Dinosaur dreams Dinosaur dreams Dinosaur dreams

Zeke Augustine, ’23, has sifted through soil for microscopic fossils and helped dig up a Triceratops. The Burke Museum has been at the heart of it all.

By Jamie Swenson | Photos by Dennis Wise | March 2022

On his 20th birthday, Zeke Augustine slung a 25-pound bag of plaster over his shoulder and trudged up a soft hillside in the triple-digit midday heat. It wasn’t how he’d expected to spend his birthday.

But Augustine, ’23, wasn’t complaining. The aspiring paleontologist was in the middle of a dream come true: his first dinosaur dig. Here in the remote eastern Montana portion of the Hell Creek Formation—possibly the best place in the world to find fossils from the Late Cretaceous—he was working with a small team of experts to uncover the fossilized bones of an oviraptorosaur, a category of beaked dinosaurs closely related to birds.

The team included Greg Wilson Mantilla, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the UW’s Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, and Dave DeMar, ’16, one of his former Ph.D. students and postdocs. For two days they had been carefully removing sediment from the animal’s fossilized pelvis, vertebrae and limbs, wrapping them in plaster for transport back to the Burke.

The exact identity of this dinosaur was unknown, and the mystery and excitement more than made up for the oppressive heat. Was this a “chicken from hell,” paleontologists’ nickname for the rare Anzu wyliei, which once could be up to 11 feet long and weigh 650 pounds? Or might it even be a new species? It was too soon to tell.

Suddenly, DeMar’s voice echoed from the other side of the hill: “Zeke! We found a claw!”

Time stopped for Augustine. The self-identified “bonehead” had been fantasizing all his life about a moment like this, and here it was.

But long before he ever got to dig up a dinosaur, he had to become one.

Zeke the T. rex

Obsessed with dinosaurs since childhood, Augustine joined the Burke-affiliated Northwest Paleontological Association at age 15. Soon, he’d landed a series of volunteer positions with the Burke—including dressing up in his own T. rex costume to greet patrons and sell memberships.

In addition to the philanthropic support that helps fund everything from field-research trips to community education events, the Burke’s volunteer program is central to its mission. Pre-COVID, some 400 volunteers worked in nearly every department. And now Augustine was one of them.

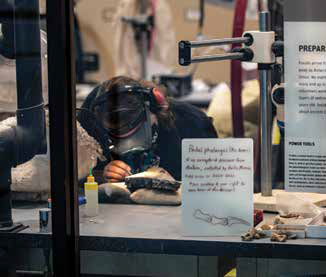

Happy to be doing anything adjacent to dinosaurs and those who studied them, Augustine slowly but surely made a name for himself at the Burke, while learning more about how fossils were studied and presented to the public. It was the Burke’s inside-out museum experience—with viewing windows where visitors can watch staff and volunteers prepare everything from bird specimens to dinosaur fossils—that really got him thinking.

“Zeke isn’t just incredibly knowledgeable about dinosaurs and prehistoric life. He’s passionate about sharing this knowledge with others,” says Emelia Harris, the Burke’s volunteer program manager. “When he saw fossil preparation being done in a visible way, it opened a whole new world of possibility for him.”

Someday, Augustine hoped, he would be on the other side of the glass. Or, better yet, out in the field digging up the fossils.

‘A highlight of my life’

Year after year, Augustine angled for a spot on a dinosaur dig. First, he was too young. Then the dig team was full. And next the dig was canceled because of the pandemic. Augustine pressed on with his studies, attending Cascadia College, transferring to the UW—and jumping at every opportunity to work with fossils.

He volunteered in curator Wilson Mantilla’s lab, sifting through sediment brought back from the Hell Creek Formation to find microscopic treasures: ancient crocodile teeth and tiny bits of lizards, salamanders and more. It required meticulous focus, but, says Augustine, “Any time I get to work with fossils is a good time.”

“Zeke earned his chance by his diligent work in the lab, so he was at the top of the list of undergrads.”

Greg Wilson Mantilla, Burke Museum paleontologist

As Augustine progressed in his research, Wilson Mantilla took note of his tenacity and his interest in working on theropods: meat-eating dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor. The curator had started a theropod tooth project with Dave DeMar (now a research associate at the Burke and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History), so he put DeMar and Augustine in touch. Soon, Augustine was recording measurements of Hell Creek theropod teeth. And when Wilson Mantilla was deciding who’d go to Hell Creek in 2021, one answer was clear.

“Zeke earned his chance by his diligent work in the lab, so he was at the top of the list of undergrads,” says Wilson Mantilla.

Before long, Augustine was on the sunbaked hillside in Montana, uncovering fossils—including that significant claw.

“I have a feeling it’s going to be a highlight of my life,” he says.

The other side of the glass

Augustine carefully glues together part of a Triceratops frill in the Fossil Preparation Lab.

If you visit the Burke Museum today, you might see Augustine behind the glass in the Fossil Preparation Lab, where he now volunteers as a preparator and carefully restores fossils brought in from the field. Recently accepted to the UW biology major with a minor in paleobiology, Augustine still beams with enthusiasm about the recent dig, when he spent several weeks helping uncover not just the oviraptorosaur but also three other dinosaurs, including a Triceratops.

Finding fossils is a highlight, but Augustine has relished every opportunity to connect with paleontology experts, whether in the field, at the Burke or in Wilson Mantilla’s lab.

“It’s helped me become a junior researcher myself,” says Augustine, who went into the dig thinking he probably wanted to be a paleontologist. Now he’s certain: “This year has definitely cemented that.”

As you peek through the window into the Fossil Preparation Lab, you just might see that significant claw from the Hell Creek dig. At four inches long, it is likely a hand claw. Researchers are still narrowing down the possibilities of what the rare—or entirely new—species of oviraptorosaur actually is, but Wilson Mantilla believes it’s the genus Anzu. Regardless of the final verdict, Augustine is awed that he was one of the first people to see it.

On that stifling July day, he had bounded over to where Dave DeMar stood. “I was initially like, ‘No way,’” Augustine remembers. “But then, sure enough, just sitting there in the dirt: ‘Wow. There it is.’”

Powering the Burke

Philanthropic support of the Burke Museum—Washington state’s oldest museum—powers its ability to curate stunning natural history and cultural exhibits; maintain a collection of more than 18 million biological, geological and cultural objects that are a boon for researchers around the world; and send faculty, students and volunteers into the community to conduct research and offer educational programs for learners of all ages.

When you contribute to the Burke Museum Annual Fund, you can help ensure that our community continues to learn, share knowledge and be inspired.