The

Nisei

story

The Nisei story

The Nisei story

‘Boys in the Boat’ author Daniel James Brown tells a different story of heroism—that of World War II-era Japanese Americans.

By Hannelore Sudermann | September 2021

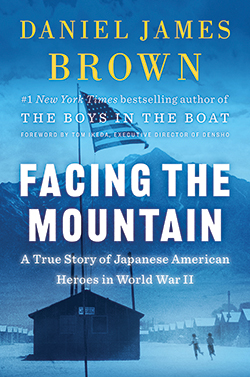

The writer who returned the 1936 UW crew team to the national spotlight with his book “Boys in the Boat,” has again trained his focus, in part, on the UW. In “Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II,” Daniel James Brown centers on four Japanese Americans, two of whom hailed from Washington and had UW ties.

The idea sparked six years ago when Brown and Tom Ikeda, ’79, were sitting on a Seattle stage, both about to be honored by the mayor. Ikeda is the founding executive director of Densho, a nonprofit that preserves and shares the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. They talked about the current racial profiling, detention and travel bans and how similar it was to the treatment of Japanese Americans during WWII. Ikeda followed up by sending Brown transcripts and links to Densho’s archives. “Dan came back with really interesting questions,” he says. “We started diving into it more and more.”

The Densho recordings included interviews with Gordon Hirabayashi, ’46, ’49, ’52, ’08, who, as a UW student, refused curfew and evacuation orders because they were unconstitutional. As Brown describes it in the book, Hirabayashi was rushing from Suzzallo Library one night, trying to get to his U District apartment before the 8 p.m. curfew, when he decided to resist.

Using interviews from Densho and Hirabayashi’s own papers in the UW archives, Brown builds his scene: “Then, suddenly, walking briskly across Parrington Lawn, he’d stopped dead in his tracks.” And he returned to the library.

“It’s about racism, it’s about anti-Asian racism, it’s about the immigrant experience.”

Daniel James Brown

“Gordon was a really interesting guy with very deep connections to the UW,” says Brown. Later, Hirabayashi was told to board a bus to ultimately be taken to an internment camp. “But he didn’t get on the bus,” says Brown. Instead, he wrote a detailed statement that the evacuation was unconstitutional and then turned himself in to the FBI. “It was classic Gordon,” says Brown. “Literally nobody else had said ‘No’.” His brave refusal landed him in federal prison and turned into a legal battle that lasted the course of the war.

Fred Shiosaki’s story was different. While Hirabayashi was fighting for constitutional rights, Spokane-born Shiosaki was fighting Nazis as a member of the 442nd Combat Team. When he tried to enlist the day he turned 18, he was rejected as an “enemy alien.” But later, he was able to join the 442nd, an all-Japanese American unit now famed for its bravery and sacrifice. There are other books about the storied unit, but most of them focus more on military details and less on the individuals, says Brown. “I was able to make it more personal by introducing some of the characters before they get into some of the horrific conditions,” he says. Brown heard much of Shiosaki’s tale firsthand, traveling to Spokane to interview him. (Shiosaki attended the UW after the war before returning to Spokane. He died in April).

While the book details the battles of the 442nd as the unit fought Nazis in Italy and France and saved the lives hundreds of American soldiers, it tells a deeper story, too. “It’s more about the human dramas that unfold,” says Brown. “It’s about racism, it’s about anti-Asian racism, it’s about the immigrant experience.”

While the book details the battles of the 442nd as the unit fought Nazis in Italy and France and saved the lives hundreds of American soldiers, it tells a deeper story, too. “It’s more about the human dramas that unfold,” says Brown. “It’s about racism, it’s about anti-Asian racism, it’s about the immigrant experience.”

Conscious as an outsider to the Japanese American community, Brown worked with Ikeda to connect with community leaders and the families of his subjects. “I was very seriously trying to get this right,” Brown says. “I’m acting as a historian here. The story I’m telling is based almost 100% on firsthand, first-person accounts. I’m using whatever skills I have as a storyteller.”

The Japanese American community has welcomed the book, recognizing the value of a fresh telling of a difficult history, says Ikeda. “Dan has a special kind of talent, telling these human stories,” he adds. It’s not simply a recounting of the experience of Nisei soldiers and activists, “it is an American story.”