The way Alfredo Arreguin slaps his knee and laughs his high-pitched laugh, you would never suspect all the abandonment, pain, heartbreak and discouragement he experienced as a child. Or how his unlikely journey from his native Mexico to the University of Washington 40 years ago helped put him on the road to becoming one of the greatest Hispanic artists of our time.

Arreguin’s list of credits is staggering: his 1992 oil on canvas painting Sueno (Dream: Eve Before Adam) is in the permanent collection of the National Museum of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution. His paintings hang in the world’s most prestigious galleries, he twice received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and he owns 19 national awards and prizes, many for his paintings on the environment.

He’s likewise heralded for his community work, which ranges from donating works of art to non-profit organizations to teaching seriously ill patients at Seattle’s Children’s Hospital how to make forms from clay.

His success as an artist and the embrace from the community are certainly heartwarming, but what makes Arreguin glow is that he has a family of his own now: a loving wife, painter Susan Lytle, and 23-year-old daughter Lesley, a burgeoning artist in her own right (along with two grown children from a previous marriage). It’s a huge change from the pain Arreguin grew up with, which started when his parents split when he was just a toddler. Raised by his grandparents until their deaths three days apart in 1948, he then bounced from living with his mother and stepfather to moving in with his father and stepmother when he turned 13. That last move came as quite a surprise, since Arreguin was told five years earlier that his father had died.

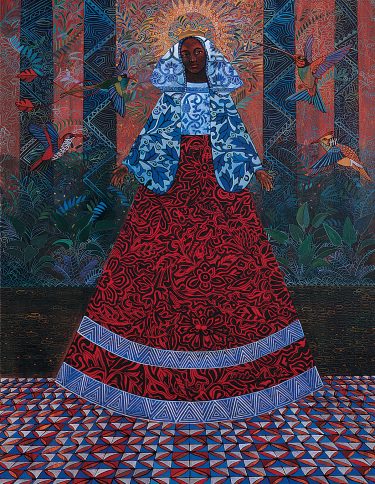

Alfredo Arreguin’s 2000 painting “Camilia #2.”

“It was the story of my life,” Arreguin says, relaxing at his modest red brick home in North Seattle. “I have always been alone and not really part of a family. It was very devastating. When I later came to the U.S., I was a foreigner. And I wasn’t part of Mexico, either. I didn’t feel like I fit in anywhere.”

The reunion with his dad, a prominent Mexico City businessman, was anything but warm. “I don’t think he’s my son, but I will help anyway,” Arreguin recalls his father telling him. Soon after Arreguin’s arrival in Mexico City, his father promptly sent him to a boarding school because they fought so often. Later, he got his son a construction job at a dam being built in the wild mountains of Guerrero state. The work was hard but being in the jungle made a lasting impression on Arreguin that would surface in his paintings years later.

He did not last long with his disapproving father, who considered his teenage son a troublemaker.

“My dad wanted to get rid of me,” Arreguin recalls. “I was causing him trouble, I did poorly in school, and he wanted me out.” So Arreguin’s father gave him the money to start a business. Arreguin responded by blowing the windfall on a convertible and going to Acapulco to be a sometime tour guide.

There, he met a vacationing Danish family from Seattle, who befriended him and invited him to visit them in the Emerald City. During Arreguin’s first trip to Seattle, they took him to the UW. He was wowed.

“What a great opportunity it was,” he says. “I loved it.” Here was his chance to get away from his father and start a new life.

With the help of the late Sen. Warren Magnuson, ‘29, Arreguin got his papers and moved to the Northwest. He wasn’t allowed to begin at the UW right away as the admissions office told him he needed to get his high school education in order. So off he went to Edison Technical School (now Seattle Central Community College) for two years. Once that was behind him, he hit another detour when he was drafted by the Army and sent to Korea, where he spent 13 months “trying to convince them I wasn’t the enemy.” He struggled to learn English, combating blatant discrimination and getting used to life in the military, while fully taking advantage to explore Asian culture every chance he got. It, too, would have a profound effect on his later works.

When he returned to the States in 1961 with the backing of the GI bill, he dove back into campus life. He took classes during the day while working nights at Campos, a local Mexican restaurant, living in a small room above the kitchen. He also worked as a part-time janitor at Bethany Community Church near Green Lake for $100 a month. Arreguin first studied architecture, a profession backed by his domineering father, then gave interior design a try before switching to painting.

“Madona Afro Latina,” 1994.

But settling on a subject wasn’t his only problem. He was also having a hard time in Seattle, not exactly a mecca for Hispanic culture. “It was very strange when I first arrived here,” he says. “I was so happy when I finally met another Chicano student here. There just weren’t many of us.” He joined a UW club for foreign students, the Cosmos Club, and got involved in student protests that later engulfed the campus. But it only helped a little.

“He was like a fish out of water,” recalls Michael Spafford, a retired UW art professor who taught painting and drawing. But in the classroom, Arreguin “stood out as a student and as a person because he was very intense,” Spafford says. “He had a very big ego, he was stubborn—like all good students. He was very focused on being an artist. If you gave him an assignment, he would do more than you assigned.”

Like many painters at the time, Arreguin churned out abstract expressionist works, squishing thick paint out of tubes and mashing it onto large pieces of canvas.

“They were large, broadly painted, with lots of emotion,” says Alden Mason, a retired UW painting professor who was one of Arreguin’s mentors. “Very passionate and intense.” Arreguin also painted personal subjects, such as people, taverns and scenes from daily life. Interestingly, like another of Mason’s celebrated students, Chuck Close, ‘62, Arreguin would later change his style 180 degrees to what it is today—exquisitely lush jungle scenes, colorful in their detail, focusing primarily on images from the environment. He employed extravagant patterns and colors, drawn from many cultures, mostly pre-Columbian, but also from Japanese woodblock prints, Islamic tiles and Pacific Northwest formline drawings.

What helped him find his intensely personal vision was a meeting during his time as a UW student with Elmer Bischoff, a well-known American figurative painter. Bischoff saw Arreguin’s early, abstract works and told him to forget about being an artist. “Do what you are good at!” he scolded Arreguin. “Do what you believe in.”

“Chiwana,” 1999.

Arreguin, who first demonstrated a talent for drawing and painting when his grandfather enrolled him as an 8-year-old in the Morelia School of Fine Art, heeded the advice.

He quit painting for three years, concentrating on drawing instead.

“I thought I heard too many voices other than mine,” says Arreguin, who received his bachelor’s degree from the UW in 1967 and his master’s of fine art in 1969. “I had to get away from painting for a while.”

During this period, he noticed patterns on a tile floor and it dawned on him that the patterns were art in themselves, and worth further exploration.

He developed a unique style of “pattern paintings” that was heavily influenced by Mexican and Latino icons, jungle rainforest experiences from his youth, and the Pacific Northwest. His complex compositions were filled with colors that dance between hot and cool. And he frequently incorporated concealed iconic or religious imagery behind an overlay of intricate design.

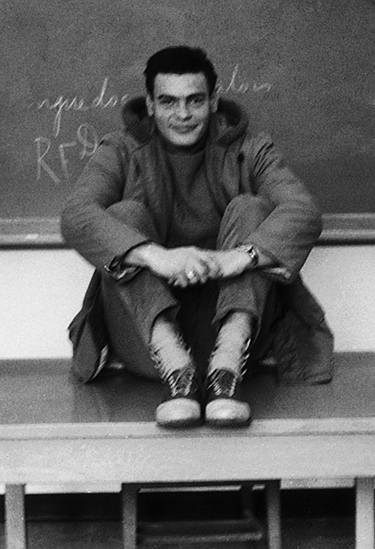

Waiting for his English 101 teacher to show up, young UW student Alfredo Arreguin was one of just a handful of Hispanic students at the UW in 1962. Photo courtesy Alfredo Arreguin.

His big break came in 1977, when a museum in San Francisco featuring Mexican art wanted to show his work. That led him to a curator in Washington, D.C., who selected him as one of three American artists whose work would be shown in Paris.

“I consider him an artistic genius,” says former Washington legislator Phyllis Gutierrez. “He is creative and most of all, he paints from the heart, so it brings out the traditional feeling that he has for our Mexican culture, but also the special feeling for the Northwest.”

“I often wonder,” muses Roberto Maestas, ‘66, ‘71, executive director of El Centro de la Raza, a Seattle-based Hispanic community service agency, “without Alfredo, how would we have projected the brilliant art that characterizes Mexico. In this part of the U.S., Chicanos have been invisible for so long, even though we have been here for many, many years.

“Because of his political statements and his artistic talent, Alfredo has helped put Washington on the map. He has paved the way for appreciation for other Chicano artists. He is the dean of Latino art in the entire Northwest.”

Arreguin draws repeatedly on images of the Mexican jungles and rainforests of his childhood in the state of Morelos, where he was born. In contrast to his reputation as a rowdy kid, he uses a deliberate, painstaking method in creating his paintings. Looking at a blank canvas, he starts with a grid pattern, using intricate detail and a wild array of colors and patterns to develop flowing, nearly “hallucinatory states of complexity and beauty,” says art critic Matthew Kangas. He went so far as to call Arreguin “a magic realist.”

Arreguin kept painting but needed to take on odd jobs to support himself and his wife in the early 1970s, while living in “a shack” in North Seattle. “We were poor,” he says, “but we were happy. We didn’t have much, but we were painting.” As more people discovered his talent, the need for other jobs fell by the wayside. He proudly says the last “real” job he had was building speaker cabinets in 1974.

In 1979, he won the Palm of the People Award at the International Festival of Painting in France. The following year, he won a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. In 1986, he was the recipient of the Governor’s Art Award from the state of Washington.

“Arreguin paints the natural world not as a scientist, but with the unbridled enthusiasm of a child fascinated with every detail and willing to believe in forces that are unseen but sensed,” says Andrew Connors, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution. “His paintings unleash our imagination and free us to envision an ideal world by celebrating both the ethereal and the tangible in the contested world around us.”

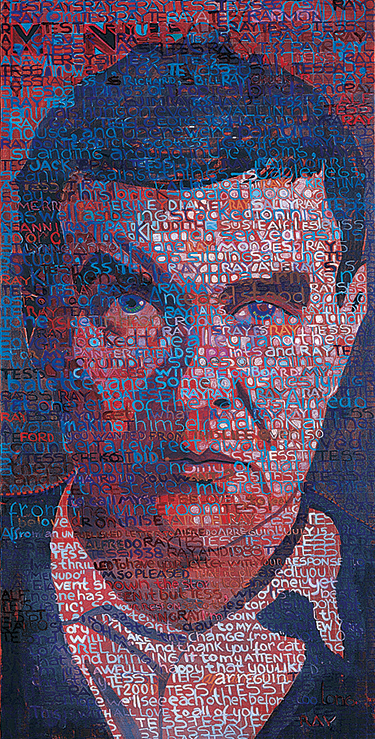

“Mi Amigo Ray,” a portrait of writer Raymond Carver, 2001.

Over the years, Arreguin’s paintings evolved to incorporate more Pacific Northwest environmental themes. He regularly features salmon, floating in streams, coming at viewers at all angles, sometimes brazen and other times barely seen.

His famous salmon triptych, Hero’s Journey, was done for his late friend Raymond Carver, who died of cancer in 1988, and his wife, poet Tess Gallagher. That painting appeared on the cover of Carver’s last book of poems, A New Path to the Waterfall.

Although much of his work of late has centered around the Northwest, his devotion to the local Latino community has been legendary. His poster marking the 20th anniversary of El Centro de la Raza featured a magical horse named after Emil Zapata’s horse, which escaped into the mountains after the Mexican revolutionary was killed in a 1910 ambush.

“Emiliano Zapata is the foremost symbol in Mexico of the people and the land,” Arreguin explains. “Whether we own it or work it, the land is the essence of life. Like Zapata, El Centro de la Raza grew out of the struggle for land for our people. Zapata exemplifies compassion and the struggle for justice and dignity, so it is a fitting image for El Centro de la Raza, whose commitment to justice is in keeping with this spirit.”

Arreguin, who has offered the family of Cesar Chavez artwork he did of the late civil rights leader to help raise funds for the United Farm Workers movement, received one of his highest honors in 1997. He was presented then with the “Ohtli,” an award created by the government of Mexico to recognize the altruistic activity of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans who have worked consistently for the benefit of their communities throughout the U.S.

Exalted as that honor was, it was nothing new for Arreguin, who still works out of the basement of his home and uses cut Coke cans to hold his paint. He created the official commemorative poster for the 1989 Washington State Centennial. The state Legislature gave him its Humanitarian Award for his contributions to Hispanic culture. And so much more.

Yet what may account for even more joy is that he has a relationship with his cantankerous father, now 96 and still living in Mexico City. Go to his dad’s opulent home today, and you will find the walls covered with Arreguin originals. The big thaw started in 1994, the year the Smithsonian purchased a painting of Arreguin’s. “If I had only known of your talent, I would have pushed you,” Arreguin recalls his father telling him, laughing at the memory. “I always thought you were fooling around.”