Editor’s note: The following is a letter written by Margarethe “Grethe” Cammermeyer, ’76, ’91, who served as an Army nurse in Germany, the US and Vietnam. She is widely known as a gay rights activist, and her story is memorialized in her autobiography “Serving in Silence” and a film of the same name. She traveled with an intergenerational veterans on a PeaceTrees Vietnam trip in 2019.

We spent 2–3 days in North Vietnam having a chance to listen to North Vietnamese veterans, including fighter pilots who boasted of shooting down our aircrafts and pilots. Others boasted of having our soldiers as prisoners of war. It was tough to reconcile that we were here in peace and yet they were boasting of their heroics during war. It caused some angst because we, too, were reliving emotions of the war. Here we were seeking reconciliation and yet were still intruders in their land.

We continued driving South from Hanoi, seeing hundreds of thousands of monuments throughout the countryside to those who had been killed. At their national cemeteries were row after row after row of those who had died. I reflected on our own National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. with precision positioned headstones of servicemembers remembered for having died in wars. And we have our Vietnam Wall paying tribute to those who died in the Vietnam conflict. There was a difference in Vietnam though. The monuments were everywhere, including the indentations in the land where American bombs were dropped. There were still the tunnels where families and communities had to bunker down to survive and which continued to be a stark reminder of our unrelenting bombing. Observing now, even 50 years later, the Vietnamese landscape gave pause and a sense of shame of the horror we had inflicted upon the Vietnamese people.

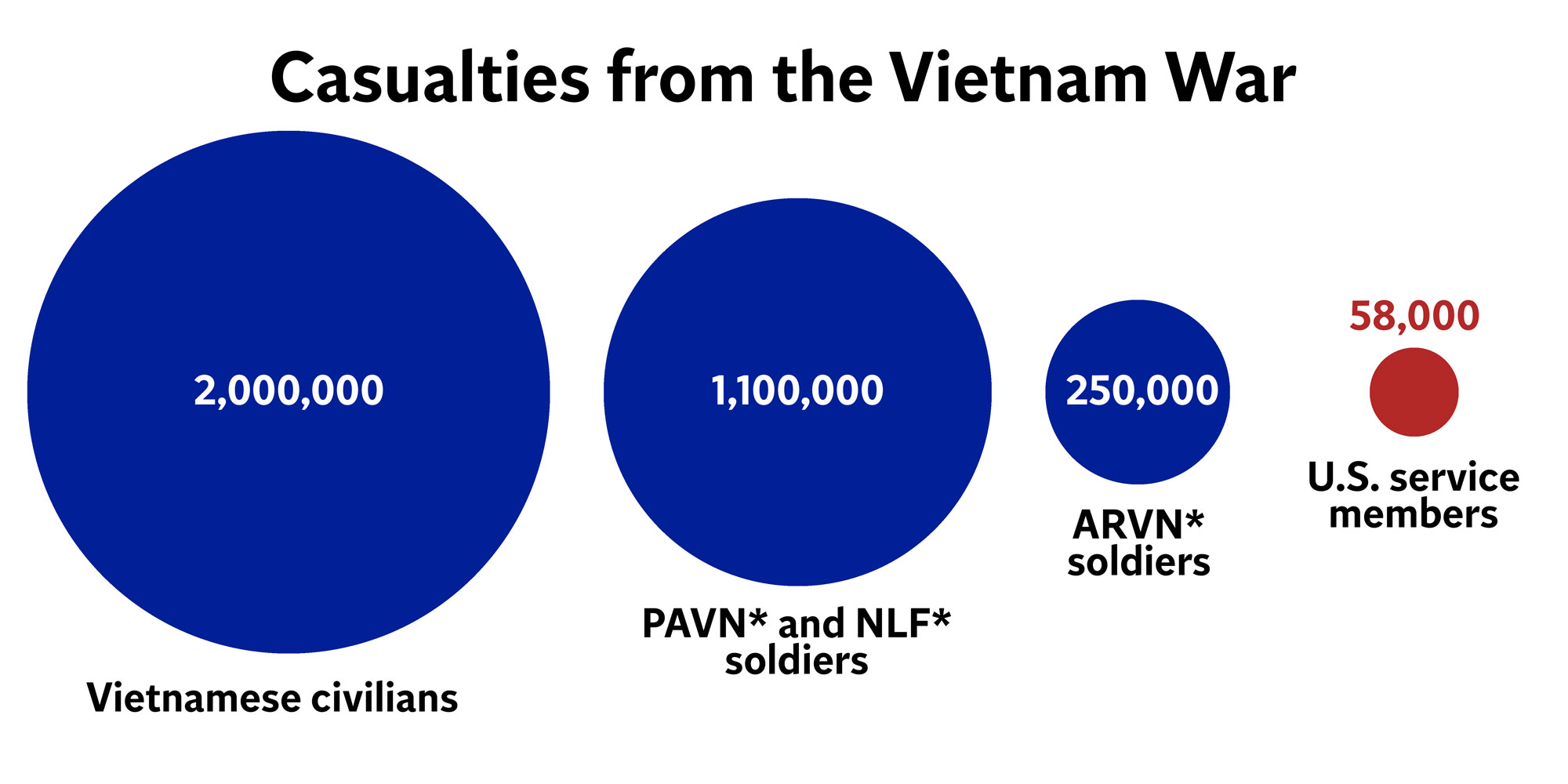

*PAVN, NLF and ARVN stand for People’s Army of Vietnam, National Liberation Front and Army of the Republic of Vietnam, respectively.

Now reflecting on American involvement in Vietnam became similar to the Nazi’s invading and occupying Norway during WWII. I was very conflicted since I had believed we had participated in the war for noble reasons but had to reconcile we were the invaders. The more I learned about our involvement in Vietnam, the more sympathetic I felt toward the Vietnamese. As these thoughts dwelt in my mind, I understood the importance of this trip back to Vietnam for healing.

Our travels took us to Hue, where the Tet Offensive of 1968 reached a peak. Larry, one of the VN veterans in our group, actually fought in the battle of Hue. We walked the walk with him, crossing the bridge where he and his platoon had approached the wall surrounding Hue, where his commander stopped their advance fearing a trap where they would all have been killed. He told us of his comrades and pointed out where each had been killed. We felt like we were transported back 50 years and were there with him. We then proceeded back to a church which was still standing from the war. Larry solemnly read the names and ages of each of his comrades who had died that day. We all were filled with grief, reliving his and our experiences of the times. Visiting Hue with Larry brought back all that was horrible of our experiences of war and the memories we had carried for so many years.

The monuments covered the countryside as the continuous reminder of death, destruction and the past. How can you ever move on when you are essentially living in a cemetery? It was certainly the reminder of what we, the Americans had perpetuated on the Vietnamese people. We lost 58,000 and they lost hundreds of thousands of souls.

It took some time to regroup on this trip to remember why we had returned to Vietnam in peace and reconciliation. Certainly it reinforced the importance of PeaceTrees Vietnam and their de-mining efforts and bringing former enemies face to face.

Several of us had the extraordinary experience of meeting a North Vietnamese nurse who had first served in the North Vietnamese Army and later became a Vietnamese Army Nurse. She and her husband (a surgeon) provided care for the wounded, including Americans, in the tunnels where they lived and worked. The tunnels had been built to withstand American bombardment, so they were up to 100 feet underground. The nurse told of living, having a family and working in these tunnels for years. Despite the hardships she and her family survived, though her husband ultimately died from complications of Agent Orange exposure. She bore no grudge and was warm, gracious and welcoming during our time together. As we left she commented that we should do this more often, helping former enemies become friends.

COL Grethe Cammermeyer, ret.

UW: MA 1976; PhD 1991

18 Mar 2022