On a rainy January afternoon, 16 second-graders in matching gray sweatshirts file into a bright classroom decorated with international flags, fairy lights and a multicolored rug covered in geometric shapes. Twice a week, the children visit this room to study something overlooked in most American schools. Mr. Laster, a young teacher with dreadlocks gathered into a spiky bun, begins, “Welcome to Identity.”

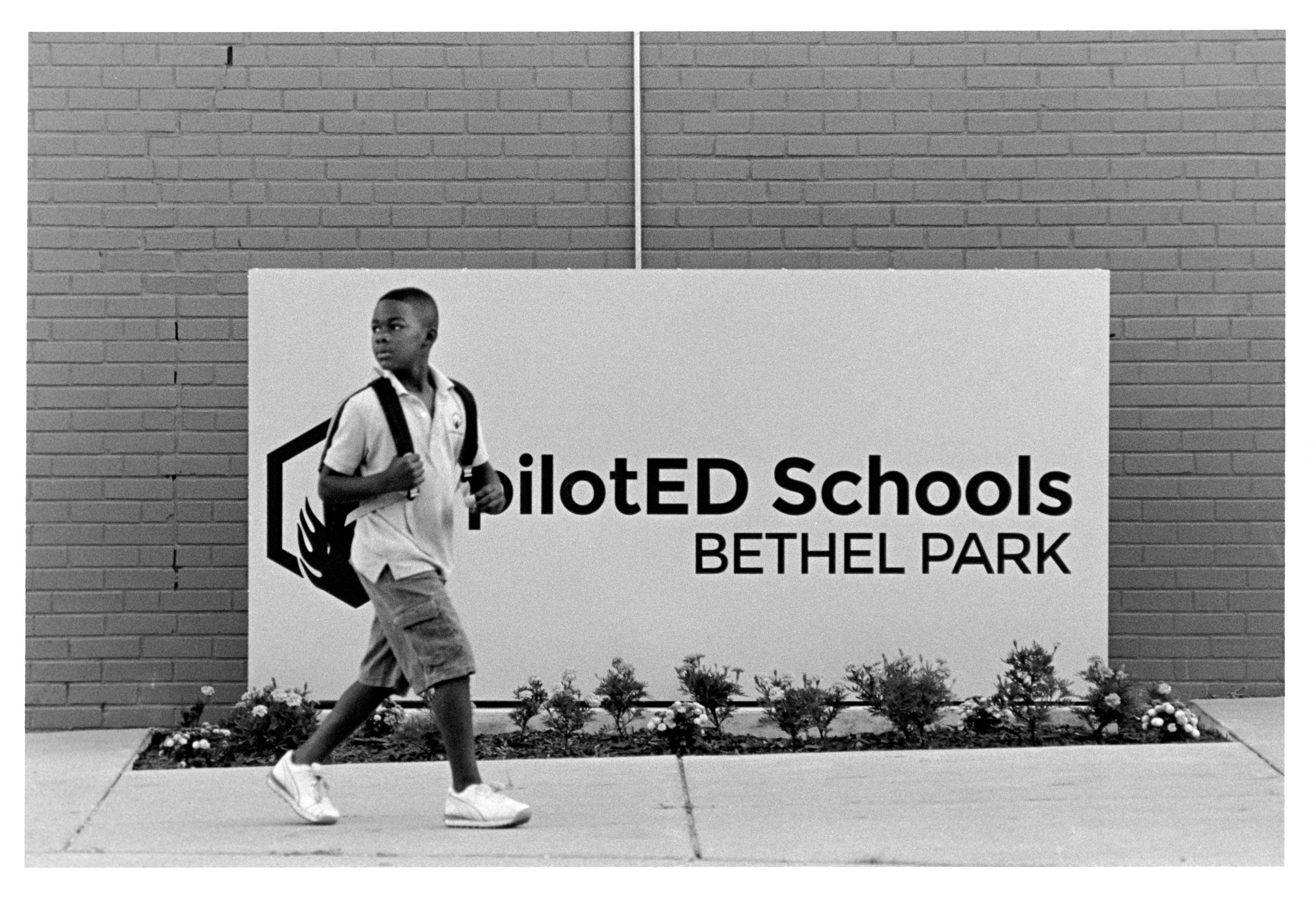

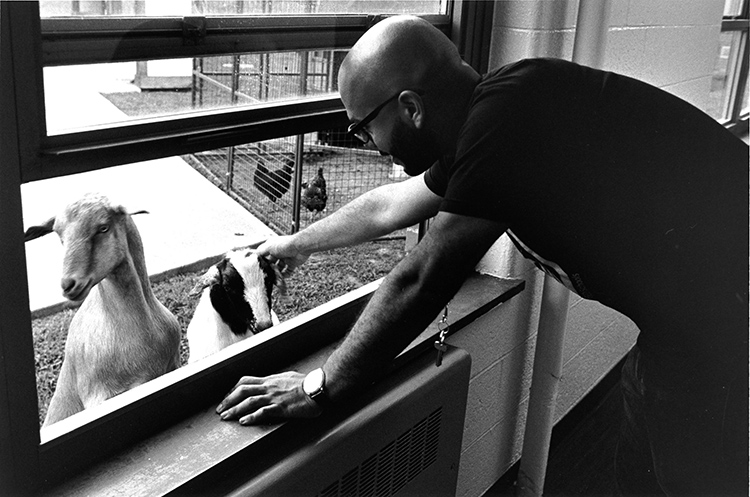

PilotED Bethel Park, a new charter school launched by UW Bothell alumnus Jacob Allen (pictured at top with young Jax) and his co-founder Marie Dandie, operates on Indianapolis’ south side, in a low-slung 1950s-era building set between a Section 8 housing complex and a sprawling cemetery. The school’s students are mostly black and Latino, but many residents in the neighborhood are white descendants of the Appalachian migration. Visitors can spot a Confederate flag or two while driving down the area’s wide streets past small, worn-but-neatly kept homes.

According to Opportunity Atlas, a tool that estimates social mobility by census tract, the average future income of a child growing up in the neighborhood around pilotED is $21,000 a year. Ten percent of children from the neighborhood might expect to be incarcerated; that percentage jumps to 14 for black children. This is a struggling neighborhood in a city where the gulf between have and have-not is gaping and climbing out of poverty is particularly tough. Indianapolis ranks 46th among the nation’s top 50 metro areas in terms of upward mobility. If you are born poor here, you are very likely to remain that way.

But pilotED and the people who work there belie those dire predictions. The school is an oasis—a warm and welcoming space with a young, energetic staff, brightly painted walls, an urban farm and a lovable miniature pinscher named Winston. Children are greeted in the morning with positive affirmations, and classroom conversations are dedicated to students and their experiences—new baby sisters or final immigration papers. PilotED does not suspend students or send them home, preferring instead trauma-informed and restorative justice practices. Students are evaluated based on “satisfactory participation,” not A-through-F grades. The school’s curriculum is centered around academic excellence, civic engagement and social identity training. This last piece—the focus on identity—may just be transformative in the educational landscape, particularly for students of color, including African American students.

Martavius takes a look back at his mother after she drops him off in front of the pilotED School.

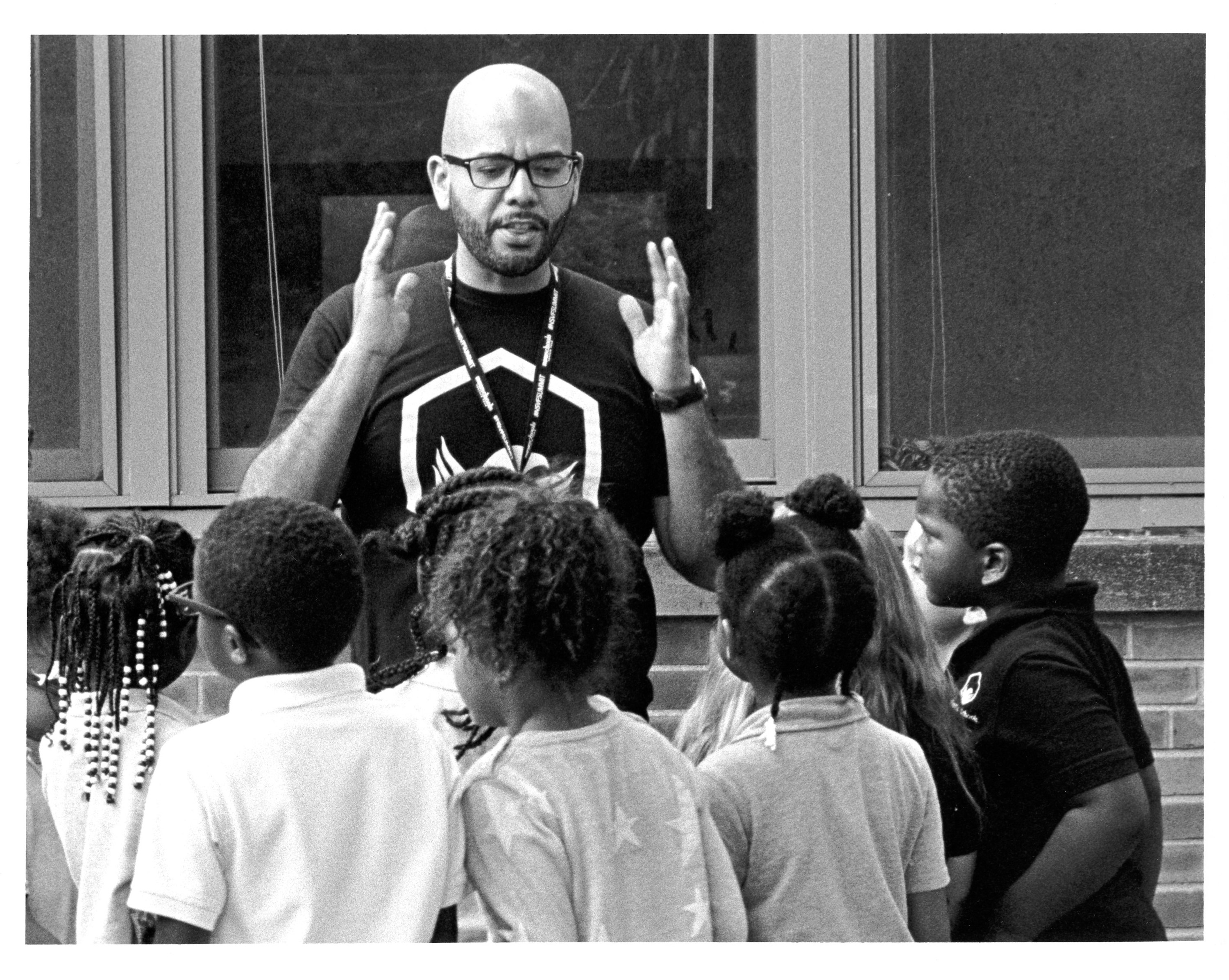

Jacob Allen thanks pilotED students for their help weeding and cleaning litter outside the school.

For centuries, black people have believed in the power of education to transform their lives. Yet black students receive lower grades and test scores, are more likely to quit school and less likely to graduate from college. And that gap persists across class and circumstance. If education is a “passport to the future,” as activist Malcolm X once claimed, then the future for black America looks bleak.

Many academics, experts, politicians and pundits have tried to grasp the reason for this achievement gap between black students and their white counterparts—often conveniently placing the blame on dysfunction in black families, neighborhoods or culture. But noted Stanford social psychologist Claude M. Steele suggests that there is a “vastly underappreciated” connection between the “endemic devaluation” of blackness and academic achievement.

Many black children spend their educational careers learning only what long-dead white men have contributed to the nation. Their hair and bodies are deemed illicit by supposedly unbiased dress codes. They are viewed with suspicion and disciplined more severely than other students. And scant attention is paid to the ways systemic inequality may affect their ability to sit quietly, reading, writing and doing arithmetic.

Schools have been ill-equipped and unwilling to reckon with blackness and also with the effect of oppression on black lives. Homicide is the leading cause of death for African American youth ages 15 to 24. Sixty percent of black girls have experienced sexual assault by the age of 18. And more than 61 percent of black American children have had at least one adverse childhood experience, a traumatic event associated with negative outcomes in learning and development.

“We are teaching radical ideology in the classroom. What I learned my senior year in college is being brought down to kindergarten. How does a 5-year-old grapple with race, gender, sexuality, religion?”

Jacob Allen, founder of PilotED Bethel Park

“Biases and racism are alive and well in K-12 public education,” Allen, ’12, says. “We shouldn’t be surprised that mental hospitals, prisons, low-income jobs are being filled by a certain type of person … a person that is black or brown … a person who attends all of our K-through-12 public education in urban America.”

Allen confirms that this is not a criticism of the many caring, committed educators and administrators who have worked to teach and support black students; it is a rebuke of a system that increasingly fails marginalized young people. He witnessed this failure up close as a teacher on Chicago’s West Side, and as a student growing up in Los Angeles and then suburban Wisconsin. Allen earned his bachelor’s degree in Society, Ethics, and Human Behavior from UW Bothell a few years ago and is also a graduate of the Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management’s executive program for nonprofit management. But he is the only one of four brothers and 62 first cousins to “work the system, get the scholarships, fight depression [and] forget about dropping out.”

“There’s a million other Jacobs. The world’s an unfair place, and if we don’t give our kids the emotional, the academic, the cultural tools to not only maybe game the system, but to make the system more fair, then I’m just a blip on the radar.”

Allen has made it his life’s work to change the often-broken way we educate students, especially the most vulnerable ones.

Azarean and Principal Marie Dandie dare each other to eat one of the mealworms used to feed a frog kept in the office of Jacob Allen. Azarean was one of the students who got to feed the frog as a reward for doing well in the classroom that day.

Five years ago, Allen and Dandie, then an English teacher on the South Side of Chicago, developed a unique curriculum rooted in sociology and identity exploration. Their approach allowed time to acknowledge their students’ unique identities and, in an age-appropriate way, to discuss human commonality and difference. When they introduced that curriculum in their classrooms, adding a little time each day for self-exploration and social and emotional learning, student performance improved.

“My students outperformed everybody,” Dandie says enthusiastically. “Once you acknowledge who the child is as a human being … what comes after that are highly engaged students. You’ve acknowledged their human self, you’ve validated all of their emotions, their anger, their sadness, their happiness. They understand. Now they can be even more engaged because they have the vocabulary to name the things that happen in them. When they meet characters in their books, they can connect more. They can answer comprehension questions because they’ve been forced to think about themselves and now they’re making those connections with the book.

“[To meet academic standards] you have to be able to think critically, and if our kids don’t even know how to navigate their own bodies or communities, there’s no way they are going to be able to critically think about Anne Frank and what she went through.”

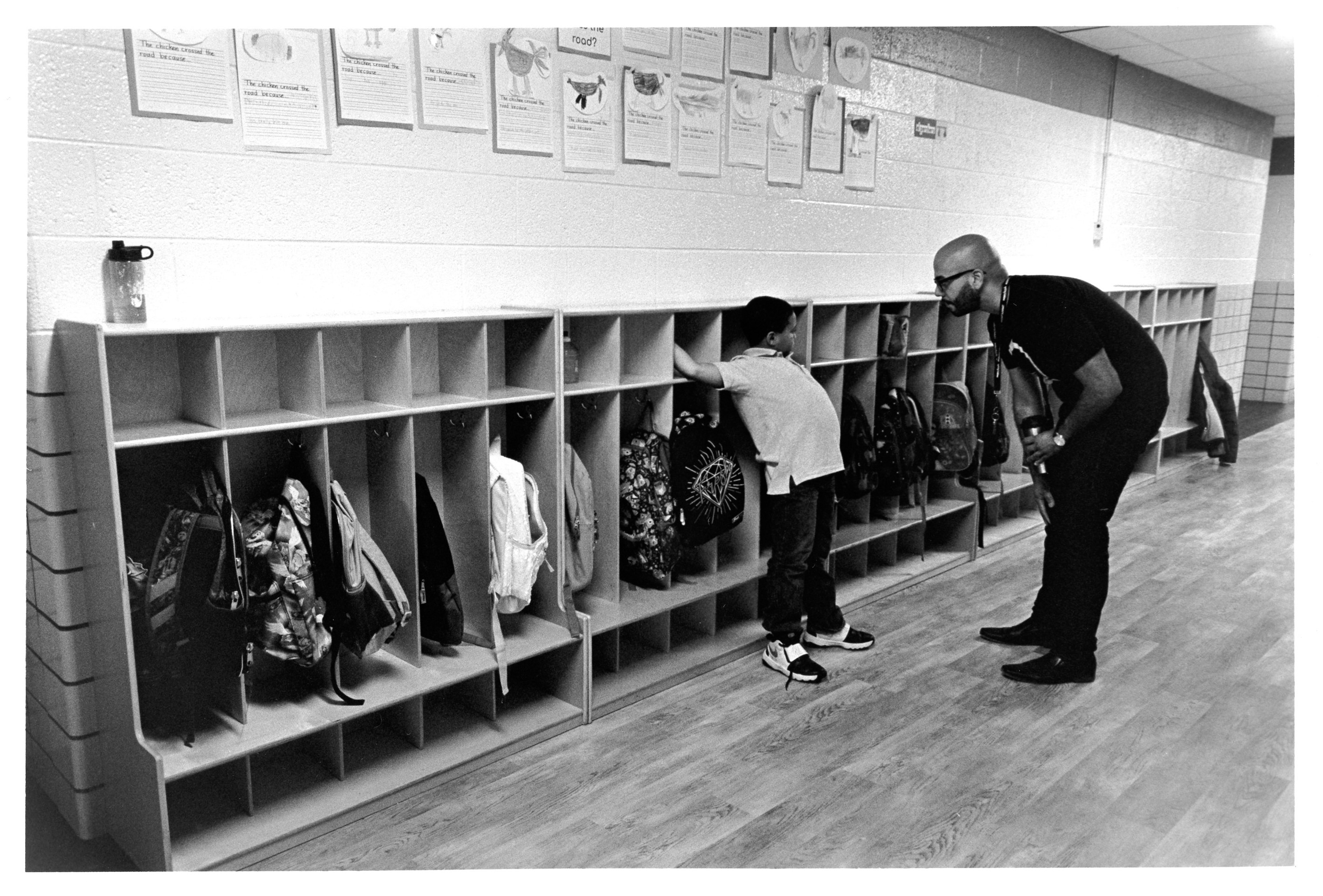

In a quiet and calm voice, Jacob Allen explains to Jax why he needs to change his behavior.

Allen, who experienced a system of biases and racism growing up in big-city America, aims to set a new system in place to give children of a color a chance to become a success.

On Aug. 6, 2018, Allen and Dandie opened the doors of their first charter school, pilotED Bethel Park. The school serves 94 students in grades K-2. Allen serves as CEO, while Dandie, a graduate of Central Michigan University and Northwestern University, is the principal. The pair chose Indianapolis because of the city’s support of school innovation and its deeply engaged community.

“Three weeks per month we were in Indy,” Allen says. “Marie and I bought an Airbnb, and then just started canvassing in the neighborhoods. We started realizing education is at the tip of [everyone’s] tongues here. People said, ‘If you open a school [like this] in my neighborhood, can I be on the PTA? Can I drive the school bus? Can I be a lunch lady? Can I teach?’”

Five educators followed Allen and Dandie from Chicago to be a part of their work. Ten more relocated from other states. The curriculum is energizing. There is an Identity Class taught every day at the school. Students discuss things like melanin and chromosomes, the history of beauty in America and discriminatory practices toward kids of color. They mix paint colors to mimic their skin tones and give the colors names like “crumbled cookie” and “cinnamon.”

“We are teaching radical ideology in the classroom,” Allen says. “I mean, this is essentially … what I learned my senior year in college is being brought down to kindergarten. How does a 5-year-old grapple with race, gender, sexuality, religion?”

Today, Mr. Laster introduces vocabulary words—ordinary, extraordinary and unique—that the class of wiggly second-graders repeat. Then the class reads and discusses R.J. Palacio’s book “We’re All Wonders” that encourages children to embrace difference.

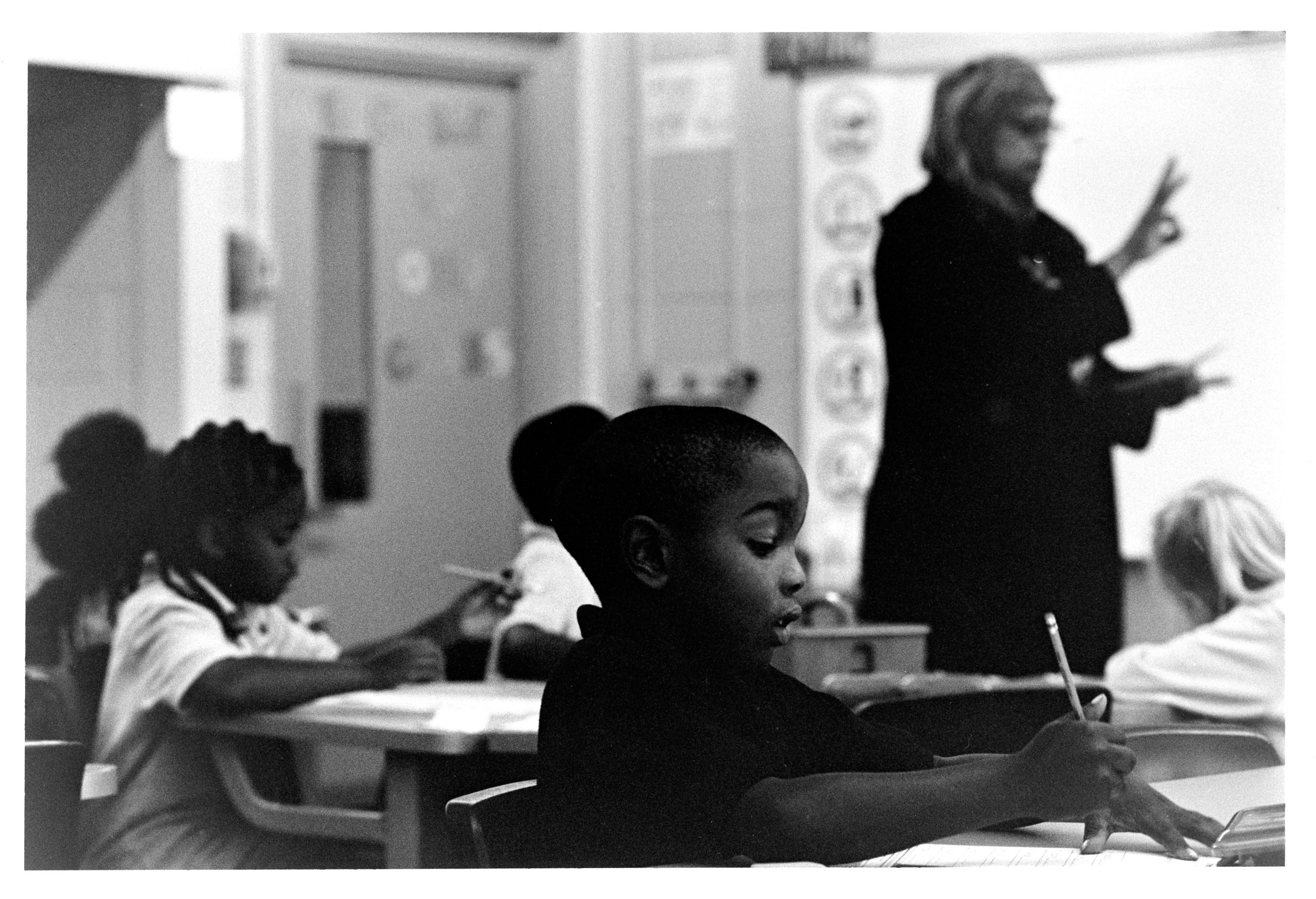

Tayvion and his classmates work on their math problems as their teacher Bonnie Lovelace explains the lesson.

An outdoor farm is one of the innovative features the school offers to children.

“But some people don’t see that I’m a wonder. All they see is how different I look. Some people don’t see that I’m a wonder. They don’t see that I’m unique. They only see how different I look. Sometimes they stare at me. There are 35-year-olds who cannot have these discussions,” Allen tells me proudly. An acknowledgment of identity doesn’t simply happen in this classroom; it is baked into the ethos of the school. For school administrators, Allen and Dandie are uniquely present in the lives of their students, invested in their positive self-regard.

Dandie, a petite, energetic woman fond of headwraps and natural hairstyles like Afros and twists, recounts how, earlier in the year, a biracial student with big, beautiful curls drew a picture of herself with stick straight hair. “I don’t like my big hair,” the student said. The principal not only discussed the beauty of all hair textures with the girl, but also arranged with the Spanish teacher for both educators to wear their hair curly for the next two weeks. Now, the student proudly wears her curls.

PilotED Bethel Park will add a new grade each year up to the 8th grade, but Allen and Dandie are invested in reaching many more children than can walk through the doors of their school. They are working on a national curriculum. Allen says, “Our pie-in-the-sky goal is to get a curriculum published that is then pushed through the K-12 education system [like Common Core] at the state level, including in places like Washington [state]. Because what are we going to do when they become middle-schoolers and they know the world better than the world knows them?”

In the meantime, Allen says, “We are creating what we think is part of the solution, which is getting kids the tools, making sure they have the vocabulary to go off and slay it in a way that is—yes, heavy on science, mathematics, and English—but is also heavy on a sense of self, a sense of community, a sense of history.”

He and Dandie are in this work for the long haul.

“I’m doing this for the rest of my life, because I have to … There’s this weird fire in me, fueled by … I don’t know if you want to call it God, reality, today, yesterday … It’s just alive and it’s not going anywhere.”

Identity Teacher Maddox Cory takes students across Bethel Park, which is next to the school, for recess.