For some, 1970 was the year that the Beatles broke up. Or the year of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. But for Steve Swenson (pictured above) it was the year of the telephone pole. It started in boyhood with Swenson inhaling climbing accounts by mountaineers including Sir Edmund Hillary, the New Zealander who, with Nepalese Tenzing Norgay, first climbed Mount Everest in 1953. Then, when he was 14, Swenson climbed to the top of Mount Rainier with his Boy Scout troop. It whetted his appetite for more. That’s how the ordinary Doug-fir telephone pole at the end of the driveway of his family’s south Seattle home morphed into a “rock cliff.”

Swenson, ’77, took pitons (metal spikes climbers use to progress up a rock) that he had ordered by mail and jammed them into the pole as he climbed using a technique he’d learned from a book. Soon, he was 15 feet up the pole and enjoying the view of his neighborhood. The fun ended abruptly when his dad, a Boeing engineer, came home from work in his old brown Studebaker pickup. A spirited conversation between father and son ensued with the elder Swenson beginning the chat by asking, “What kind of a stupid stunt is this?” Swenson convinced his father that the safest course was to “summit” the pole; tie a loop of nylon webbing around the wooden crossbar bolted to it and then rappel to the ground. Swenson considered the experiment worth the punishment and the pole became a foretaste of the joys to come.

These formative experiences would propel Swenson on what has now become a 45-year climbing journey. Swenson has climbed all over the world including in India, Pakistan, the Argentine Patagonia, Nepal and many more countries. In 2012, he and his partners made the first ascent of Sasser Kangri II (7,518 meters)—the second highest unclimbed mountain in the world for which they were awarded the prestigious Piolet D’Or award (French for the ‘Golden Ice Axe’), for the most significant climb of the year. He has summited K2 and Everest without oxygen and is a former president of the prestigious American Alpine Club.

Fred Beckey

As illustrious as Swenson’s career has been, he’s just one part of a rich UW climbing legacy. The Pacific Northwest’s most storied climbing legend, Fred Beckey, ’49, who also got his start climbing with the Boy Scouts, has more first ascents than any other climber in the world. He has climbed and named many of the peaks in the North Cascades. Beckey is also the foremost author of guidebooks about climbing in the Pacific Northwest. Becky, who is 90 and still climbing, writing and giving presentations about his experiences, shunned the trappings of conventional life devoting himself single-mindedly to his climbing passion. In fact, it appears that a degree in business from the UW may be the single most conventional act of Fred Beckey’s life. (He said in December, after returning from a climbing trip to China, that he enjoyed his time at the UW, especially “the Hub and the breaks.”) He has become a little like Bigfoot, a fabulous creature with many unconfirmed, yet hopeful sightings by Pacific Northwest hikers.

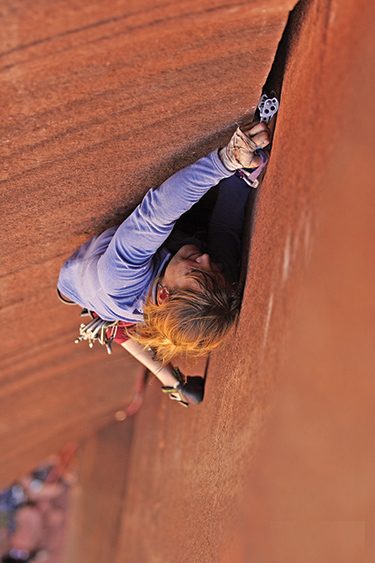

Kitty Calhoun climbing.

Like Beckey, Kitty Calhoun, ’93, has devoted her entire existence to climbing. Material concerns recede in the quest for the next excellent adventure. A self-described former debutante and Southern belle, Calhoun lived out of her Subaru for seven years. Tragically, this lifestyle presents terrifying risks as well. Chad Kellogg, ’93, ’01, was killed Feb. 14 in a climbing accident in Patagonia. Interviewed via email a few weeks before his death, he told Columns, “Although I own a couple of houses, in order to earn enough money to be on expeditions eight months a year I need to live in a tent 250-plus days each year at this point in my life to live my dreams.” Kellogg, 42, set the speed record on Mount McKinley (Denali) in June 2003, in 14 hours, 26 minutes. He also set the roundtrip speed record on Rainier in August 2004 at 4 hours, 59 minutes.

Others, such as Swenson, Brent Bishop, ’93, and Thomas Hornbein, ’57, pursued careers in engineering, business and medicine, respectively, and managed to have families as well. Ed Viesturs, ’81, and Calhoun are “professional climbers,” each sponsored by a company that sells climbing gear and apparel. Viesturs is a brand ambassador for Eddie Bauer’s First Ascent Line and Calhoun represents Patagonia. Kellogg was a brand ambassador for Outdoor Research.

Thomas Hornbein, a physician, followed a different path. He spent 43 years in the Departments of Anesthesiology, and Physiology and Biophysics, serving as chair of Anesthesiology from 1978 to 1993. He also conducted significant research on the effect of oxygen deprivation and the altitude effect on the human brain. Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld, ’59, were among the climbing party that saw the first American ascent of Mount Everest; the two climbed what was, and still is, a difficult route up Everest, the West Ridge. Hornbein told Outside magazine, “When we went up there we didn’t have any idea what we were getting into. We had one Indian Air Force photo—they flew over Everest right after it had been climbed in 1953,” he says.

Tom Hornbein

The magazine went on to call that climb one of the greatest achievements in American mountaineering. (Unsoeld died during an avalanche on Mount Rainier in 1979.) Hornbein’s book, Everest: The West Ridge, is a fascinating account of this climb. Hornbein, now 83, describes himself as “an amateur climber.” Some amateur. He still climbs, albeit more slowly, in Rocky Mountain National Park with Jon Krakauer, author of Into Thin Air, and other younger friends who he says are “patient.”

Calhoun, who received her master’s degree from the UW Foster School of Business, lives in Moab, Utah. For the past 15 years she has volunteered with Chicks with Picks, an organization that promotes self-reliance by teaching technical climbing skills to women. Calhoun is the first woman ever to reach the top of Makalu, the fifth-highest mountain in the world, and the first American woman to summit Dhaulagari, another high Himalayan peak. Of late, Calhoun is on a new mission: Speaking to people about climate change. “The Himalayas are experiencing the greatest effects of climate change of anywhere in the world. There will be floods and then there will be drought. I have seen it as an alpinist. There are climbing routes that will never have a repeat because the ice is gone,” she says.

Viesturs is one of the most well-known American climbers, not just for his climbing achievements. He has successfully reached the summit of the world’s 14 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen, the only American to do so and has written several books about his adventures on the world’s highest peaks. His latest book, The Mountain: My Time on Everest, was published by Touchstone last fall.

> Read an excerpt from Viesturs’s book.

Brent Bishop

For Brent Bishop, ’93, climbing Mount Everest was a family affair. His father, Barry Bishop, was on the famed 1963 American expedition up Everest where he and his partner followed the South Col route of the original 1953 climb. Brent reached the summit of Everest in 1994—making them the first American father and son to reach the peak—and again in 2002. The younger Bishop co-founded an organization devoted to cleaning trash off the slopes of Everest. Bishop followed in his father’s footsteps for a National Geographic Society film titled “Everest, 50 Years on the Mountain,” celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first ascent. Bishop is one of three sons of these original explorers to take part in the documentary.

> Read Bishop’s essay on following in his father’s footsteps on Mount Everest.

Today, the UW is still a magnet for those who seek adventure in the mountains. The UW Climbing Club has been active for decades and now has about 100 active members. Although the group doesn’t have formal meetings, members can be found on Wednesday evenings enjoying pub night at the Big Time Brewery on the Ave.

There, the next generation of Husky climbers meets to talk climbing and to plan trips over a brew or two. There is no doubt that some of them will keep on going beyond the Cascades to summit other mountains in the world. Many records have already been set by Huskies but future generations will push the limits of mountain exploration. It’s part of their heritage as Huskies.

Just before this issue of Columns went to press, a stark reminder of the extreme dangers faced by climbers was delivered as news of Chad Kellogg’s death spread. He was struck Feb. 14 by a falling rock as he descended Mount Fitz Roy in the Patagonia region of Argentina, killing him instantly.

Kellogg was born in Omak, Wash., in 1971. He spent several years of his childhood in Kenya as his parents served as missionaries, before returning to the Northwest, where he began climbing in this early teens. His career was marked by accomplishment, as he set records for climbs on Mount Rainier and Denali.

Kellogg was also no stranger to heartbreak. His wife Lara-Karena Kellogg died during a descent of an Alaskan peak in 2007. Soon after, Kellogg was diagnosed with colon cancer. Since, Kellogg’s only brother and several other relatives, along with his close climbing partner, Joe Puryear, have also died. Kellogg had received grants to scale two unclimbed peaks in Nepal later this year.

Brent Bishop told The New York Times that Kellogg “… was a cardiovascular machine. He was really able to suffer. He kept getting stronger. I think we were really robbed of seeing what this climber was going to do.”