Self-help or

self-hoax?

Self-help or

self-hoax?

Self-help or

self-hoax?

Self-help books should be subject to the same rigorous testing as a new drug, a UW expert says.

By Alansa Bates | June 1990 issue

“Self-help books hardly help anyone and can even cause harm.”

“Self-help books can be as effective as private therapy.”

Both claims have been made, heatedly, by psychologists in the past year. And with up to 5,000 new self-help books now being published annually—dealing with everything from saving one’s marriage to curing insomnia—the controversy over the books seems to be reaching the boiling point.

Advocates point to research made public last year by University of Alabama Psychologist Forest Scogin. After his subjects read one of two books on relieving depression, two-thirds of them showed significant improvement. Their progress even matched rates achieved by therapists.

Self-help books are more democratic, these proponents add. They reach thousands of people who would never go to a therapist because of inaccessibility, cost or simply resistance to discussing their personal problems.

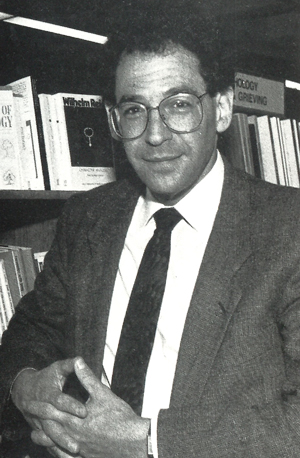

But there are plenty of dangers waiting on the bookshelf, warns one Seattle psychologist. “The typical self-help book is marketed without being tested and with exaggerated claims,” says Gerald Rosen, a UW clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

Gerald Rosen, UW clinical professor of psychology and behavioral sciences.

Rosen feels that testing is imperative. Research has shown, he says, that “well-intentioned instructions may be totally useless on a self-administered basis—even though they worked beautifully beforehand in a clinic.” This may be because a book is poorly written or has too many steps, or because the user has poor reading skills.

Rosen also questions whether people can always diagnose their own problems accurately enough to choose the best text. And even if you find an appropriate book, being your own therapist may still be tricky. It’s one thing if a person uses a self-help book to make relatively uncomplicated changes—an example might be a parent’s guide to toilet training. But Rosen has seen one publisher asking for manuscripts in a number of complex areas, “including do-it-yourself treatment for sex offenders.”

The lack of testing and the hype surrounding these books, however, is Rosen’s “biggest gripe.” He knows first-hand about these traps, since he experienced them himself more than a decade ago.

Rosen wrote two self-help books, one on overcoming fears and the other on relaxation. “I got excited and went through self-deception with the first book,” he says. “My publisher made the exaggerated claims for it, but I take responsibility for them.” There were no exaggerated claims made for the second book, he says, but it was “basically untested.”

Since then, Rosen has been a national leader trying to help others avoid the same mistakes. In 1978, he chaired an American Psychological Association task force on self-help materials and lately he has been urging the association to take steps to protect the consumer.

Richard Stuart, a UW clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, also suffered from marketing hype when he and his wife, Barbara, wrote a weight-loss book several years ago.

The Stuarts surveyed 25,000 weight-conscious women to determine why 94 percent of all women’s diets fail—and why the other 6 percent succeed. The book summarized these experiences and formulated guidelines for helping women lose weight by first dealing with the marital or family problems that, the Stuarts found, often sabotaged the diets.

Although they are pleased with the book itself, entitled Weight, Sex and Marriage: A Delicate Balance, “the publisher sensationalized it,” he says, “and that’s a mistake.” They never even saw the book’s artwork or dust jacket until after the work was published.

Stuart recalls that one publicist picked up on a relatively insignificant finding: some women become more promiscuous after losing weight. On the book tour, a TV publicist then pulled out a related, isolated incident where one woman, not identifying her “new” self with her “old” self, looked in the mirror and thought, “I don’t care who that woman sleeps with.”

Most self-help books aren’t tested after the book is written, and although the Stuarts’ book was based on hard data from their survey, it too was untested.

In contrast, UW Psychology Professor Robert Kohlenberg wrote and tested Migraine Relief, “one of the few self-help books that has been tested in a clinical trial,” the author notes.

The push towards testing, Kohlenberg says, is discouraging lots of would-be, self-help authors because the process is time-consuming and expensive. It took two years to test different versions of Migraine Relief on hundreds of people.

Through the testing, he uncovered what he calls “the number one problem with self-help books,” which is a lack of follow-through. Even though his subjects were willing and motivated, only 20 percent read his entire book and a mere 2 to 4 percent complied with all of the book’s suggestions. “We now know that people do practically none of what you say,” he laments.

Those who don’t follow all the directions—or even those who do but have an ineffective book in their hands—often put themselves in a no-win situation. If they don’t improve after trying a book, they may feel like a failure and find their problem worsens.

Self-help books can also be time-consuming dead-ends. An example, Kohlenberg says, is the trend in “affirmations”—repeating to yourself positive thoughts such as “I am a loveable person,” in an attempt to improve self-esteem. “But self-affirmations don’t help at all with self-esteem problems,” he says. “People must instead work on their relationships with other people.”

Despite all of the overwhelming drawbacks to the books, the UW authors, like most psychologists, are in favor of well-done self-help books. Rosen, the most vocal of the critics, says he’s involved in the debate on self-help books “because I’m an incredible advocate of self-help programs.”

Indeed, the idea of helping oneself autonomously seems to be a perfect fit for the independent American spirit. “Self-help books appeal to the do-it-yourself personality,” says G. Alan Marlatt, UW professor of psychology and director of the Addictive Behaviors Research Center. This year, he completed a self-help book aimed at teaching college students skills to control excessive drinking.

Marlatt’s book was tested as it was written, and he says it is clearly effective in getting readers to both reduce consumption and maintain that improvement, even two years later.

Books like Marlatt’s and Kohlenberg’s ought to be the start of a responsible trend. Rosen sees his colleagues across the country as having the skills—and the obligation—to improve self-help books. They might experiment, he says, with writing them like novels, or in short steps, or at the high school level.

Authors could also put a self-assessment procedure at the front, a chapter measuring progress at the end, and warnings throughout on not blaming yourself if the project ends in failure.

The American Psychological Association could also do much to protect the public from dangerous or useless books, Rosen feels. However, Stuart worries that the association might violate guarantees of free speech and become prey to lawsuits if it gets into the business of policing self-help books. “There are some very scummy books out there,” he says, “but getting rid of them may not be worth the price.”

Rosen counters this by noting that the association needn’t condemn “bad” books but could, for instance, endorse books that do meet certain criteria. It would be like the American Dental Association seal of approval on a tube of toothpaste. Freedom of speech is simply not an issue, he maintains. “I’m just looking for ways to make the marketplace responsible,” he says. “Claims for product effectiveness don’t fall under free speech. You can control the marketing of a product if it’s dangerous. Self-help books should be subjected to the same testing as a drug for depression.”

What to avoid in self-help books

UW Clinical Psychologist Richard Stuart is a specialist in weight loss and for 13 years was psychological director of Weight Watchers International. He says, however, that an author’s credentials are not always an indication of how useful a book will be. “Some atrocious books are written by M.D.s and Ph.D.s and some books written by those without credentials are useful.”

Stuart suggests avoiding self-help books that:

- Don’t offer data to support their conclusions;

- Don’t have bibliographies;

- Promise permanent change; and

- Purport to be the universal answer to the problem.