The historian of Seattle hip-hop

The historian of Seattle hip-hop

The historian of

Seattle hip-hop

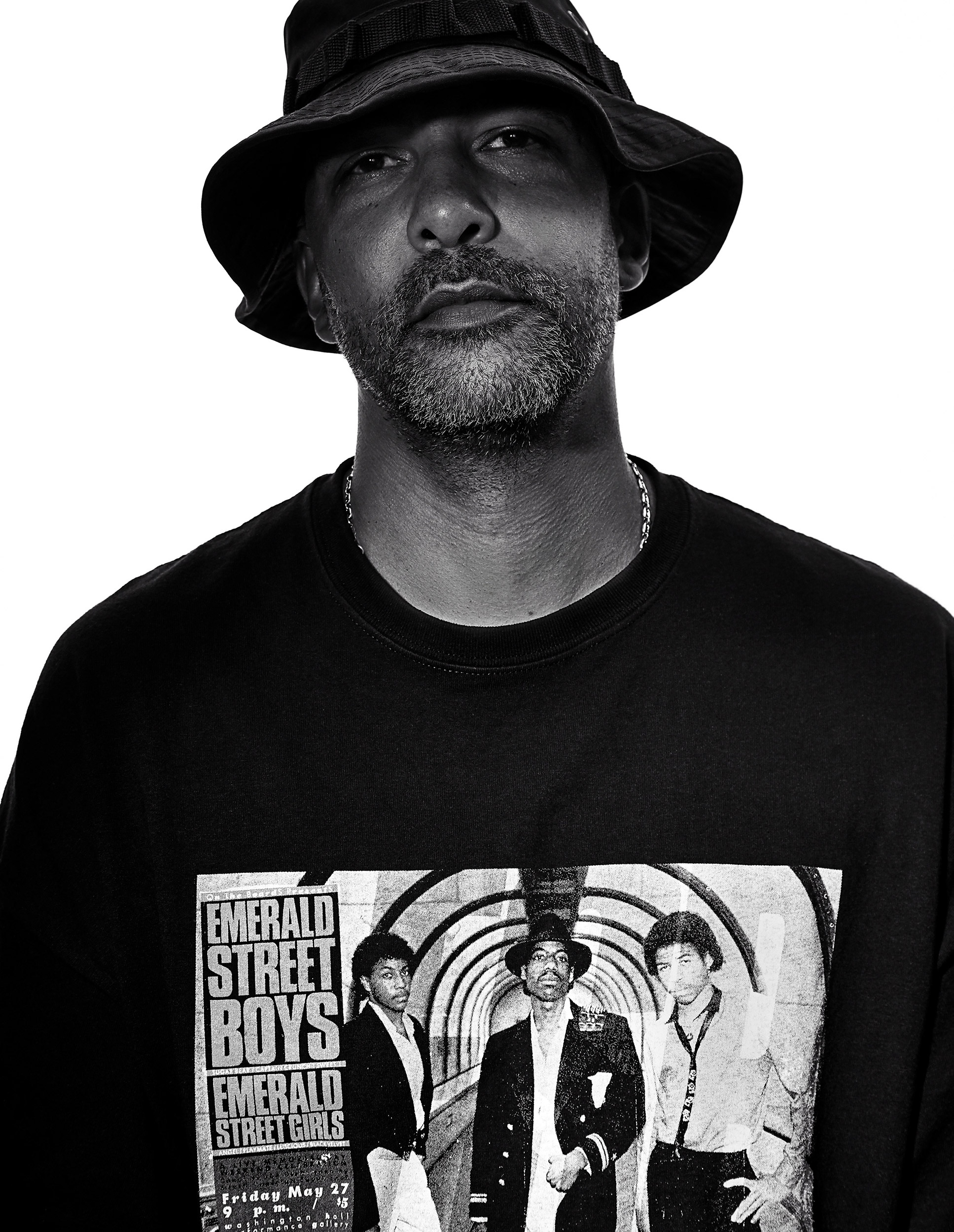

Daudi Abe, author of an upcoming book on Northwest rap, tells us what makes the local scene so special.

Story by Hannelore Sudermann | Photos by Quinn Russell Brown | September 2020

In 1979, when Daudi Abe was 9, his father took him to Dirt Cheap Records and set him loose to explore. After a few minutes in the Central District store, Abe came up to the cashier carrying a 12-inch vinyl single with the words “Sugar Hill” across the top. “I just liked the sky-blue cover,” he says.

The cashier told him he was buying “Rapper’s Delight,” the hot new single from New York. At home, the record delivered a familiar sound—an interpolation of “Good Times,” by Chic that young Abe recognized from the radio. But it was the talking in the song that transfixed him: “So after school/I take a dip in the pool/Which is really on the wall/I got a color TV/so I can see/The Knicks play basketball.”

“That record changed my life,” says Abe, ’04. “The things they were talking about just really drew me in.” Forty-one years later, Abe pays homage to the hip-hop art form in his latest book, “Emerald Street: A History of Hip Hop in Seattle.” The discovery of that Sugar Hill single primed Abe for Seattle’s burgeoning hip-hop scene, which was just heating up as he became a teenager.

Today Sir Mix-A-Lot is a legend, but in the early 1980s, the artist was performing in the gyms of Boys & Girls Clubs in South Seattle and the Central District. Mix-A-Lot’s performances took on mythical proportions because he was doing everything, says Abe, a historian and humanities professor at Seattle Central College. “He was a DJ, he was a rapper, he had computers—he had a full-on show.” FreshTracks on radio station KKFX (KFOX, 1250 AM) on Sunday nights was the first all-rap radio show on the West Coast and Mix-a-Lot, with songs like “Square Dance Rap,” quickly became the most requested artist.

Ice Cold Mode – “Union Street Hustlers”

As Abe reached high school, Seattle’s hip-hop scene went national. Mix-A-Lot was producing his own music and, with DJ Nasty Nes Rodriguez, Greg Jones and the DJ then known as Ed Locke, he started Nastymix Records in 1985. “It was a blueprint of how a minority-owned rap label can produce local music with global appeal,” says Abe. With Mix-A-Lot’s music, the Seattle label made its mark. “ ‘Swass,’ in 1988, and ‘Seminar,’ in 1989, went platinum and turned the rap music industry on its head,” says Abe. It showed the world that great hip-hop could come from anywhere. “It sent a message to people outside of New York and L.A. who were struggling with legitimacy conflicts.”

Witness to the rise of the city’s lively and multicultural hip-hop scene, Abe explores how the movement influenced the Northwest from its start with groups like the Emerald Street Boys in the late 1970s to today. With the help of interviews of many of the region’s artists, he captures the stories of Seattle’s most famous performers, including Macklemore, graffiti artists, groundbreaking record producers, and the Massive Monkees, the world-champion breakdancing crew. “Our regional isolation gave license to artists and musicians so they didn’t have to copy anybody,” Abe says. “They could just be themselves.”

In the years following the city’s rise to national fame, Seattle’s hip-hop culture continued to grow, but stayed true to its Northwest approach. In 2002, while Abe was working on his UW doctorate in education, undergraduates Saba Mohajerjasbi, ’03, (DJ Sabzi) and George Quibuyen, ’13, (MC Geologic) formed the Blue Scholars. Rooting their points of view in their own experiences and in the Pacific Northwest, the duo tackled topics like racism and American imperialism from a multicultural perspective.

In his book, Abe also explores the broader themes of race and diversity as they relate to hip-hop: the ’80s crack epidemic, gentrification, and telling details like the years of Black people getting arrested for selling marijuana at the intersection of 23rd and Union, where there is now a white-owned cannabis shop. “The story of hip-hop is an underappreciated aspect of local culture,” says Abe. Capturing that story was one of his driving motivations for the book. “It’s not just about music history,” he says, “it is about Seattle history.”

“Emerald Street,” published by the University of Washington Press, is due out in November.

Below, Dr. Abe has curated a playlist of Seattle hip-hop music, starting with The Emerald Street Boys (the group pictured on his favorite T-shirt). Hit play and the mixtape will spin.

1. Emerald Street Boys – “The Move”

2. Sir Mix-A-Lot – “Posse On Broadway”

3. E-Dawg – “Drop Top”

4. Ice Cold Mode – “Union Street Hustlers” (featured above)

5. Sharpshooters – “Pork Pie Stride”

6. Digable Planets – “La Femme Fetal”

7. DMS – “Sunshine”

8. Ghetto Children – “Equilibrium”

9. Laura “Piece” Kelly – “Central District”

10. Blue Scholars – “Joe Metro”

11. Jake One – “Home”

12. THEESatisfaction – “Queens”

13. Macklemore & Ryan Lewis – “The Town”

14. Draze – “The Hood Ain’t The Same”

15. Gifted Gab & Blimes Brixton – “Come Correct”