Artistic expansion Artistic expansion Expanded Henry Art Gallery gives artists room to express themselves

The Henry Art Gallery takes a major step forward with a three-level addition.

The Henry Art Gallery takes a major step forward with a three-level addition.

A wine cooler pink Eastern sky warms as the slowly rising sun brings a glow above the spires of Suzzallo Library and bathes Red Square. The statue of George Washington, his back to Suzzallo, keeps his usual watch on Schmitz Hall and the flowing traffic on the ship canal bridge. Behind all this, cherry blossoms are in full bloom on the Quad at the University of Washington.

It would be great if this scene unfolded on Sunday, April 13. But even if it is pouring rain and the sky is murky gray and a chill wind blows, this will still be a day to celebrate.

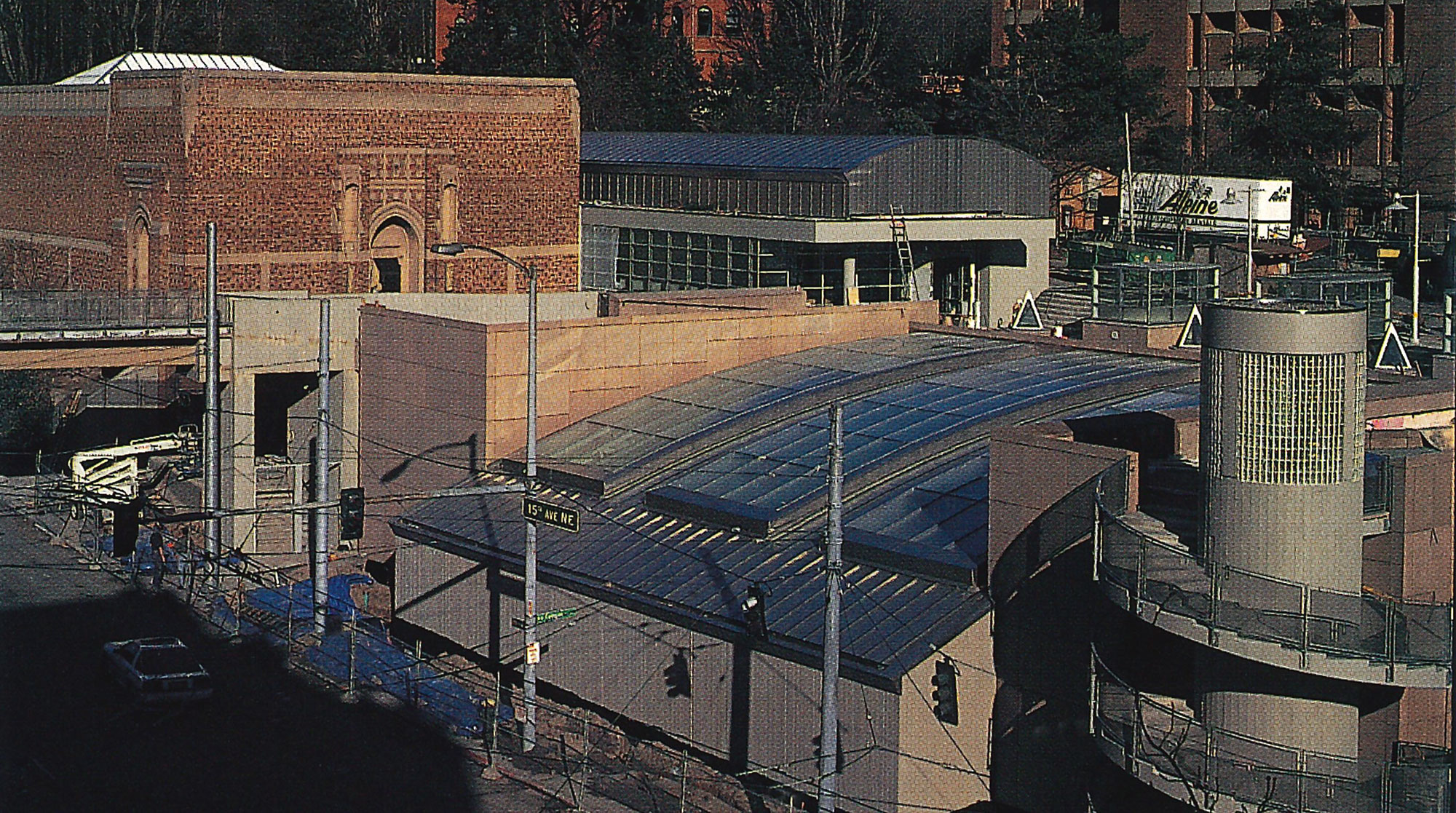

For it is the day the 70-year-old Henry Art Gallery will reopen after a major expansion and renovation. Considered by many to be one of the Pacific Northwest’s leading museums for contemporary arts, the Henry will take a major step forward as the familiar but elegant 10,000-square-foot, collegiate-Gothic red brick building is joined with a new, modernist three-level structure, the Faye G. Allen Center for the Visual Arts. The new 36,000-square-foot Charls Gwathmey-designed gem triples the museum’s exhibition space, enhancing the Henry’s ability to bring world-class art to campus.

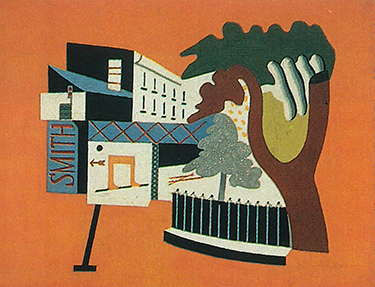

“Trees and El,” 1931, by Stuart Davis, from the War Assets Collection.

“The voice and vision of a university museum is more focused and allows for greater risk-taking and more experimentation in its exhibitions and programming,” says Richard Andrews, director of the Henry Art Gallery. “Seattle is known nationwide as a city of innovation, and the Henry, through its diverse programming, has become a vital part of the city’s tradition of creative energy.”

And the only way to keep up with that growing energy—and the art being created—was to add more space.

Physically, the Henry is a far cry from its modest beginnings in 1927 as the state’s first public art museum. The museum was created by Horace C. Henry, a Seattle builder and philanthropist, who donated his collection of primarily late 19th- and early 20th-century French and American landscape paintings (valued at nearly half a million dollars then) along with $100,000 for the construction of the museum, provided construction “commence at a very early day.” Horace Henry’s legacy lives on. As part of the inaugural exhibition, viewers will see works by Winslow Homer and Gilbert Stuart from his original collection.

The Henry was intended to be the first wing of a large arts complex at the western edge of the campus, envisioned as the gateway to campus and a bridge from the University and the community. But it was the only part of the fine-arts master plan by UW architect Carl F. Gould to be realized.

Over the years, the Henry has become one of the most prominent galleries in the Pacific Northwest, attracting more than 60,000 visitors a year despite only having 5,000 square feet for exhibitions. Since its inception, it was best known for progressive exhibition programs—its noted 1928 exhibition featuring works by the “Blue Four” (Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky and Klee) was recognized as the first significant exhibition of modern art in Seattle.

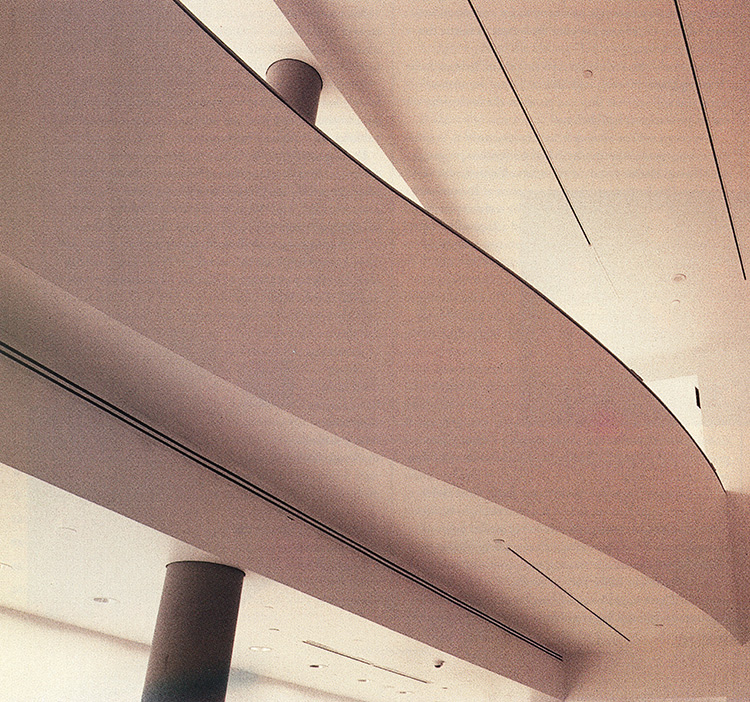

A portion of the ceiling at the Henry Art Gallery.

The new Henry’s stature will no doubt grow in concert with its larger physical space, thanks to the $17.5 million renovation and expansion project financed through a public/private partnership between the State of Washington, the UW and the Henry Gallery Association, the gallery’s fund-raising organization.

The state contributed $8.6 million over the past three years. Support for the Henry Gallery Association’s capital campaign—headed by UW Regent Sam Stroum and William True, president of the Henry Gallery Association Board of Trustees—was so strong that the campaign surpassed its goal of $23 million and raised its sights to $25 million.

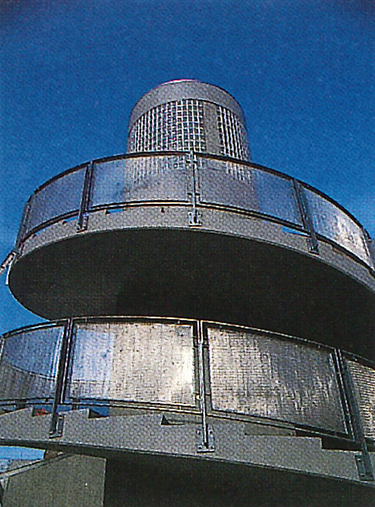

A spiral staircase is one dramatic element in Charles Gwathmey’s addition to the Henry Art Gallery.

The new Henry features renovated gallery space to properly present the museum’s permanent collection for the first time; new galleries to accommodate installations of contemporary art on an ongoing basis; improved storage and handling facilities; a 154-seat auditorium; a cafe; an academic research center; and studio space for school groups.

Gwathmey, best known for his addition to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, features as his central element the gigantic South Gallery, a warehoused-sized space in the Faye G. Allen Center. Much larger than it appears from the outside, the gallery is below grade, and its sloping roof, with three long skylights projecting above it, is similar in outline to the hillside it replaces. He himself calls it the “foothill” to the campus.

Gwathmey says the design “originates from the recognition of the existing building as a found object” and creates a “compositional whole by the addition of the new architectural form.” Using glass, buff cast-stone panels, board-formed concrete and textured stainless steel on the addition provides a dramatic visual contrast to the monumental red-brick architecture of the neighboring academic buildings.

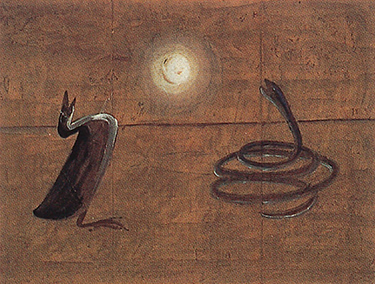

“Untitled (Bird and snake),” 1945, by Morris Graves, from the Margaret Callahan Memorial Collection.

The original Henry remains untouched for the most part, both inside and out. The museum’s main door has been moved to the long rectangular form that runs parallel to 15th Avenue N.E. behind the original building. That structure also features a loading bay—no great shakes to you, maybe, but consider that before the expansion project, everything had to enter the Henry through its tiny, old front door. That often required large exhibits and works to be taken apart, stored outside under weather protection, taken inside and then reassembled. That pain-in-the-you-know-what piece of history will make for good lore from now on.

Visitors entering the new main door have their choice: head down a bridge of stairs into the original building, whose galleries will display the Henry permanent collection; take a cantilevered stairwell to the new cafe and study area for the museum’s collection of prints and drawings; or stroll past the stairwell to a wide passage overlooking the double-height East Gallery — and taking you to the entrance of the South Gallery, where temporary exhibitions will be on display.

New senior curator Sheryl Conkelton has been working double time on since her arrival last April. For starters, there is Unpacking the Collection, which will fill the galleries of the original building.

“Untitled #228 (Judith),” 1990, by Cindy Sherman, from the Joseph and Elaine Monsen Photography Collection.

The title has lots of meanings: first, the show is drawn from the Henry’s large, rarely seen, 18,000-object permanent collection, most of which has been in storage for years and inaccessible to the public.Then there is the play of the word “unpacking,” which Conkleton uses to “examine the underlying assumptions of a word or concept.” The show now only will present some of the Henry’s substantial permanent collection but examine the process collections are built.

Another inaugural show is Inside, a group of eight to 10 installations by an international selection of contemporary artists that explore a range of possibilities from meditative beauty to physical threat, from spatial confusion to politically and emotionally charged arenas. It will run from April 13 to June 29.

In the new Media Gallery, Between Lantern and Laser: A Brief History of Video Projection will survey recent video projection works from the 1970s to the present. This show, which runs from April 13 to July 1, will exhibit single and multi-channel video, broadcast, project and installation works.

“The Henry is committed to investigating a wide range of expression in art and fostering a dialogue about the relationships between art and culture,” Conkelton says. “And now we are better equipped to explore these concepts and engage broader audiences.”

A bright day is dawning, indeed.