Rayburn Lewis and John Vassall met one late summer day in Red Square. It was 1974, and there were hardly any students, let alone Black students, on campus. When the two men spotted each other, they made straight for one another to introduce themselves.

They quickly discovered a few things in common: Both had gone to college in the Midwest, and both were just about to start training at the UW School of Medicine. “We shook hands, and that sealed the deal,” says Vassall. “We’ve been best friends ever since.” Soon they were sharing an apartment and, as two of just six African Americans in their medical school class, they helped one another through the rigorous training.

After completing their residencies, Vassall, ’74, ’78, and Lewis, ’78, ’80, ’83, opened a primary care practice in South Seattle. They set it up in a storefront in a neighborhood that was nearly 75% African American and had been historically underserved by Seattle’s medical community. “We walked up and down Rainier Avenue and found an old record shop,” says Vassall. The site featured a towing yard across the street and a hair salon next door. A carpenter friend installed sinks and built their exam rooms, and the two doctors opened for business.

Later, they would join a larger practice, move closer to downtown and ultimately become leaders in Washington’s medical community. Today, Vassall is an associate dean of clinical education at Washington State University’s college of medicine. And Lewis has retired after holding several executive roles at Swedish Medical Center and serving as chief medical officer for International Community Health Services.

Their careers as doctors, teachers, administrators and leaders over the past 45 years have afforded them a broad view of Seattle’s health care community. They’ve seen how the contributions of Black physicians helped make Seattle one of the most advanced medical communities in the country, and they’ve seen how, over decades, Black physicians served people from all cultures, backgrounds and levels of economic need. “Our advocacy at the local, regional and national levels, and the changes we’ve advocated for in patient safety have measurably improved outcomes for all patients,” says Vassall. He added that in their roles as chief medical officers, researchers and regional and national health care leaders, Seattle’s Black doctors have benefited everyone.

UW Medicine and its medical school—like many schools around the country—face both long-standing and fresh challenges around creating and supporting more Black doctors.

Still, more than four decades later, they see the same low numbers of Black medical students and continued disparities in health care for the Seattle area’s Black residents. Racial and ethnic diversity among doctors and other health care professionals, studies show, improves access and quality of care for underserved populations and saves lives. And today’s lack of doctors with the cultural competency to understand the experiences, challenges and medical needs of Black patients is a national concern.

While medical school enrollment of Black women has improved slightly, fewer Black men are going to medical school today than 45 years ago. According to a 2021 study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the percentage of Black male medical students has declined from 3.1% in 1978 to 2.9% in 2019. When Vassall and Lewis completed their medical degrees, they were among six Black students in their class of 125. Today, there are six in a class of 270.

Diversity in the physician workforce is crucial, says Paula Houston, ’94, chief equity officer and vice president for medical affairs at UW Medicine. For Black patients and other patients of color, having access to doctors who share their backgrounds can improve understanding and create a stronger sense of trust, resulting in better health outcomes. And training doctors alongside peers of different racial and ethnic backgrounds helps minimize health disparities.

Many pieces to this story center on health care equity, Vassall says, but one of the key points is the experience and history of Seattle’s Black doctors: Although they encountered barriers, they have been pillars of the community, they studied and taught at the UW, and “they helped us join together as a group,” he says.

In spite of this, there’s a shrinking percentage of Black doctors nationally and locally, he says. “There are fewer now, and many have gone to work for large health care companies where it’s hard [for people who want Black doctors] to find them,” Vassall adds. UW Medicine and its medical school—like many schools around the country—face both long-standing and fresh challenges around creating and supporting more Black doctors and, in the long term, expanding the number and diversity of doctors who can care for all of us.

* * *

In 1950, the UW School of Medicine graduated its first class of physicians. Two years later, Lloyd C. Elam enrolled, becoming the school’s first Black medical student. Elam, who grew up in Arkansas and attended college in Chicago, was drawn to the UW by the idea that a new medical school would be well-funded and feature the latest equipment.

His degree put Elam, ’57, on a career path to Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school in Tennessee. His successes included establishing Meharry’s department of psychiatry and serving as the college president from 1968 to 1981.

After Elam, the UW saw very few Black medical students until 1968, the year Meredith Mathews enrolled. As a UW undergraduate, Mathews prepared for medical school by focusing on hard science. “It was not a friendly place,” he says. Lost in the large classrooms, he struggled to connect with his teachers and classmates. He describes a time when he sat down at a table in Suzzallo Library and all the white students got up and left. By the time he was in 400-level courses, though, Mathews was more at home.

He and many of his fellow zoology majors had set their sights on medical school. But unlike the white students, Mathews didn’t even consider the UW. If you were Black, “the adviser had a history of deterring you from applying,” he says.

He was deliberating over acceptances from several schools when August Swanson, a UW Medicine professor, called and asked why he didn’t apply. “I let him know I didn’t think it was worth trying,” Mathews says. Swanson persuaded him to reconsider and later sought his help finding other potential students who might have been similarly discouraged.

Mathews’ medical school class had just two other African Americans at a time when many elite schools were going out of their way to draw students of color. “There was a lot of work to do” to recruit future Black doctors to the UW, Mathews says. “There were stellar students here in Seattle, and they went somewhere else,” he says, pointing to what he saw as a long-term problem with the admissions process. Where other schools seemed to say, “We’re lucky to have you,” he says, at the UW it was more like, “You’re lucky to be here.”

Mathews went on to specialize in nephrology and worked as an internist for 18 years at Pacific Medical Center. He was also a clinical associate professor at the UW. His professional journey later took him to California, where he capped his medical career as senior vice president and chief medical officer for Blue Shield of California, a $10 billion health plan with 3 million members. Today, though retired, he’s still a voice in Seattle medicine as a member of the Harborview Medical Center Board of Trustees.

* * *

Over the decades, the work of the city’s medical Black community entwined with the UW’s efforts toward teaching, research and providing care. The list of Black doctors in the region is small, but it is filled with talented and dedicated practitioners. You can find their names on lectures, scholarships and local landmarks.

One of the first, Walter Scott Brown, came to Seattle in 1931 for a surgical residency at Providence Hospital and stayed to establish a practice on Beacon Hill. He later invited William Lacey to move from Chicago and join his practice. Both served as clinical associate professors at the UW. When Robert Joyner moved to Seattle and started his practice in 1949, he brought the number of Black physicians in the city at the time to four.

Those doctors led the way for physicians like Anita Connell, who completed medical school at the UW in 1975, and opened her OB-GYN practice in 1982. In addition to serving thousands of patients, she has long been an advocate for women’s health and education. Her advocacy started early: As a UW undergraduate, she helped found the Black Student Union.

And while a small city park bears her name and her portrait hangs in the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic, Blanche Sellers Lavizzo, ’75, deserves greater recognition. She made history as the first African American woman pediatrician in Washington. Her husband, Philip Lavizzo, was one of the first African American doctors to practice surgery in the Northwest.

Dr. Blanche and Dr. Phillip, as the community knew them, set up their joint practice in Seattle in 1956. “They were part of the Great Migration,” says their daughter, Dr. Risa Lavizzo-Mourey. Black doctors from the South moved to the North and West because they “wanted to be able to practice in a less restricted way and at the same time serve their community and others,” she says. “And they wanted to raise their kids in an environment that didn’t have the cruelty and limitations of Jim Crow.”

Though Black doctors were not welcomed in the predominant medical societies, many of them found ways to have influence by leading service organizations, owning businesses, teaching and being advocates and activists.

That’s not to say they didn’t encounter racism. Most of the city’s hospitals—except for Providence—wouldn’t grant admitting privileges to Black physicians. Group Health didn’t recognize Blanche Lavizzo, though many of her patients had health coverage from the organization.

As a teen, Lavizzo-Mourey helped her parents prepare their billing statements. Before she could stuff one into an envelope, they would carefully review it and decide whether or not to send the bill or reduce the fee. This happened a lot in the 1960s during the Seattle recession. “My father said if you send a big bill to someone out of work who can’t pay, they aren’t going to come back to see you,” she says. “And he wanted them to come back, because they needed medical care.”

In 1970, Blanche Lavizzo became the founding medical director for the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic in the Central District. A satellite of Seattle Children’s, the clinic was built to provide medical and dental treatment to children from families with low income, many of them people of color. Lavizzo wove respect into the clinic’s motto: Quality care with dignity. In 1975, she completed her master’s in public health at the UW, deepening her skills for tending her patients’ overall well-being. Thousands of children saw Dr. Blanche, who led the clinic until her death in 1984.

While caring for their patients was their core endeavor, Seattle’s Black doctors often took on more, says Dr. Bessie Young, ’87, ’01, vice dean for equity, diversity and inclusion for UW Medicine’s Office of Health Care Equity. An expert in kidney disease whose research includes health disparities, Young is another UW alum (medical school, residency, fellowship, Master of Public Health) with a long view on the city’s medical community. Though Black doctors were not welcomed in the predominant medical societies, many of them found ways to have influence by leading service organizations, owning businesses, teaching and being advocates and activists, she says.

But few could keep up with Alvin J. Thompson, who moved to Seattle in 1953 and quicky became one of the most active and influential members of the city’s medical community. He established the gastrointestinal lab at Providence Hospital and volunteered at organizations including the Pacific Northwest Kidney Center, Goodwill, The Seattle Foundation, Blacks in Science and the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. He was also a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a consultant to the National Institutes of Health and a master in the American College of Physicians. And he found time to be a clinical teaching professor at the UW, where he threw his energies into students and young faculty.

With Millie Russell, ’80, ’88, who directed a UW program for underrepresented students in the health sciences, Thompson formed the Washington State Association of Black Professionals in Health Care. They brought together nurses, doctors, dentists, social workers and other health care workers to advocate for medical priorities for the Black community and improve care, research and training. “Dr. Thompson’s goal, really, was to increase admission to the medical school for Black students,” says Young. To help them with expenses, he set up an Alvin Thompson Medical Student Support Fund. He sold the family boat to add money to it.

George Counts—one of the beneficiaries of Thompson’s attention—came to the UW in 1965 on a fellowship in infectious disease. “I was ecstatic because it was one of the best programs in the country,” he says. Ten years later, he was invited back to lead the infectious diseases unit at Harborview. “I had some misgivings,” says Counts. “I had seen what academic life was like in Seattle.”

Not long after joining the faculty, Counts received a call from Thompson. “I didn’t know him before I came here,” he says. “But he took me under his wing to make sure that I did whatever was necessary to succeed in this cutthroat world of academic medicine.” Thompson pushed him to steer clear of outside projects and only focus on his research and publishing. “He was important to me, and stayed close throughout that 10-year period,” says Counts, who became the first Black full professor in the School of Medicine. “It took another 30 years [for the UW to promote the next Black full professor],” says Counts. “That was Dr. Bessie Young in 2015.”

In the late 1980s, as AIDS was spreading across the country, Counts joined the National Institutes of Health to lead the office overseeing the National AIDS Clinical Trials Program. There, he saw how women and people who weren’t white were under-recruited into research studies. He established an office within the NIH to address these and other disparities.

* * *

But not all members of the medical community in Seattle trained in health care. In 1968, the Black Panther Party started a clinic. The Seattle BPP chapter was cofounded by Aaron Dixon, a UW student, and his younger brother, Elmer. In addition to protesting racism and police brutality, they addressed basic needs and conditions of African Americans.

One fact that stood out to them was the high rate of infant mortality in the Central District. The Black Panthers found an ally in UW neurology doctor John Green. “I would call him a doctor-hippy,” says Elmer Dixon, who first met Green at a civil rights demonstration. One night, the brothers went to Green’s house to talk about opening a well-baby clinic. “He told us to get a van and go to the UW Hospital loading bay,” says Dixon. “When we rang the bell, the door opened and there he was with all the equipment we needed.” Over time, the clinic expanded to become today’s Carolyn Downs Family Medical Center.

Black doctors and leaders have shaped the city’s health care over the decades, say Vassall and Lewis. But despite all their efforts and outreach, a shortage of Black doctors persists. They point to medical school admissions, which historically focused on candidates’ personal achievements and test scores—to the benefit of those from privileged backgrounds—rather than on who in the community needed care. Many applicants can succeed in medical school, says Vassall. The issue is deciding who gets in. “We need to be thinking about who is best going to serve the state of Washington. Medical schools should be prioritizing students from rural and tribal communities and from underserved communities in Tacoma and Seattle where there is the greatest need and where they’re likely to go back and work,” he says.

While it’s not the source of the problem, Washington’s Initiative 200—which was passed by voters in 1998—bars the UW from considering race or gender in the admissions process. “It doesn’t allow us to very intentionally focus on having incentives to bring Black medical students here,” says Houston.

Funding is another challenge, Houston adds. The UW finds it hard to compete with schools that offer full rides to medical students from underrepresented backgrounds.

“It’s an ongoing battle,” Young says. “We do recruit students from the area as well as all over the country, but we need to do more to recruit and retain our students as well as trainees (residents and fellows) and faculty who are role models and help to build a welcoming medical community for our students.”

UW Medicine has more than 120 residency and fellowship programs and more than 1,550 residents and fellows, which makes it the sixth largest graduate medical education program in the country. GME is a crucial pathway for bringing more Black doctors and underrepresented minorities into the region, says Dr. Byron Joyner, vice dean for GME, a role he has held since 2014.

Joyner also has a national role representing the UW at the Accreditation Council for Graduate and Medical Education. He is one of three Black men heading GME in a group of more than 1,200 institutions. In the last seven years, he has been involved in developing policies and regulations that require residency programs around the country to recruit underrepresented minorities, and to have strategies to do so.

Fourteen years ago, Joyner was responsible for creating the UW Network of Underrepresented Residents and Fellows. In addition to supporting one another and promoting cultural diversity, NURF members provide community outreach, mentorship, recruitment and retention. They have a huge impact when they visit Seattle area high schools to build interest in medicine as a career option for underrepresented youth. NURF members also attend national conferences for Black medical students and doctors and recruit for the UW. “Our fellows and residents are among our most valuable recruiting tools,” Joyner says.

In his 23 years at the UW, Joyner has watched the institution change from having few diverse trainees to understanding that diversity, equity and inclusion should be in every aspect of teaching and care. In addition to requiring training for faculty and staff around discrimination and sexual harassment, UW Medicine’s leaders are thinking about how to mitigate discrimination, improve recruiting and better fulfill the mission “to improve the health of the public.” “It’s going to take some time,” Joyner says. “But we’re making strides in the right direction.”

Ben Danielson, ’92, a clinical pediatrics professor at UW Medicine, is a leading voice for health care equity. He directed the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic from 1999 to 2020. In 2017, he won the Simms/Mann Institute Whole Child Award for making a significant impact on the lives of young children and their families.

As a UW medical student in the late 1980s, Danielson was wary of imposing on other people. “But I found a welcoming, kind of a subtle support system” in the medical Black community, he says. In particular, he remembers Russell and Thompson. “They were so warm,” he says. They made it feel like it was going to be OK despite the demands and intensity of medical school, and that he didn’t have to outperform his classmates and be exceptional to succeed. That kind of encouragement is “what we need to do to advance diversity in our midst,” he says. “We’re not going to make inroads into anti-racism if we can’t shed our tropes that in the past we had to embody to endure.”

Danielson also sees a need for creating a more anti-racist environment in the school. “It’s a mistake to invite people to this place and not make that a priority,” he says. Higher education and medicine are deeply steeped in micro- and macro-aggressions that affect underrepresented students and patients. The portraits of the white doctors that line UW Medicine’s hallways are like a sign that tells students of color to keep out, he says. Medical students are expected to acculturate themselves to the ways the teachers and doctors around them are acting and speaking. In some cases, they witness doctors describing and treating patients from different backgrounds with different levels of respect, says Danielson. “And there is constant pressure to fit the mold. Those things erode the sense of who you are.”

As director at Odessa Brown, Danielson loved serving patients at the clinic Blanche Lavizzo helped build. “She is an enduring spiritual hero to me,” he says. Looking at her early challenges establishing herself in Seattle’s medical community and her courage to take on the work of developing and running the clinic, she is an example of someone who wouldn’t allow barriers to hold her back, he says.

But there are differences between her time and today, he notes. The field of medicine is more and more corporate—with profit margins and market forces driving decision-making. That business culture comes at the expense of urgencies like social justice and health equity, says Danielson, “It’s working against diversity.” Public medical schools are in the crossroads of the business of medicine and their public-serving mission.

Nonetheless, Danielson can imagine a brighter future. The desire for a more equitable health care system is shared deeply by many people in many different positions inside and outside of the University, he says. “But they may feel like they are alone. People may actually talk themselves out of their own power. I’ve heard it. ‘I’m just a student. I’m just a member of the faculty. I can’t make things change.’”

“But there are more of us than we realize, and we have more power than we realize,” he says. He sees promise in the younger generation of health professionals who are now making “unapologetic demands for change.” That is different than his own experience of surviving the environment or being a lone voice, he says. “Those of us with gray hair have a lot to learn about demanding change, not just hoping for it.”

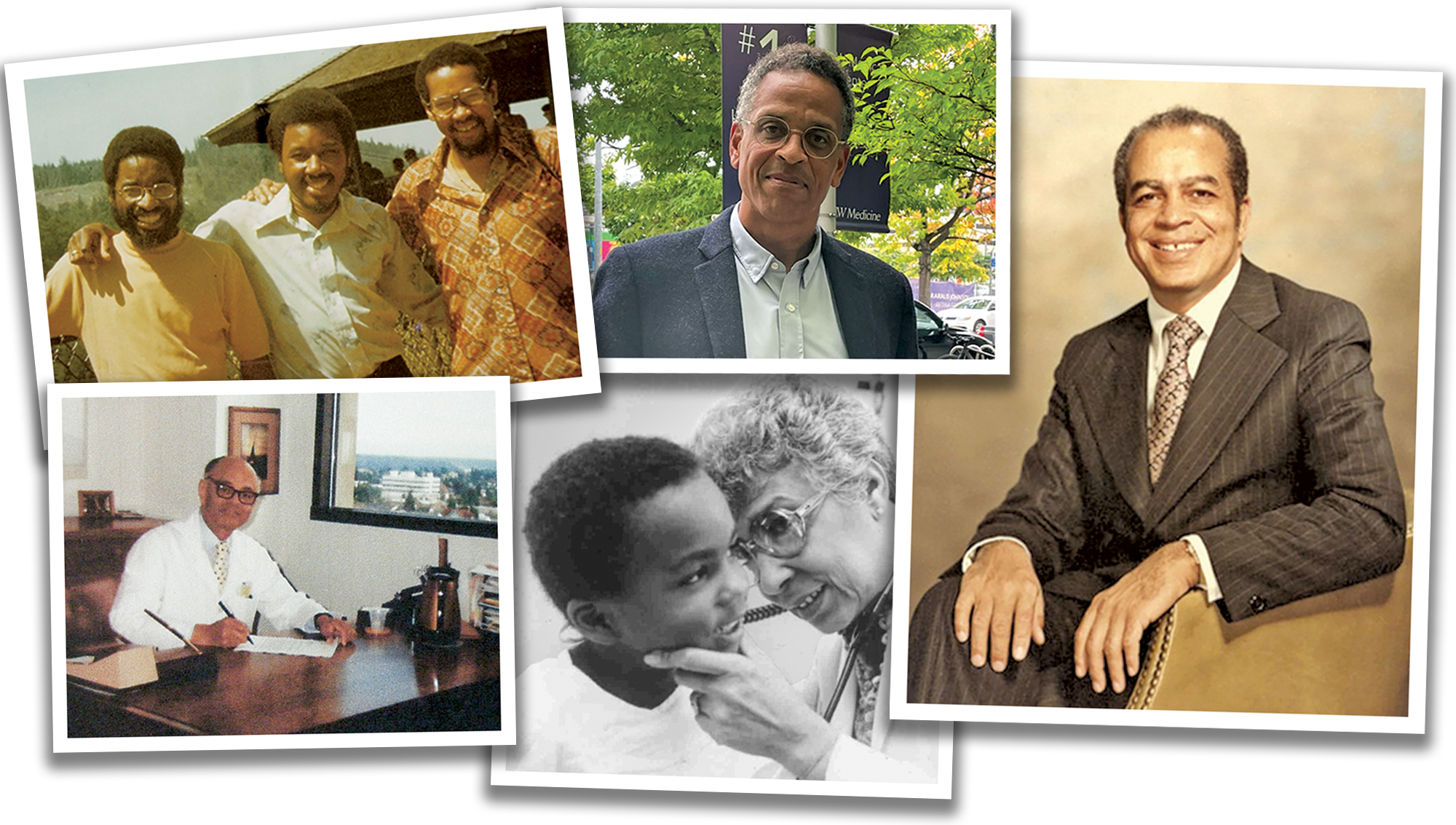

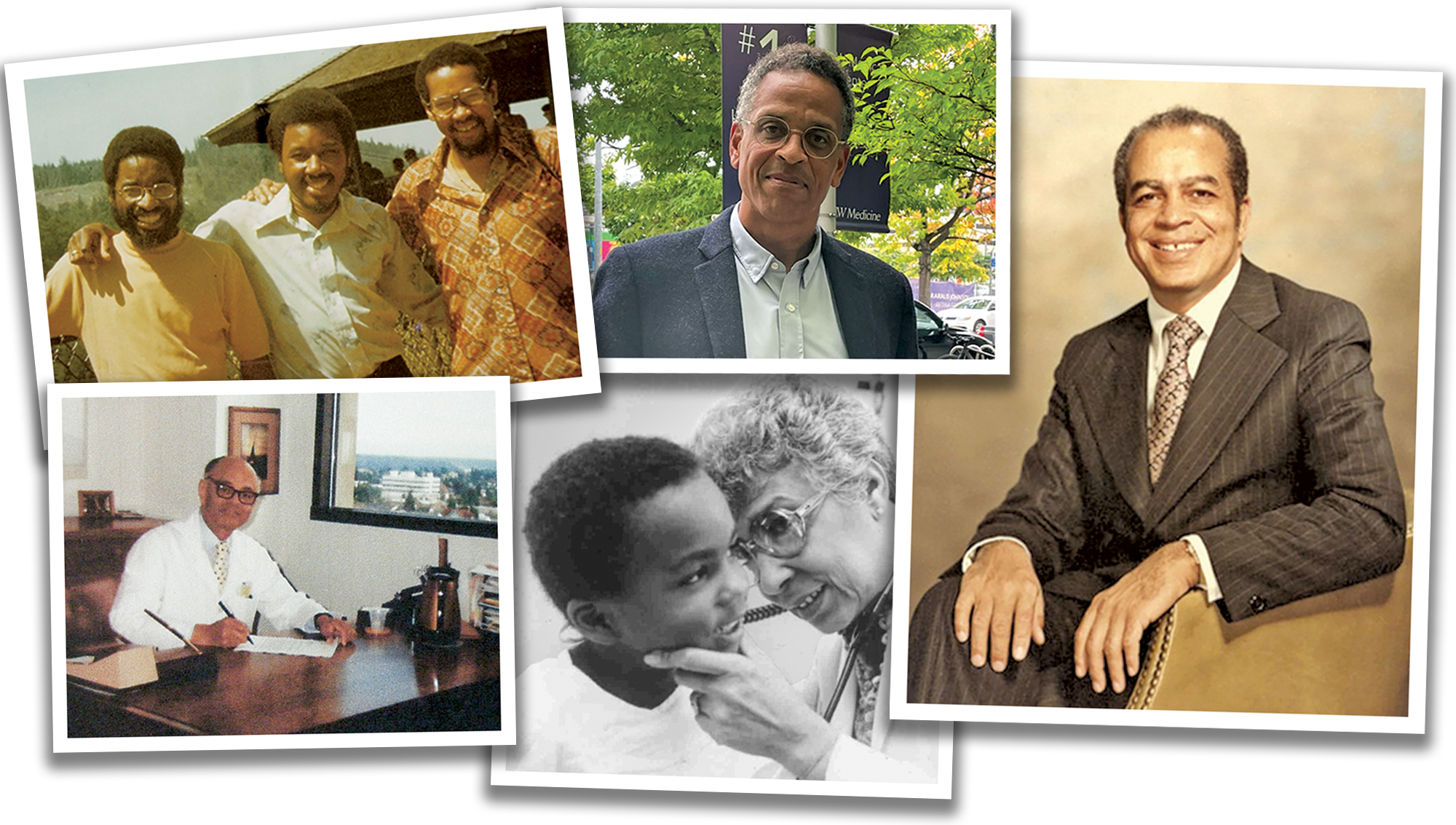

Pictured at top, clockwise from upper left: UW Medical School classmates Rayburn Lewis, John Vassall and Stephen Robinson the week they graduated in 1978; Dr. Ben Danielson, a clinical professor at the UW School of Medicine; Lloyd C. Elam, the first Black physician to train at the UW; Blanche Lavizzo, who was the first Black woman pediatrician in Washington state; and Dr. Alvin Thompson, a longtime force in Seattle’s medical community.