Hero

in crisis

Hero

in crisis

Hero

in crisis

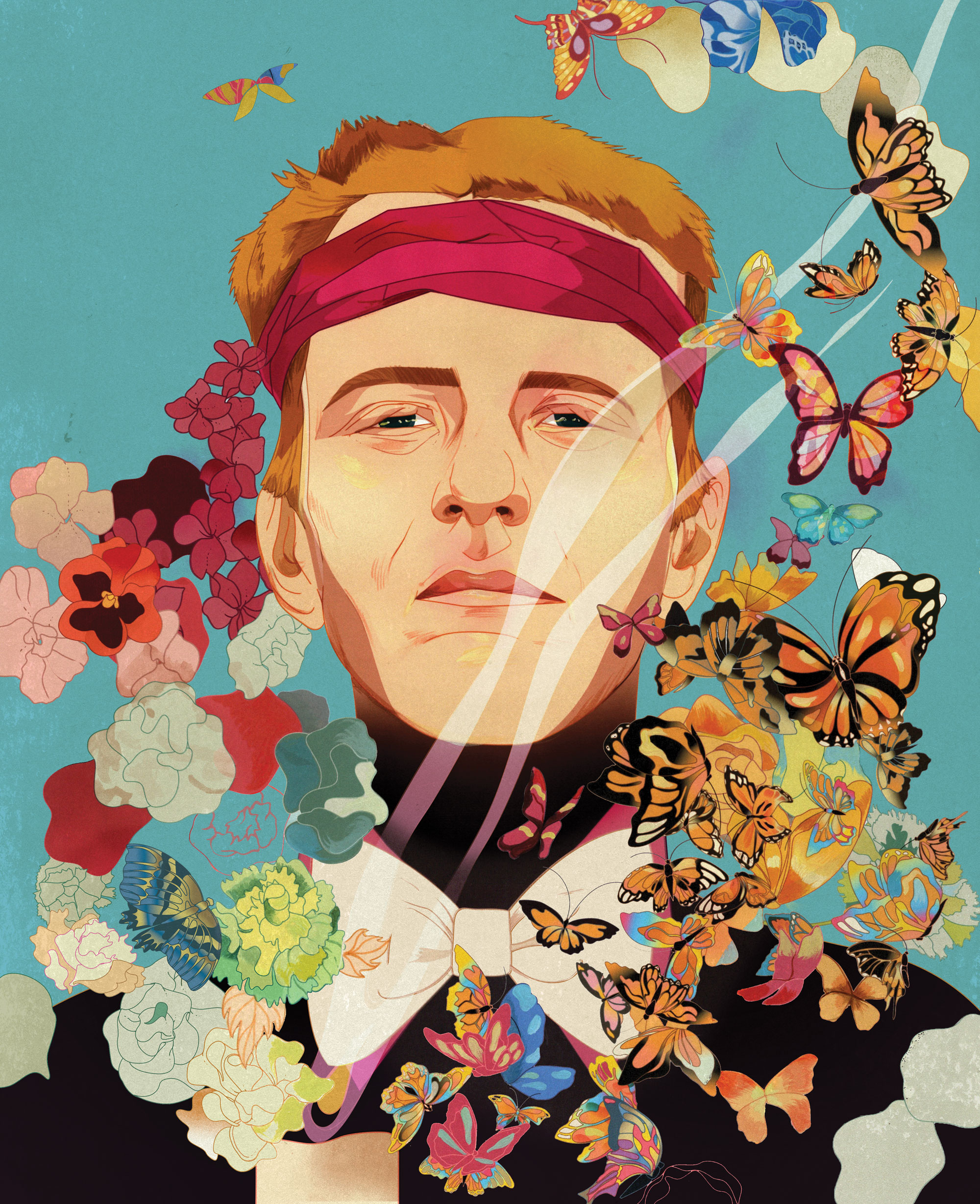

Celebrating Bobbi Campbell, one of the first AIDS activists.

By Liam Blakey | Art by Marcos Chin | June 2024 issue

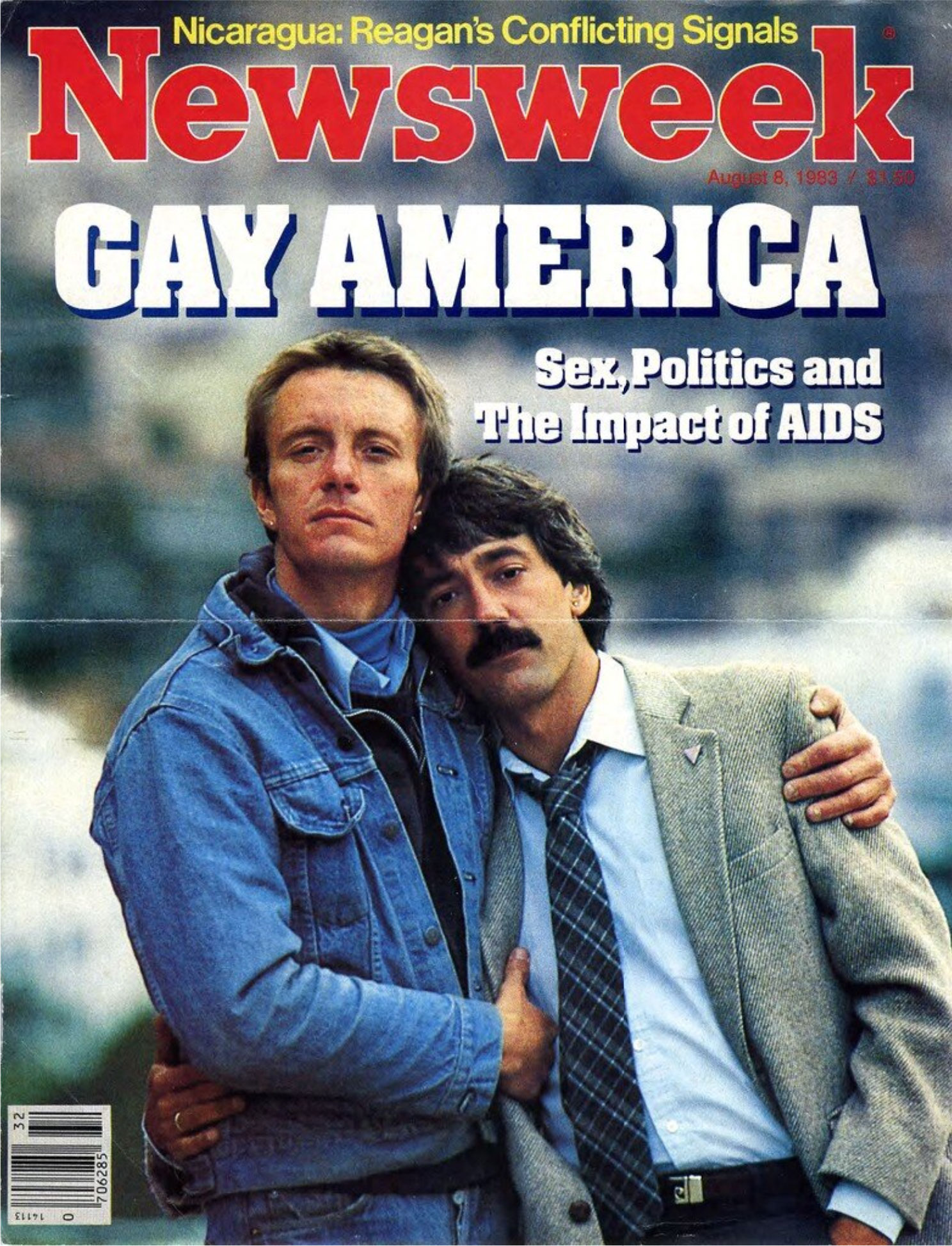

In the early hours of Aug. 8, 1983, Newsweek magazine was delivered as usual to newsstands, grocery stores and mailboxes. But the story that graced the cover was different from what readers were used to seeing. Under the headline “Gay America,” Bobbi Campbell, ’74, stood with his arm around his partner, Bobby Hilliard, giving the nation one of its first views of a person with AIDS.

That cover was a critical point in a decade of activism that started for Campbell in the neighborhoods of Seattle and the hallways of the University of Washington. A few years after graduating and leaving the Pacific Northwest, Campbell took what he learned as a nurse and gay-rights activist and brought AIDS into public view as the first person in the nation to go public with his diagnosis.

The cover of Newsweek on August 8, 1983 featured Bobbi Campbell (right) and his partner Bobby Hilliard.

So often, Campbell’s story is told in a few brief sentences. He was a UW School of Nursing alum who moved to San Francisco in the mid-1970s. He worked as a nurse in the Castro District before becoming the 16th man in the city to be diagnosed with a rare skin cancer called Kaposi sarcoma. He gave voice to the experience of being a person with AIDS and awakened the nation to the reality of the disease. But there’s more to his story.

“My first memories of Bobbi were of someone who was handsome, quick-witted, funny. A dear man who was liked by a lot of people,” says Robert Perry, a Gay Liberation Front member who knew Campbell in Seattle in the ’70s. “He really wanted to be worldly and feel everything that you could in life. Him being on that Newsweek cover and being interviewed really put a face to the disease and humanized AIDS to the masses of people.”

Born in 1952 and raised in Tacoma, Campbell attended Lakes High School. He moved to Seattle in the early 1970s to study at the UW and volunteered at the Seattle Counseling Service, the first gay-run resource in the country to provide mental-health services to the queer community. It was founded by UW pediatrician Dr. Robert Deisher.

And at a time when Seattle’s gay community was coming out of the shadows, Campbell joined the movement. In 1969, a six-day conflict between the gay community and the police at the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in New York City, had signaled a national change in LGBTQ+ activism. Now known as the Stonewall Uprising, it was the dawn of the gay community mobilizing against discrimination, the criminalization of homosexuality and police brutality.

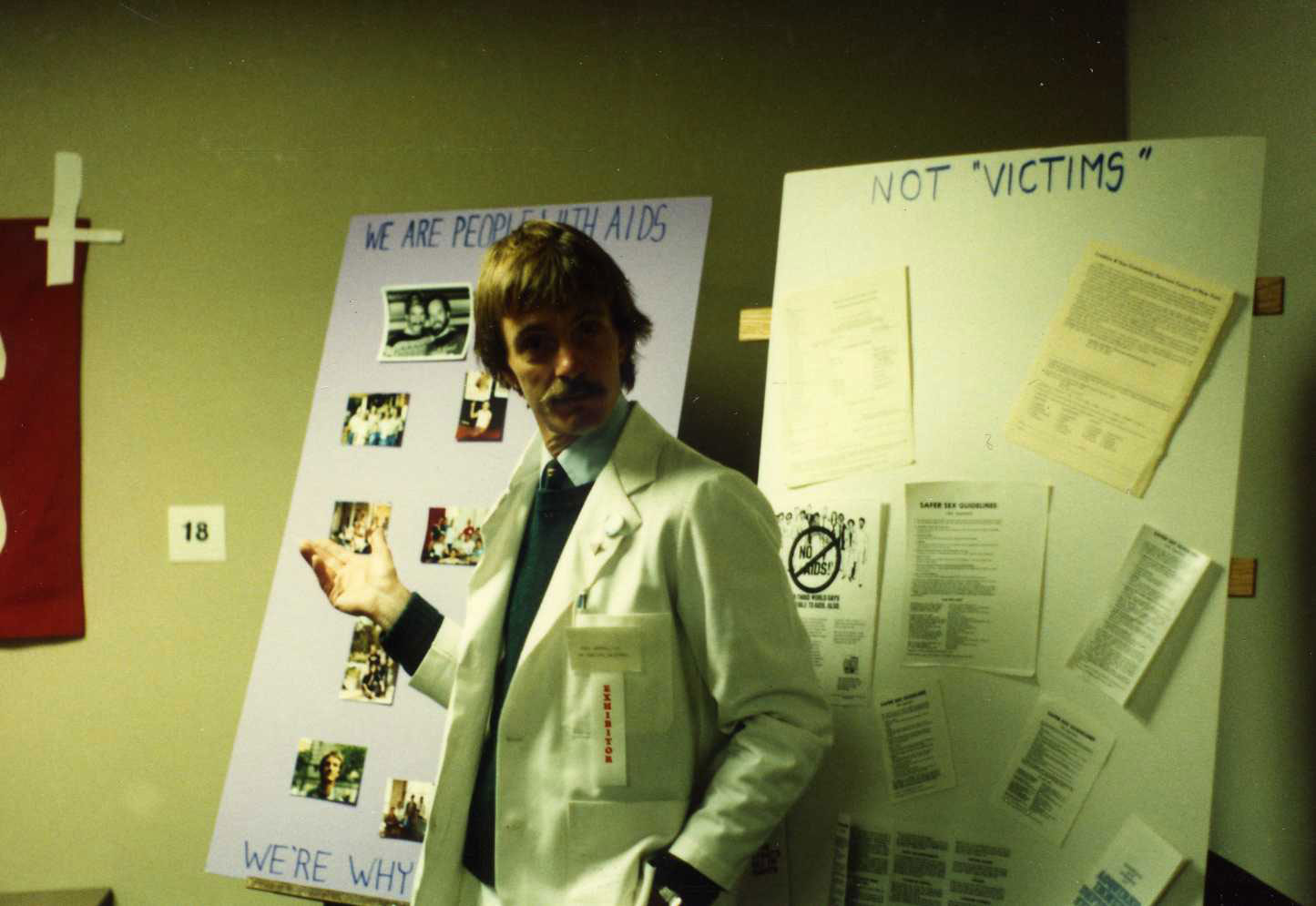

Bobbi Campbell exhibits information at the Clinical Nursing Conference on AIDS at NIH, October 7, 1983. Photo sourced from Bobbi Campbell’s Diary, via UC San Francisco Library, Special Collections.

“After Stonewall, there’s just this flourishing of gay groups all over the country,” says UW history professor Laurie Marhoefer, whose expertise includes queer and trans politics. “People got together and organized—there’s a lot more of an appetite to come out in this moment. Pride parades start and the Pride parade itself is so radical because to walk down the street and let everyone see that you’re in this parade, you’re letting everyone see that you’re gay. … You were risking lots to do that.”

The activists in Seattle were not only interested in building community and awareness, but in passing laws and undoing legislation that attacked their very existence. Perry describes a protest at a roller rink in Lynnwood when, during a couples-only skate, a group of gay people went into the rink together. “We were arrested, wheeled off and kept in jail until 5 a.m.,” he says. “When the case went to trial, everyone in the community came out, and this would have been my first contact with Bobbi. I decided to dress up in my finest for court and was told that I made a mockery of justice.”

Soon, San Francisco and its larger, more open queer population drew Campbell away from Seattle. He moved in 1975 and went to work at Ralph K. Davies Medical Center in the Castro District.

A few years later, when he was not yet 30 and studying to become a nurse practitioner, Campbell was subject to a series of illnesses. It started with the shingles and eventually lead to the diagnosis of a rare cancer known as Kaposi sarcoma. It was 1981 and an unknown disease was causing pneumonia and rare cancer in young men in Northern California and New York. This was the year before the human immunodeficiency virus was isolated and the term “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” (AIDS) was introduced.

Drawing on the skills he learned as an activist and as a public health nurse, Campbell immersed himself in understanding his ailment and demystifying the AIDS story for others. AIDS was being written off as a “gay virus,” but Campbell made it his mission to speak, write and be the public face of a disease that was widely obscured by fear, shame and discrimination.

He wrote a column for the San Francisco Sentinel about his experiences having AIDS that was syndicated to newspapers serving gay communities around the country. In 1981, he hung a sign in a Castro District pharmacy describing the symptoms of the then-mysterious disease and included pictures of his own Kaposi sarcoma lesions, urging others who might have them to seek medical attention. The following year, he cowrote “Play Fair!,” perhaps the first-ever brochure urging safer sex practices for gay men—and it did so with humor and sex-positive language. It was published by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a group of queer and trans “nuns” who playfully devote themselves to community service, outreach and promoting human rights. Campbell was a member.

But it was his appearance on the cover of Newsweek that brought the burgeoning crisis into view for the American public. In the 3½ years from his diagnosis to his death, Campbell made every effort to educate the gay community and the greater public about the disease. Refusing to be called a victim, he and Dan Turner, another person with AIDS, founded what would become the People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement to demand to be treated with dignity, take an active role in their own care and receive fair treatment from employers, landlords and people in general. Campbell spoke at health conferences and community meetings around the country.

In 1983, he visited Seattle to appear at the Broadway Performance Hall. “This is a disease that affects Americans. It is in America’s best interest to solve it,” he is quoted in an Associated Press story about the event. “I’m simply asking people to put aside their prejudices toward homosexuals and see that we are humans fighting for our lives.” At the time, fewer than 2,000 Americans were reporting that they had AIDS. Today, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 1.5 million people in the U.S. have HIV.

On Aug. 15, 1984, Campbell died in San Francisco General Hospital. He was 32. Two days later, Castro Street was closed and nearly 1,000 people, including his parents and his partner, gathered to remember him. The following year, the San Francisco Pride Parade was dedicated in his memory.

In a story in Boston’s Gay Community News, Patrick Haggerty, an activist from Seattle, described his dear friend Campbell as “a geographer and a geologist and a hiker and a mountain climber; he spoke three languages; he was a poet, and a keeper of journals for 15 years.

“Whatever Bobbi Campbell did, he did it all the way,” Haggerty said. “That was his response to AIDS, telling us, ‘Get off your butts and do something.’”