Digital dynamo Digital dynamo Digital dynamo

UW Libraries has undertaken a massive effort to expand access to digital resources and teach the skills to use them.

By Sheila Farr | March 2021

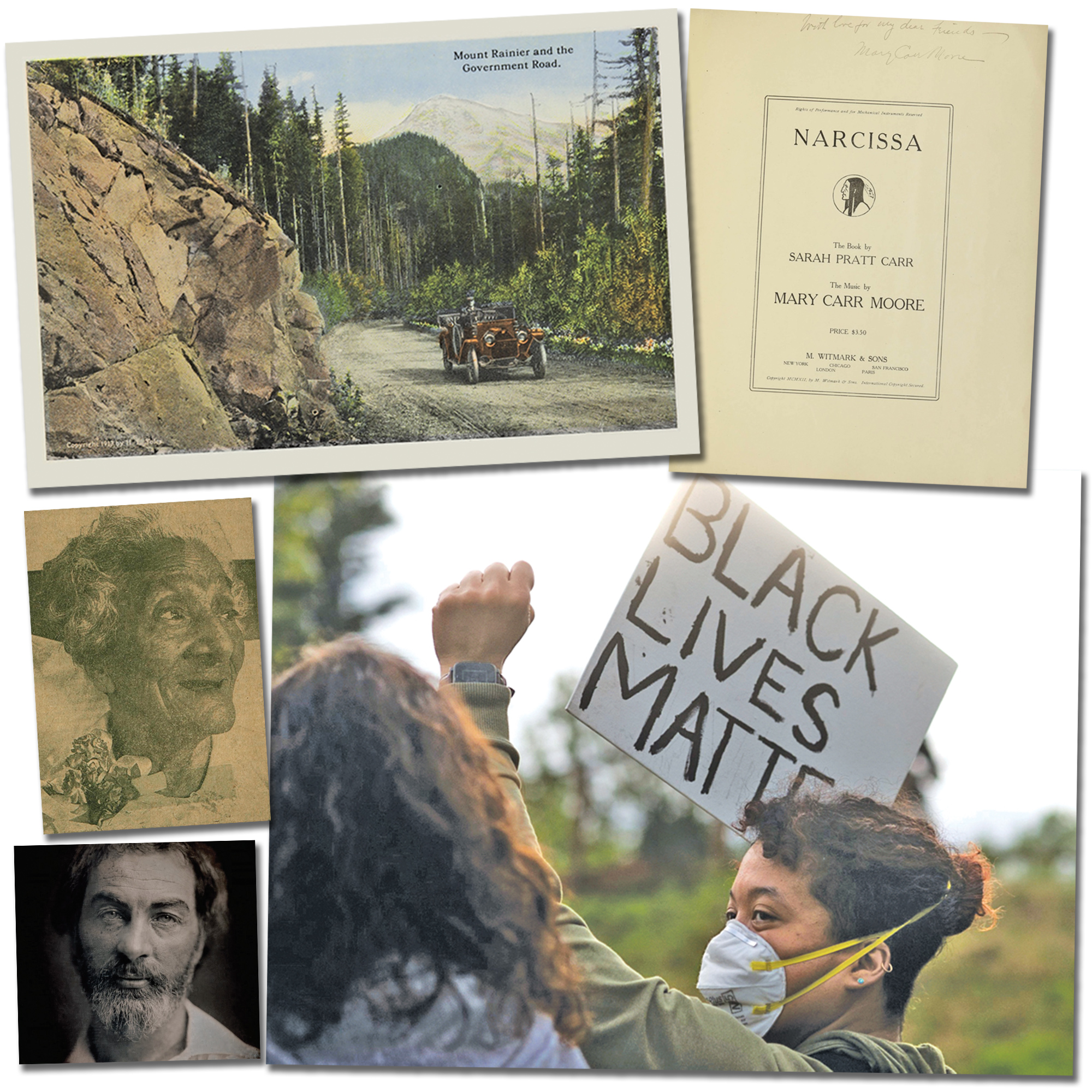

On April 22, 1912, an extraordinary opera premiered at Seattle’s Moore Theatre, with imported New York stars and a 65-member chorus. Billed as “the first grand opera ever written by an American woman,” “Narcissa” was composed by Seattle resident Mary Carr Moore and glorified the life of Washington pioneer Narcissa Whitman—one of the first two white women to cross the Rocky Mountains. Narcissa and her husband, Marcus, were killed in an 1847 Indian raid at the Walla Walla mission they founded on tribal lands. (Initially, they were declared innocent victims of a massacre. Historians have since re-evaluated that assessment.)

Now, more than 100 years later, a piano and voice score of “Narcissa,” signed by the composer, is part of a trove of rare music in the UW Library system that was recently conserved and digitized. Resewn and placed in a fresh binding, the score was photographed and made available online for the use of scholars here and around the world.

In recent years, the digitization of library materials has been a priority at the UW and other libraries around the world. But last year, the COVID-19 pandemic and the moving of instruction to remote learning pushed that process into overdrive. To make remote learning feasible, the role of libraries has expanded exponentially. And librarians have become essential teaching partners, helping faculty incorporate new software tools so students can keep their coursework on track from home.

“Moving to online teaching at warp speed was a huge challenge,” says Beth Kalikoff, director of the UW Seattle Center for Teaching and Learning. Fortunately, Kalikoff points out, UW Libraries was already leading the way in digital initiatives, even before the pandemic.

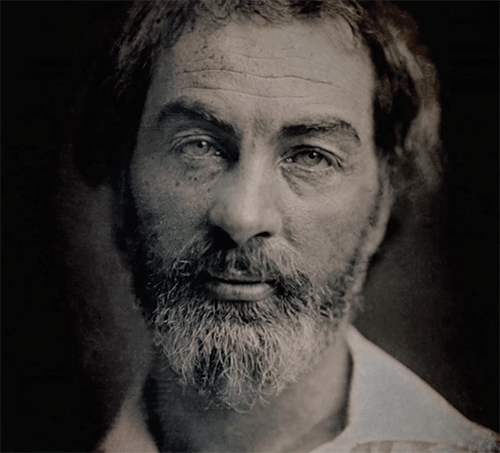

Last year, to facilitate remote learning, UW Libraries invested more than $220,000 to purchase more than 250,000 new e-resources—including funding from endowments and $80,000 from donors to the Libraries’ COVID Relief Fund. Among the new subscription services is Academic Video Online (AVON), the most comprehensive video subscription available to libraries. Offerings include current affairs documentaries such as “John Lewis: Good Trouble” and the “Frontline” episode “Policing the Police” as well as the “Poetry in America” series, cinema classics and film criticism. Comprising some 70,000 titles, AVON offers thousands of videos in American history, business and economics, arts and architecture, nursing and many others. The libraries have added individual science e-books and business case studies, as well.

A piano and voice score of the 1912 opera “Narcissa,” the “first grand opera ever written by an American woman,” is part of a vast collection of rare music that the UW Library system conserved and digitized.

Students in the performing arts have been especially hit hard by the shutdown. In response, arts librarians Madison Sullivan and Erin Conor worked quickly to expand access to online resources. The purchase of an enhanced subscription to the Classical Scores Library now brings musicians access to most major classical scores in a printable format, as well as harder-to-find contemporary works. Improved access to the Drama Online Core Collection made scripts to 1,700 new plays available, on top of existing classics. Particularly relevant right now is the New Play Exchange, which adds diversity to the playlist. Comprising work by living playwrights whose scripts may not have been easy to locate before, the database is searchable by racial, ethnic and gender identity, as well as by title and author. And as always, the department depends on its popular subscription to Shakespeare’s Globe on Screen, with videotaped performances from the Bard’s Globe Theatre in London.

Dance students have seen their studio practice upended by the pandemic. For them, access to streaming video has been more urgent than ever. Dance Online: Dance in Video offers documentaries and full performances by top 20th century performance groups and individuals, including the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Mark Morris, Donald McKayle, the American Ballet Theatre and the Dance Theatre of Harlem. For more cutting-edge recent works, students can turn to Seattle’s ontheboards.tv, which offers high-quality videos of full-length shows in dance, theater, music and multimedia performance.

But online learning means more than watching: impact and active participation are essential. To support faculty and students in creating and sharing their research openly, the libraries created the Open Scholarship Commons (OSC). The OSC is a one-stop hub for consultation, workshops, and events that connects the UW community across disciplines. This is the place where students and faculty can access a range of tools and guidance to create open digital books and exhibits, as well as hone new research skills in areas such as text mining or data visualization. They can learn new and more equitable ways to publish, and get assistance with the complexities of fair use, copyright and data management—major stumbling blocks for many in the digital era. For now, the OSC exists online only, but when campus reopens there will be a welcoming physical space in Suzzallo Library as well.

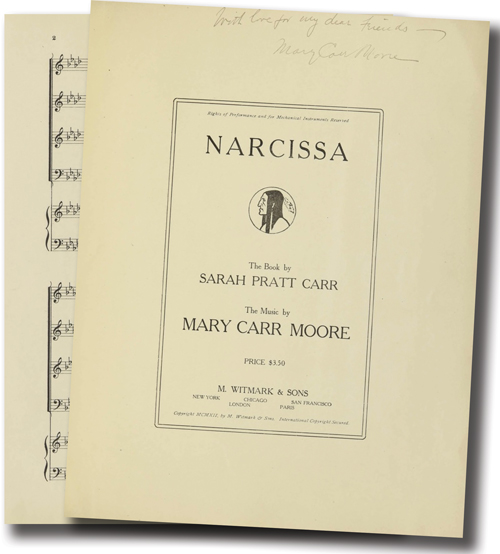

These scenes from the 1913 color postcard Book, “Souvenir of Rainier National Park, Washington,” are part of a particularly important primary resource for remote scholarship called HathiTrust, a collective repository of digital content from research libraries in the U.S., Canada and Europe.

Betsy Wilson, vice provost for digital initiatives and dean of university libraries, has led the libraries system for the past 20 years, a period of unprecedented change. With a staff of 350 in libraries serving three campuses, she has overseen a massive shift from print to digital formats. And as the core function of libraries shifted, she notes that the role of librarians evolved as well.

“Librarians and libraries staff are much more than a conduit to finding materials,” Wilson says. “In a typical year, our staff teach more than 800 instructional sessions. We work with faculty to design courses, teach research methodology and advise students on writing, research and all forms of digital scholarship, including data use and management, publishing and copyright.”

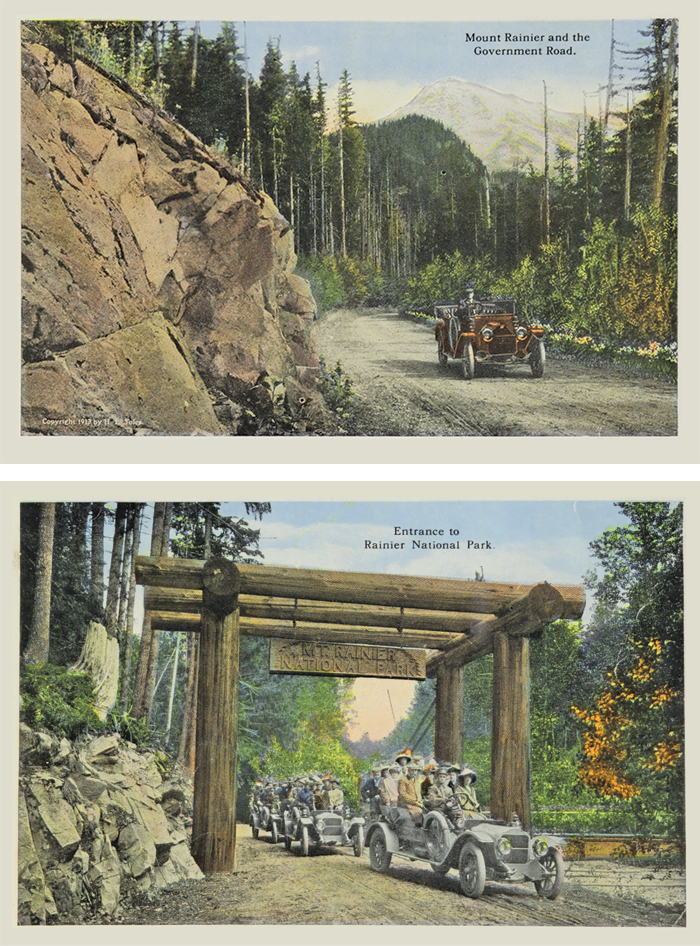

Last year, for example, data and digital scholarship librarian Erika Bailey teamed up with two UW Tacoma classes—led by Sonia De La Cruz, assistant professor of communication, and sociology professor Tanya Velasquez, who worked in collaboration on the 2020 Black Lives Matter Storytelling project. Students participated in group discussions and produced written stories, videos and other forms of creative work to explore their experiences related to the Black Lives Matter movement, race, racism and racial justice. With guidance from Bailey and content manager Adam Nolan, the students contributed their materials to a kaleidoscopic e-book using the program Pressbooks to mesh written content and video in a multimedia format that could then be publicly shared.

Part of Bailey’s task was working with faculty to instruct students on privacy considerations, including consent for use of work, understanding what it means to put students’ names and images on public media, helping students understand copyright issues and concerns. “Without Erika’s support, we would not have been able to translate this work into a digital publication,” De La Cruz says. “The students truly enjoy knowing that their work has the possibility of being shared and seen by others.”

The highly successful 2020 Black Lives Matter Storytelling Project engaged students in timely, difficult conversations about race, racism and racial justice, thanks to the work of data and digital scholarship librarian Erika Bailey and professors Sonia De La Cruz and Tanya Grace Velasquez.

One primary resource that’s been especially important for remote scholarship is HathiTrust, a collective repository of digital content from dozens of research libraries in the US, Canada and Europe. HathiTrust comprises a digital library, a research center, a shared network of print collections, and a portal to US federal documents and publications. HathiTrust also has a copyright review team to locate and open materials in the public domain. It’s the site where faculty and students can find the score of “Narcissa,” and other rare music from the UW collection. Or they can access “A History of Snohomish County, Washington,” published in 1926 by Pioneer Historical Publishing Company. Or browse the 1913 color postcard book, “Souvenir of Rainier National Park, Washington,” with photographs by Asahel Curtis (1874-1941).

HathiTrust gives UW faculty and students access to a vast trove of information while enabling scholars around the world to dip into the UW’s rich archive. Due to copyright restrictions, not all materials in the database are universally available. However, during the move to remote learning, HathiTrust Emergency Temporary Access Service has allowed special access by current UW faculty, students and staff to more than 1.7 million electronic volumes of the UW Libraries print collection and items in the public domain (out of copyright). (Access does not extend to members of the UW Alumni Association, Friends of the UW Libraries or members of the public who purchase a UW library card.)

Dr. Nettie Asberry was an early African American resident of Tacoma known for her work in fighting racism and in opening doors for women. She is believed to be the first African American woman in the US to receive a doctorate degree. Her story and more like it are available online thanks to the HathiTrust, a collective repository of digital content from research libraries from the U.S., Canada and Europe.

Helping faculty and students understand the complexities of copyright in the digital age is a big part of the transition to online learning, says Denise Pan, associate dean of university libraries for collections and content. With a book, she says, the library can simply buy a copy and check it out to whomever needs it. With digital licensing, the library must pay for different levels of access: for single or multiple users, for a restricted timeframe or perhaps a limited geographical use. That means a book could be available to students here in Washington, but international students might not be able to tap into it if they are abroad. To offer more equitable access for all students, Pan says, UW Libraries is encouraging instructors to work with librarians to find available online alternatives to some textbooks, sources that are already open, licensed to UW or both. As demand grows for subscription services and digital textbooks, prices do, too. With current and predicted budget shortfalls due to COVID, the library is reviewing existing databases, journals and subscriptions for potential cuts.

Yet even as digital needs increase, some parts of the library system still depend on good old fashioned print. That’s especially true of the library’s International Studies Units, where shipments of books and journals from East Central and Southeastern Europe, Russia and former Soviet republics, the Near East, South Asia and Southeast Asia continue to arrive regularly. Michael Biggins, the Slavic, Baltic and East European studies librarian, says that in some of those regions, access “to currently published, born-digital books and periodicals still ranges from highly restricted to nonexistent.”

Each year, Biggins says, his unit orders and processes up to 15,000 newly published books, many more periodicals and journals, as well as sound recordings, musical scores and other papers. But with the libraries closed, boxes and parcels began to pile up. As soon as it became possible, a few multilingual staffers in the department, using safety protocols, began going to campus once every other week to sort the shipments from around the world and deliver them to workers at home. The material—published in dozens of different languages and scripts—must be matched to the orders, entered into the UW online system, and linked with metadata so that it can be easily located and accessed. After the materials are processed, members of the team drive from house to house, recover the boxes and deliver them back to the library into queues for proper routing and shelving.

Also, as the governor’s restrictions allowed, some staff resumed work behind the scenes at library facilities to initiate curbside pickup for books and interlibrary loan materials that are not digitally accessible. They too faced a huge backlog of mail and invoices, accumulated boxes of acquisitions, and, of course, the task of locating, pulling and checking out current materials for pickup.

The “Poetry in America” series, featuring the works of Walt Whitman, is among the 250,000 new e-resources offered by the UW Libraries, thanks to a $220,000 investment that included funding from endowments and $80,000 from donors to the Libraries’ COVID Relief Fund.

But if anything has been made clear during this pandemic year, it’s this: Checking out books is no longer the main duty of libraries. “The thing that has impressed me in these weird times is how important remote access to resources is,” says Moriah Caruso, digital preservation librarian and collective collections strategy librarian. “It’s more equitable: The working moms in school don’t have to come into the library during open hours, or at all… It’s forced us to learn and grow. If there is any silver lining, we have proven we can move quickly to change our services.”

For Dean Wilson, who will be retiring at the end of the school year, making the libraries user friendly has long been a priority. Now more than ever, the library system serves as the lifeblood of the University.

“Libraries are so much more than a place to study and access materials,” Wilson says. “No matter what year of study, major or what department someone comes from—everyone uses the libraries. The ways that people use the libraries has shifted during COVID, obviously, but the role of libraries as a gateway to knowledge and support for teaching, learning and research has not.”

When the pandemic forced the University to move to remote learning, Dean of the Libraries Betsy Wilson didn’t stand still. She and her teams worked quickly to galvanize donor support and expand access to digital resources system wide, providing essential support for UW faculty and students during remote learning.