It begins with a dreamer It begins with a dreamer It begins with a dreamer

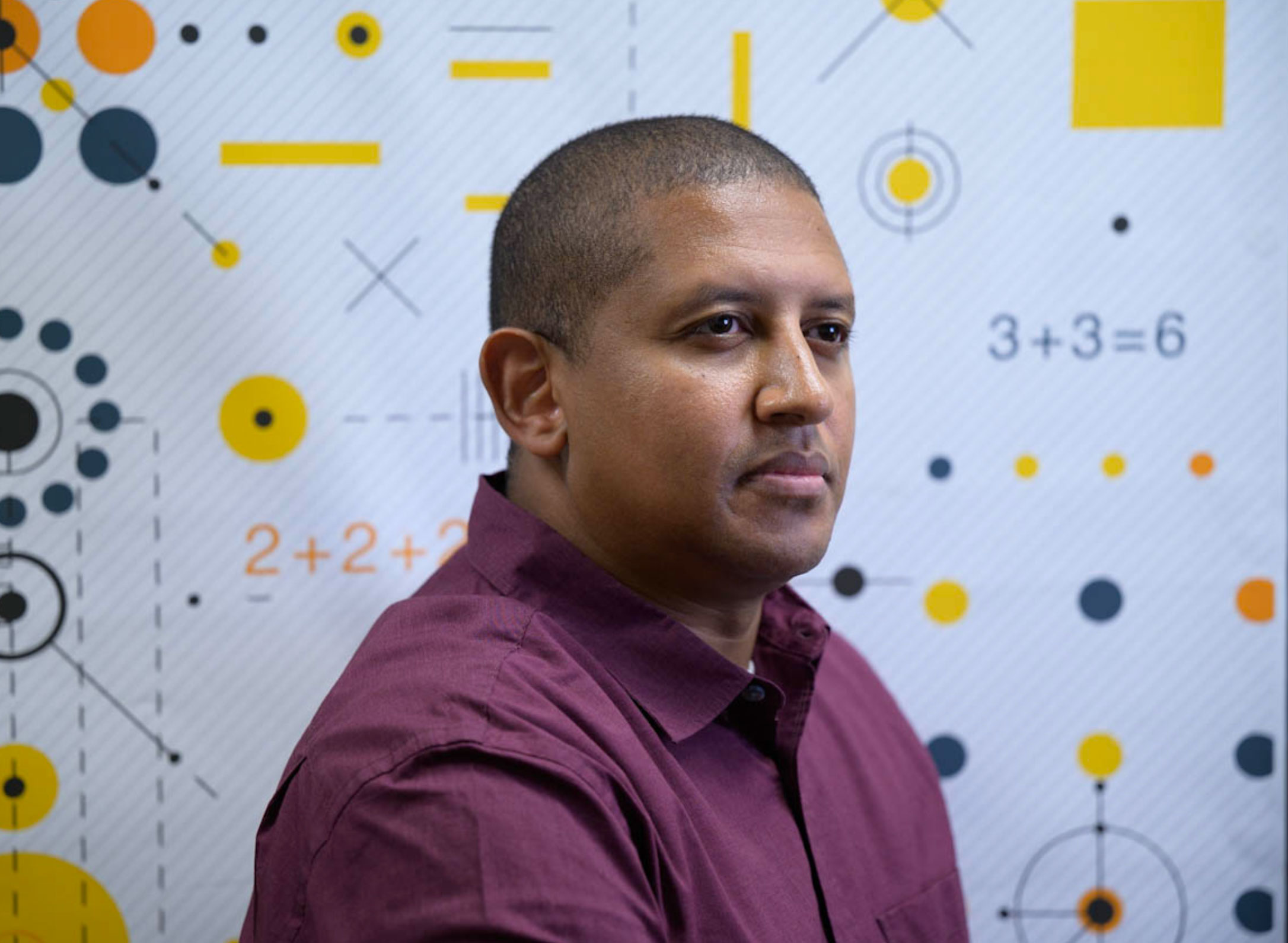

Alula Asfaw is out to change education

By Hannelore Suderman | Photos by Malinda Hartong | September 2022

Alula Asfaw dreams big. As a student at the UW, he was stunned by the good luck and support he received getting into college. His dream, then, was to open the way for other students like him who might not realize that going to college was a possibility.

After graduating in 2008 with degrees in English and political science, he dreamt of going into public service and education, and he landed a job in Washington, D.C., working in the Department of Education’s Office of Innovation and Improvement. In that role, he supported place-based initiatives to improve schooling in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.

After that, he attended the University of Cambridge to pursue a master’s degree in politics, development and democratic education. There, and at Yale Law School, he dreamt of using his experience, including his new legal expertise, to spark profound change in the American educational system. So, about six years ago, he created a program to help disadvantaged schoolchildren—and possibly change the paradigm of education.

In 2016, Asfaw founded Bonds of Union, a nonprofit educational organization that aims to help the highest-need students by giving them a learning coach who not only focuses on their math skills, but also their social-emotional skills and critical thinking. Today, the nonprofit’s pilot project, called Ascend, is wrapping up at Bond Hill Academy, a public elementary school in Cincinnati, Ohio. The students who took part showed a marked improvement in their test scores, much higher than their classmates, says Asfaw, who had moved to Cincinnati to run the nonprofit. “Math was the vehicle for us to teach them to be lifelong learners,” he says.

Asfaw knows the challenges struggling schoolchildren face. He had several different homes as a child. His family immigrated from Ethiopia, bringing Alula to the United States when he was 2 months old. After moving between the two countries, Asfaw returned permanently to the U.S. at age 6. When he started the sixth grade, his mother went home to East Africa and he stayed behind. He moved in with his older brothers—three had settled in the Seattle area—living with different siblings at different times.

“There are a lot of talented, smart, capable kids who are coming up short.”

“My path to the University of Washington was a lot of just stupid luck,” he says. “I’d been recommended by a teacher at Cleveland High School to sign up for this program called Upward Bound. If they had caught me at a different day or a different time, I probably wouldn’t have done it.”

The federally funded program provides potential first-generation college students and students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds with tutoring and advising to prepare them for college. It operates in just a few Seattle-area high schools. When Asfaw changed schools, he was no longer eligible for the program. Nonetheless, director Leny Valerio-Buford “fought hard to make sure there was an exception for me to remain,” he says. “I credit her a lot for supporting me and getting me into the University of Washington.”

Though the college-readiness program brought Asfaw to the UW campus for events a few times, when he arrived as a freshman, he felt both out of his depth and incredibly fortunate. “I could have easily not been here,” he says. “And others of my classmates who were much smarter than I was did not make it here.”

Some of his new friends came from more privileged backgrounds, and while they were very positive with him, “they were profoundly disconnected from appreciating the plight and path and kind of life circumstances of people like me,” he says. Asfaw was caught between his new life and the old. “I did have that feeling of guilt, questions around fairness that were just hard to ignore,” he says.

Wondering how he could leverage what he had at the UW to benefit future students, he and a few friends came up with an outreach program that would put UW students to work helping high schoolers make it to college. “There are a lot of people who don’t know how to navigate this process of applying to college,” Asfaw says. “And there are a lot of talented, smart, capable kids who are coming up short, not because of their skills or grades or test scores, but because they’re just not navigating well.”

Alula Asfaw ran a pilot project that provided learning skills and confidence to children at Bond Hill Academy, a public elementary school in Cincinnati.

Then he met Stan Chernicoff, a UW geology professor who had created a nighttime study center for undergraduates in Mary Gates Hall. Chernicoff was impressed with the freshman’s ideas and energy. “Rarely would a day go by when he didn’t show up in my office,” he says. “He wanted to share things that interested him. He just didn’t believe things couldn’t be done.”

Asfaw was also sharing his ideas with his classmates. One evening over chili cheese fries at Schultzy’s, a group of them were swept up for hours in conversation about how some high schoolers were finding their way to college through federal and UW outreach programs, but others at different high schools were not. They thought it was arbitrary. “We were angry, and we wanted the UW to do something,” says Jenée Myers Twitchell, ’04, ’09, ’17, a co-founder and later director of the project that grew out of that discussion.

With help from faculty including Chernicoff and Ed Taylor, ’93, dean of undergraduate academic affairs, Asfaw, Myers Twitchell and three other students developed a plan to send UW undergraduates to middle and high schools to help students overcome barriers to college. Under the Dream Project, UW interns could attend classes about educational equity and participate in outreach, and many would come away with a greater understanding about the complexities and challenges facing low-income and first-generation students.

Today, the Dream Project is going strong. This year there are plans to send 33 students to 37 Puget Sound-area schools. Since its start, hundreds of UW student-mentors have helped thousands of teens find their way to the UW and other schools.

Whether in Seattle or Cincinnati, Asfaw has always focused on improving access to education and breaking through systemic limitations. He expanded his efforts to explore curriculum, instruction and even the school’s physical design. His goals are not just to help children with academics, but with social and emotional growth as well.

“Of course, this is bold and arrogant to think that one guy and his team can change the paradigm,” Chernicoff says. “But they may be on to something in terms of solving problems. If we’re going to make education better, it takes thinkers and doers—people like Alula.”