Under

the spell

of Astra

Under

the spell

of Astra

Under

the spell

of Astra

Visionary UW architecture professor Astra Zarina opened students’ eyes to the world. Today, alumni are making sure she is not forgotten.

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos courtesy of the Civita Institute | September 2020

Astra Zarina was the type of teacher who would sweep into her architecture classroom at the UW Center in Rome and toss her wrap in one direction and her camera in another. Some of her students were dazzled. Others, wary. “In one of the letters I sent back to my mom and dad, I said this lady is so demanding and so egotistical, I don’t think I can ever be alone with her,” recalls Steven Holl, ’71, a now-famous New York-based architect. “She was a really forceful person.”

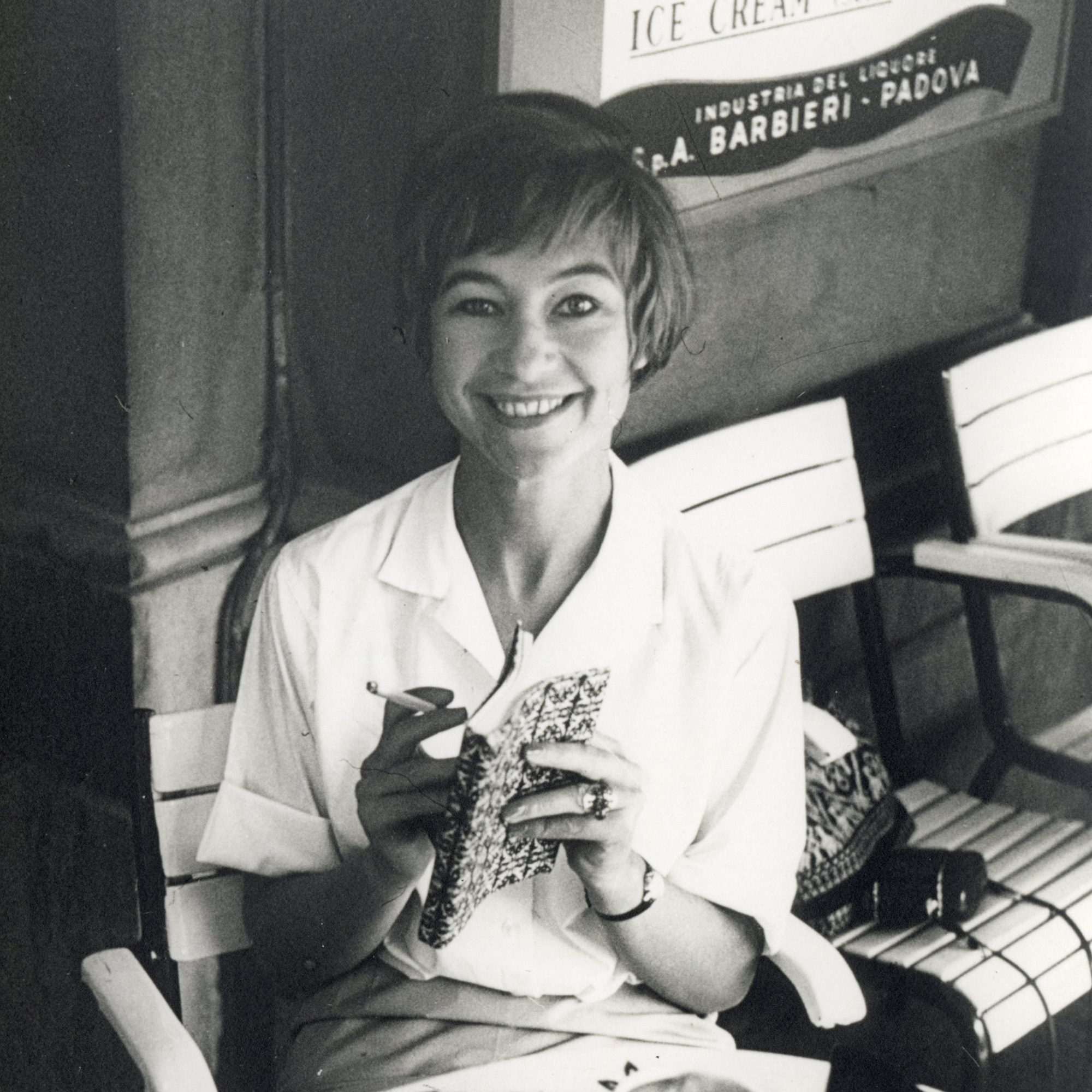

Zarina insisted that her students speak Italian. She dressed elegantly, had kohl-lined eyes and bobbed hair in the style of women in Rome in the 1960s, and she always seemed to be rearranging the objects around her. Fluent in English, French, German, Latvian and Italian, she was unlike anyone her students had ever met. Her design approach was human-centered and mindful of the natural environment. She emphasized preserving and reusing historic buildings. “She was ahead of her time,” says Holl, who was ultimately won over.

Nearly all of Zarina’s students in Rome fell in her thrall. “She was so enmeshed in architecture, art and culture, history and philosophy and poetry,” says Stephen Day, who was Zarina’s student and later her assistant in the early 1980s. “She was really a citizen of the world, perhaps more than anyone I had ever met.”

Zarina, a World War II refugee, became an asylum seeker, then a promising UW architecture student, then a talented architect and ultimately a teacher and visionary with the kind of magic that changes the people around her. Today, 12 years after her death, several new projects recognize this woman whose personal life and professional journey were dazzling and cinematic. Many women architects of her generation have been lost to history. But Zarina’s students—some widely recognized in their own right—are determined not to let that happen to her.

From the time she graduated, Zarina was on the move. Right out of college, she landed a job helping draft plans for midcentury modern homes at the firm of famed Seattle architect Paul Hayden Kirk, ’37.

Zarina was born into an upper middle-class family in Riga, Latvia, in 1929. She and her three siblings enjoyed comfortable childhoods in a beautiful, cultured city. But the Russian and German occupations of Latvia in the early 1940s upended their world. The family fled to Salzburg, Austria, to stay with relatives before ultimately taking refuge in the Austrian Alps near the Italian border. After several years at a refugee camp in Germany, the family sought political asylum in the U.S. and settled on a farm near Seattle—mistaking Washington state for the nation’s capital. They made the best of it, though, first trying farming and then with Zarina’s father working as a janitor at the UW.

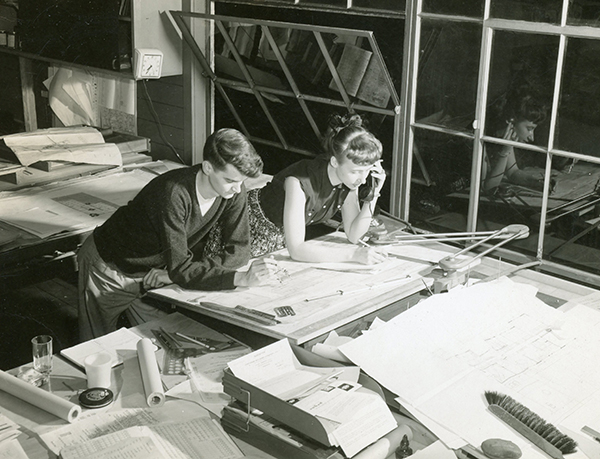

In 1951, Zarina enrolled in the UW School of Architecture. She flourished under the guidance of professors Wendell Lovett, ’47, and Lionel Pries. Victor Steinbrueck, ’40—who later led the preservations of Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market—was her mentor. She won a faculty award for excellence in design before graduating and starting work as a draftswoman at the prestigious Seattle firm of Paul Hayden Kirk & Associates.

Zarina was on her way. By the following year, she had enrolled at MIT for graduate school, where she graduated at the top of her class, the first woman to do so. She landed a job as a project designer with Minoru Yamasaki’s firm in Detroit. Yamasaki, ’34, who grew up in Seattle, was designing modernist buildings and developing an international reputation. His firm designed the World Trade Center in New York in the early 1960s and the Pacific Science Center in Seattle in 1962. A 2017 biography of him describes Zarina as “perhaps the most talented artist to ever work for Yamasaki.”

But Zarina wanted more. In 1960, she won both a Fulbright and the American Academy’s Rome Prize for Architecture. Those fellowships afforded Zarina two years of study in Italy. She arrived in Rome a modernist. But in the process of exploring and documenting Rome’s buildings and neighborhoods, her approach to architecture grew to include historical preservation and dedicated public spaces. After her studies ended in 1963, she returned to work, joining the design team of an innovative housing project on the outskirts of West Berlin. A couple of years later, she added teaching to her portfolio and traveled back to Seattle—where her family remained—to lecture at the UW College of Built Environments. Zarina loved her life in both cities but thought she could do more with her students if she could teach them in Rome. She lobbied the department leadership for the opportunity. Tom Bosworth, who became department chair in 1969, shared the vision of sending architecture students abroad and helped her design a study-abroad project in Rome.

“She taught us all these things that were central to being an architect. But then there was another dimension of learning—the cultural dimension.”

Steven Holl, ’71

Just a few years after graduating, Astra Zarina became the first woman to win the Rome Prize for Architecture. Her explorations of Rome and the countryside during the fellowship changed her approach of architecture and historical preservation.

The program launched in spring 1970, bringing five students to study the urban and environmental aspects of the city. Among them were Ed Weinstein, ’71—who now claims dozens of projects throughout the Northwest—and Holl, the internationally known, New York-based architect. Holl was just two years into his studies at the UW and debating whether to continue with architecture. “I wanted to drop out and be a painter,” he said during a recent Zoom interview from his home in Rhinebeck, New York. But his teachers urged him to stay the course. Professor Hermann Pundt even left him a note in his mail cubby, saying: “You must go to Rome.”

“I had never been out of the Pacific Northwest,” says Holl, who is today, as The New York Times describes him, “widely considered one of the most original talents of his era.”

Zarina opened the world to him, says Holl. “She taught us all these things that were central to being an architect. But then there was another dimension of learning—the cultural dimension.” Zarina’s studio was in the center of the city, her apartment and a roof garden on the floors above. She required her students to join her in the kitchen and help prepare special meals. One day, she handed Holl a spoon, a wooden bowl, eggs and olive oil and put him to work making mayonnaise. It took hours, he says. At the time, food wasn’t important to him. “I was the kind of guy who would eat a bologna sandwich and draw at the same time,” he says. “But she said, ‘If you’re going to be an architect, the first thing you need to do is learn how to cook.’” She taught students about meal planning, texture, presentation, utensils, eating and hosting.

Food and language became key parts of the program. The practice of cooking and entertaining—dubbed by Zarina as “didactic dinners”—started with scouring the markets for locally raised food and flowers and included setting the table and serving an array of appetizers and cocktails to the guests who were often a who’s who of Roman society. “And you were expected to make polite conversation,” says Kari Kimura, ’90, who today has an architecture practice with her husband Shaun Roth, ’90, in Hawaii. “Astra Zarina took a bunch of public-school kids, most of us were pretty rough, and gave us the experience to go into any situation and have a client dinner or a meeting. We called it finishing school.”

“Having gone to Rome, she became more and more intensely engaged in cultural and historical preservation.”

Stephen Day, ’84, ’97

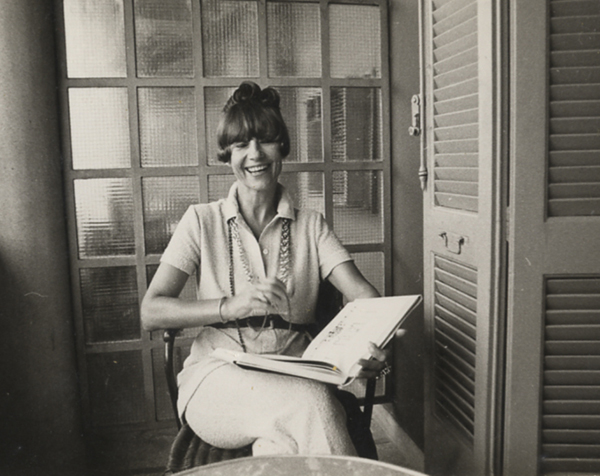

Food, conversation, history, design and teaching were all ingredients for la dolce vita for Professor Astra Zarina. Beyond offering up the city of Rome to her students, she taught them to look at life and their work from thoughtful and worldly points of view.

After the Rome program and graduation from the UW, Kimura and Roth followed Zarina’s path to MIT for graduate school. They embedded some of Zarina’s approach into their practice. They even have it on their business cards: “Architecture from the city to the spoon,” which means design at different scales from urban planning down to tableware, says Kimura.

In addition to feeding their stomachs, Zarina was feeding her students’ intellects. Holl’s small class accompanied their professor to the American Academy for lectures and to dinner with her famous friends at a favorite fish restaurant in the Trastevere neighborhood. She introduced them to luminaries like writer Gore Vidal, architectural historian Colin Rowe and artist Giorgio de Chirico. “She was a really interesting figure in Roman life,” says Holl.

When Stephen Day, ’84, ’97, was her teaching assistant in 1983, he escorted Zarina to a soiree at the American Academy. “I was just this kid from Lake City,” he recalls. Nonetheless, he was treated to a mind-bending evening. In addition to introducing him to architect and designer Michael Graves, Zarina shared her experience as a Rome Prize fellow. She described how it opened up her frame of reference for architecture and made her question her own assumptions as well as what she had been taught at MIT and the UW.

“She started as a very staunch kind of modernist, but having gone to Rome, she became more and more intensely engaged in cultural and historical preservation,” says Day, who does preservation work at his own Seattle firm. “The experience (of the Rome Prize fellowship) was pivotal for her and led to her wanting to establish the Rome program,” so that more students could explore the city in the ways she had.

A decade after starting the Rome program—which was supposed to happen only once but continued and grew because of overwhelmingly positive student response—Zarina found a site to house a permanent UW center in Rome: a derelict 15th-century building off the lively Campo de Fiori plaza that could be rehabilitated into classrooms, offices and apartments for faculty. After campaigning for and winning the University’s investment in the project, Zarina led the renovation, completing it with the help of students and her husband, architect Anthony Costa Heywood.

That she was able to negotiate for the space in the heart of Rome, persuade the University to do the project and oversee the renovation of the three stories that house the UW speaks to her many talents, says Nancy Josephson, a Rome program alumna from 1983. Josephson, ’85, watched the project unfold the following year when she returned to Italy to serve as Zarina’s teaching assistant. “She was very excited and proud that she could secure this home for the UW.” As the Rome Center expanded, Zarina welcomed students and colleagues from programs across the University to join in the exploration and study of the city. In addition to teaching, she ran the center—living in an apartment upstairs—until 1994.

Zarina’s biggest project was protecting Civita di Bagnoregio, a hilltop village in central Italy. She brought her students there to study the community and its buildings.

Another thread of Zarina’s life and work started during her own explorations of Italy in the 1960s. She discovered the Civita di Bagnoregio, an ancient settlement rising out of a hillside about 75 miles north of Rome. “The Dying City” had been built 2,600 years ago by the Etruscans on top of a mass of soft volcanic rock. Unstable yet stunning, the tufa stone and tile-roofed community of medieval buildings has long been a tourist favorite. Tour guide Rick Steves, ’78, calls it his favorite hill town in the world.

At Civita, Zarina found a new calling—repairing and protecting the village. On a whim, in 1961, she bought her first house there—a one-room building with a massive fireplace—and set about restoring it. Eventually, over decades, she laid plans for protecting the town as a whole. The Civita endeavor was the genesis of the UW Italian Hilltowns program, which Zarina started in 1976. The summer study-abroad program paired local families with UW students who would spend their months exploring and documenting Civita.

In the 1980s, Zarina and her hill towns students co-founded the nonprofit Northwest Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in Italy, today known as the Civita Institute. The Seattle-based organization offers fellowships, educational programs and exchanges between the U.S. and Italy. After Zarina retired from the UW in 1999, she and her husband focused their energies on Civita. In 2006, Zarina helped nominate the site for the World Monuments Watch to raise awareness of its vulnerability and need of preservation. The site is now a candidate for a UNESCO World Heritage designation. In 2007, the year before she died, Zarina and Heywood donated the properties they had restored to the Civita Institute. “It was definitely her intent to keep going with her kind of values and pedagogy through the institute,” says Josephson, who is now board president of the nonprofit. “This is her living legacy.”

Today the institute’s board includes a number of University of Washington alumni. And it has developed a permanent exhibit in Civita featuring Zarina, capturing her personal history as well as her restoration work.

Just by luck, another, unrelated, project to celebrate Zarina broke ground in Civita last spring. The “Astra Zarina Belvedere,” a bronze and stone sculpture designed by Holl includes four intersecting spheres—representing different areas of Zarina’s influence as architect, scholar and world citizen. Also, Holl has curated an exhibit about Zarina which opened last summer at his T-space gallery in Rhinebeck, New York. “Rome and the Teacher, Astra Zarina,” highlights another of Zarina’s projects, “I Tetti de Roma,” a 1976 book in Italian about the rooftops of Rome. The volume pairs her written descriptions of human spaces in Rome with spectacular black and white photography of Balthazar Korab. Zarina’s former students are endeavoring to republish the book in English.

Holl’s exhibit about Zarina was scheduled to arrive at the architecture school on the UW campus this fall, but it has been delayed because of the pandemic. Meanwhile, Holl currently has an exhibit of his own work, “Making Architecture” at the Bellevue Arts Museum. He designed the Bellevue museum in 2001, and the exhibit features his body of work. The final dates of the show are pending based on the museum’s Phase 3 reopening.