Our first astronaut Our first astronaut Our first astronaut

Richard Gordon expanded the UW's universe in 1969.

By Caitlin Klask | Photos by NASA | December 2022

When Richard Gordon graduated from the UW in 1951 with a chemistry degree, he had no clue he’d be one of only 24 people to travel to the moon. “Astronaut” wasn’t even in his vocabulary. When he was drafted, he decided to join the Navy and learn to fly. It turned out that he was good at it.

Gordon became a naval aviator in 1953, serving as a test pilot through 1960. He logged 4,500 hours in the skies, mostly in jet aircraft. He won the Bendix Trophy for setting a speed record flying from Los Angeles to New York City in just two hours and 47 minutes. He was ready for the next frontier.

“When you think about it, it’s a normal professional evolution,” said Gordon. “You learn to fly, and we were all carrier pilots when we went to test pilot school, and space, obviously, is … next.”

For Gordon, the timing couldn’t have been better: President Kennedy announced in May 1961 amid Cold War tension with the Soviet Union that the United States would be the first country to go to the moon. At that time, U.S. astronauts had never even orbited the Earth.

“The space race was real,” Gordon said. “We wanted to be better than the Communist country. And we were under a great deal of pressure because of the edict that President Kennedy sent down that we were going to go to the moon before the decade was over. So there was always that in the background.” He became the first UW alum to go into space.

Gordon’s role in the space race began on his 1966 Gemini 11 mission with Pete Conrad, who would later command their Apollo 12 mission to the moon. After Gordon’s tenuous spacewalk aboard Gemini 11, his second extravehicular activity involved photographing the Earth from just outside the ship’s hatch. He and Conrad, consummate professionals who had just set the record for the highest Earth orbit, were at ease.

“We were going over the Atlantic and he said, ‘Hey Dick, guess what, I fell asleep.’ And I said, ‘Guess what, I did too.’ It was nice and warm and cuddly.”

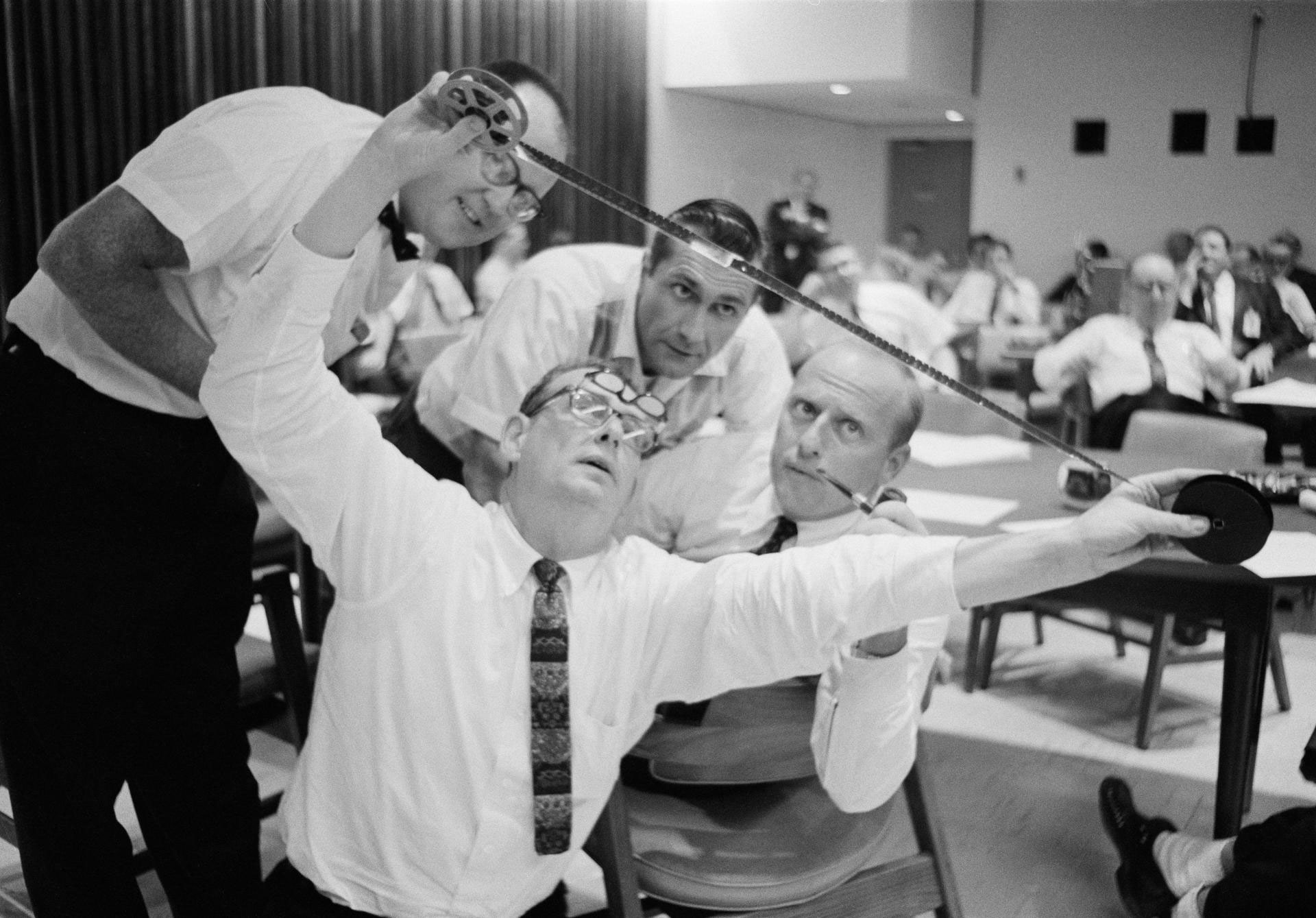

In September, 1966, Astronauts Pete Conrad Jr. (with pipe) and Richard F. Gordon Jr. (background) view negatives from their Gemini-11 mission. Photo credit: NASA.

In 1969, Gordon and crewmates Conrad and Alan Bean flew to the moon on Apollo 12. Bean, who had never been to space, wasn’t as qualified as Gordon to fly the lunar module, so he and Conrad landed on the surface of the moon while Gordon performed photography experiments in lunar orbit. When his crewmates returned after their lunar surface activities, Gordon was appalled at the amount of moon dirt they’d accrued on their spacesuits.

“They came back so damn filthy that I wouldn’t let them in the command module. I looked in there and said, ‘Holy smoke. You’re not getting in here and dirtying up my nice clean Command Module.’”

Though he was slated to finally walk on the moon on the Apollo 18 mission, budget cuts at NASA meant his space career was over. Gordon regretted nothing. He piloted a post-NASA career of wide-ranging work from aerospace engineering to professional football management and charity leadership.

“I had my turn and enjoyed every minute of it,” Gordon said in an interview before his induction into the Astronauts Hall of Fame. “End of chapter. Those days are gone forever.”

He died at age 88 in 2017. In Kingston, just a few miles from his high school alma mater, Richard Gordon Elementary School is dedicated to his memory.

“We’ve often been asked, ‘What did you discover when you went to the moon?’ We discovered the Earth,” said Gordon, reflecting on his NASA career. “Its beauty. Its apparent fragility. Its uniqueness in the solar system, maybe the universe. The sheer beauty of this planet is awesome.”

Click or tap to view photos with captions.

- The three crewmen of the Apollo 12 lunar landing mission are briefed aboard the NASA Motor Vessel Retriever in preparation for water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico. Two training personnel are in the background. Photo credit: NASA

- After a successful trip to the moon, the smiling Apollo 12 astronauts peer out of the window of the mobile quarantine facility aboard the recovery ship, USS Hornet. Gordon is pictured in the center. Photo credit: NASA

- On September 22, 1969, these three astronauts were named by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as the prime crew of the Apollo 12 lunar landing mission. Left to right are Charles Conrad Jr., Richard F. Gordon Jr., and Alan L. Bean. Photo credit: NASA

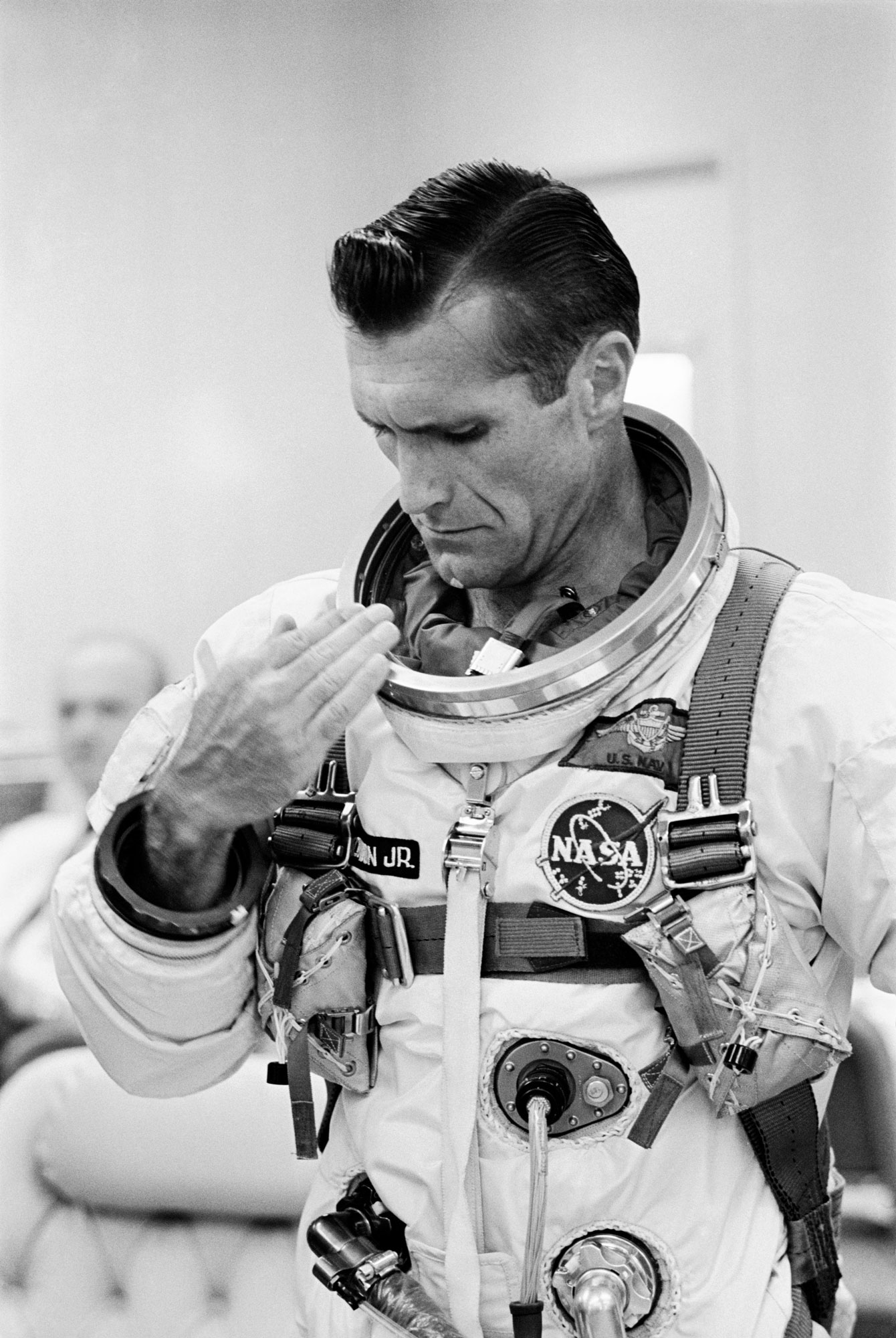

- Astronaut Richard F. Gordon Jr., pilot of the Gemini-11 spaceflight, suits up in the Launch Complex 16 suiting trailer during the Gemini-11 prelaunch countdown. Photo credit: NASA

- Gemini-11 prime and backup crews are pictured at the Gemini Mission Simulator at Cape Kennedy, Florida. Left to right are astronauts William A. Anders, backup crew pilot; Richard F. Gordon Jr., prime crew pilot; Charles Conrad Jr. (foot on desk), prime crew command pilot; and Neil A. Armstrong, backup crew command pilot. Photo credit: NASA

- Astronauts Pete Conrad, (right) prime crew command pilot, and Richard F. Gordon Jr., prime crew pilot, for the Gemini-Titan XI (GT-11) Earth-orbital mission. Photo credit: NASA

- A view of one-third of Earth, with Australia on the horizon, as photographed by the three-man crew of Apollo 12. The Command and Service Modules, mated to the Lunar Module (yet to be removed and transpositioned for landing) were en route to the moon for man’s second mission there. Photo credit: NASA

- In 2013, U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame member Richard Gordon was introduced at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. Photo credit: NASA