Art and resilience Art and resilience Chuck Close overcame struggles to become a renowned artist

Chuck Close, the 1997 UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, survived a spinal blood clot to paint again.

Chuck Close, the 1997 UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, survived a spinal blood clot to paint again.

He was big and clumsy and not very athletic. Because he was dyslexic, everyone considered him dumb and lazy. He was told to forget about college. He couldn't play sports because he couldn't keep up with his friends.

But that wasn’t the only pain Chuck Close had to deal with in his young life. His father, a sheet metal worker, plumber and on-the-side inventor, was always in ill health and moved the family from Monroe to Everett to Tacoma to Everett in search of civil service jobs with health benefits.

When Close was 11, his life became pure hell. His father died. His mother, a trained pianist who in the Great Depression gave up her aspirations for concert career, got breast cancer. They lost their home because of medical bills. His grandmother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. And Close, an only child, spent most of the year in bed with nephritis, a nasty kidney infection.

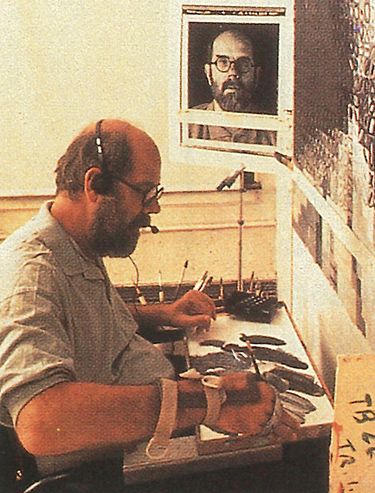

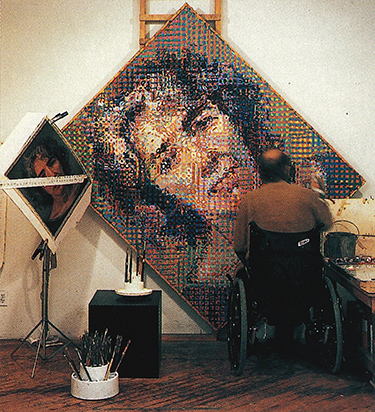

Chuck Close at work.

One thing did help him cope with the mind-numbing agony, sadness and misery: art.

He always liked to draw. At age 4, he knew he wanted to be an artist. At the age of 5, his dad made him an easel for his birthday and got him a set of oil paints from Sears. In an attempt to win friends and “get kids to be around me,” he also did magic and puppet shows. He drew and painted. People noticed.

Little did Charles Thomas Close know back then that he would indeed to go to college, graduating not only from the University of Washington in 1962 (magna cum laude) but from Yale as well. Now, at the age of 57, he is one of the true superstars of art. His works hang in the world’s most prestigious museums, he is considered by ARTNews magazine to be one of the 50 most influential people in the art world–and he is so big he turned down a major retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art because promises were broken. He chose the Museum of Modern Art instead. No one can recall an artist ever turning down the Met.

But this is much more than just the story of a local boy who made good. On Dec. 7, 1988, at the age of 49, Close was at the height of his career as a portrait painter when he was stricken with a spinal blood clot that left him a quadriplegic. Many thought his career was over.

As he came to grips with life in a motorized wheelchair, unable to move from the neck down, with little hope for improvement, his biggest fear was that “I was not going to make art. Since I’ll never be able to move again, I would not be able to make art. I watched my muscles waste. My hands didn’t work.”

But like the previous tragedies in his life, that didn’t stop him either. He not only returned to painting, but with a new style that has kept his place as one of the great American painters of our time. This month he will receive a new honor to add to the mantle of his Manhattan home–he becomes the 1997 UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, the highest honor an alumnus of the University of Washington can receive.

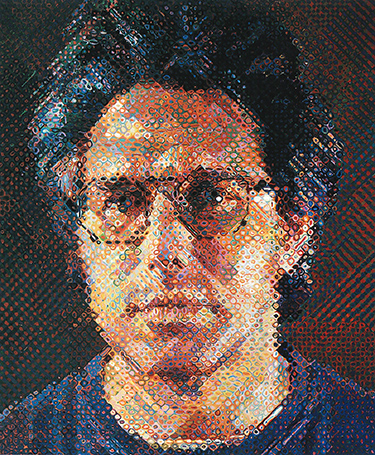

“Self-Portrait,” 1993 (detail)

When he left the UW for Yale in 1962, Close changed his style completely, dumping abstract paintings based on de Kooning in favor or “photorealist” portraits. He turned his back on abstraction in favor of photorealism because he wanted to “find his own voice” and not continue to do work similar to that of his UW mentor, Art Professor Alden Mason. It was a dramatic break: Photorealism is a painting style resembling photography in its close attention to detail, the opposite of abstract expressionism.

His work began to be shown in important New York galleries and at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the late 1960s. In the early 1970s, he was exhibiting in prestigious international exhibitions. By 1980, he was widely recognized as an important figure in contemporary American art. Today, publications surveying contemporary art history routinely discuss his painting and most modern art museums in the U.S. and Western Europe feature his work in their collections.

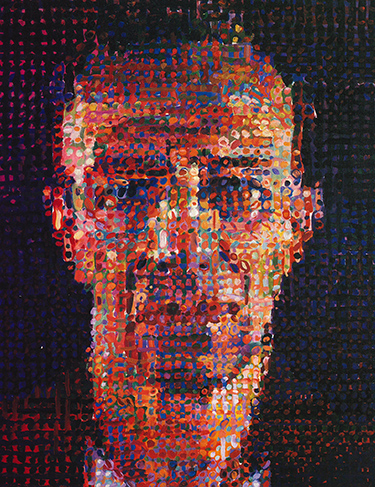

“Alex II,” 1989

He achieved his international reputation by demonstrating that a very traditional art form, portrait painting, could be resurrected as a challenging form of contemporary expression. His work has been superficially described as photo realist, “but is more revealingly positioned with the development of minimalism and process art of the 1960s and 1970s,” says Christopher Ozubko, director of the UW School of Art.

Close’s large, iconic portraits are generated from a system of marking which involves painstaking replication of the dot system of the mechanical printing process. The portraits he produces–utterly frontal, mural-size, and centered in shallow space–replicate the veracity of a photograph and undermine the objectivity of photography at the same time, critics say.

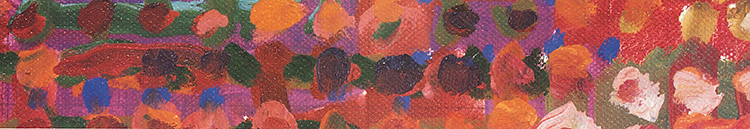

In the early days, though, his work was the complete opposite of realism. Upon his arrival at the UW from Everett Community College–which back in the 1950s was a feeder for the UW art program–he was influenced heavily by the now-retired Mason. They used to get thick paint by the gallon from a special dealer in Oakland, and churned out lots of abstract works. “It was the opposite of the precise work he is best known for,” says Mason. “We just glopped on tons of paint and followed the influence of de Kooning and other New York painters of the time. The brushwork then took a lot of energy, was emotional, hard work, full of anxiety and trauma because it was all improvisational. You had no idea what was going to turn out.

“He had talent and did nice work, but I had no idea he would turn out to be one of the great painters of our time.”

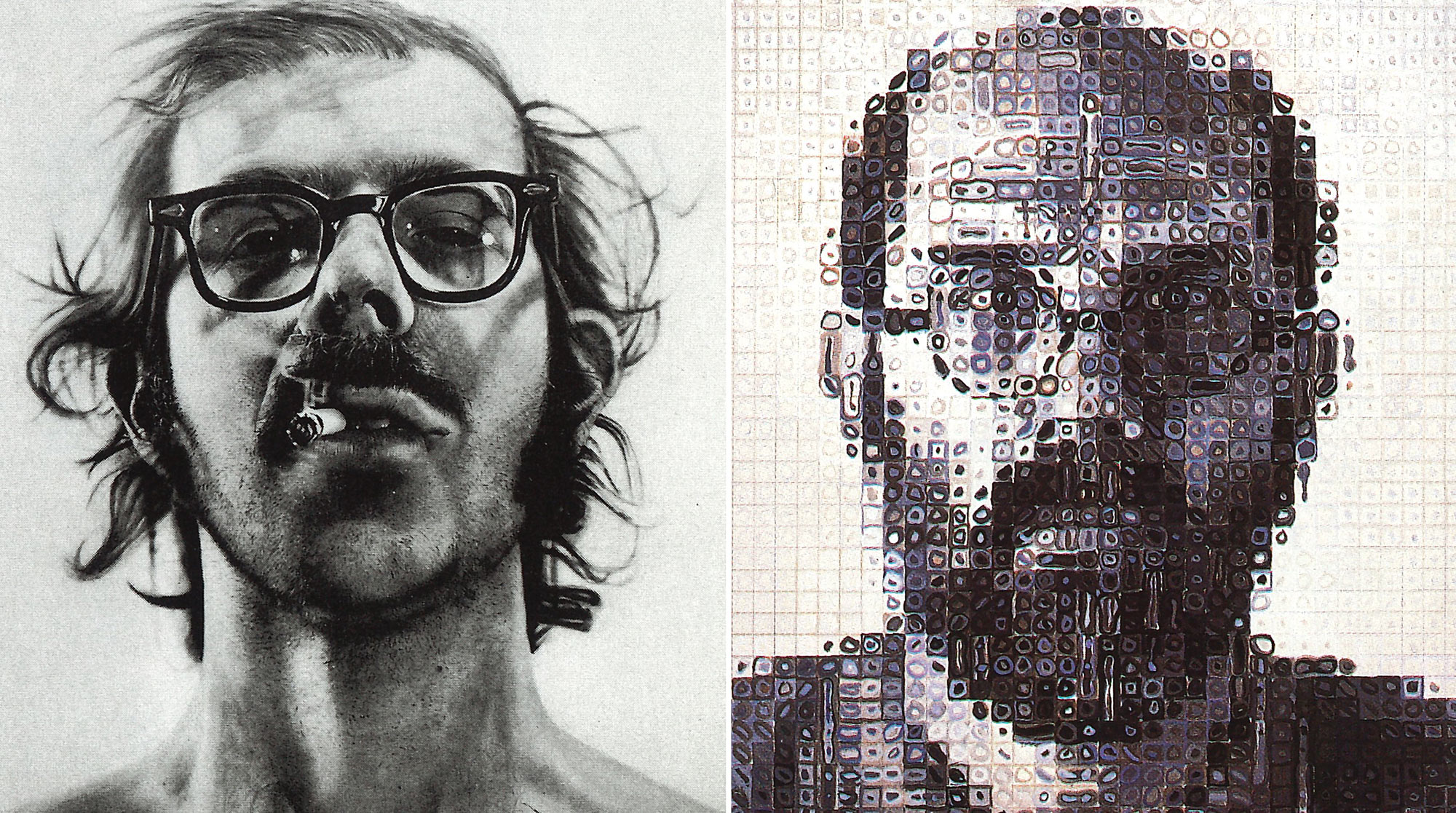

Close’s big break came when he went to Yale, first for the summer between his junior and senior years and then again for grad school. There, in search of his own voice, he says he “did all I could to put distance” from his earlier abstract work. So he flipped 180 degrees and started making photo realist works. He used exacting grids from huge, large-frame Polaroid pictures of his models, then recreated the image on canvas in color. It was a process he called “knitting.” He painted his friends, his family, himself, all in huge pieces that could cover an entire wall. His works depicted intense close-ups and details, every flaw on every patch of skin, mouth, nasal cavity. His famous 1968 self portrait shows him shirtless, hair askew, a smoldering cigarette off to one side of his mouth, a less than thrilled expression on his face.

His first large-format figurative painting was “Big Nude” (1967-68). Measuring 10 by 22 feet, she was too long to fit into Close’s studio unless her feet were folded. She was attractive without being exceptional, naked rather than nude, complete with stretch marks, tan lines, and pores. The model’s visible flaws were the marks of her personal distinction and Close’s candor. “I was trying to be very flat-footed and effect this translation (of a photograph) and not editorialize and not crank anything up for greater effect,” Close says. “But unconsciously, I couldn’t help but do it.”

“Alex II” (detail), 1989

He later moved into painting big heads, but his ideas began to change. At first, he was into objective detailing of his subjects in works that could compete with photographs for reality. Then he moved more into color and added some abstractness to the work, using the face as the frame. No longer did you see perfect “photo-mechanical” representations. ” The image had dissolution,” he says.

That continued in his work after his disability struck–and he has received even more acclaim.

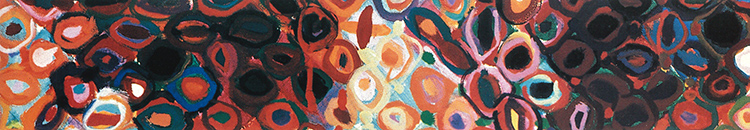

“It is the opposite of the precision work before his disability,” Mason says. “It is a great paradox. From far away the paintings look like passport photos but up close, they turn into this mosaic of dozens of different, individual paintings. How he makes it work is magic.”

“Eric,” 1990

The magic was evident early on in his life when he picked up a drawing pencil or paintbrush. “I was no good at anything else,” Close explains. “I could draw, and having an audience was interesting to me. That felt good.”

He took private art lessons, drawing and painting from nude models when he was eight. “I was the envy of my classmates,” he says.

That continued when he was in Everett.

“He was a premier student, and distinctive because of his chatter,” says Russell Day, who was chairman of the Everett art program. “He was very energetic, a show-off, and very verbal. He was a top student, but back then, in terms of creativity, he didn’t show it. He sure does now.”

Close went to the UW for the reputation of its art program and because he didn’t have any money. In the two years he was there, he shared a house with several other artists, and was known as an energetic, almost possessed painter. He was 6 foot 3 and weighed 210 pounds but hated one flaw: he was bald at 20. “Being bald when you are 20, you’re used to never looking the way you want to look, but I thought I had a decent body. I took pleasure in my body,” he says.

He also took great pleasure in his work. As a UW student in 1960, he was at a thrift shop near Lake Union when he came across a desecrated U.S. flag. He painted on it, and put on patriotic inscriptions, such as “E Pluribus Unum.” The painting drew little reaction while on display at the UW, or even at the Seattle Art Museum as part of the Northwest Annual show. He even won a prize for it. But when it was displayed at the Puyallup Fair, the American Legion objected strenuously. Some legionnaires tried to chop down the door to get at it, and the media coverage was substantial. “It was my 10 little minutes of fame,” he says.

“Eric,” 1990 (detail)

Over the years he achieved full-time fame, but his body started showings signs of betraying him well before that terrible day in 1988. Several times in his life, he experienced excruciating pain but doctors couldn’t find a reason.

Then came Dec. 7, 1988. He was in his Upper West Side apartment, alone. His wife, Leslie, was at work. Their two daughters, Georgia and Maggie, were at school. The mysterious pain came back and he dropped to the floor. The pain subsided but later, at an event at the mayor’s residence, he didn’t feel right. He made an award presentation, then promptly left for a nearby hospital.

The doctors didn’t know what was going on. He had a long, violent convulsion, his hands and legs flailing about. He had to be held down, and then he stopped moving–yet never lost consciousness. The doctors thought it was a cardiac problem. Days later, he was transferred to the NYU Medical Center. Close was in sorry shape–only the top quarter of each lung worked. His lungs were suctioned every two hours, he could barely breathe, his diaphragm stopped working, his bladder didn’t work, his limbs were numb.

Eventually, doctors discovered a blood clot in his spinal column. It was high up in his neck and damaged the spinal cord, causing his paralysis. Had it been an inch higher, he would have died. An inch lower, and he would have minimal paralysis.

Chuck Close at work on “Elizabeth,” 1990.

“Have you ever been in a car wreck, with the car spinning out of control,” he asks. “You know that strange eerie calmness that takes over as you almost go into slow motion? You turn the wheel this way, that way. Only when it’s over do you fall apart and go into shock. This was an attenuated, drawn-out case of that, where many days I experienced a profound calmness, eerie even to me.”

In early 1989, he began a grueling rehabilitation program but was feeling hopeless. Then his wife insisted that Close get back to painting. At first, he held a brush between his teeth and he could control it enough to paint. “I suddenly became encouraged,” he says. “I tried to imagine what kind of teeny paintings I could make with only that much movement. I tried to imagine what those paintings might look like. Even that little bit of neck movement was enough to let me know that perhaps I was not powerless. Perhaps I could do something myself.”

Later, he regained some movement in his upper arm, and his therapists fashioned a hand split onto which they could tape a paint brush. At first, he used gloppy poster paint. With great effort, Close drew a primitive grid on the cardboard. He could barely move the upper portion of his arms. He moved the brush around in the paint for as long as he could bear it–usually one or two seconds–and he then attempted to daub it into the space of the grid he made.

It was the birth of a new style that has earned Close fame and fortune equal to what he enjoyed prior to his tragedy.

He was making lozenge shapes with the paint brush strapped to his hand. “I saw that each grid was in fact a tiny painting,” he says. “I thought about making little teeny paintings. I’ll paint in my lap little two-inch paintings backed with Velcro and then they’ll all go together on the wall like a big jigsaw puzzle. It will eventually build a big picture. I didn’t want to lose the scale of my work. This would address the problem of how I’d build a big painting. I’d paint little pictures and then have assistants mount them on the wall.”

His work blossomed from there. His paintings this time were much more colorful and the image was much softer. “This was the path I had been on, this dissolution of the image. I realized that all I had done was catch up in my work with where I had been,” he says.

His new system of painting added a wide range of brilliant color, and, according to Roger Angell writing in The New Yorker, “a ravaged artist has become, in a miracle, one of the great colorists and brush wielders of his time.”

His life is a struggle but it has its rewards. In his custom studio, the boy from Monroe whom no one thought would amount to anything paints dazzling, huge works from his wheelchair, enthralling art enthusiasts and critics alike.

At top: “Self-Portrait,” 1968 (left) and “Self-Portrait” (1993).