When pediatric geneticist Darrell Salk arrived for his COVID-19 vaccine at UW Medical Center-Montlake, he was reminded of similar immunization lines from childhood.

He recalled scenes of grade-school students in the early 1950s cuing up for their polio shot. 1952 had witnessed one of the worse outbreaks of polio in the nation’s history. His father, Jonas Salk, had just developed a vaccine and it was entering clinical testing. As a major national field trial was organized to evaluate its safety and efficacy, parents enrolled their children—more than 1.8 million first- and second-graders, in a double-blind trial, with no certainty of any benefit. They hoped to save their children from paralysis, iron lungs, metal leg braces or weakened limbs that polio brought.

His father had been studying polioviruses since 1948, and was determined to put an end to infantile paralysis. After Jonas Salk had reached the point in his research where he believed the vaccine could prevent polio infection, he vaccinated himself and his laboratory colleagues. His family was next. Darrell Salk, a spindly 6-year-old at the time, received his dose at home at the kitchen table.

In adulthood, Darrell Salk, like many of his relatives, chose a career in medicine. He did his residency in Seattle in the mid-1970s, attracted to the UW pediatrics program after hearing pediatrician and psychiatrist Michael Rothenberg speak on how physicians can gain the trust of infants.

Salk took to heart Rothenberg’s advice on caring for, taking an interest in and interacting with children and parents—and not pretending to know it all, but being willing to find answers for patients.

“The public response was unified against polio. Almost everyone wanted to participate in the effort.”

Darrell Salk

Salk wanted to train at a place that took this approach to medical practice, so he drove his pickup truck, with its yellow homemade cover, from Baltimore to Seattle.

Salk went on to a career in teaching, practice and research and recently retired from the UW School of Medicine faculty. In addition to his work in medical genetics, Salk has written on the history of polio and its prevention, and on vaccination development generally, inspired by his own family history.

Paralysis from polio, he explains, was rare before modern sanitation. Babies were exposed to the virus while still protected by maternal antibodies.

When summer outbreaks started surfacing in the United States in the mid-20th century, public health departments closed swimming pools, movie theaters and beaches.

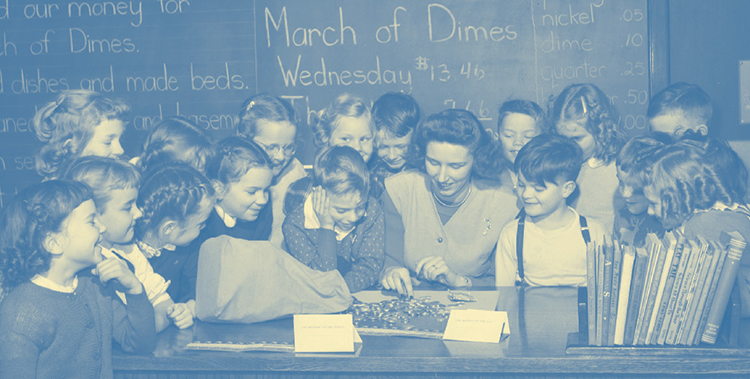

The March of Dimes allowed children and members of the public to raise money to support the eradication of polio. The funds they raised helped with the development and distribution of the Salk vaccine.

The American public, Salk says, rallied to end the threat of polio. Families pressed coins into “Join the March of Dimes” collection cards. Mothers canvassed door-to-door to raise donations.

Critics predicted the Salk vaccine would be ineffective because it was not based on live viruses. Clinical trial evidence suggested otherwise.

By 1955, the killed-virus vaccine was pronounced a success, heralding not only the end of polio outbreaks but also a new way of thinking about immunizations.

“Church bells rang, parades were held, and people danced in the streets,” says Salk. “People welcomed the vaccine with relief.”

It’s hard not to compare the country’s reaction to polio epidemic of the past century and the present coronavirus.

“The public response was unified against polio,” Salk says. “Almost everyone wanted to participate in the effort.” Today, while some countries have created a uniform approach to the coronavirus, the United States response has varied, he says.

“President Franklin D. Roosevelt understood polio first-hand,” Salk noted. “He had suffered, and did not minimize what was happening. He took action. In addition to leading government efforts, he converted his own personal property [Warm Springs] into a place where patients could have rehabilitation.”

In contrast, the early months of the coronavirus pandemic were met with the White House “ignoring, blaming and hoping it would go away,” Salk says.

Under previous administrations, the country had been planning for the eventuality of a pandemic, says Salk. Infection experts predicted that some sort of animal-to-human virus transmission would spill over and become a brand new, fast-spreading human-to-human disease.

Ebola, swine and avian flu, and earlier outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS, were warnings. Public health officials had forecasted a deadly pandemic that would arise and disrupt hospitals, schools, transportation and businesses. Nevertheless, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention readiness efforts were disbanded before the present pandemic.

“That was why the country was so unprepared,” Salk says.

Seattle school children joined a nationwide effort to collect money for the March of Dimes to help people with polio. Here, second-graders at Loyal Heights Elementary look on as their teacher counts the money they raised.

Compared to the seven years it took his father to develop a polio vaccine, the pace at which coronavirus vaccines were designed and tested was phenomenal. The speed bump was getting them out to the public.

Many decades ago, when the polio vaccine became available, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis distributed it through a coordinated, centralized national system that attempted to be fair. But disparities still existed, as is also the case today with coronavirus vaccines, Salk says.

“The coronavirus distribution is not yet as efficient or equitable as we would like it to be.

“But vaccine confidence is growing and the numbers of people willing to be vaccinated is definitely up,” he says. “There is now a routine system that is set up and working.”

“I’m so pleased at Biden’s response overall to the pandemic,” Salk says. “He applied what had already been known and what advisors had been saying for more than a year.” The government is addressing concerns about vaccine manufacturing quality at some plants and unrelated clotting problems in a small percentage of recipients.

In addition, lessons learned from the polio epidemic are guiding public health today. Polio surveillance set the stage for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention models. Testing and approval of the polio vaccine was a model for Food and Drug Administration functions.

On the downside, public anxiety about vaccines arose during the polio eradication campaign. This is because legal issues regarding live polio vaccines, an alternative to the Salk vaccine, had a watershed moment during the mid-20th century, Salk explains. Live polio vaccines carry a risk of causing infection. Killed-virus and other non-infective vaccines, taken for granted today, became prominent because of what took place back then.

While present-day vaccines must pass rigorous safety standards, getting immunized is a personal choice, and hesitancy about getting a shot can be hard to overcome.

“Most people have a minimal reaction to the COVID vaccines,” Salk says. “Typically it is a sore arm or a minor fever. That means the vaccine is working as it should to activate your immune system. The biggest risk of a COVID-19 infection is death. Compare that outcome with the outcome of a treatable reaction to the vaccine.”

“I wouldn’t bet my life or the life of someone I love by not getting vaccinated. That’s not a good bet.”

Darrell Salk

Salk believes it is unwise to play the odds with the pandemic coronavirus: “I wouldn’t bet my life or the life of someone I love by not getting vaccinated. That’s not a good bet.”

“Getting vaccinated against coronavirus is the right thing to do,” Salk says. “Get it for your own sake, to protect your loved ones, and to contribute to ending the pandemic.”

Now that he is fully immunized, Salk continues to wear a mask and follow other infection control steps to try to set an example.

“People who are vaccinated can feel less worried because they have an added layer of protection,” he says. “But given variants in the virus and individual differences in immune responses to the vaccine, there is a still a risk of infection.”

Because pandemic control was not achieved early on, Salk says, it allowed time for mutant strains to emerge. This could have been predicted, he noted, because the nature of coronaviruses is to mutate to survive.

They are unlike polioviruses, which his father discovered come in only three separate types, one more serious than the other two, according to Salk. Jonas Salk had applied his energy to the tedious task of determining these different types. The findings led to his 3-in-1 vaccine. The polio vaccine blocks the virus from getting into tissues where it can cause paralysis.

For polio, Salk said, infection and disease are not always synonymous. Respiratory illness vaccines are different and must stop the infection itself.

The approach that scientists have used to create the presently available COVID-19 vaccines should make it quicker to make changes in them to guard against infection by variant strains.

“The mRNA vaccines tell our cells to produce proteins identical to the outside of the coronavirus,” he says. “The body responds to this product and creates protections against the whole virus.”

These current vaccines are different from previous methods that grow viruses and then weaken and inactivate them on a large scale. Faced with a variant, it takes a while for manufacturers to update the vaccine using those methods. In contrast, mRNA vaccines seem to be more like a drug than a biological. Developers can build a newer mRNA version and test it right away to see if it works against the variant. This is not true with biologicals.

“RNA vaccines are manufactured, not grown,” Salk says. “They are based on a chemical aspect of the virus that they are up against.” Researchers can obtain the sequence of a variant mutation in the coronavirus, remodel the RNA vaccine accordingly, then verify if the sequence is correct. The process is a faster way to produce newer versions of a vaccine and it’s easier for quality control, Salk says.

Meanwhile, scientific ingenuity never slows down. Computer-designed nanoparticle candidate vaccines, like those heading out of the UW Medicine Institute for Protein Design, and second-generation RNA vaccines that are shelf-stable, could further stock the world’s toolkit against coronavirus variants.

At present, Salk says, no scientists know for sure how long vaccine-mediated immunity to COVID-19 will last. Levels of antibodies—the virus fighters—could drop, and booster shots could be needed.

“Coronavirus immunization strategies might need more than just a prime and one boost, and are likely not an ‘all I need for the rest of time,’” Salk says.

“There’s no reason to believe, based on experience to date, that COVID-19 will not be around for a while,” Salk adds. “It possibly could become a seasonal disease. We’ll need to get on top of it faster when outbreaks occur. It is more likely to be like influenza, in the background all the time. That is the typical behavior of respiratory viruses.”

It is possible that people will need to get regularly scheduled coronavirus vaccines, just as they do for flu vaccines. Salk explained that annual flu shots are advised because people need to maintain a high level of circulating antibodies against flu viruses. When the flu gets into the body, it immediately starts acting, and a nimble immune response is required to fight it off. If not, the virus gets the advantage. While not yet certain, the same may be true for fending off the coronavirus.

“The immune cells might not have the leisure to say, ‘Hmm, what is this and what do I do to respond?’” Salk says.

In contrast, adults don’t need repeated doses of the polio vaccine. A polio vaccine doesn’t have to keep the poliovirus from becoming implanted. There’s plenty of time after exposure for the immune system to recognize the poliovirus and crank up the antivirus machinery.

While the rate at which vaccinations are now being administered provides some encouragement, predicting the future course of the coronavirus remains uncertain. After more than a year under pandemic constraints and isolation, many people are fatigued and eager to become more mobile, sociable and engaged in a broader world. They also never want to go through something like this again.

“Will there be another pandemic?” asks Salk. “It depends on how careful we are.”

At top: A young Darrell Salk receives a polio vaccination from his father, Jonas Salk. (Family photo)