Liquid gray skies hang heavy over the lush forest of the Quinault Indian reservation. It’s dark as dusk standing among the crowded firs and cedars, and impossible to imagine great expanses of Pacific Ocean beaches are just yards away. It is even more surprising to see, rising from this thick swath of green, a cabin that seems to have sprouted from the forest floor.

This deceptively simple 18-by-18-square-foot wooden box, along with the architect waiting within, is the reason Boaz Ashkenazy, ’02, a part-time lecturer for the University of Washington Department of Architecture and partner at visual communications firm studio/216, and videographer John King have driven deep into Washington state’s coastal rain forest on a damp August day. They’ve come to this remote area near Forks, Wash., accessible only by miles of roller-coastering dirt road, to learn more about a unique brand of modernist architecture native to the Pacific Northwest.

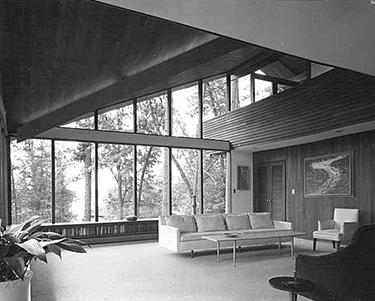

The cabin, which is known as the Raft River Retreat and was designed by Arne Bystrom, ’51, captures the spirit of Northwest Modernism perfectly. The cabin was built by Bystrom and his family over a period of seven years and completed in 1978. Every detail has purpose and character. Each nook is filled with a found stone or piece of driftwood. Scarce daylight magnified by the glass ceiling inspires the aromatic cedar-planked walls to cast a warm, red glow. Rail-less decks extend into the rain forest, emphasizing the cabin’s intimate connection to the landscape.

“It’s an amazing little cabin,” Ashkenazy says of the hand-built cabin.

Its clean lines and lack of ornamentation instantly classify it as part of the modernist movement. But the oversized 4-foot-long cedar shakes adorning the building indicate it is more than that. Such regional touches are the hallmarks of a style influenced by necessity and determined by a climate that demands concessions.

Ashkenazy is relying on Bystrom, one of the leading proponents of Northwest Modernism of his time, to offer a deeper understanding of this distinctive style of architecture — the focus of the documentary scheduled for release this spring called “Modern Views: A Conversation on Northwest Modern Architecture.”

Ashkenazy is relying on Bystrom, one of the leading proponents of Northwest Modernism of his time, to offer a deeper understanding of this distinctive style of architecture — the focus of the documentary scheduled for release this spring called “Modern Views: A Conversation on Northwest Modern Architecture.”

Ashkenazy and King are joined by David Miller, professor and chair of UW’s Department of Architecture and partner at Miller Hull. He has also taken an active role interviewing the architects featured in the film, which was funded by the Department of Architecture, part of the UW’s College of Built Environments, and produced by studio/216. The team hopes the documentary will inspire appreciation for what remains a mostly hidden secret of regional gestalt.

“I’d like to see students reconnecting with architects and architecture from this time and place,” Miller says. “I’d like individuals interested in modernism to recognize the profound impact a site has on its designers and what a magical place the Pacific Northwest is for creating art and place-making.”

Bystrom is one of five architects Ashkenazy and others interviewed for the documentary. Wendell Lovett, ’47, Gene Zema, ’50, Ralph Anderson, ’51, and Fred Bassetti, ’42, also shared their perspectives. These five hail from what’s called the Northwest School, the collective drivers behind the new regional identity that began to emerge in the late 1940s. All are the products not only of the Pacific Northwest environment they lived in, but of the University of Washington as well, which proved an effective breeding ground for the burgeoning style.

“I believe the five living architects that we interviewed, in addition to Paul Thiry and Paul Hayden Kirk, were the most gifted designers, and the most prolific, of the Northwest School,” Miller says. “This group had the greatest influence on their peers and on the next generation.”

Thiry, ’28, and Kirk, ’37, both deceased, are each heralded for their contributions to Northwest Modernism. Thiry is credited with introducing European Modernism to the region. Kirk’s work is exemplified by the Magnolia Branch of the Seattle Public Library and the UW’s Edmond Meany Hall. Like all five of the architects interviewed for the documentary, Thiry and Kirk also received their formal architecture training at the UW. Professor Lionel Pries is attributed as a tremendous influence upon this group and others who propelled the style forward.

The documentary will focus on the work of Lovett, Zema, Anderson, Bystrom and Bassetti during a 20-year period, from 1950 to 1970. Particular traits set their collective works apart from what was happening in Europe, on the East Coast and in California, where the modernist movement had already taken root.

The Pacific Northwest environment, landscapes and wet weather all shaped their designs in a similar way. It guided the materials they used. Though concrete and steel were all the rage on the East Coast and in Europe, natural materials took precedent here.

“The group had a passion for materials,” Miller notes. “Wood shingles: Bassetti and Bystrom; cedar siding left natural or stained, never painted: Lovett, Zema and Anderson. Lovett roamed the farthest stylistically.”

It influenced the way they sited their buildings, exemplifying what Grant Hildebrand, a professor emeritus in the UW Department of Architecture and historian, coined “refuge and prospect.” They located their buildings to offer protection from the rain, while emphasizing the vistas of the surrounding landscape, and inviting the outdoors in.

Ashkenazy observed many common themes recurring as each interview was conducted, especially the challenges presented by the Pacific Northwest’s famous rain. A steep 6/12 pitch — a roof rising 6 inches vertically for every 12 horizontal inches — became a simple and common solution for sluicing rain from roofs. Over time, these influences helped shape each individual’s architectural style. While remaining distinctive, all practiced Northwest Modernism.

“These are the guys that really put Seattle on the map.”

Boaz Ashkenazy, UW lecturer

“It’s a more subtle modernism,” Ashkenazy explains. “It’s not screaming at you.”

Perhaps it was this need for ingenuity in fighting the elements that led to further out-of-the-box thinking. This group was at the forefront of prefabrication long before it was on every designer’s lips. For those of the Northwest School, creating a mobile kit-of-parts that could be assembled easily was often the most efficient way to build on sites that were difficult to access.

“The pre-fab stuff for these five wasn’t about the fact that it was pre-fab, it was about building all those trusses themselves, putting it on their cars, taking them out to islands, putting it together themselves,” Ashkenazy says.

Many of the documentary’s subjects also built sustainable and green projects long before such labels became pervasive.

“Those guys will tell you, ‘It’s always been green building,’ “ Ashkenazy says. From using locally available materials to purposefully siting their structures for optimal light and heat from the sun, members of the Northwest School relied on time-tested strategies. But they also embraced new ideas. Bystrom’s solar-panel-covered Sun Valley House is to this day an innovative exercise in sustainability.

It was only a matter of time until their work earned notice on the national stage.

“These are the guys that really put Seattle on the map,” Ashkenazy says.

It began with recognition in The Seattle Times through a program known as “Home of the Month,” the first of its kind nationally. In partnership with what was then the Washington State Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, now AIA Seattle, the newspaper began recognizing a different residence each month starting in 1954. It also saluted an annual Home of the Year, the first being Gene Zema’s own Sheridan Heights home.

These five architects earned numerous awards throughout their careers, and their work was celebrated in major publications, including Life magazine, Sunset, House Beautiful, House & Garden and Architectural Record. They were regularly honored by the AIA, and their designs were selected for Home of the Year. Bystrom’s Raft River Retreat received the American Institute of Architects’ National Honor Award in 1979, the most prestigious form of recognition the organization gives to an individual building.

The subjects of the documentary have left a legacy beyond their award-winning buildings, in the form of another generation of architects in the area that followed in their footsteps, building upon a style they established. Ashkenazy envisions a second documentary that would capture the work of this generation of Northwest architects.

A potential sequel would focus on Jim Olson, ’63; George Suyama, ’67; Gordon Walker; Rick Sundberg, ’66; and David Miller and Bob Hull. Two of their firms, Miller Hull and Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen, have received AIA Architecture Firm Awards.