With Miss Peoples in their corner With Miss Peoples in their corner With Miss Peoples in their corner

Gertrude Peoples, a beloved student adviser and advocate, reflects on her time at the UW

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos by April Hong | Viewpoint Magazine

Late this summer, Gertrude Peoples visited the Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center and sat down to reflect on her 41 years helping students and student athletes navigate through college. Now in her 90s and dressed in a stylish track suit, Peoples looked around the student-focused center and remarked how much had changed from the time she was recruited to work in the Office of Minority Affairs in 1970, right at the start of the UW’s Educational Opportunity Program.

“Sam Kelly saw something there that I surely didn’t see in myself,” she says. Samuel Kelly, who was hired as the UW’s first vice president for minority affairs, knew Peoples through her family: Her younger siblings, Dan and Verlaine Keith, were founding members of the UW’s Black Student Union. He asked Peoples to join his office and support newly recruited students of color in the Educational Opportunity Program as they figured out how to navigate college.

“That was the genius of the man,” Peoples says. “He did know it would be difficult and a lot of students weren’t prepared by their high schools,” so he created a sophisticated program of welcome and support. Peoples took on a group of African American students and worked closely with them, deciphering the course catalog and registering for classes. She advocated for them with their instructors.

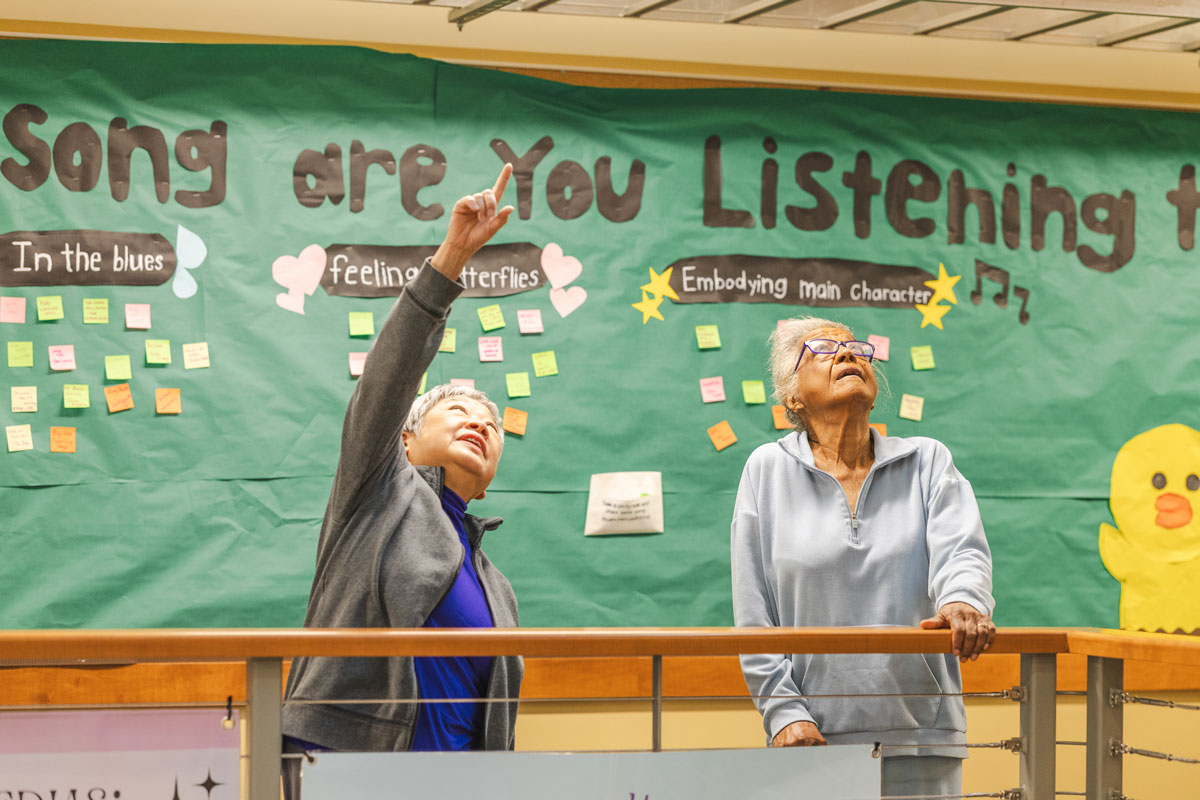

Sharon Maeda, ’68, a former director of the Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center, points out the original student-created murals from the 1960s and ’70s.

Peoples’ students were so successful that other parts of campus took notice, and one of the coaches started sending athletes to her for help. Within a few years, she was hired away from the Office of Minority Affairs by the Athletics Department, which had been grappling with a reputation for treating Black athletes unfairly.

As the coordinator (and later director) of Athlete Services, Peoples not only became a valuable resource for men and women on many different sports teams, she was a secret weapon for the recruiters—traveling to high schoolers’ homes and talking to

parents, “letting them know their kid would not be lost in the abyss,” she says.

The students all called her “Miss Peoples” and relied on her for everything from housing advice and study tips to help choosing a major.

“Miss Peoples was always at her desk when I saw her,” says Lincoln Kennedy, ’94, the offensive tackle who, after an illustrious Husky career went on to play 11 years in the NFL. “She was very inviting and warm, but you know she meant business when she talked to you.” While so many people focused on his success as an athlete, Peoples was dedicated to ensuring that he and the other athletes thrived in school. “She was a mother to us students away from home,” he says.

For one basketball player, Peoples’ support extended into the delivery room. The former Husky athlete recently shared a picture of her son, “and he’s over 40 now!” Peoples says with a laugh.

The athletics program quickly recognized what an asset she was, and word of her work spread through major universities across the U.S. A multi-page feature story in Ebony magazine in 1975 celebrated Peoples as one of the only woman recruiters in college sports. As the article explained, families felt assured by Peoples’ presence on campus. The athletes themselves said they felt safe with her—that they had a person to share their concerns with, including the pressures and mental-health struggles that often come with being a student-athlete.

“She was very inviting and warm, but you know she meant business when she talked to you.”

Lincoln Kennedy, former NFL player, unanimous All-American and Rose Bowl Hall of Famer

“I helped them with course selections and discipline. And we had a study table,” she says. “I made trips around campus to talk to certain professors and see if they would be kind to the students if they had issues with attendance.” She went to practices and frequently traveled with the football and basketball teams.

The list of Husky footballers she worked with includes Lincoln Kennedy, Stafford Mays and Bruce Harrell—Seattle’s current mayor. “I knew him when he was born,” Peoples says. And Spider Gaines. “He was from Oakland, and so full of himself,” Peoples says. “And he got into trouble his senior year.” Gaines, one of the greatest wide receivers in Husky football history, struggled with substance abuse, injury and a rocky few decades before returning to the UW to finish his sociology degree in 2006. “He called me one morning and said, ‘Miss Peoples, can I come and talk to you,’ ” she says, explaining that Gaines returned to school decades after leaving, finished his degree “and changed his life. He was the farthest out there and he came back in.”

Peoples’ student-athletes will surely remember the sound of her heels clacking on the bricks and tiles as she tracked them down across campus. “Some professor would call and say someone just missed an exam, and I would try to locate them,” Peoples says. “A lot of our kids would hang out in the HUB. I knew exactly where they were.”

She also welcomed them to her home over breaks and holidays, so much so that her grandson started calling her “Miss Peoples.” She loved the students, and they returned her devotion. “They needed a mom on campus,” says Sharon Maeda, a student adviser in the 1970s and director of the Ethnic Cultural Center from 1973 to 1975. “I can visualize a meeting going on and Gertrude walking into the back of a room and all the athletes turning around.”

Peoples relished seeing her students graduate, and she misses the excitement of working in college sports. To her delight, many stay in touch through messages and letters. Nowadays she plays bridge and keeps up with her family but doesn’t often venture from home. She was glad to come back to campus for a visit.

“The UW is now getting so many different kinds of students and so much effort is focused on inclusion,” she says. “I am overwhelmed by what it is today.”