of becoming public advocates for causes outside their own research.

“There’s a stupid misconception that you should know everything about everything, just because you won the Nobel Prize in a given discipline,” says Fischer. “The missionary spirit is just not my style.”

Still, several held (and occasionally expressed) strong opinions on social concerns, including population control, disarmament, and access to education and health care. Some are members of organizations, including Physicians for Social Responsibility and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

They were particularly bemused by continual demands to predict the future: “When they give you the Nobel Prize, they don’t hand out a crystal ball to go with it,” says Thomas.

A few suggested that their lives might have been different had they won the prize at a younger age. For some younger recipients—in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and even 50s—winning the Nobel Prize has been a mixed blessing.

Like a feted first novel, the prize is a tough act to follow. Young winners must struggle to break new research ground while juggling the demands of celebrity and living their lives in a spotlight. Often, they’ve failed to live up to other people’s great expectations. Some have even become severely depressed as a result.

But when these UW laureates won the prize, their ages ranged from 67 (Dehmelt) to 83 (Hitchings). By that time, all were renowned in their fields and secure in their work. Previous awards had already recognized their research, and they were juggling more demands to travel and speak than they could fulfill. For them, winning the Nobel Prize was like the icing on a cake. Their busy lives became busier, but the change was manageable.

Martin Rodbell (left) receives his Nobel Prize in Medicine from Swedish King Carl XVI during the 1994 ceremony.

Interestingly, Nobel didn’t originally conceive of the prize as the icing on anyone’s cake. Rather, he meant it to provide “such complete economic independence for those who by their previous work had given promise to further achievement that they could ever afterward devote themselves entirely to research.”

Still, Nobel lived in a quite different time, when there was no substantial institutional support for research, and experiments cost much less.

Our laureates say they face competing demands to, say, keynote a scientific conference, meet European royalty, hobnob on a talk show, speak at an Ivy League college commencement, or talk to students at a local elementary school.

Most of them say they choose which requests to honor based on a commitment to their local community—and an inverse correlation with status. They favor local schools and service clubs over prestigious universities.

“The big universities have plenty of occasions to hear people like us, but the schools and junior colleges usually don’t,” says Fischer, proudly displaying the brightly colored thank-you notes that elementary students had sent him.

“I enjoy the chance to touch young people’s lives,” he added. “It gives me an opportunity to relate to kids and tell them what science is and put it in a context that they can understand.”

“Too often, young students seem to believe that Nobel laureates must be beyond their understanding,” says Rodbell. “With me at least, these notions are generally disposed of. I hope to instill into students the idea that scientists are normal individuals with keen interests in learning about the nature of the living process and need not have extraordinary intelligence, capabilities, or privileges.”

Krebs agrees: “Often discoveries and prizes come about through a bit of luck. Face it. You don’t necessarily possess great wisdom, no matter what people may expect.”

At the end of the interviews, we found that there is indeed a rich life after the Nobel Prize—but it isn’t that much different from what came before. Our laureates were charming, surprisingly accessible, and seemingly unconcerned with prestige. They said winning the prize hadn’t changed their relationships with colleagues, family or friends.

“Who wants to be treated like a god?” asks Dehmelt. “It’s too strenuous.”

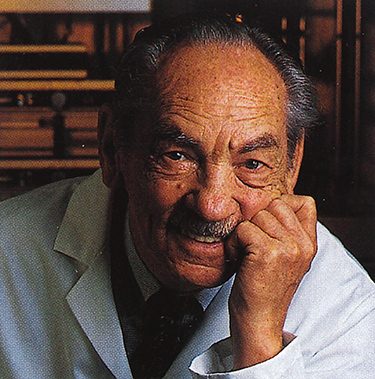

George H. Hitchings

George H. Hitchings, ’27, knew he’d been considered for the Nobel Prize in medicine. He’d already received many other awards for his basic research on designing drugs, which led to the development of medications for various cancers and bacterial infections, as well as AIDS, herpes, gout, malaria and transplantation.

George H. Hitchings, ’27, knew he’d been considered for the Nobel Prize in medicine. He’d already received many other awards for his basic research on designing drugs, which led to the development of medications for various cancers and bacterial infections, as well as AIDS, herpes, gout, malaria and transplantation.

Still, he was surprised when he won. At 83, he thought he was too old to be considered anymore, though he was still hard at work in science and philanthropy, as president of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund in Research Triangle Park, N.C.

His only regret was that his first wife could not be by his side when he accepted the prize. Beverly Reimer Hitchings died in 1985, after 52 years of marriage.

His second wife, physician Joyce Shaver Hitchings, shared Hitchings’ story, as he is now blind, has Alzheimer’s disease, and could not be interviewed. “He’s still enjoying family, old friends, music. The physical beauty of Nature has become more vivid,” she says. “We live near a lake, which reminds him of Puget Sound and Friday Harbor, where he did research.”

In September 1988, shortly before the prize announcement, Hitchings had started a whirlwind courtship with Joyce Shaver, 26 years his junior. When the prize was announced the next month, she recalled, “My first thought was, `Oh no, I’ve lost him to the world.’ ”

But in a few weeks, on Halloween, he asked her to marry him. “Actually, he announced, `Incidentally, you’re my fiancée now,’ while I was driving him to an event in the pouring rain.”

They were married in February 1989, after attending the award ceremonies in Stockholm, together with Hitchings’ family and with a man whose multiple myeloma had been treated by a drug that Hitchings developed.

“On the day he received the prize, he said, `The real gift is not the prize itself, but the individual people who his medicines had helped,” says Mrs. Hitchings.

Hitchings gave all of his prize money to the Triangle Community Foundation, which he founded in 1983. The foundation funds services in the Research Triangle Park area that wouldn’t be provided otherwise, including health care for the poor, sending disadvantaged children to camp, and protecting battered women.

Hitchings’ father, a shipbuilder and community leader in Hoquiam, died when Hitchings was only 12, after an illness that sparked Hitchings’ interest in medicine. When Hitchings was salutatorian at Seattle’s Franklin High School, his teacher gave him a biography of Louis Pasteur, who became a role model as a humanitarian as well as a scientist.

After winning the prize, Hitchings continued to travel and lecture often, as he had for many years. In his lectures, he always showed his favorite slide: a beautiful young Pakistani woman in her wedding dress. Her life had been saved when her infant infection responded to a free sample of an antibiotic that Hitchings had developed and that a Burroughs Wellcome salesman had happened to leave with her doctor.

Hans G. Dehmelt

Hans G. Dehmelt says he “felt like dancing” when he heard that he’d won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1989. But the German-born American citizen was not surprised: “I’d been expecting it, because there were rumors that I was being considered.”

Hans G. Dehmelt says he “felt like dancing” when he heard that he’d won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1989. But the German-born American citizen was not surprised: “I’d been expecting it, because there were rumors that I was being considered.”

Dehmelt was honored for trapping a single electron as well as for isolating a single atom and watching it make quantum leaps. Due to Dehmelt’s discovery, physicists had to revise their estimate of the size of an electron by a factor of 10,000.

Accepting the prize was “wonderful,” he says. “The physicists walked first into the Great Hall in Stockholm’s Town Hall, as decreed by Nobel himself, and as befits the position of physics as the queen of the sciences.” Then came chemistry, then physiology or medicine, then economics, then literature. (The Nobel Peace Prize is awarded in Oslo.)

Since winning the prize, Dehmelt says ebulliently, “My life is now a bed of roses, an absolute bed of roses.” He married his second wife after receiving the prize, but he had known her beforehand.

Dehmelt is still active in his laboratory, and his research interests haven’t changed their direction: “At my age, one is happy to stick to the tack one has chosen earlier,” he says. “But the longer you follow the same tack, the more difficult it gets, and the smaller the return. Still, not many other people study single electrons.”

Long-lost acquaintances and strangers alike have approached him since the award. “But I’m never feeling bothered by that,” he says. “It’s just part of the price.”

Because he shared the prize with two other physicists, Dehmelt says, “It really wasn’t all that much money.” And how did he spend it? “Because the prize money was taxed as `gambler’s winnings,’ I spent it in the appropriate fashion,” he says with a twinkle in his eyes.

E. Donnall Thomas

E. Donnall Thomas never expected to win the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine. The prize usually goes to scientists doing basic research with test tubes, not doctors doing hands-on clinical research with patients.

E. Donnall Thomas never expected to win the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine. The prize usually goes to scientists doing basic research with test tubes, not doctors doing hands-on clinical research with patients.

As a member of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and a professor of medicine at the UW, he pioneered bone marrow transplantation. In 1956 he was the first to show that marrow could be safely infused into a human patient. Later he was the first to treat acute leukemia patients with marrow transplantation.

When the phone rang at 2 a.m. in October 1990, he thought “a fellow at the `Hutch’ was playing a practical joke on me.”

Eventually, though, the reporter from New York convinced Thomas that he’d won the prize and got him to answer a slew of questions about bone marrow transplantation.

“When he hung up, I really lit into him,” says Dottie Thomas, his wife and lab technician “since the beginning of time” (her words). “I said, `What are you doing, giving an interview at 2 a.m.?’ ”

He replied: “Well, this reporter said I won the Nobel Prize.”

Dottie Thomas was so tired, she said, “That’s nice,” and pulled the covers up over her head to try to go back to sleep.

A second later, she sat up and shouted, “What?”

Then the phone started ringing off the hook. NBC News called from New York, arranging a live interview with both Thomas and his co-winner, organ transplant surgeon Joseph E. Murray of Harvard Medical School. “But because the phone kept ringing, we couldn’t call them back for the conference call,” says Thomas, in a Texas drawl laced with dry humor.

Eventually, lights flashing, sirens blaring, the Bellevue police showed up at the door, saying NBC News had called them from New York to find out why Thomas hadn’t called back. Eventually he was connected to New York and made the interview.

For the trip to Stockholm, the Thomases invited not only their three children but also several colleagues from the “Hutch” and their spouses. “It was a lovely time,” says Thomas. He gave his prize money to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, refusing to earmark it for any particular use.

At the center Thomas has stepped down from his administrative duties. But he still does research and consulting, and serves as a mentor. He chooses to speak in his field, at conferences on hematology and oncology, rather than giving more general commencement-style addresses.

Along with “nice letters from former patients and colleagues,” Thomas says, the prize announcement also spurred “odd letters, including appeals for money” and come-ons from car salesmen and real estate agents.

Strangers weren’t shy about sharing their notions about what’s suitable for Nobel laureates. Once reporter sniffed at Dottie Thomas’ 13-year-old, red Datsun pickup truck and said, “I hope you’ll get a better car now.”

In another post-Nobel scene worthy of the Theater of the Absurd, a reporter at a press conference asked Thomas, “When will you be able to do a brain transplant?”—as if his work had logically been moving in that direction all along.

“‘Tell her she needs one,’ Dottie whispered in my ear,” recalls Thomas. “But I answered it straight, and just said bone marrow had nothing to do with the brain.”

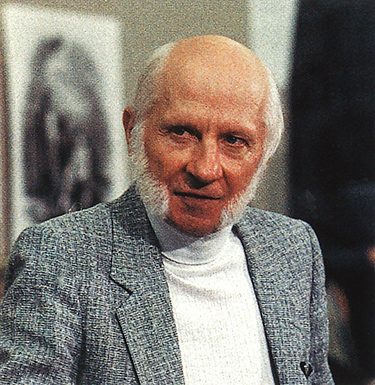

Edwin G. Krebs

Edwin G. Krebs is a soft-spoken, understated Midwesterner, but there’s one thing that gets his goat. Since he turned his attention from medicine to biochemistry, people have been asking him about “his” cycle. They confuse him with Sir H.A. Krebs, the British scientist who won the Nobel Prize in 1953 for elucidating the metabolic Krebs (or tricarboxylic acid) cycle.

Edwin G. Krebs is a soft-spoken, understated Midwesterner, but there’s one thing that gets his goat. Since he turned his attention from medicine to biochemistry, people have been asking him about “his” cycle. They confuse him with Sir H.A. Krebs, the British scientist who won the Nobel Prize in 1953 for elucidating the metabolic Krebs (or tricarboxylic acid) cycle.

One person who made this mistake was the chairman of a clinical department at the UW School of Medicine in 1948, when Krebs started as an assistant professor of biochemistry.

“I must confess that I didn’t correct his wrong impression,” says Krebs. “I was so uneasy about my status then that I enjoyed being treated with such deference, even for the wrong reason.”

In 1992, Krebs and Edmond H. Fischer were awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for figuring out how reversible phosphorylation works as a switch to activate proteins and regulate various cellular processes.

Their discovery was a key to unlocking how glycogen in the body breaks down into glucose. It fostered techniques that prevent the body from rejecting transplanted organs. Their breakthrough also opened new doors for research into cancer, blood pressure, inflammatory reactions and brain signals.

“One of the things that went through my mind when we won was that I wouldn’t have to answer that cycle question again,” says Krebs. “But people still congratulate me for having `my’ cycle recognized—and think it took till 1992 for that to happen.”

It took till three days after the prize was announced for Krebs to think of asking about how much money would be involved.

“Ed and I invited our extended families and paid the way for those who needed it,” he says of the Stockholm ceremonies. Krebs and Fischer donated the remaining money to educational, medical and arts institutions, including “a little” to the UW biochemistry and pharmacology departments. “Easy come, easy go,” says Krebs.

Looking at the world today, Krebs is disappointed that the goal of becoming a scientist—or even of getting an education—is becoming less accessible to poor children: “I would like to see a day when any kid would be able to go as far as his abilities could carry him,” he says. “In many ways, the situation for young people seems worse now than when I graduated.”

As UW professor emeritus and Howard Hughes Medical Institute senior investigator emeritus, Krebs still leads an active lab. But it’s down from 20 to five lab people, who are all now looking elsewhere. “I hope to close my lab in a year,” he says.

Edmond H. Fischer

Edmond H. Fischer says winning the prize can be “a bizarre business that catches you off guard.

Edmond H. Fischer says winning the prize can be “a bizarre business that catches you off guard.

“The first question is: `Why us?’ There are so many brilliant people working, including ones we’ve recommended.” For a decade, he and Krebs had been among the thousand scientists asked to submit nominations for the prize.

“If you get a gold medal in the Olympics, you know why. You came out first,” he says. “In science, it’s so different. You do your thing, working without thinking about this or any other award. Then all of the sudden in the middle of the night you get a call.”

That’s how it happened for Fischer. He’d just returned from a trip to Italy in October 1992, when the telephone rang in the dark and woke him from a deep, jet-lagged sleep. An unfamiliar voice asked, “Are you Dr. Fischer?”

“My first thought was, `Who is this guy? Does he want to sell me stocks, or replace the gutters on the house?’ ”

“Are you Dr. Fischer from the University of Washington medical school?” the voice asked. ” `Yeah,’ I said. `Whaddya want?’ `Congratulations,’ said the voice. `This is CBS in New York. You’ve just won the Nobel Prize, along with Dr. Edwin Krebs.’

“At first I didn’t believe it,” says Fischer. “But the moment he mentioned Ed, I woke up. I put the lights on. It was 3:45 a.m. As soon as I put the phone down, it rang again.”

Finally the phone stopped ringing for a second, so Fischer could wake his wife, Beverly, who was ill and had taken a sleeping pill. “She was totally zonked, and just said, `Oh.’ ”

At 5 a.m., Fischer called his longtime secretary, Carmen Westwater, to suggest that she watch the 6 a.m. news on television. “Something happened that’s going to cause you lots of work,” Fischer said.

“Don’t tell me,” she replied. “I know. You lost all your plane tickets. Again.”

Born in Shanghai, China, and educated in Switzerland, Fischer was a Swiss national before becoming a U.S. citizen. A courtly gentleman, the UW professor emeritus of biochemistry recently closed his lab but still works in his office every day.

Fischer recalls the trip to Stockholm with family and friends with special fondness. “We all stayed in the Grand Hotel, overlooking the bay. Ed and I had been good friends, but after that week, we felt like family. It was a family affair, very warm,” says Fischer.

The Nobel week of dinners, balls, ceremonies, concerts and exhibits was a “beautiful experience,” he says. “It felt like floating. After being treated like a king, you want to isolate yourself to come back to Earth.”

Not long after, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, which had supported their research, asked Fischer and Krebs to appear on a show to thank the television stations that had carried the famous MDA telethon hosted by Jerry Lewis.

“We were expected to follow an absurd TelePrompTer script about how we’d been striving for the prize—which of course we hadn’t ever done,” says Fischer.

Some other scientists were there, and they were following their scripts. But Fischer and Krebs decided they couldn’t. Instead, they filled their minutes of airtime with their own thoughts.

“‘How has your life changed since the Nobel Prize?’ they asked us. We said, `Here’s how: You see that limo waiting for us downstairs? Two years ago, it would have been a Yellow Cab instead.’”

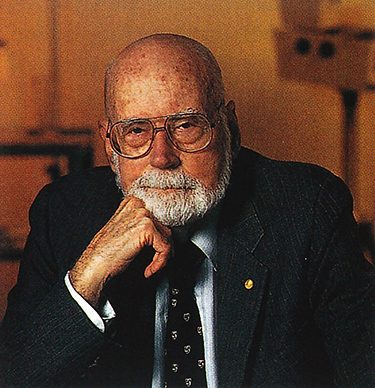

Martin Rodbell

Martin Rodbell and his wife, Barbara, were visiting their daughter in Bethesda, Md., when the phone rang at 6 a.m. one October day in 1994. His daughter was reluctant to wake him, but eventually she did, saying, “Someone with a foreign accent wants to speak with Dr. Rodbell.”

Martin Rodbell and his wife, Barbara, were visiting their daughter in Bethesda, Md., when the phone rang at 6 a.m. one October day in 1994. His daughter was reluctant to wake him, but eventually she did, saying, “Someone with a foreign accent wants to speak with Dr. Rodbell.”

Rodbell hadn’t expected to win the Nobel Prize. “No one should expect such an honor, given the large number of people equally eligible for it,” he says.

“Still, as soon as I heard the Swedish accent, I realized something was afoot,” Rodbell recalls.

“The voice declared that I had won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine and then asked: `Do you accept?’

“The only thought in my mind was, `Do you think I should accept?’ followed by a voice saying, `I think you should.’

“Finally I said, `OK, I accept,’ and thus ended our conversation. What followed was bedlam.”

Now scientist emeritus at the National Institute of Environment Health Sciences, located in North Carolina’s “Research Triangle,” Rodbell earned his Ph.D. in biochemistry at the UW in 1954.

He was honored for his contributions in discovering the role of GTP (guanosine triphosphate) in signal transduction, which helps cells respond to hormones. Aberrations in signal transduction can lead to diseases such as cholera and even some kinds of cancer.

He still does research along similar lines. “But I do much more reading and writing, because there is time available and fewer distractions,” he says, since he no longer serves as an administrator.

Thanks to the prize money, he was able to shore up his “rather small” retirement income and to help his four children and seven grandchildren.

Rodbell tends to shy away from radio and television interviews. But he enjoys speaking to audiences, especially of younger students, about the value of funding and conducting basic scientific research. He feels strongly that young people should get the message that they can muster what it takes to do science: They don’t have to be privileged or extraordinary individuals to make important scientific contributions.