The summer of 1948 should have been an easy time for UW Professors Herbert Phillips, Joe Butterworth and Ralph Gundlach. The academic year was over, and teaching summer school was never that stressful for faculty members—especially those with more than 20 years experience. But in June, these three men had received subpoenas from the state's Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities. In July they were to appear at public hearings in the Seattle Field Artillery Armory.

The committee—chaired by Rep. Albert Canwell, a Spokane Republican (pictured, holding a note card, surrounded by committee members)—was created by House Concurrent Resolution No. 10, which stated, “the committee shall investigate the activities of groups and organizations whose membership includes persons who are Communists, or any other organization known or suspected to be dominated or controlled by a foreign power.”

The focus of the July hearings was the University of Washington.

Phillips no doubt knew why he had been subpoenaed. A teacher of philosophy, he always warned his students to watch out for a Marxist bias in his opinions. He had taught at the UW since 1920 and had tenure, even though his title was assistant professor. Butterworth said nothing about his political views in the classroom, but then, the subject rarely came up in the study of Chaucer and Old English. After earning a master’s degree at Brown University, Butterworth had taught at several schools and enrolled in the UW’s doctoral program, but had never earned his Ph.D. Still, he had been on the faculty as an “associate” since 1929, and he too had tenure.

Gundlach chafed at his subpoena. As a social psychologist, he was passionate about applying his psychological knowledge to real world problems, and had been among the earliest members of the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues. He had also supported a long list of liberal causes and organizations, but the Communist Party, he told friends, was not among them. On the faculty since 1927, he was an associate professor with tenure. Now, with the hearings approaching, he wrote to several of his colleagues:

“The strategy of the Canwell Committee is really to split the faculty into various groups and classes; and likewise to split up those who have been subpoenaed so that a number of persons may be fired, to the great relief of those challenged but missed but who can then thankfully fight a losing battle for those discharged.”

His words proved prophetic. In October, Phillips, Butterworth and Gundlach—together with several of their colleagues—were brought before the tenure committee of the Faculty Senate. In January, 1949, all three were summarily dismissed. None ever worked in academia again.

“It was hitting hard at the heart of what the people wanted in education and wanted for their sons and daughters. So, there was constant pressure on legislators to get with it and do something.”

Albert Canwell

Fifty years have passed since the hearings that cost these men their jobs. Not an anniversary to celebrate, but the University will mark it with a reconsideration of the period in which these events took place. The “All Powers Project,” an interdisciplinary effort including speeches, panel discussions and even a dramatic recreation of the hearings will give today’s citizens a chance to understand what happened and some of the reasons why.

The hearings in Washington were not a sudden aberration. Although the Communist Party was legal and had attracted followers who admired its economic policy and its stand against fascism in the ’30s, its image was clouded. Many who joined it felt the need for secrecy. There was reason for their concern; “un-American activities” investigations had been pursued in other states and in Congress. After World War II, this trend intensified. According to Ellen Schrecker, historian and author of No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities, the 1947 initiation of President Truman’s loyalty-security program for federal employees established anti-communism as the nation’s “official ideology.”

In Washington, the 1946 elections featured some Republicans campaigning against “Communist-controlled Democrats,” by which they meant legislators who had supported organizations alleged to be “Communist fronts.” The Republicans triumphed, gaining control of both houses of the Legislature. Among those swept into office on the tide of change was Canwell, who claims in his recently-published oral history that he had not sought the office and campaigned little. “I made two statements about what I would do,” he told his interviewer. “I wouldn’t vote for any new taxes and I’d do something about the Communists.”

What he did was to introduce House Concurrent Resolution No. 10, which was modeled on similar legislation in other states. When the resolution passed and committee members were appointed, there were five Republicans and two Democrats. Named chairman, Canwell immediately launched his first assault—on the Washington Pension Union—holding hearings in January of 1948. The UW was his next target.

Canwell knew he had political backing for singling out the University. After the election, conservative Democrats had joined Republicans in a caucus and had produced a report stating, “It is common knowledge in many quarters that the Communists have infiltrated the University of Washington campus and that their supporters have found important places on the faculty.”

Canwell himself claims the University “had become not only a local but a national scandal. It was hitting hard at the heart of what the people wanted in education and wanted for their sons and daughters. So, there was constant pressure on legislators to get with it and do something.”

But as the committee began its investigation, one of Canwell’s Democratic committee members made a tactical error. In a speech in Spokane, Sen. Thomas Bienz claimed there were “probably not less than 150 Communists or Communist sympathizers on the faculty.” Knowing this kind of claim could backfire, Canwell quickly announced that the committee was not ready to say exactly how many faculty were Communists.

The publicity, however, made an already nervous campus more so, as Canwell’s staff of investigators began knocking on the doors of the UW faculty. Philosophy Professor Melvin Rader later wrote about his experience with them: “It was the middle of May in the year 1948. I was hard at work in my office in Savery Hall. … There was a knock on my door. When I opened it I recognized two of the investigators of the Committee on Un-American Activities of the state Legislature. … They talked to me about an hour. `Our information,’ they said, `puts you in the center of the Communist conspiracy.’ ”

Though many on campus resented the investigators’ methods, they were advised to cooperate. At an all-campus meeting, President Raymond Allen told the faculty, “We cannot afford to engage in a public fight with the Canwell Committee.”

Raymond Allen

Jane Sanders, ’71, ’76, who did her doctoral dissertation and later a book (Cold War on the Campus) about the UW during this period, believes Allen felt trapped between “the legislative committee, public opinion and the regents on one hand, and the faculty and the American Association of University Professors on the other.” Allen had been unsuccessful in getting the regents to endorse either a tenure bill in the Legislature or the tenure provisions in the Faculty Code. With these failures, he knew he and the faculty served at the pleasure of the regents. Moreover, as a physician and former medical dean, he had been recruited to the UW in 1946 to nurture the fledgling medical school created by legislation the year before. He needed a good relationship with the Legislature to accomplish this. Publicly, Allen stated that he “welcomed” the investigation.

In June, Canwell gave Allen a list of 40 faculty members who would be subpoenaed to the hearings. He said he wouldn’t release the names to the press since some were considered friendly witnesses. Interviewed by the Seattle Times, he said “We have a fine University here, but the faculty members who are Communists are not representative of this state or of the principles of academic freedom.”

The hearings were held on the second floor of the armory, now the Center House of Seattle Center. English Professor Joseph Harrison later described the scene: “Six or seven men sit behind a high table, the man in the center armed with a gavel. Below them, facing a witness, sits the chief inquisitor. Behind him sit two or three rows of members of the faculty. Beyond them sit 91 spectators, all that can crowd into the small chamber.”

The five days of hearings followed a format used in other investigations. Ex-Communists on the national scene were brought in to give “expert” testimony on the nature of the Communist Party, which was portrayed as unlike other American political parties. Party leaders, the witnesses said, expected strict adherence to positions handed down from Moscow and advocated the overthrow of the U.S. government by force and violence. Local ex-Communists followed the “experts” to the stand and reported seeing professors at meetings of the Communist Party.

In the end only 11 professors actually testified although, curiously, Canwell also used the hearings to make accusations against some people who had no affiliation with the University. Burton and Florence James, for example, had taught at the UW in the past but at the time of the hearings had their own theater company which performed in what is now the Playhouse Theatre on the Ave. Both were accused by witnesses of being members of the Communist Party.

The professors who testified had mixed reactions to the questions. English Professor Sophus Winther said he had been a member of the party for a year and named colleagues who had been in meetings with him. English Professors Maude Beal, Angelo Pellegrini, Harold Eby and Garland Ethel, and Anthropology Professor Melville Jacobs admitted past party membership but would not name anyone else. Rader and Sociology Professor Joseph Cohen denied ever being members of the party. Phillips, Butterworth and Gundlach refused to answer the questions at all.

Gundlach stated the basis for the trio’s refusal most clearly, saying—when asked if he was a member of the Communist Party: “No legislative committee has the right to ask about one’s personal beliefs and associations.” Unfortunately, the courts of the time disagreed with him. When witnesses in a similar hearing challenged this right in 1947, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case, thus sustaining two lower court rulings that investigative committees did not violate the First Amendment by asking suspected Communists about their political activities.

Knowing they had court support, the committee demanded a response of “yes” or “no” to the question of Communist Party membership. Those who refused to answer were cited for contempt, and sometimes treated with contempt. When Ethel refused to name associates in the party, he quoted Polonius’ speech to his son in Hamlet, “To thine own self be true.” He then explained, “Now that happens to be my situation; I have a standard of honor, and that standard is not to name other persons, and I told you that would be my position.” Thereafter, Ethel was referred to as “Professor Polonius.”

Canwell made a great show of allowing all those testifying to have attorneys present, but the attorneys were hamstrung. They were not permitted to raise any objections to the proceedings, to cross-examine witnesses who had accused their clients or to offer evidence in their clients’ behalf. When they tried to speak, Canwell banged his gavel and interrupted, as in this comment addressed to Phillips’ attorney John Caughlan:

“We are not going to debate the issue of the legality of this committee or its processes. That may be done elsewhere; and at present, you will be confined to the instructions given, and from here on in we will expect you to comply precisely with those instructions.”

When Caughlan responded by asking a question, Canwell said, “You will ask no more questions. We are not going to go on with any ridiculous procedure here. You will either comply with the instructions of the committee or you will be removed . . . .”

This was no idle threat. State Patrol officers were posted at the hearings, and on Canwell’s orders, they ejected anyone who spoke out. He also dispatched the officers outside the armory when protesters calling “Canwell must go!” were heard in the hearing room.

Florence Bean James, co-founder of the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, confronts the committee after a witness accused James and her husband of being Communists. James was escorted out of the hearing room by state patrolmen. Photo courtesy of Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry.

It must have been difficult for the accused professors to listen to testimony about their alleged activities and not be able to reply. Florence James at one point became so angry that she stood up and shouted at the committee, whereupon she was “escorted” out of the room by State Patrol officers. Rader managed to keep his composure when one of the “expert” witnesses said he had seen the professor at a Communist school in New York during a summer Rader knew he had spent in Washington state. He decided to save his anger and seek a legal remedy later.

When the hearings were over, the University was left with charges of communism among its faculty and the question of what to do. Could Allen have chosen not to act on the information from the hearings? Sanders thinks not. The regents had publicly indicated their intention to proceed if Allen didn’t. Regent Joseph Drumheller had even stated at one point that he knew there was “subversive activity” on the campus. Rather than defy the committee and his bosses, Allen responded to faculty pleas for sovereignty in the matter. He named a faculty committee to determine who would face dismissal, promising that those charged would receive a hearing before the Faculty Senate’s Committee on Tenure and Academic Freedom.

Those considered uncooperative at the Canwell hearings paid the price. The committee decided to charge Phillips, Butterworth and Gundlach, who had refused to testify, as well as Eby, Ethel and Jacobs, who had admitted past membership in the Communist Party but had refused to name others.

Communist Party membership was not grounds for dismissal in the University’s tenure code, but the administration tried to claim the “good behavior” and “efficient and competent service” called for in the code could be interpreted broadly by the committee. Accordingly, their only charge against Phillips and Butterworth was that they were members of the Communist Party. To this charge against Gundlach, they added others revolving around his alleged dishonesty with Allen early in the investigation (He said “No one can prove I’m a Communist, and I cannot prove that I am not.”). Eby, Ethel and Jacobs were similarly charged with dishonesty, based on their initial denial of their past membership on the advice of their lawyers. The six-week-long hearings, during which the professors were accorded the right to present their own cases, were closed to the public.

From left, Professor Ralph Gundlach, attorney John Caughlan, and state Communist Party Secretary Clayton van Lydegraf wait for the regents to rule on Gundlach’s case. The regents voted to fire Gundlach. Photo courtesy of Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry.

The outcome of the hearings was not what the administration had hoped for. The committee was unanimous only in recommending that Eby, Ethel and Jacobs not be dismissed. It voted 8 to 3 against firing Phillips and Butterworth, despite their open admission that they were members of the Communist Party, rejecting the administration’s plea for a broad interpretation of the tenure code. And it recommended dismissal of Gundlach by a 7 to 4 vote, mainly on the basis of what members saw as his dishonesty with Allen.

In his advice to the regents, Allen chose to overrule the committee. He agreed with the recommendation to dismiss Gundlach but also advised that Phillips and Butterworth be fired. He went along with the committee on the other three. Why did Allen take such a hard line? Sanders believes he knew that some people would have to be fired to satisfy the Legislature, and that one would probably not be enough. The fact that Phillips and Butterworth had admitted party membership and that they and Gundlach had refused to answer the Canwell Committee’s questions, made them easy targets.

Although rumors circulated that some of the regents wanted to fire all six professors, in the end they followed Allen’s recommendations. Their judgment was handed down Jan. 22, 1948; Phillips, Butterworth and Gundlach were taken off the University payroll Feb. 1. Eby, Ethel and Jacobs remained, forced to sign an affidavit that they were not members of the Communist Party and placed on probation for two years.

According to Schrecker, Allen wanted to defend the University from outside intervention and was willing to redefine academic freedom to do it. She writes, “If we define academic freedom in institutional instead of ideological terms, as the preservation of the professional autonomy of the academy, then we can understand why so many people believed it was necessary to anticipate outside pressures and get rid of Communist professors before reactionary politicians. . . took over the task.” Allen rested his case on the idea that strict adherence to the party line meant surrendering intellectual freedom and that the secrecy of the party was the opposite of open inquiry—thus Communists were disqualified from academic life.

The reaction of the UW faculty to the dismissals was mixed. After the regents’ action, 103 professors signed an open letter criticizing the firings as involving guilt by association and saying that what had happened was damaging to the morale of the faculty and the reputation of the University. However, 600 other professors remained silent. Nationally, the firings created strong reactions—both positive and negative—in the popular and the academic press. But there was never a concerted movement to protest the action; even the American Association of University Professors—though it created an investigative committee—never visited the campus and delayed its report until years after the fact.

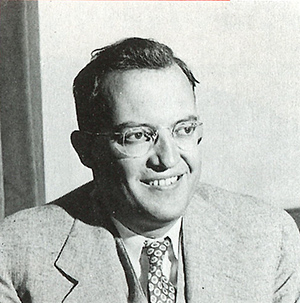

Herbert Phillips

As for the fired professors, they did not go quietly. Phillips and Butterworth set off on lecture tours. Gundlach tried to sue the University for reinstatement, but couldn’t get an attorney to take his case. Professionally, the trio soon found that they were persona non grata.

In 1949, Gundlach was convicted of contempt of the legislative committee, fined $250 and spent 30 days in jail. Though he sought and received endorsements of his work from two professional organizations, he found it didn’t help him get a job. Even when a friend asked him to substitute teach a summer school class at Columbia University’s Teachers College for one week, that university refused to hire him. With the academy closed to him, Gundlach got additional training and worked as a clinical psychologist for the rest of his career. But he never forgave the University. In 1962, when Charles Gates’ history of the UW was published, Gundlach wrote the author a six-page letter disputing his treatment of the Canwell affair. He eventually retired to London and died in 1978.

Phillips was 56 when the hearings took place—too old to easily start a new career and too young to retire. After being fired in 1949, he occasionally was allowed to guest lecture but he never had another job at any university. Later he became a laborer and retired to San Francisco, where he died in 1978.

Joe Butterworth

Butterworth’s case was worse. In a specialized area like Old English, there is no work outside academia, and Butterworth seemed unsuited for other kinds of labor. After he was fired, he could not find any academic position even though he wrote letters to all 2,000 members of the Modern Language Association. He eventually went on public assistance. Described as a “broken man” who haunted Seattle’s Blue Moon Tavern in the ’50s, he died in 1970.

Eby Ethel and Jacobs continued to teach at the University until their retirements. Sanders reports that Jacobs refused to sign anything even remotely political for the rest of his career. He became ill and retired in 1971, dying shortly thereafter. Eby and Ethel both talked about social ostracism in the years following the hearings and about being kept at the low end of the pay scale for their ranks. Eby retired in 1968 and died in 1994. Ethel retired in 1969, but his life ended tragically. In 1980, he shot his wife, her sister and brother-in-law to death before turning the gun on himself.

Rader used the period after the hearings to compile evidence to clear his name. Though the prosecutor’s office filed a perjury charge against his accuser, there was resistance at every turn, and finally the New York court refused to extradite the witness to Washington to stand trial. The Seattle Times then took up the professor’s cause, and reporter Ed Guthman, ’44, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949 for the series of articles that proved Rader’s innocence. Rader continued to teach at the UW, but it was 20 years before he was able to write about his experience in a memoir he called False Witness.

Allen did some lectures after the firings and was quoted in the New York papers, saying the University had fired “three Communists.” Gundlach filed a libel suit against the papers and against Allen, saying it had never been proved that he was a Communist and that, indeed, he wasn’t. The papers agreed to print a retraction and correction.

Allen left the UW in 1951 to become chair of the Psychological Strategy Board, established that year by President Truman to make the country’s psychological warfare program more effective. Truman regarded the board as the nation’s top planning agency in the Cold War. In 1952 he became the first chancellor at UCLA. He left that institution in 1959, serving in U.S. public health programs in Asia and South America. He retired to Virginia in 1967 and died in 1986.

Canwell ran for re-election in 1948 on the basis of his anti-Communist campaign—and lost. He later ran the American Intelligence Service in Spokane, where—according to Rader—he kept files on hundreds of people alleged to have links with Communism. He also published a newsletter called The Vigilante. Today he still lives in the Spokane area and expresses no regrets for his activities in 1948.

Attempts to revive the un-American activities committee in the Legislature after Canwell’s departure were unsuccessful, but the campus climate continued to be testy. In the early 1950s, both literary critic Kenneth Burke and physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer were denied Walker-Ames Professorships because they allegedly had Communist sympathies. And the Legislature later instituted a loyalty oath for all public employees, forcing them to swear that they were not members of any “subversive” organizations.

Within academe, the University’s reputation suffered. According to Charles Gates’ history of the UW, after Canwell “a number of departments on the campus had occasion to discover during the ensuing years the doubtful esteem in which the University of Washington was held at other institutions.”

The UW’s experience with the Canwell Committee also had implications far beyond the Seattle campus. Schrecker believes the Washington case set a precedent that allowed other schools to declare Communists unfit to teach. “The University of Washington case had cleared the way,” she writes. “Once the anti-Communist consensus and the machinery for enforcing it was in place, it was to become all too easy for academic institutions to turn against other types of political undesirables.”

And in the decade following the UW case, that is exactly what happened. Professors found their memberships in organizations and their stands on social issues scrutinized. Often, merely being subpoenaed by an investigative committee was enough to cost someone a job. Promotions were held up; passports permitting participation in international scholarship were denied. Many states, like Washington, instituted loyalty oaths.

The tide turned eventually. But for most who had lost their jobs and their reputations, it was too late. Because of its role in what happened, it was perhaps appropriate that the UW finally issued a public apology—even though only one of the professors charged in 1948 was still alive to hear. The time was January 1994, the occasion a ceremony honoring Harry Bridges, a labor leader who had been accused of communism during the same period. Then-President William Gerberding had this to say:

“My task is to state clearly and unequivocally that the University of Washington was wrong to dismiss Ralph Gundlach and the other two and to have brought into disrepute, or to have participated in bringing into disrepute the other three who were involved. . . . This was a dark day in our history, and we must make sure that it doesn’t happen again. `Make sure’ may be too strong a phrase; there’s nothing anybody can `make sure’ in history. We must do what we can to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

“I don’t wish to be judgmental or pious about this. I don’t know what I would have done had I been there . … Presidents are under some considerable pressure. But whatever the ex post facto justifications or explanations may be, the basic, simple truth is that what happened to those professors … was an outrage. It was a disgrace. It was, in the dictionary sense, not in the perverted sense, un-American.”