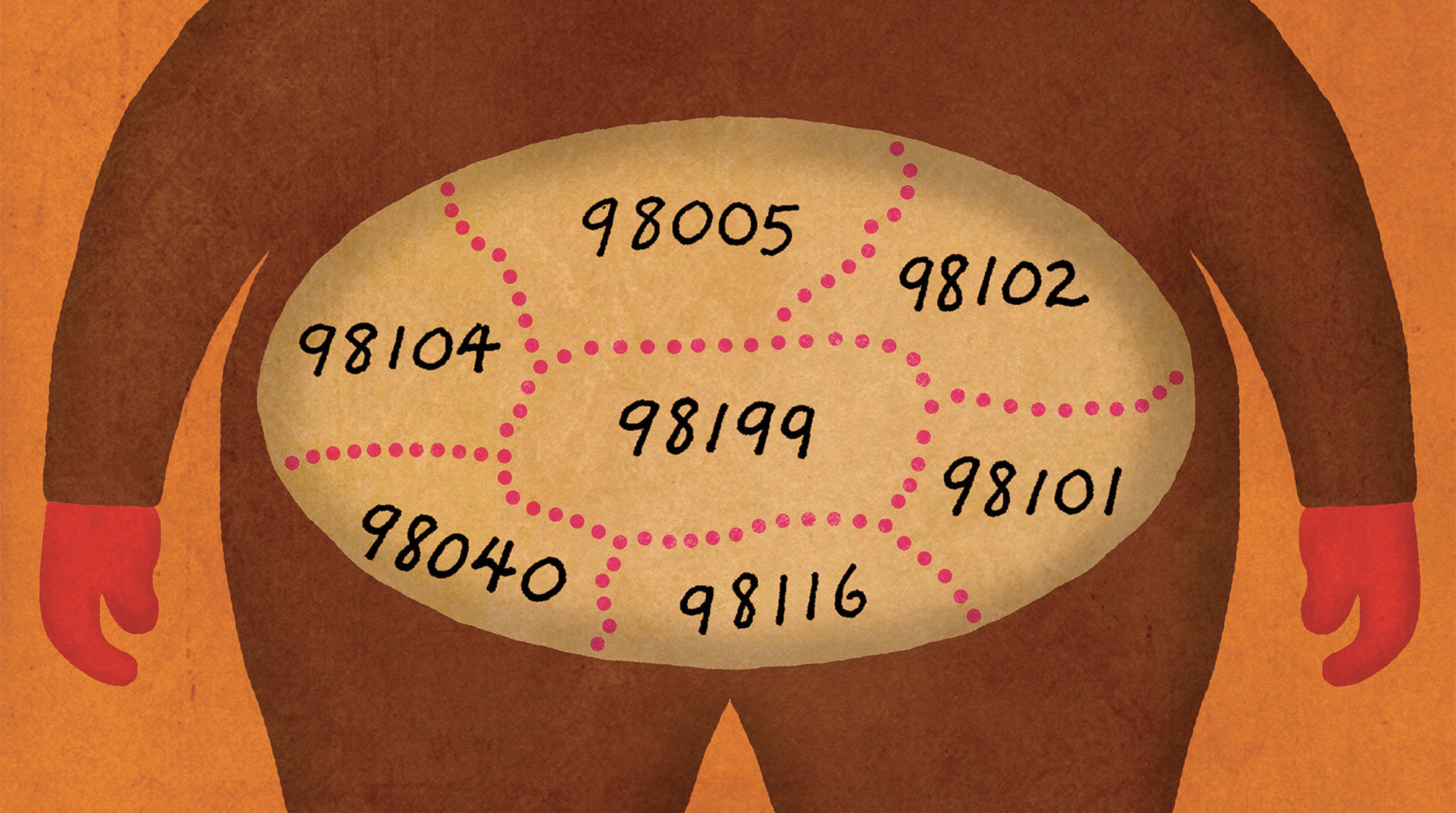

Is obesity coming to a neighborhood near you?

If your home is in King County, Adam Drewnowski can tell you. The director of the UW Center for Public Health Nutrition looks at incomes, zip codes, and proximity to grocery stores, and has found the metric with the clearest correlation with obesity and physical activity is property value. The higher the property value, the healthier an area’s residents.

The three key things that affect weight and wellness: “Location, location, location,” he says. “There really is no obesity in lakefront properties with a view.”

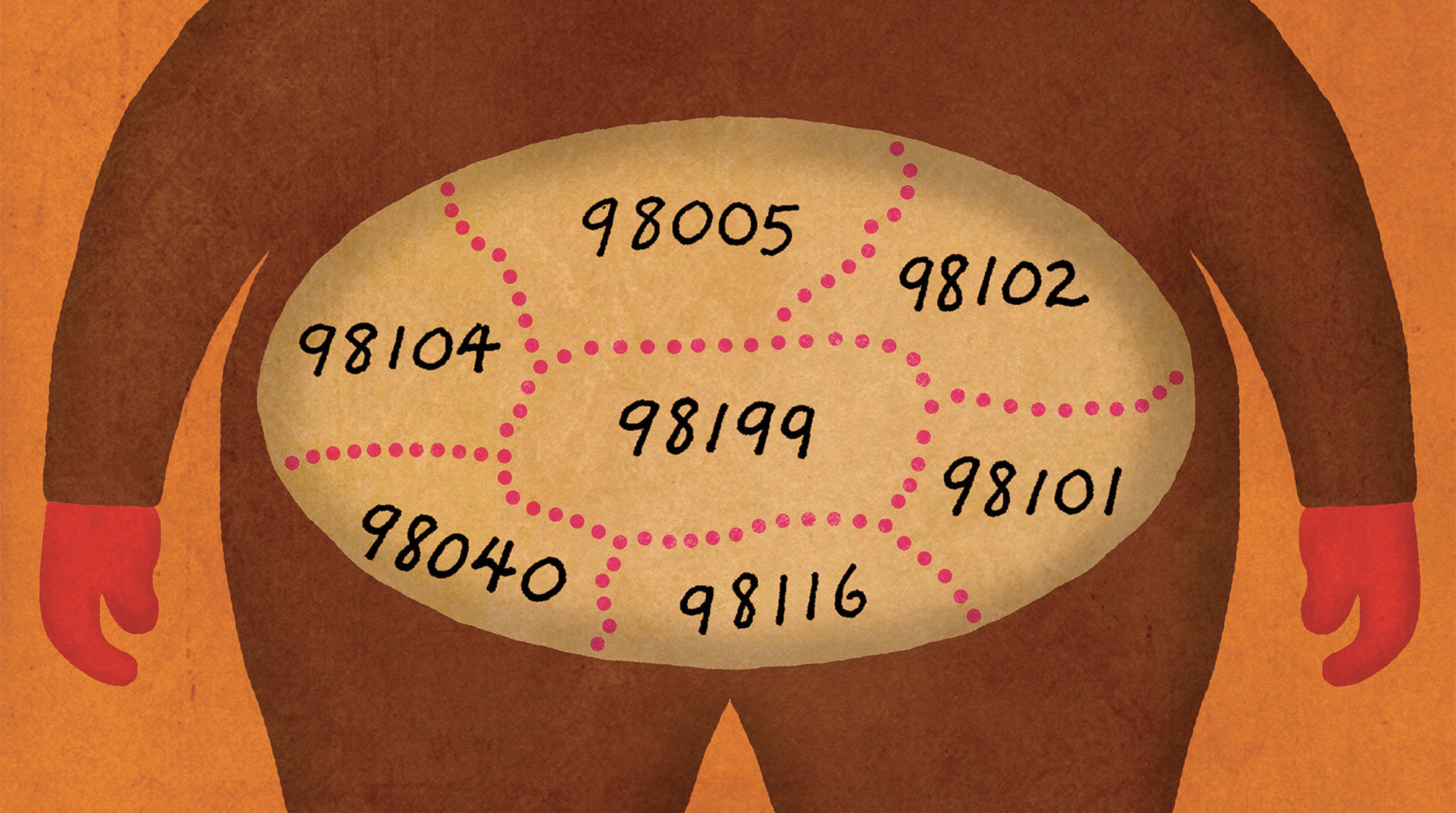

In his office in Raitt Hall, Drewnowski opens a map on his computer. “I like maps,” he says. “They pinpoint the geographic location of the problem.” This particular map is covered with colors reflecting the diet quality in King County on a block-by-block basis. Green means good and healthy, red, less so.

North Seattle tends to be more green. South Seattle and the Kent Valley, more red. “There are no groups here with very, very bad diets,” says Drewnowski. “But what you see is, we are able to map diet quality by neighborhood. This is unprecedented.”

Why is this useful? “If you have public health jurisdictions with limited resources, a map like this immediately tells you where your resources will be most critical,” he explains.

Drewnowski’s career studying obesity, social disparities in diets and health ties directly to the University’s Population Health efforts, which focus on improving human health and well-being, social and economic equity, and environmental resiliency.

“Food and nutrition and diet are at the forefront of population health,” says Drewnowski. “Most non-communicable diseases are diet-related.”

Research about diet, health and equity, usually focuses on food deserts and the distance to healthy food sources. “But we really should be talking about access to foods,” says Drewnowski.

“Access” includes cultural preference, experience cooking, time and, last but not least, money. “Obesity is very much an economic issue.”

Leading a recent NIH-funded Seattle Obesity Study, Drewnowski and his team conducted a survey of men and women in King County. Typically, studies like these look at access to markets, fast-food restaurants and convenience stores. But through his study, Drewnowski realized that rather than shop at their nearest supermarket, residents went to the one that best suited their needs.

In King County, any supermarket is just 20 minutes away, he says. “And then there are expensive supermarkets. And then there’s Whole Foods,” he says. He found that people who shopped at Safeway and QFC were more likely to be overweight than those who frequented Whole Foods and the Puget Consumers Co-op (PCC). Whole Foods shoppers bought more fresh fruit and vegetables than those who shopped at Safeway.

When incomes drop, families shift their food choices toward cheaper, energy-dense foods. Whole grains and seafood give way to pastas, cereals and fatty meats, says Drewnowski. He also found that limits of kitchen facilities, cooking skills, and time contribute to people pursuing tasty, but nutrient-poor, calorie-rich foods.

How do you counter that? “Minimum wage is a very effective way of providing a safety net,” he says. With more income, families can afford healthier foods like fruits and vegetables and have the time to shop for and prepare them. And there, he notes, the issue slides out of the nutrition realm and into public policy.

Nutritionists can’t look at food and diet in isolation, says Drewnowski. His colleagues in urban development have found that most farmers markets are in northern King County while a greater number of fast food restaurants operate in the south.

“Was it fast foods making the community obese, or fast foods locating near the obese?” he asks. “Our work on geography points to unequal distribution of food resources. That is why we (created this) map.” But how do we fix this situation? By improving the quality of foods in grocery stores and promoting urban gardens, he says.

Many elements surround food and human health, not the least of which are social justice, cultural practices and environmental impact. David Battisti, the Tamaki Endowed Chair in Atmospheric Sciences, for example, studies how climate change will affect food production. It’s all part of the bigger picture, says Drewnowski: “Our dietary choices affect the environment and impact climate change. And climate change will affect what we will eat in the future.”

Cultural Anthropology Professor Ann Anagnost teaches students about the cultural politics of diet and nutrition, exploring things like whether current federal dietary guidelines are optimal for health. UW Bothell global studies lecturer Kristy Leissle studies the chocolate trade and the inequities of race and gender that it perpetuates.

Nutritionist Jennifer Otten from the School of Public Health is working with the Evans School of Public Affairs & Governance on a five-year study of the impact of raising minimum wage. One key question: Does raising the minimum improve quality-of-life measures, including health, nutrition and daily family life?

Brandon Born, associate professor in urban design and planning, examines food systems in urban environments. Only recently has food been integrated into land use and city planning, he says, which is why he devotes time to connecting the University’s studies and experts to public policy makers.

“Traditionally,” Drewnowski explains, “nutrition has been concerned with biology and metabolism of things like Vitamin A. But the new nutrition absolutely embraces the economic environment, anthropology, geography, ethnography, environmental science, what people eat and why and for how much. All these components are part of what we do.”