New York City, 1952: A hunger for modernist architecture had seized postwar Manhattan. On Park Avenue, the country’s first International-style office building neared completion. Even before Lever House’s opening, the press praised its 24 stories of blue-green glass and stainless steel as a “sea-colored jewel.” Lever House was elegant, sleek and metallic. It was the perfect symbol of a modern city.

The building’s architects announced a competition to design Lever House’s interior wall curtains. In those years, design competitions had a media following and the winners attracted a wealth of future work. With all its pre-opening hype, Lever House drew the country’s most renowned fabric designers to compete.

Jack Lenor Larsen, 2005 Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus.

The winning design was clearly the work of a visionary. Made of translucent lace and intertwined with linen cord and gold metal, the curtain had a soft, hand-woven look that perfectly contrasted with the building’s cool modernism. Yet when the architects revealed the winner’s name, it belonged to an unknown young man fresh from the backwater of the Pacific Northwest: Jack Lenor Larsen.

As Larsen’s big break, the Lever House commission jump-started a 50-year career that brought the Seattle native worldwide renown as the “dean of 20th-century textile design.” At its peak, Larsen’s company operated in more than 30 countries, employing several thousand craftspeople to weave his carpets, curtains and upholsteries. His fabrics are featured in the permanent collections of 16 world museums — including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London — and he became the second American ever to have a solo exhibition at the Louvre.

But his designs never looked as if they belonged only in museums. As the “Larsen Look” has changed each season, he has always managed to stay cutting-edge. “It’s a contemporary look of the contemporary time you’re at,” says Lotus Stack, textiles curator at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. “Maybe that’s part of the magic.”

Everyone from Frank Lloyd Wright to Marilyn Monroe has purchased his fabrics, and his creations have graced the lobbies of such architectural icons as the Sears Tower and the United Nations Building.

For his impact on the world of art and design — and for the joy and beauty his work has given to the world — the University of Washington and UW Alumni Association have named the 1949 graduate this year’s Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus — the highest honor the UW bestows upon its graduates. Larsen joins the ranks of 64 alumni who have been honored since 1938 with this award, including fellow artists and architects Dale Chihuly, Chuck Close, Imogen Cunningham, George Tsutakawa and Minoru Yamasaki.

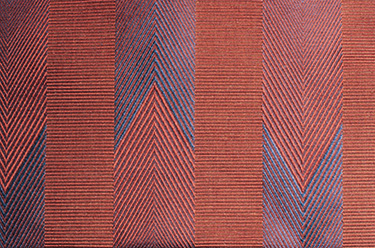

Two of Larsen’s landmark fabrics—Nimbus and Solar Cloth—are folded together. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

Born in 1927 as the only child of Canadian immigrants, Larsen was inquisitive and industrious. Growing up in Bremerton, he spent class time dreaming up expeditions along Puget Sound’s rocky beaches and through its cedar forests. From an early age, he craved his parents’ approval — especially that of his father, a building contractor who showed little interest in his son’s attempts to construct forts and watercrafts. Still, the young Larsen built incessantly: “Boats, kayaks, camps — anything I could,” he recalls.

At 18, Larsen’s affinity for building led him to the University of Washington’s architecture school. The freedom of college life instantly appealed to him, and he finished three years’ work in under two years.

Larsen’s first introduction to weaving came at the end of his sophomore year, in an interior design class. After two years of drawing boards and blueprints, Larsen relished making things again. “It was back to building and using materials and making something,” he remembers. “I stayed in the studio the extra hours I had, and decided I’d be a weaver instead of an architect.”

A man in weaving classes — then part of home economics — was a rare sight on campus. The female professors encouraged Larsen in his decision, but his father pressured him to stay in architecture. The elder Larsen wanted his son to be a success — but not in a “feminine” field like weaving, then regarded as a pastime for homemakers. So when Larsen informed his parents that he’d decided to drop out of school to be a weaver in Southern California, “I was disowned,” he recalls. “My father said it was the ‘garbage can of the nation.’ ”

His father cut off his allowance and froze any inheritance money. But Larsen held out for almost a year, enjoying California’s bohemian lifestyle. “Finally, my parents came down with a deal,” Larsen says. “If I would come home, they would buy me a big loom.”

dgar Kaufmann Jr., son of the original owner of the Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece Fallingwater, commissioned Larsen to redo the carpets, upholstery and wall hangings in his western Pennsylvania retreat. The fabric designer provided textiles for the house mostly based on his Doria patterns. Seen above is the living room. Photo by Thomas A. Heinz, courtesy Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The bribe worked. Larsen returned to the University in 1948 and became an assistant to weaving instructor Ed Rossbach — the only other male in the department. Rossbach recognized Larsen’s passion for fabric and urged his assistant to teach private weaving classes at the Seattle Art Museum. Eventually, he recommended Larsen for a scholarship to Michigan’s prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Art.

After graduating in 1949, Larsen moved “back East” to weave at Cranbrook. He finished the academy’s two-year M.A. program in nine months, producing at twice the pace of the other students. Over spring break, Larsen traveled to New York to show his portfolio to several major design studios. They all turned him down, saying his style was too individual and wouldn’t sell on the American market.

Larsen’s fabric Obelisk was a dyed linen created in 1959. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

Larsen faced a difficult choice. He had offers to teach design at Midwest colleges, but he desperately wanted to return to New York — the “first place I’d felt at home,” he says. One designer, Arundell Clarke, had shown modest interest in Larsen’s work. While Clarke couldn’t employ Larsen, he offered to put him up for a few months. So Larsen sent his looms and 39 cases of yarn to New York and started weaving. That fall, he won the Lever House contest. After that, the commissions never stopped.

In the early ’50s, New York was a promising place for an ambitious young designer. “Modern design and architecture dominated both New York’s art circles and the press,” Larsen remembers. “There hadn’t been much building in the Depression, and certainly not during the war years. But suddenly people were saving money for the first — and last — time in their lives. There was a great deal of interest

Landis, one of Larsen’s trademark fabrics, was originally woven in Switzerland but later manufacturing problems made him move the work to New Zealand. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

in new architecture and design.”

The modernist’s glass-walled buildings called for new types of fabric — curtains that let in light yet maintained privacy, upholsteries that added texture and color to the cold surfaces. But “there were no warehouses full of modern fabrics,” Larsen says. “They needed a weaver.” Larsen quickly gained a reputation as a modernist in textiles, blending natural fibers such as linen and goat hair with cutting-edge synthetics like nylon and mylar.

Famous architects began using his work in their projects. Eero Saarinen hired him to design a diaphanous veil for the unpolished white marble rooms of the Irwin Miller House (now a National Historic Landmark). Soon after, architect Louis Kahn commissioned Larsen to weave wall hangings for his Unitarian Church in Rochester, N.Y. A cubic concrete space, the church had no interior detailing to absorb its earsplitting echoes. To mute the church’s acoustics and add color to its harsh walls, Larsen picked a thick Mexican wool and wove it into a rainbow of panels that ran from crimson through gold and sea-green to royal blues and purples.

By the early 1960s, Larsen’s fabrics started showing up in the homes of famous patrons. Jackie Kennedy chose his textile “Granite” — a weave of natural, undyed yarns — to redo the White House. When Richard Nixon took office, Larsen got a call to provide Air Force One’s carpets and upholstery.

In 1969, Larsen designed upholsteries for Pan Am and Braniff’s first 747s. “Braniff wanted excitement — they wanted it to look like Latin America. Pan Am was more conservative,” Larsen says. He created demure blue stripes for Pan Am — the 747’s launch customer — and tropical pinks and oranges for Braniff. But production ran into a snag when Pan Am wanted to use a fire-resistant fabric, four times as expensive as Larsen’s preferred wool. “It was ugly and faded horribly,” Larsen says. Luckily, “the fabric failed every safety test and I wound up using wool after all.”

For the tallest building in the world, the Sears Tower in Chicago, Larsen designed 28 quilted silk hangings. Its lobby featured marble floors and a ceiling high enough for full-grown trees. The acoustics were “brutal” until his hangings softened the sound. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

Larsen excelled at adapting the newest technologies for his textiles. In 1959, he produced the first printed velvet upholstery. Two years later, he designed the first stretch upholstery. He was also first to adopt ancient techniques like batik and ikat to powerloom machines. “His favorite fabric is always the next one,” says Krista Pawar, who designed for Larsen in the 1990s.

Early on, Larsen dabbled in clothing after an upscale men’s store noticed a tie he’d woven and requested an order. The ties were an instant hit with the avant-garde. “All my heroes tended not to like ties, people like John Cage, I.M. Pei and Leonard Bernstein,” Larsen says. “And I’d see them in my ties. That was one of the best things that happened. Then I was open to working in apparel.”

Calling his clothing line “J.L. Arbiter,” Larsen spun suits out of exotic fibers and designed a line of classic cuts for women. Vogue did an enthusiastic story on the clothes. The chic department stores I. Magnin and Neiman Marcus each sampled 100 garments. “The first disappointment was when Vogue came back about six weeks later and said, ‘Now you’ve done classicism. What’s your new thing?’ ” Larsen says. When the department stores asked for an additional 1,000 pieces, he realized “we’d have to get much bigger or stop.”

Instead, Larsen turned his energy to commercial fabrics. In 1962, J.P. Stevens hired him to make towels for their new line. Betting that female buyers would be more daring with towels than with sitting-room upholsteries, Larsen created a terry-cloth weave with architectural patterns in bright avocados and ochres. His gamble paid off: Before long, the towels became best sellers.

This curtain section, woven for the Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts in suburban Washington, D.C., was a 1971 collaboration between Larsen and a hand-weaving studio in Swaziland. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

But Larsen’s designs occasionally proved too bold for sales departments. When Macy’s placed an order for a colorful Larsen fabric, it secretly told its salespeople that Larsen’s goods were fine for generating press, but not for selling to homemakers. Even when the fabric outsold Macy’s other collections, the salespeople remained wary of Larsen’s daring designs. From then on, Larsen steered clear of department stores.

Throughout his career, Larsen has maintained a connection to his Northwest roots. In the 1960s, he designed fabrics for many Seattle buildings — including Nordstrom’s flagship store and the house of Boeing President William Allen — and wove blinds and upholsteries for Roland Terry, a leading architect in the Northwest style. Terry’s houses, which complemented their natural surroundings, inspired Larsen to create fabrics with understated elegance and sunny colors to offset the Northwest’s overcast skies.

In 1996, Larsen returned to Seattle to design the carpet for the Seattle Symphony’s new home, Benaroya Hall. The same year, he began the carpet for his alma mater’s renovation of Meany Hall. On Meany Hall’s original carpet, the University had copied a Larsen print. The second time around, Larsen personally wove the fabric. “I felt it needed to be as bold as possible,” he says. He chose a large-scale pattern in vibrant reds and yellows that would lighten the cavernous space. His color scheme reflected the hall’s sunburst glass sculptures by Larsen’s longtime friend Dale Chihuly.

Larsen’s oneman show at the Louvre included a mock-up of Braniff Airlines’ first 747 cabins featuring the designer’s colorful upholsteries. Photo: Cowtan & Tout.

A man of limitless energy, Larsen is most content when engaged in many projects. In addition to running his company, he has authored nine books, traveled extensively, mentored young artists and collected rare fabrics, crafts and works of art. “Jack’s a very driven person; he was able to juggle so many things at once,” says textile expert Bronwen Solyom, Larsen’s longtime friend. “Running the business, doing his own creative design, serving on a number of museum boards. And he still found time to sit down at home for a beautiful meal every night.”

Larsen also found time to garden. After designing all day, he would retire to his rooftop terrace in Manhattan or to Round House, his 12-acre East Hampton estate. There, he kept his hands busy by weeding and planting until dark, while his mind plotted new fabrics for the company to try.

In 1986, Larsen sold Round House and constructed the four-story LongHouse, modeled on a 7th-century Japanese shrine. On the surrounding 16 acres, Larsen planted more than 1,000 flowering species and rare conifers. As both Larsen’s home and a public foundation dedicated to the arts, the house and surrounding gardens are available for public tours each summer.

These days, Larsen divides his time between LongHouse and his Manhattan loft. He sold his company in 1997 to Cowtan and Tout, but stays on as a consultant. At an age when most of his colleagues have retired to lead quiet lives, the 78-year-old Larsen keeps dreaming up new projects and pushing the limits in his life and art. “I like any extremes, the lowest or the highest,” he says. “The middle ground has always been the least interesting.”