At the UW, CLUE isn’t a game, it’s a lively study hall At the UW, CLUE isn’t a game, it’s a lively study hall At the UW, CLUE isn’t a game, it’s a lively study hall

“Professor Chernicoff … in the hall … with the candlestick …” Nightly study sessions solve the puzzle of how to shrink the University.

By Niki Stojnic | Photo by Mary Levin | Sept. 2005 issue

Stan Chernicoff wants to shrink the University of Washington. Not literally, though his mad-scientist bristly hair and metal-framed glasses suggest he could think up a way to do it. Instead, the geology teacher set out two years ago to come up with a plan to make the sprawling UW campus feel more intimate.

“If you could capture the magic of a small liberal arts college and somehow infuse that in a place that has [the UW’s] level of excellence,” says Chernicoff, “then you’d have the perfect university.”

Chernicoff is attempting to tame the sprawl by bringing it under one roof with CLUE, the Center for Learning and Undergraduate Enrichment, an evening study center held in Mary Gates Hall that has no equivalent at any other university in the U.S.

It is part lively study hall, where students can drop in to do the night’s homework or solve a sticky problem; and part mini-college, with scheduled sessions for many of the 100- and 200-level lectures such as Introductory Biology, Prehistory of the Northwest Coast, Introduction to Political Theory, and Design Foundations. Chernicoff, an assistant dean in the Office of Undergraduate Education, estimates some 300 students turn up nightly. Predictably, attendance grows during midterm and finals weeks.

Around 6 p.m. Sunday through Thursday, Mary Gates Hall starts buzzing with students who gather with their books, laptops and notebooks at tables set up, Chernicoff says, to “cross-pollinate”—physics students next to language students next to math students.

Upstairs on the second floor, more specialized groups gather. In one room, several large, buff student-athletes are huddled. They greet Chernicoff warmly. They are there for the “nightly mandatory study table,” required by coaches so athletes have some blocked-out time for quiet and monitored study.

“It resonated with me that it was a wonderful thing for the student-athletes, and it has the effect of shrinking the University down to a more human size.”

Stan Chernicoff

These classroom sessions are what give CLUE first-of-its-kind billing. They are an opportunity for students, with only 12 to 14 classmates around, to ask questions and go deeper into their lessons, something there usually isn’t time for in a hall with hundreds of students and a teaching schedule to keep. Sometimes the class’s professor leads the session; others have a teaching assistant or tutor, with professors dropping in occasionally.

Katrina Deines, an associate dean in the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, teaches Appreciation of Architecture during the day and her CLUE sections at night. “I enjoy so much meeting the students in a smaller group. Large classes often have the drawback that they are electives, and students take them because they need the credit, not because they’re interested. It surprises them when they find they are interested.”

With the UW’s undergraduate population hovering around 26,000, students find that getting to know their peers—let alone their professors—is a challenge. “The student-athletes, they live in one world. And the students who study engineering—they’re in that complex over there,” explains Chernicoff as he points to the east. “The kids in the Greek system, they cross over 45th. The students of color spend their time at the instructional center [a daytime center]. Students who commute to campus, they’re all spread out by their living situation and by what it is they choose to study.”

Chernicoff, in a way, specializes in those who orbit outside the main axis of campus life—particularly student-athletes. He spent six years as an assistant athletic director overseeing academic support for all UW student-athletes. He found that the demanding travel and training schedules of athletes often make it impossible to go to nine-to-five study centers or a professor’s office hours. Instead, the UW set up a study program just for them. “Four to five students from different teams would sit down if they were all taking Psych 101 together [and] they would talk about the course,” he says. Tutors meandered among them ready to help.

“It resonated with me that it was a wonderful thing for the student-athletes, and it has the effect of shrinking the University down to a more human size,” says the effusive Chernicoff, who was influenced by his own mega-university experience. He was one of more than 50,000 students at the City University of New York at Brooklyn, and completed his graduate studies at the University of Minnesota, “a big state university very much like the UW.”

The well-loved professor has earned numerous accolades: Most recently, he won the 2005 James D. Clowes Award for the Advancement of Learning Communities. In 2000, he won a UW Distinguished Teaching Award. His Introduction to Geological Sciences class (popularly known as “Rocks for Jocks”) has attracted droves of students over the years. In it, Chernicoff is famous for “shrinking the University” by memorizing all of his students’ names.

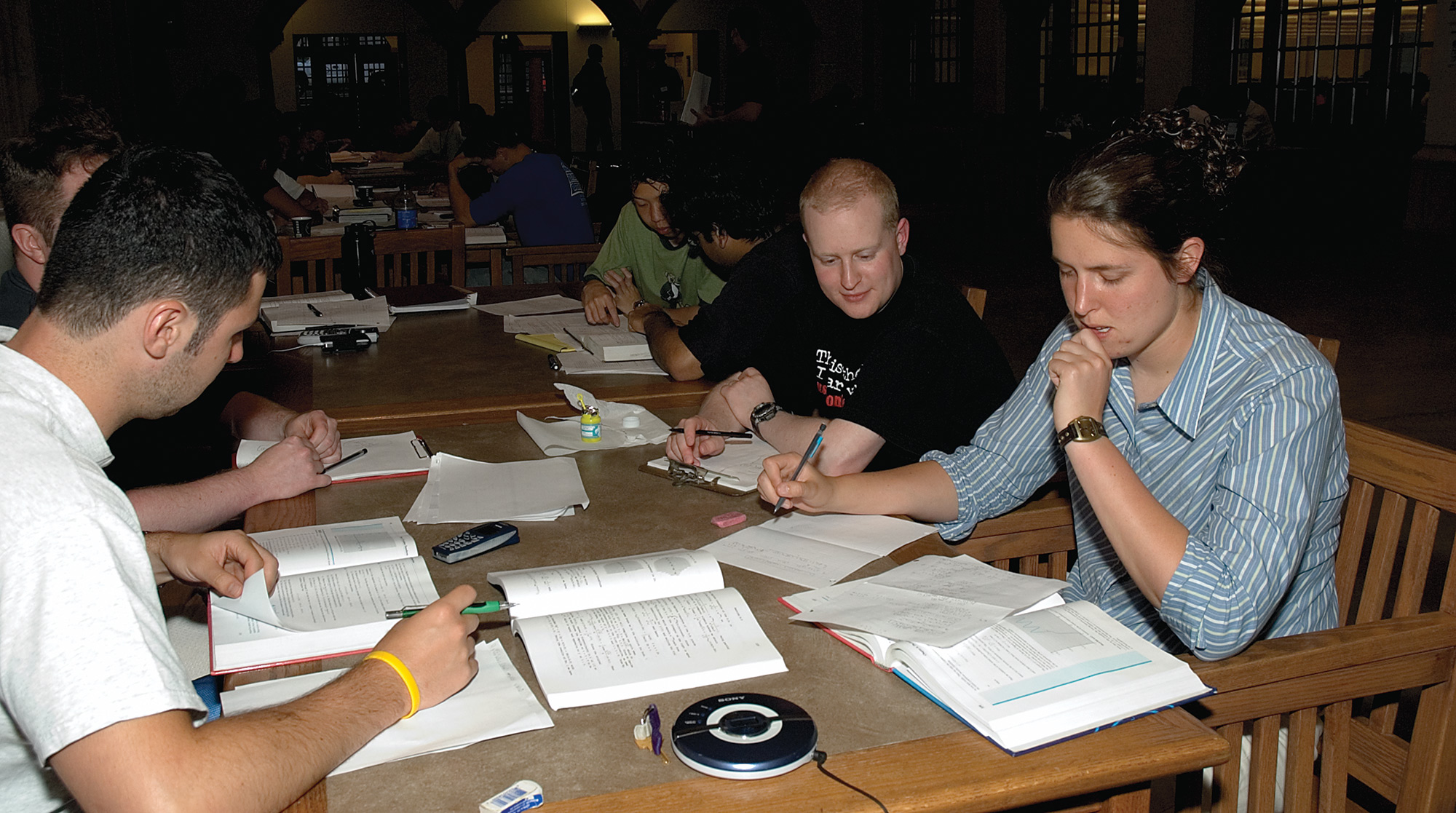

CLUE founder Stan Chernicoff (center) consults with students.

But it wasn’t until he watched the athletes’ study groups that Chernicoff got the idea for CLUE. Why not let everyone on campus benefit from this study system? In early 2003, he ran the concept by his students and those who run the other study centers on campus. He assured everyone that CLUE would open when the other centers close to avoid overlap. The response was enthusiastic.

Meanwhile, Dean of Undergraduate Education George Bridges (who has since left for Whitman College) helped secure funding, which comes out of the $250 enrollment and matriculation fee that entering students pay.

But for all of the encouragement Chernicoff received for his bright idea, he knew the real test would come on opening day. “We didn’t know whether 100 students would come in, or a thousand,” he says.

In fact, that first night in October 2003, CLUE welcomed all of six students, who came for the drop-in study tables. But Chernicoff refused to be discouraged.

Word of mouth spread quickly. At the end of the school year, “45,000 visits took place averaging 300 to 500 students a night. Now we are well beyond that,” he reports. As for the original six CLUE students, one continued to come for the rest of the term.

It’s going to take some time, Chernicoff says, to conduct research on CLUE’s effect on student performance, such as boosting grade point averages. But students have provided plenty of anecdotal evidence that CLUE is having an impact.

Jobs, extracurricular activities and noisy roommates can eat away at precious study time. “You absorb more here,” says mathematics junior Paul Mulvaney, who comes to CLUE regularly. “The people here explain [the material] better, and it’s a very good place to study.”

“I set things up so that the computer science students are sitting next to the French students – with the hope that they will enjoy meeting people who are a little bit outside their group.”

Stan Chernicoff

Education graduate student Peter Cheng, one of the CLUE tutors for math and physics, says that he would have attended a program like this if there had been one at his undergraduate university. “It’s accessible to students when they need to study.”

Professors, such as Deines, appreciate their CLUE time as well—particularly when there are illuminating moments that veer away from reviewing the day’s class notes. “I can recall a great conversation about the motif of the mandala, which is used in Hindu architecture and Buddhist culture and architecture,” she says. “We all learned more about the mandala that night, thus more about South Asian cultures and the relation of this to architecture. I appreciate times in which it’s clear to me that culture and architecture are clearly linked in the students’ minds.”

Teaching Assistant Leah Sprain estimates she had about 20 percent of her Introduction to Public Speaking class coming to CLUE. Rather than review, students were able to use the time to practice speeches, solidify outlines and deal with speech anxiety.

Strolling among tables early in a CLUE evening, Chernicoff lights everyone up with his energy, his razor-sharp mind apparently never forgetting a name. “I set things up so that the computer science students are sitting next to the French students – with the hope that they will enjoy meeting people who are a little bit outside their group,” he explains.

The social component is as important as the academic, he says, because a student who has fun learns more. “The University wants to be an inviting place that really has all students from all backgrounds achieve at the highest level. But it can’t unless it really feels comfortable and they feel as if they belong to something,” he says. And they do, according to Matthew Caine, a mathematics senior. “It’s friendly. People come to hang out.”

Academically, students benefit from making CLUE a habit, according to Chernicoff.

“It enables us professors to coerce the students to do what’s called ‘distributed learning.’ You don’t just cram the night before, because you never remember it after that. If you study a little bit every day before an exam you distribute your learning of that subject and it goes into a deeper memory.”

Alas, many undergrads wear their cramming skills as badges of honor. So professors find it necessary to help encourage the CLUE habit with incentives such as extra credit. Chernicoff feels it is justified: “They’re spending an extra hour and a half to three hours per week thinking and studying in this subject area.”

Rather than give credit, Biology Lecturer Linda Martin-Morris has tried other things: Baking brownies (“I’m renowned for my brownies,” she jokes) as well as having students help write exam questions. But she finds turnout can be lower for CLUE sessions without the carrot of extra credit.

Economics Professor Haideh Salehi-Esfahani offers credit to those who attend over half the sessions for her Principles of Macroeconomics class. She says that the better the tutor, the better the attendance. She feels that CLUE should not function as a replacement for a student’s own study time. While CLUE worked well as a review, she would have preferred the sessions stay closer to what she sees as the original intent of CLUE: “to take the classroom a little bit further.”

Deines’s classes also usually serve as review sessions, but she sees that as an asset. She uses the time to clarify confusing points for students. The intimate atmosphere of her CLUE get-togethers makes her large lectures more interactive. “Because I get to know the CLUE students a little better, there is a more open atmosphere in the big lecture—people will raise their hands or come speak with me after class,” she says.

With such a diverse program, CLUE’s success varies by class. Public speaking TA Sprain found that her main challenge was dealing with the ebb and flow of attendance. “Some CLUE sessions no one would come and then the next week we would have 20 students. This pushed us to be creative in managing time,” she says.

The program faces some potential challenges as it enters its third year, such as funding. Thanks to its popularity, the program may eventually need more space as well. “We may at some point outgrow the building,” says Chernicoff, “which would be unfortunate because then we’d have to use more than one space and the whole idea behind CLUE was to centralize.”

But ultimately, being too popular is cause for celebration. CLUE is gaining recognition and inquiries along the West Coast, and Oregon State University in Corvallis is the first to be looking into starting a similar program.

With the UW’s new school year set to kick off later this month, Chernicoff will face the challenge of shrinking the University for 4,900 new freshmen.

“Students make the choice to come to a university like this because of its research opportunity, excellence of faculty, location and facilities. But the tradeoff is you don’t connect as well with the faculty, your classmates, with the graduate students that run the sections—because there are just so many students.” says Chernicoff. CLUE is a way around that. “As it grows, you can’t put the genie back in the bottle. The students have demonstrated they love this.”