For grad students,

the reward is worth

the hardship

For grad students,

the reward is worth

the hardship

For grad students, the reward is worth the hardship

Despite tight finances, incredibly long days and stiff competition for funding, graduate school has never been more popular.

By Jon Marmor | Illustration by Christin Ranger | Dec. 1994 issue

During her first year at the University of Washington, Judy Pine walked all over campus every chance she got. The "Quad," Drumheller Fountain, everywhere. This wasn't sightseeing—it was the only way she could stay awake. "If I sat down, I would fall asleep," she says.

Pine was suffering from a condition currently affecting 7,815 people at the University of Washington. She is a grad student.

“Graduate school can be fun, but you also may not have much of a life,” says David Burgess, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in comparative literature. “It can be pretty grueling.”

Yet despite the financial hardship, incredibly long days spent on school work and final projects, stiff competition for often tight funding, and part-time jobs, graduate school has never been more popular. For Autumn Quarter 1994, more than 17,300 applications poured into the UW graduate school admissions office.

“Ten years ago, we used to get 10,000 applications,” says Joan Abe, director of graduate admissions, “and now we are approaching 18,000. Some faculty here tell me if they had applied to get in here now, they couldn’t make it. Too competitive.”

Born and raised in Eureka, Kansas, Pine had gone’ to Kansas State University for her undergraduate schooling, then spent six years as a lieutenant in the Army. It took her two tries, but three years ago, Pine was one of the fortunate ones to get into the highly competitive anthropology department.

“When I left school, it was with a lot of debt. But I also had some of the best times of my life during graduate school.”

Don Whitney, School of Social Work

She was thrilled. She liked Seattle, loved her subject, and adored the adviser she would be working with—Graduate School Dean Carol Eastman, who has since left the UW to become senior vice president of the University of Hawaii.

Then reality hit Pine flush in the face as if she had stepped on a rake. With funding in her department very tight, she had to get a job. She worked in a fast-food restaurant before landing a job as an $8-an-hour security guard—on the graveyard shift.

“Money is a problem,” acknowledges Esther Luttikhuizen, who received her master of fine arts in 1993. “You hope you can get a TA position, but you need loans and take work-study jobs.”

Finances are perhaps as big a challenge as any graduate program itself. Currently the tuition is $4,566 for residents and $11,436 for non-residents. UW Graduate School officials estimate that it costs about $11,000 a year in room, board, books and transportation. Student loans are one way of paying the bills, but they leave a legacy. According to the U.S. Council of Graduate Schools, students earning a Ph.D. degree in 1990 had an average debt of $5,910.

Funding graduate fellowships is an ever-present problem. During the $284-million Campaign for Washington, the UW’s first major fund drive, the University was able to raise $12.9 million for fellowships. But the goal was even more ambitious. UW officials had wanted $34 million for graduate student support.

“You learn to live very inexpensively,” says Don Whitney, director of student services for the School of Social Work and a former graduate student himself. “I ate a lot of macaroni and cheese out of a box. And when I left school, it was with a lot of debt. But I also had some of the best times of my life during graduate school.”

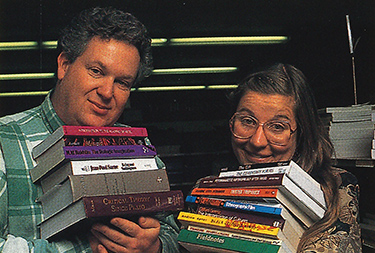

UW graduate students David Burgess and Judy Pine at the University Book Store.

Pine can laugh about it now, but that first year nearly did her in. “I had no time to sleep,” she says. “My first year was spent in core courses, which means I had hundreds of pages of reading for homework, plus several 20-page research papers each quarter. Roughly four nights a week, I worked from midnight to 8 a.m. as a security guard, and then I’d shower and change, and come to campus.

“I was a zombie, [but] it may have been a good thing. I was in such a daze, I was too busy to be stressed out by my program.”

Of course, not everyone has it that bad. Some departments provide lots of funding for their graduate students—with TA or RA jobs, fellowships and the like. All 40 incoming graduate students in chemistry, for example, were recruited with the promise of financial support from the school, and all will be teaching this year. After that, chemistry students are supported with a variety of positions paid with federal funds and private foundations.

“But we pay less to our students than many of our peer institutions,” says Chemistry Professor Leon Slutsky. “We have limited funds, and sometimes students we are interested in will go somewhere else because the funding is better.”

But, in comparative literature, teaching assistant jobs are available only to Ph.D. students and only for a limited time. Finding enough money to survive has drained a lot of time and energy out of Burgess, who is married and has two young children.

“Oh, it ain’t easy,” he groans, especially last summer, when his car broke down and he needed to have his transmission rebuilt. “We were already living on borrowed money and then that happened. It is a struggle to pay bills.”

And then there is daily life. Or Burgess’ definition of it during the first three years of his Ph.D. program. Up at 8 a.m. and off to school. Home at 6 p.m. for dinner. Back at school at 7 p.m. Home at 11 p.m. Read for a few hours. In bed at 1 a.m. in time to do it all over again. Weekends were only slightly less hectic. On Saturdays he would spend the day with the family, then head to school at 4 p.m. and work late into the evening. On Sundays he took a break, not heading to school until 1 p.m.

“I do have to say that graduate school is heaven and hell.”

Judy Pine

“I didn’t give enough attention to anything else in my life,” Burgess says. “It was a grueling and oppressive schedule, a very difficult year. I don’t necessarily like the choices I made, but I didn’t see that I had any other choices if I wanted to get done in a reasonable amount of time.”

Reasonable isn’t a word many would apply to the regulations attached to the grants graduate students seek. Some prohibit outside work, which has Pine wondering how she was supposed to exist on her grant, which paid between $600 and $700 a month but didn’t allow her to have any employment. “My husband and I have gone through our savings in the last two years,” she says.

She picked up $5-an-hour jobs grading papers for teachers, doing library research jobs for others—anything to make a little money and still stay within the bounds of her grant.

This year she does have some help—a job as president of the Graduate and Professional Student Senate. For putting in at least 20 hours a week, Pine receives a tuition waiver.

But the job adds substantially to her workload. She is busy fighting for medical benefits for TAs and RAs, reasonable family housing rent and other issues related to graduate student life.

“I have gone weeks without seeing my husband,” says Pine. “I have to say—it is hell to be so poor. I am 31 years old, and I never thought I would be so poor at this time in my life. My husband and I want to buy a house and want to have a family some day, but there is no way we could qualify for anything.

“We have also gone without medical insurance, and that is hell. I think the great majority of grad students don’t have health insurance because they can’t afford it. There was a time when I went five years between getting my eyes checked. I haven’t had dental coverage in years.”

But no matter the constant, gut-wrenching, sleepless nights worrying over money, or the 45-cent boxes of macaroni and cheese consumed for dinner, these people love grad school and the intellectual stimulation and energy it brings them.

“It is really exciting to be in an environment where everyone is focused,” says Luttikhuizen, who surprised herself with her development during her two years of graduate school. “Your work gets challenged—they try to unhinge you and pull the rug out from under you, because they want you to explore different ideas.

“It was very stimulating. I loved it.”

Burgess’ eyes light up when he speaks about his latest research passion—psychoanalysis in literature. Yes, there was pressure, and money problems, and 18-hour days away from his kids. But there are rewards, too. “I get a real charge out of it, that’s for sure,” he says. “I love what I am doing.”

Pine also is passionate about her studies. “The reading, the work, talking with faculty—that is why I am here,” says Pine. “But I do have to say that graduate school is heaven and hell.”