Rehashing history with pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman Rehashing history with pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman Rehashing history with pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman

We posed him a sprawling series of Seattle-themed questions. He passed.

Interview and lead photo by Quinn Russell Brown | August 24, 2018

Chuck Klosterman, author of 10 books and a former columnist for The New York Times Magazine and ESPN, stopped by the University of Washington to read from his latest collection of essays, “X: A Highly Specific, Defiantly Incomplete History of the Early 21st Century.”

As someone who moved to Portland in 2017, from Brooklyn, how strongly do you believe in the idea of a Pacific Northwest identity? A lot of people I meet seem to think one exists.

I would say that I do think that’s true, but I’m not sure they would agree with my read on it. The thing I’ve noticed living here is that people really prioritize being earnest. At first, I just thought people here weren’t sarcastic. But now I think it’s a choice—that they like to view their life as separate from the way life is perceived on the East Coast, and in the Northeast specifically.

Seattle sports fans politely stand up to hatred at a soccer match. (Photo: Gregory Mauch)

There seems to be this desire to look at living in the Pacific Northwest as the best possible life. People in other cities argue that their city is the best city. People in New York and Chicago and Boston think this. But around here, people seem to think the lifestyle you can live here is superior. In most parts of the country, the first thing people will tell you about is their job. I find that here, the first thing people tell me is what kind of mountain bike they own.

People here care about sports less than they do on the East Coast. I feel like as you move across the U.S., the interest in sports slowly and incrementally decreases—which is good in a way. It seems like an insult to the fan base or whatever, but for people in New York and Philadelphia and Boston, it almost seems like sports are too big a part of their life. There’s always the chance that the success of a sports team could lead to a riot. I feel like there’s nothing the Trail Blazers could do to start a riot, which is one of the reasons I like living here.

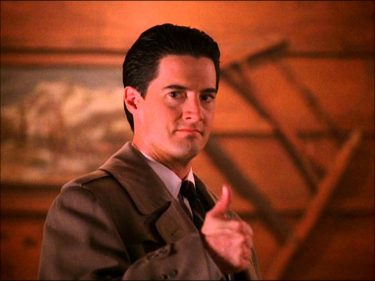

I’ve got a few rounds of either/or. I’m going to give you two graduates of the University of Washington, and you tell me which one is more culturally important—whatever that means to you. First up: Patrick Duffy, who depicted Bobby Ewing in “Dallas,” or Kyle MacLachlan, who played Special Agent Dale Cooper in “Twin Peaks.”

When you said Patrick Duffy, I thought, “It’s going to be hard to beat this.” But I guess it would be Kyle MacLachlan. I feel like Patrick Duffy is really known for one iconic role, while MacLachlan was in “Twin Peaks,” but he was also in that terrible version of “Dune.”

Kyle MacLachlan as the cool, charming and unflappable Special Agent Dale Cooper in “Twin Peaks.”

Mark Arm, lead vocalist for the groups Green River and Mudhoney, or Kim Thayil, lead guitarist for Soundgarden.

Mark Arm is more important to Mudhoney than Kim Thayil is to Soundgarden, although Kim Thayil is pretty important. They both went to UW? I didn’t realize that. My preference is Soundgarden, so I guess I will say Kim Thayil, but it’s very close. I would almost want to know who had the higher GPA. My assumption would be that Mark Arm majored in English, and Kim Thayil majored in either philosophy or science. (Editor’s note: Arm majored in English, and Thayil majored in philosophy.)

Rainn Wilson, most known for one incredibly famous role–Dwight on “The Office”—or Joel McHale, who starred in “Community,” “The Soup,” and a current Netflix show. (Editor’s note: McHale’s Netflix has since been cancelled.)

Joel McHale also played football for UW.

Joel McHale at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. (Taylor Jewell/Invision/AP/Shutterstock)

Right. So the longer entertaining career seems to be Joel McHale, but the defining role belongs to Rainn Wilson.

True, although “Community” was about four times funnier than “The Office.”

Oh, wow! Bold statement.

Well, I like “The Office,” but I don’t think there have been many sitcoms in the past 20 years that have been as good as “Community” when that show was good. When that show was at its apex, it almost made me feel bad. It was so good that I was like, “Why am I even trying to write about pop culture?” So, as a consequence, I’m giving Joel McHale the accolades.

Dwight Kurt Schrute III, played by Rainn Wilson, wearing his hydration backpack on the season 7 premiere of “The Office.” (Photo: NBC)

Jazz saxophonist Kenny G, or jazz guitarist Larry Coryell.

If you’re looking at cultural importance, it’s gotta be Kenny G—for no other reason than that he has become a shorthand way to complain about jazz. Now that’s a weird thing to be famous for, but when does something become culturally significant? When it becomes significant to people who don’t care. Everyone knows who Kenny G is.

Barefoot Man: Sanpaku by Larry Coryell

My thought would be that people who listen to jazz would say Larry Coryell, and people who don’t listen to jazz would say Kenny G.

My understanding of jazz is limited, but my assumption is that Kenny G must be a technically proficient musician, and that the things people don’t like about him are the style he plays in and the look. They’re both technically proficient, but something made him this famous—and it wasn’t just being named Kenny G.

Two undersized, underdog NBA players: 2017 MVP candidate Isaiah Thomas, or three-time Slam Dunk Contest winner Nate Robinson.

Well, Isaiah Thomas is a much better player, even though he’s had some struggles as of late. Nate Robinson was sort of a… I hate to call a guy a gimmick who had a real career, but he was like a little more offensively gifted Muggsy Bogues. He kind of played the role of Kevin Hart during the NBA All-Star Game. I would go with Thomas. He could still have a pretty meaningful career if he goes to the right place.

Isaiah Thomas photographed at his UW jersey retirement in February, 2018 (Photo: Quinn Russell Brown)

Does it impact your decision that Nate was a 2017 Venezuelan League Champion?

He was a league champion, but was he the best player on the team? For all we know, he could be one of those guys just chasing rings—but he’s really chasing it, going to Venezuela.

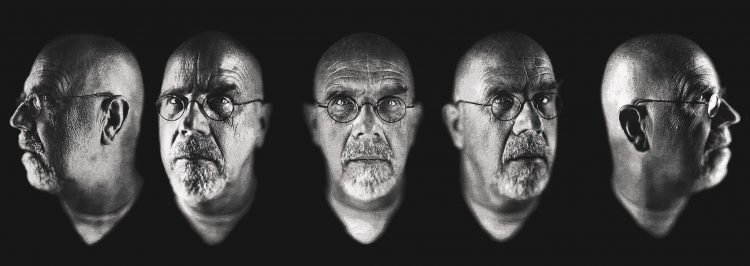

Let’s move on. Inside of your name, Chuck Klosterman, is the name of perhaps the most famous UW alum in the art world: Chuck Close. Recently, he’s been accused of sexual misconduct and abuse of power. How should we grapple with a great artist who misbehaves?

I often feel very nervous discussing these things because I’m just talking about ideas, but when people see you talking about ideas that make them uncomfortable, they attack the person. But let’s say Chuck Close rescued 18 people from a fire. Pretty amazing, particularly because he’s in a wheelchair, but let’s say he did that—rescued 18 people from a burning building. Would that recontextualize how we consume his art? For me, it would not. I would think that is something else about his life that is significant, but that is ancillary to the reason we care about who he is.

“Self Portrait/Five Part,” a 2009 piece by Chuck Close, is part of a traveling exhibition that was hosted by the Henry Art Gallery from November 2016 to April 2017.

My natural inclination is to feel that way about transgressive acts: That these are things that inform us about the individual. They do not necessarily inform the art—unless you make the choice to inject that knowledge into the art, and sort of see something different coming back at you. Which is an acceptable way to do criticism.

When I began as a critic in the ’90s, there was a real emphasis on the ability to separate the art from the artist, and it was perceived as something a lot of consumers could not do. Now it’s completely reversed: You’re not supposed to do that at all. And, in fact, people get very angry if you do. There are people who would be very angry with me for thinking that about Chuck Close. But that creates a lot of interesting questions: What do we do with art created by people we know nothing about?

In wake of sexual misconduct allegations against Chuck Close, museums wrestle with separating the art from the artist https://t.co/pvnZk6XRIp

— The New York Times (@nytimes) January 28, 2018

Northwestern University gave an honorary degree to Bill Cosby, and a lot of people are like, “We need to take that away from him.” And that’s very understandable, because the reason you give an honorary degree is because you see that person as almost a personification of what your institution is trying to do. So if the person is a terrible person, that’s totally justified.

Now, should someone teaching a class on the history of television specifically not talk about “The Cosby Show” when discussing race in the 1980s? That seems like a mistake to me. There’s got to be some ability to differentiate. Are we honoring this person because we like them, or are we considering this person because the work they did was meaningful?

Klosterman discusses darkness in “I Wear the Black Hat: Grappling with Villains.”

Here’s a more clear-cut villain: 1972 UW graduate Ted Bundy. Bundy was a notorious serial killer who you wrote about in your book “I Wear the Black Hat.” You refer to him as an exception when it comes to serial killers, in the sense that society has given him a pass in a lot of ways. You credit that to good looks and charisma, writing: “Bundy is best known for being the handsome serial killer.” What about Bundy made you focus on him in the book?

In that book, I was talking about the arbitrary nature of how we view villains, and the way we construct villains with a criteria that’s really ancillary to the crime itself. That’s in the section where I’m talking about Bill Clinton, and how a lot of Bill Clinton’s transgressions were seen differently because he was a very good-looking, charismatic person. Now, that said, I wrote that before all the #MeToo stuff happened. I think the perception of Bill Clinton has already changed significantly. But at the time, it was seen as, “Huh, it’s weird that he’s doing this,” but it’s not weird in the way that we would later look at Harvey Weinstein or Woody Allen, who are seen as unappealing people.

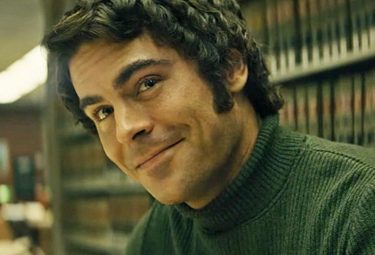

Hollywood heart throb Zac Efron as cold-blooded killer Ted Bundy in the 2019 Netflix movie “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile.”

Unlike so many other serial killers, people do not see Ted Bundy as repulsive. They see him as perverse and attractive. When you talk about someone like John Wayne Gacy, the first thing that comes up is, “He used to dress like a clown to trick these children into his lair,” and it comes across as ultra-creepy. And when you talk about Jeffrey Dahmer, he’s like this sociopath.

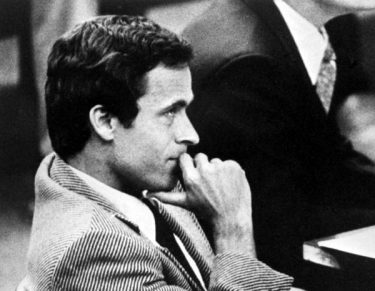

The real thing: Convicted serial killer Ted Bundy in court, circa 1979. Bundy graduated from the University of Washington seven years earlier.

But when people talk about Ted Bundy, the first thing they discuss is that he was a really good-looking guy who women seemed to like. It really has shifted the way we look at him as a murderer, because if you look at the crimes he committed, they are as repulsive and sick as any other serial killer. If I remember, when the judge is sentencing him to death, he says, “You would have been a good lawyer, but you went the wrong way in life.” That’s a weird thing.

But I’ll say this: Among UW graduates, I’ll definitely put Rainn Wilson above Ted Bundy. If that had been a comparison, real easy: Rainn Wilson kills Ted Bundy.