‘Boys’ on the big screen ‘Boys’ on the big screen ‘Boys’ on the big screen

‘Boys in the Boat’ makes UW a character in a major motion picture.

By Hannelore Sudermann | December 2023

The Husky Clipper, a racing shell hand-built from Western red cedar, carried the UW’s Varsity 8 men’s rowing team to its dramatic win at the 1936 Summer Olympics. The boat, built in a workshop in the rafters of the ASUW Shell House, carried a story of hardship, hard work and ambition, as precious as the gold medals the eight oarsmen and their coxswain brought home from Berlin.

“A gleaming, beautiful boat” was how George Pocock, the ex-pat Englishman who designed and built the sleek 60-foot shell, described it. According to his notes, when he christened it with the team in the early spring of 1936, he wished it “success on all the waters it speeds over. Especially in Berlin.”

But that special piece of UW history, that essential heirloom of the team that brought the University of Washington to the world’s attention, once briefly floated away from campus.

In the mid-1960s, a time when the story of the Olympic champions had become embedded in the training and lore of the newest UW rowers, recognition across campus had waned. A few who recalled the Huskies’ global triumph imagined reviving the story by hanging the Husky Clipper from the ceiling in the newly renovated Husky Den. It would, according to their letters, “improve the college tone and atmosphere of the space.” Steve Nord, the Husky Union Building manager, went hunting for the boat.

But it was gone, says Paul Zuchowski, former associate director of the HUB and its historian emeritus. For decades, the boat had been tucked away in the racks of the Conibear Shellhouse, brought out for occasional events and whenever the crew of 1936 came to campus for a reunion. But in 1963, it had been given away, and to whom wasn’t clear, Zuchowski says.

That’s not a surprise, says head coach Michael Callahan, ’96, who as a student rowed for the UW and was captain of the 1996 team. The UW was in the habit of sharing older shells with rowing programs around the state, he says. “It was in the spirit of encouraging future athletes and strengthening the rowing community.”

A careful search revealed that the historic vessel had been delivered to Pacific Lutheran University’s emerging program 45 miles to the south. The Lutes who learned to row in the old UW boat were well aware of its history and reverently kept its original name and paint intact.

But with Nord’s request for its return and support from the UW athletics department, the rowing program arranged to trade another UW boat (so as not to leave PLU without a shell) and sent a truck down to Tacoma to bring it home. After several months of refurbishing, the racing shell was displayed in the HUB from 1967 until 1975, when it was sent back to the racks to make room for another HUB building project.

* * *

The Husky Clipper crosses the finish line first in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin.

Over the years, the University has grown to cherish its rowing history. From the time the earliest teams dominated the West Coast to national champions and Olympians throughout the decades, the sport has often held a prominent place in campus culture. A few books, reunions and newspaper stories rekindled public interest in the story of Washington’s first Olympic team. But as the members of the 1936 crew grew older, their limelight dimmed.

By 2007, only two members of the ’36 team remained. And Joe Rantz, the team’s No. 7 seat, was dying. His daughter, Judy Rantz Willman, had heard her father’s history in bits and pieces growing up. But it wasn’t until his last few years, when Joe moved into her home, that they started talking more deeply about his story. The move unearthed a trove of photos, news clippings and memorabilia, prompting him to share more details about his tumultuous childhood, when his folks abandoned him, and about his time on the team, where he found a new family. Willman took notes whenever a story or detail spilled from her dad. It was an incredible, against-the-odds tale, but “I could feel the threads of the story slipping away,” says Willman. “I didn’t want dad’s memories forgotten. I didn’t want what those boys had accomplished forgotten.”

At one point, she cobbled together a nine-page biography “with Dad’s childhood, the story of the race itself, the Great Depression and the building of the Grand Coulee Dam,” she says. She read it and reread it, convinced that her father’s story was exceptional. “But I needed somebody to take a look at it who would understand if it had merit or not,” she says.

She reached out to her neighbor, Daniel James Brown, who had recently published a historical nonfiction thriller. Reading his popular book, she appreciated Brown’s penchant for blending narrative with deep research. His writing transported her to another place and time, she says.

Rower Joe Rantz’s Olympic jersey.

Brown visited the Willman home and sat with Joe Rantz, evermore engrossed in his tale. The author took notes and asked questions as long as he dared.

After Rantz died on Sept. 10, 2007, at the age of 93, Brown turned to Willman for help filling out her father’s story, grateful for her record-keeping and observations. He also dug into the UW Libraries archives and old newspapers and visited the families of the other team members: Roger Morris, who died in 2009, Chuck Day, Johnny White, Jim McMillin, Gordy Adam, George Hunt, Don Hume and coxswain Bobby Moch.

To learn more about rowing, coaching and UW tradition, he turned to coach Michael Callahan, former coach Bob Ernst, former assistant coach Luke McGee and Eric Cohen, ’83, who was a UW coxswain and has served as the team historian since 2003.

Like Rantz, Cohen could describe the experience of being on crew, the training and the number of rowers who would turn out and would then, over the first few arduous months, drop out. “It’s grueling work in grueling conditions,” Cohen says. “It does require a certain personality.”

As a campus right on the water, the UW has a long history of rowing. It also has a history of training world-class athletes who had never before stepped into a shell. “There are so many stories to tell,” Cohen says. “As steward, coxswain and historian, I always felt uncomfortable talking about just one team.” In addition to the historic team of 1936, he points to the Husky 4+ rowers who won Olympic gold in 1948 and the many other men and women rowers who dominated in the Pac-12 and national championships over the decades. “They found the same swing,” he says, “the same love for each other.”

But they didn’t triumph in front of the Nazis on the eve of World War II, they didn’t all face the hardships of the Great Depression, and they didn’t have Daniel James Brown, who traced the path of the team of 1936 to Germany and stood on the shore where the Olympics were held to smell the air and feel the wind.

“They really wanted to understand each member of the boat, each character. People forget they weren’t just athletes. They were students.”

Alanya Cannon, UW director of brand management

After years of research and writing, Brown navigated the story of Rantz and the team into an international best-seller. The day Brown’s agent sold the book rights, the movie rights sold too. “The Boys in the Boat” was published in summer 2013. Within a few months, it had climbed into The New York Times best-seller list, where it took the No. 1 nonfiction spot. It sold more than 3 million copies.

“Right away when the book came out, there was buzz,” says Alanya Cannon, director of brand management at the UW and the point person for anyone who wants to use the UW campus for filming or photography. Cannon’s job evolved to include managing requests around the story.

While the University and the community around it have long been celebrating the history of the 1936 team, new fans, sometimes strangers to the Northwest, started appearing along the UW’s Lake Washington shore to wander around the ASUW Shell House and look across the waters where eight oarsmen and a coxswain found their near-perfect unison.

In 2016, a PBS American Experience episode inspired by Brown’s book carried the story of “The Boys of ’36” to an even broader national audience. “The documentary brought out a lot of material that was new to us too,” says Willman. “We had so many years of seeing these classic photographs of Dad and the guys, and now we’re watching them on film, moving and smiling and climbing out of the boat and poking each other. It was just amazing to see.” While it seemed that plans for turning the story into a movie had stalled, “we thought it was OK even if nothing else ever happens,” Willman says. “It was so good in terms of bringing the story to life.”

Then, out of the blue in 2018, news spread that MGM Studios was moving ahead with a “Boys in the Boat” movie in partnership with Smoke House Pictures, with actor and director George Clooney involved. At that point, “it became real,” Cannon says. “Then everybody got super excited.”

People love the story of an underdog, and the UW team shows, “that you can pull yourself up from nothing and succeed,” says Clooney in an MGM featurette. “The actual story of what they went through was really spectacular.”

* * *

What do you do when your university becomes a character in a major motion picture? Connecting with the MGM team, the UW’s Marketing and Communications team worked with the UW Libraries archives and the rowing program to assemble a handbook of all things UW, adding photos, footage and biographies of the rowers and details of what their days on campus would have been like—attending classes in the Quad and walking in view of the Gothic spires of Suzzallo Library. They paired photos of the 1930s coaches shouting at the rowers through bullhorns with detail shots of the sliding seats and wooden footplates in the Husky Clipper. They showed the ASUW Shell House from all angles, including Pocock’s original boat-building studio in the back. They featured the oars with solid white blades that the Huskies always used, and Moch’s megaphone, and Rantz’s Olympic jersey. They even added a pronunciation guide for words like “SAY-lish” and “spo-CAN.”

George Pocock designed and built the Huskies’ racing shells in his workshop at the back of the ASUW Shell House.

With each phase of developing the movie, the filmmakers would reach out to the UW for more details. First came building the sets—and that included a producers’ visit to campus to flesh out their understanding of the landscape and explore the shell house where the rowers would store their oars and boats. A 3D scan of the structure helped the filmmakers create an accurate to-the-inch version on the set in England. The set team wanted pictures of nuts, bolts, woodgrain and doorknobs, says Cannon. They wanted to know the ASUW Shell House’s original paint colors. “While many requests were easy to fulfill, that one was difficult,” says Cannon. “There were no color photos.”

Next came outreach to the families for help with elements like shoes, uniforms, and buttons and zippers on the letterman jackets. The movie team sought snapshots of the rowers to get a sense of each man’s personal style.

Someone in the chemistry department uncovered Joe Rantz’s transcripts in the basement of Benson Hall. With permission from his family, copies were shared with the filmmakers. “They really wanted to understand each member of the boat, each character,” Cannon says. “People forget they weren’t just athletes. They were students.” Some of them were singers, some played instruments, a few worked on the Grand Coulee Dam in the summer and roomed together. “It was really fun to get to know each of them in a more in-depth way,” Cannon says. “It’s MGM’s story to tell, but it’s our legacy.”

* * *

The story and the legacy met up in summer 2022. Coach Callahan and a group of UW rowers had traveled to England for the Henley Royal Regatta on the Thames River. There, the four-oared men’s crew won the Visitors Challenge Cup with a record time. Sweetening their experience, about 25 rowers and coaches visited the movie set about an hour away. “When we got off the bus, I was blown away,” Callahan says. The sets looked exactly like structures on the Seattle campus. They even saw the Husky Clipper, which had been recreated in a workshop a few miles from where George Pocock grew up.

While the UW rowers were curious about the actors, the actors were just as excited to see the team, says Callahan. Once they had completed filming their scene, they headed over to the real rowers with questions. “The way they just embraced us, it was a real moment,” says Callahan.

One year later, a semi-trailer truck delivered an unassuming orange storage container to the UW campus in Seattle. Callahan and members of the rowing team waited in the parking lot as the lock was cracked open and the doors swung wide. Inside were props and pieces from the film. They found the replica Husky Clipper as well as racing pennants and photos, notes and letters that were used as props—all gifted from the filmmakers.

While eagles circled overhead on the warm summer day, the rowers gently lifted the reproduction racing shell out of its transport and carried it down to the Conibear Shellhouse, adding another artifact to the 1936 story.

* * *

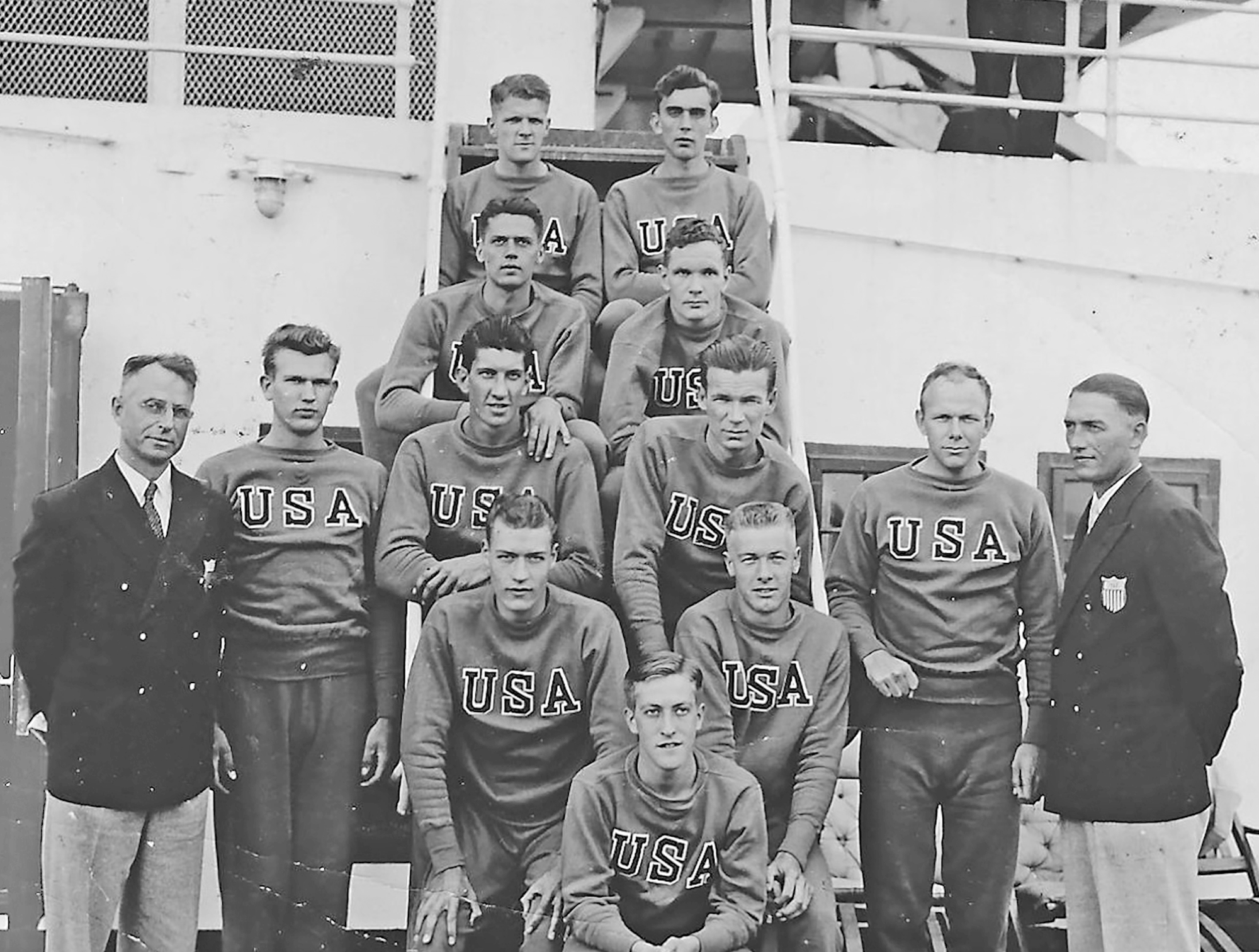

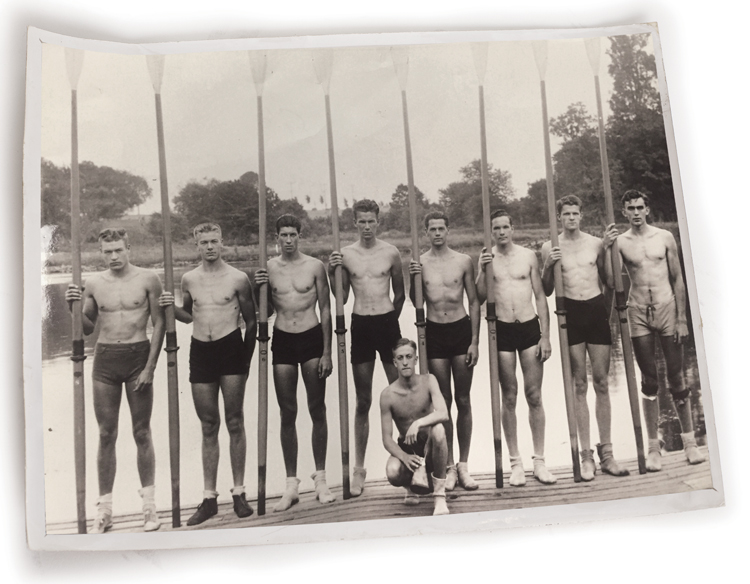

“The Boys in the Boat” from left: Don Hume (stroke), Joe Rantz, George “Shorty” Hunt, James “Stub” McMillin, Johnny White, Gordy Adam, Chuck Day, Roger Morris; kneeling, Bobby Moch (coxswain).

Today, the original Husky Clipper is polished and restored and floats upside down from the rafters of the Conibear Shellhouse dining hall. Student-athletes from nearly every sport pass beneath it each day. Visitors from around the world sometimes wander in hoping to catch a glimpse of it, often clutching copies of “The Boys in the Boat.”

Freshman rowers at the UW get the same thrill when they start their training beneath the Husky Clipper and hear the story of the 1936 crew. Tradition has it that they must learn two things: how to sing “Bow Down to Washington” and the names of all nine members of the team. “The story of the 1936 Olympic champions is central to becoming a UW oarsman,” Callahan says. UW rowing’s connection to the story has never faded, he adds. “It has been so central to us. Now everyone’s embracing it.”

Willman understands. She still gets chills in the old ASUW Shell House, which the University is working to restore and renovate. She feels the presence of the many rowers who housed their boats and oars there. “It’s almost like if you turn around fast enough, you can see them,” she says. “When you go into Pocock’s shop, it’s kind of the same thing.”

And it’s even more true when she stands beneath the Husky Clipper. “You look up into it and you see where each one of those guys was sitting, where they put their feet into the foot stretchers,” she says. “It makes your hair stand up on the back of your neck.”