Back in the days of disco, Architecture Professor Daniel Streissguth, ’48, was asked to lead the design for a new home for the then College of Architecture and Urban Planning. His brief was to lead the team to create “useful, well-balanced architecture” with offices, classrooms, studios, a library and space for the design disciplines to collaborate. It needed to capture the vibe of the times in raw concrete with its structural components on view.

Working with architect Gene Zema, ’50, and a team that included architecture professors Grant Hildebrand and Claus Seligmann, Streissguth had to synthesize the desires of his colleagues while meeting the expectations of the administration—all in a hip, brutalist-style package. “We hoped to have a building that was open to the community,” Streissguth told an audience at a College of Built Environments presentation in 2015. It was to be “transparent so that individuals working inside and people from outside and inside… could see one another’s activities. … We hoped the building would adapt itself easily to future changes and additions.”

While it has had a few updates, Gould Hall hasn’t substantially changed in the 50 years since students first set foot in it. It has four above-ground floors, cantilevered balconies and rooms with wide windows that peer both inside the building and out to the trees. While outside it sits quietly on its corner, the interior offers a visual thrill as floating staircases crisscross a skylighted atrium.

“One of the most interesting things about Gould is that from the outset it was designed to be expanded and to be open-ended.”

Ken Oshima

Last year, because of the pandemic, Professor Ken Oshima had to scuttle plans to take his studio class to Japan to study metabolic urbanism—how the built environment can be constantly reshaped. So instead of sites around Tokyo, he refocused his students on Gould Hall, their own campus home. “They knew it and could be much more familiar, especially with them meeting virtually, online,” he says.

“One of the most interesting things about Gould is that from the outset it was designed to be expanded and to be open-ended,” Oshima says. “It was not just this museum piece but something to continually rethink.” That rethinking is especially relevant now, he says, since the U District is rapidly transforming with twenty-story apartment buildings and a light rail station that opens in September.

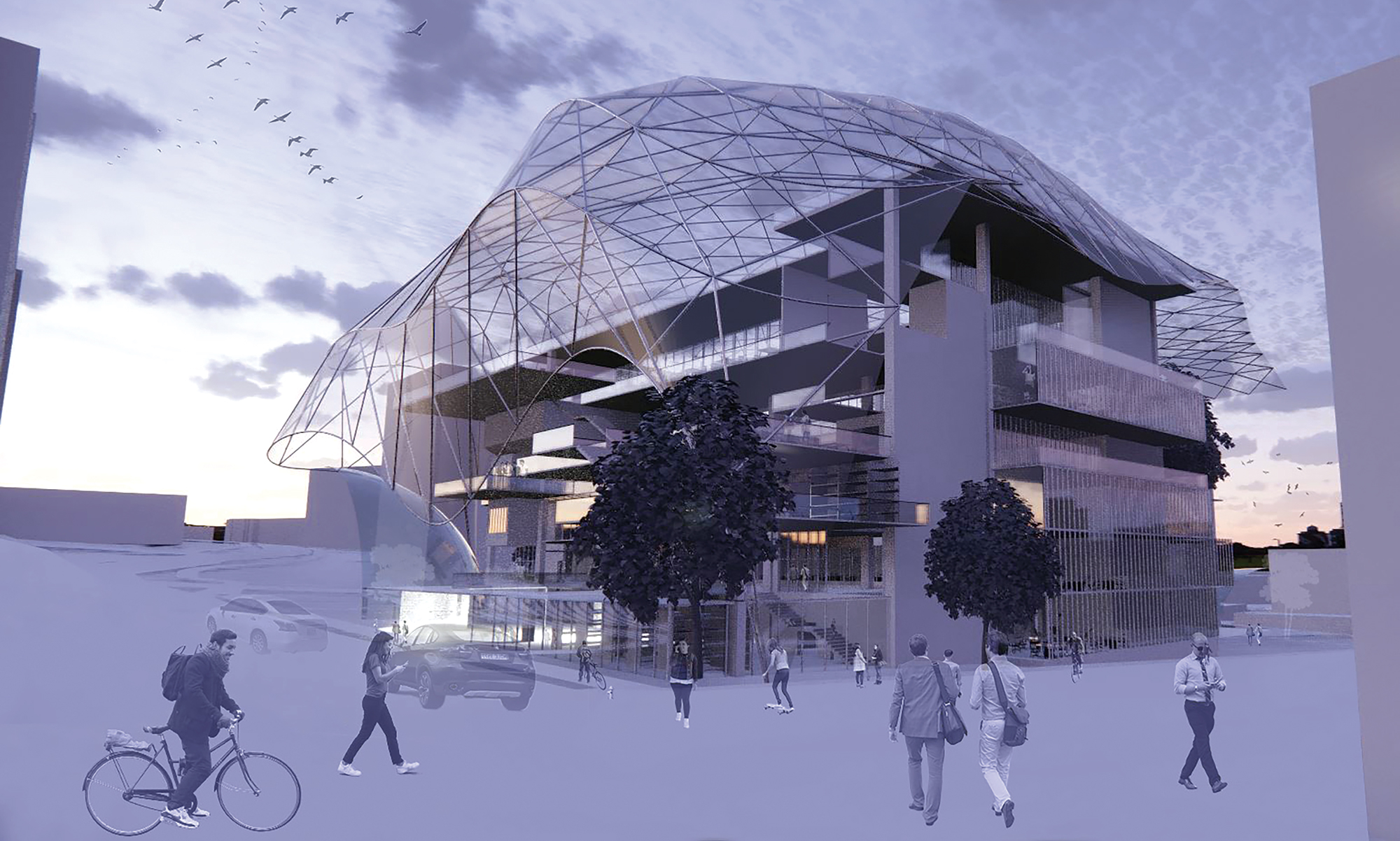

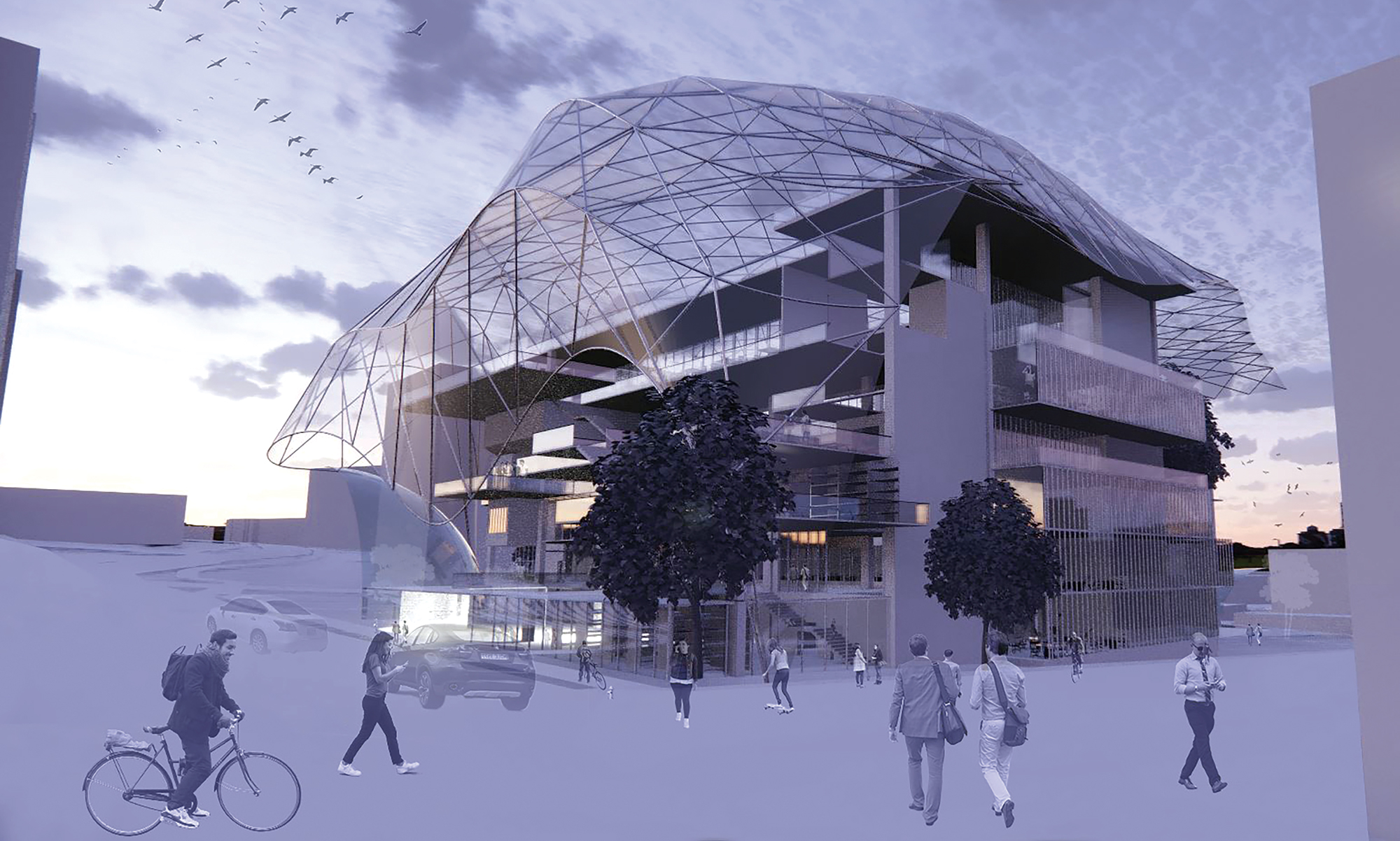

Oshima’s students looked at the original vision of Streissguth’s team and then gazed into the future to see how the building might evolve over the next few decades. Some designed rooftop terraces and covered plazas. Others, gardens and a cinema. They added stories, capturing new views across campus and toward downtown. They added windows, exterior staircases and open-air construction spaces. Miggi Wu added hydroponic ponds to a terrace. Zining Cheng opened classrooms to the sky and wrapped the building in a massive transparent membrane.

These explorations would have pleased Streissguth, who died at the age of 96 in November. As where and how we work evolves amid the pandemic, so should Gould Hall. “It’s a really great time for people to be reimagining their own environment,” says Oshima.