Taste and time Taste and time Taste and time

Culinary scholar Michael Twitty shows how our history is baked into our food

By Shin Yu Pai | Photo by Johnny Shyrock | December 2023

Michael Twitty, culinary historian and renowned food blogger, is the first Black author to garner the James Beard Award for Writing. Known for weaving together memoir, genetic research, historic interpretation, nature study, heirloom gardening and interviews, Twitty connects food, ancestry and cultures.

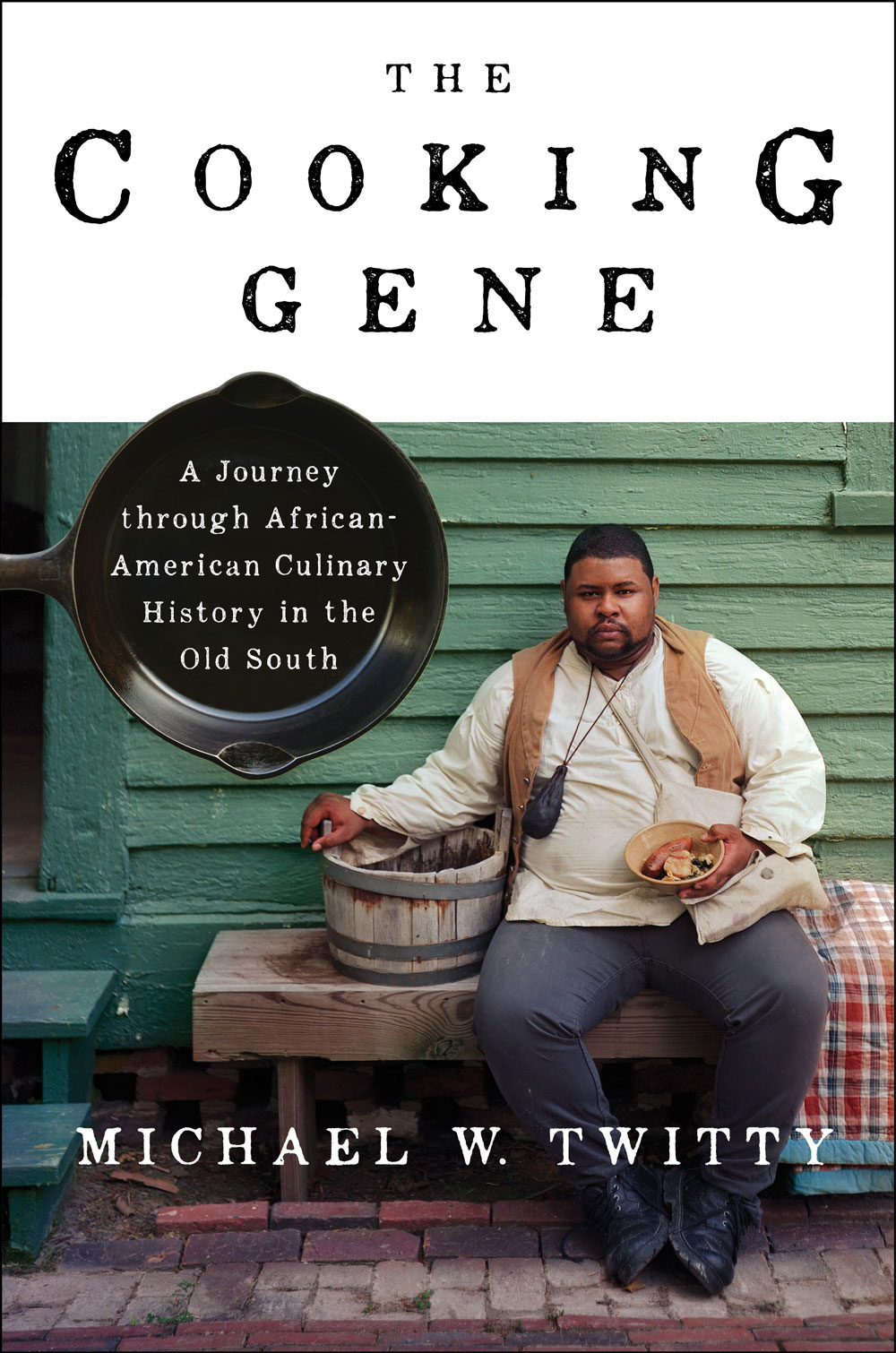

Culinary historian Michael Twitty joins UW Public Lectures to discuss exploring his identity through the food traditions of Africa, African America and the African Diaspora. He won the 2018 James Beard Foundation Book Award for “The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South.”

His book, “The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South,” traces Twitty’s African American ancestry through food from Africa to America to examine the tensions surrounding the origins of soul food, barbecue and all Southern cuisine. The author is coming to Seattle Jan. 24 to share his experience and insights as part of the UW Public Lectures series.

Twitty started writing “The Cooking Gene” during the Obama administration and published it during Trump’s first year in office. The changing political circumstances prompted his own reassessment of racial legacies at a moment of national transition.

Over a recent phone call, Twitty described his memoir as about being vulnerable and “challenging yourself and your neighbor to acknowledge what being American really is. The fact that we’re interdependent.”

“Twitty’s book helps the reader to recognize fully the legacy of slavery that hangs on the American polity as an unpaid debt,” says Ann Anagnost, the professor of anthropology who nominated Twitty for the UW guest lecture. “It is a work that both challenges our understanding of the past while also offering us a vision for racial healing.”

As part of his talk, Twitty will touch upon his newest book, “KosherSoul,” an uncommon exploration of African-Jewish cooking. He uses interviews as a dialogue between diasporas to trace centuries-old Black Jewish lineages in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, South America, Europe and historic Black Jewish communities across the U.S. In reflecting on both of his books for the Seattle audience, he will blend various stories of migration and how those journeys tie back to food.

Twitty’s signature literary style reflects his resistance to writing about food and culture with a stereotypical approach. Rather than limiting himself to writing about foodways through the lens of trauma, he embraces intellectualism.

“I wanted to be a nerd like everyone else,” he says. Growing up with books, movies and documentaries, he found himself wanting to bring together everything that shaped him. “It’s about that weaving,” he says. “Why do only white girls get to write ‘Eat, Pray, Love’?”