To look at George Nakashima's furniture, one would expect it to be the work of an introspective man who has led a life of contemplation. There is such a great appreciation of the material—fine hardwood—and an obvious investment of time in each piece. They are the very antithesis of the stress-ridden, mass-production ethos of the late 20th century.

Yet Nakashima, the 1990 University of Washington Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, has led anything but a quiet life. Born in Spokane in 1905, he worked on building the railroads through the Cascades and at salmon canneries in Alaska. He studied at the UW, graduating with a degree in architecture in 1929, and continued his studies at MIT and Fontainebleau in France. He spent a year in Paris during the heyday of the 1930s, and also spent about four years in Japan. Central to his life—and his art—were the two years he spent at an ashram in India, where he designed and built one of his greatest works and became a disciple of Hindu philosopher Sri Aurobindo.

Fifty years later, tracing the influences of his art, Nakashima says, “Living in the Northwest helped me develop the relationship between art and material,” his love of fine wood and his ability to see the beauty waiting to be released beneath the bark. When asked if his art was more influenced by America or Japan, he responds, “I would think it’s kind of a combination. I now belong to the world.”

Just before war broke out between Japan and the United States, Nakashima returned to Seattle and began a furniture workshop. But shortly after Pearl Harbor, he and his family were sent to an internment camp in Idaho. “When we were put into internment camps in 1942, our daughter was six weeks old and it was very difficult,” he comments. “I felt that the whole thing was very stupid, but out of this experience came some good. There was a very fine Japanese carpenter who became my instructor while I was the designer. He was a great influence on me,” the artist recalls.

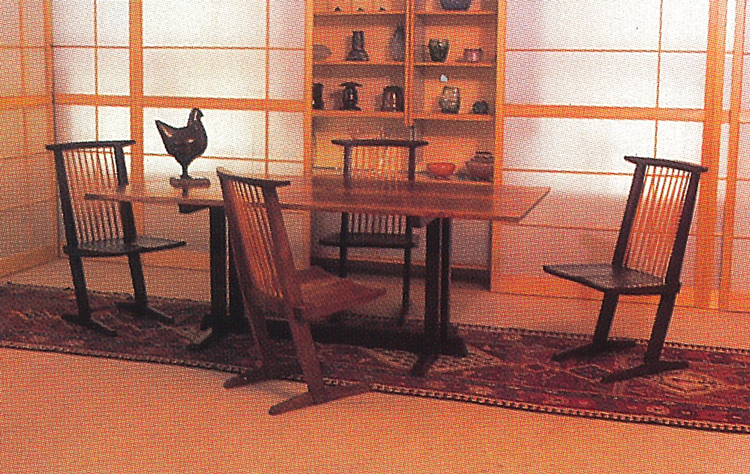

Nakashima furniture courtesy of Anne Gould Hauberg, UW Class of 1939. Photos by Mary Levin.

In the later stages of the war, Nakashima and his family moved to New Hope, Penn., to start a new life as furniture artisans. In the post-war era of chrome and Formica, Nakashima’s beautiful woodwork was unique. Commissions began to trickle in, and articles appeared in House Beautiful, Life, Look, Harper’s and other magazines.

Today Nakashima stands as one of the finest American artists working in wood. Greatly admired in Japan and Europe as well as his home country, he was commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to produce a room for its new Japanese Wing. He also designed and built all the furniture in Nelson Rockefeller’s Tarrytown, N.Y., home.

His works include the architecture and furnishings of several Christian churches in Japan; the disciple’s residence and furnishings at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, India; and most recently the three-quarter-ton Altar of Peace at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.

Though he has traveled far, the UW graduate has fond memories of his alma mater. “When I first entered (the UW), I was in the forestry department. After I transferred to the architecture department, I felt I found my place to develop my creative talent,” he recalls.

Asked what professors he found most influential, he immediately cites Carl Gould. “He, to my mind, represented the best in the teaching profession,” he explains.

The 85-year-old Nakashima has been in poor health, having suffered a stroke in October, but he plans to attend the commencement ceremonies held June 9. And the Nakashima legacy at the UW may continue this fall with the arrival of his grandson, who has been admitted to the UW Class of 1995.

Excerpted from The Soul of a Tree by George Nakashima. © 1981 by Kodansha International Ltd.

“My life has been a long search across the tumbling screes on mountain slopes around the world to find small points of glowing truth.”

“Backed into a soulless steel and glass jungle which threatens the disintegration of our systems and institutions, we face an unknown future. With a prodigious drive we have built the first true megalopolis, but we have produced so little of any intrinsic value. There is not a single monument in recent centuries to express any sort of transcending human will or soul. Taken as a whole, we have the poorest assemblage of architecture in the history of man, without a single building of greatness.”

“We are on the verge of a great and heroic revolution, a revolution of the soul—a revolution so vast and influential that the revolutions of the West, the French, the American and the Russian, will appear childish and impotent. The transformations stretch out into endless vistas before us.”

“It is sad that when some movements arrive their time is already past. Such is the case with ‘modern’ art. ‘Modern’ architecture was interesting and exciting in the thirties, but by the eighties structures have become filled with dead forms. The new buildings do not have the staying power and catholicity of architecture during the truly great periods.”

“Since I am a woodworker, the practical aspects interest me primarily. The materials used, the utility of an object, the forms developed are vital. The necessary skills and the resultant beauty must be there. Arts and crafts should be based on pure truth, taking materials and techniques from the past to synthesize with the present. We should be content to work on a small scale and integrally with nature and not violate it.”