Her life’s work: solving the evolution of art Her life’s work: solving the evolution of art Her life’s work: solving the evolution of art

By Bruce Barcott | Lead photo by Mel Curtis | March 2009 issue

As a young woman in the 1950s, Ellen Dissanayake worked as a secretary to put her husband through graduate school. She stayed up late typing his papers. She circulated at faculty parties. She trained for that peculiarly-midcentury career, faculty wife.

Her husband, John Eisenberg, was studying for a Ph.D. in zoology at the University of California at Berkeley. Eisenberg would later become head of research at Washington, D.C.’s National Zoo, but back then he was just a grad student looking into animal behavior. “Everyone around us was talking about aggression, sex and territoriality in animals,” recalls Dissanayake (pronounced diss-an-eye-akuh). “And you couldn’t help thinking, Hey, we’re animals too — how much of this applies to us?”

At the time, applying Darwinian impulses to human behavior was a concept too untested for general consumption. “This was years before Desmond Morris published The Naked Ape” — the groundbreaking 1967 book that looked at humans as an ape-like species that evolved to survive as hunter-gatherers — ”and no one articulated these things publicly,” says Dissanayake. “But we talked about them amongst ourselves.”

Those discussions inspired an even more radical idea, one that Dissanayake kept to herself for years. As an accomplished musician with a master’s degree in art history, she wondered about the role of art in human evolution. Why did people make it? What evolutionary purpose did it serve? Did art evolve?

Nearly a half-century after she began asking those questions, Dissanayake, an affiliate professor in the University of Washington’s School of Music, is still trying to answer them. But now she speaks as a global authority. Her three books, What Is Art For?, Homo Aestheticus and Art and Intimacy, all published by the University of Washington Press, are considered foundational texts in the field of evolutionary aesthetics. Long before interdisciplinary studies became trendy, Dissanayake synthesized art history, anthropology, psychology and ethology to come up with a paradigm-changing theory: Art-making evolved as a behavior that contained advantages for human survival — and those advantages went far beyond what Charles Darwin ever imagined.

“There are a number of us attempting to mount a Darwinian analysis of art and the aesthetic response, but Ellen originated it,” says Denis Dutton, author of the new book The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. “The freshness of her thinking is sometimes astonishing.” The eminent biologist E.O. Wilson has hailed her as “a true pioneer.” Harvard linguist Steven Pinker wrestled with her theories in a chapter of his best-seller The Blank Slate. Martin Skov, editor of Neuroaesthetics, a new anthology in the emerging field that explores the biological roots of aesthetic experience, calls Dissanayake “the doyenne of adaptationist aesthetic studies.”

What makes her story all the more remarkable is that she laid the cornerstone in a new field of scientific study without the usual imprimaturs of academe. She has no tenure or permanent appointment. She doesn’t even have a Ph.D. Ellen Dissanayake is a self-taught scholar in a field she invented, working to solve a riddle that runs past Darwin to the very beginnings of human civilization.

***

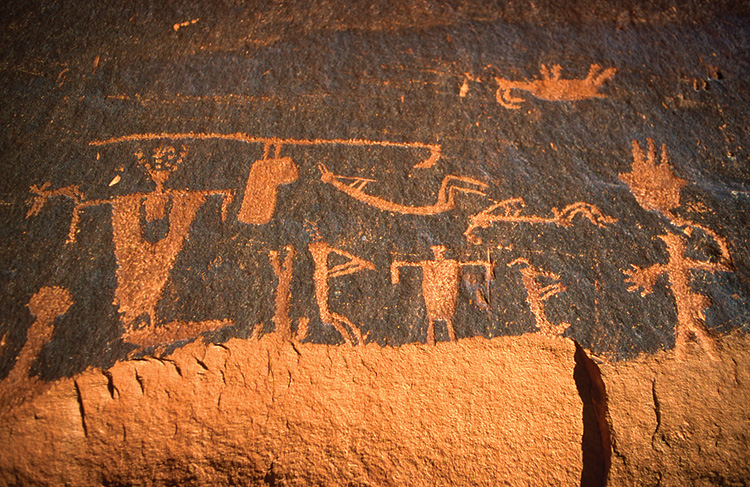

Petroglyphs from a site in central Arizona, approx. A.D. 700–1300.Ekkehart Malotki

When I offer to meet Dissanayake at the Seattle Art Museum — an appropriate place to chat, I had thought — she dismisses the idea. “My work isn't really about asking what's good art and what's bad art,” she says. “In fact it's not really about contemporary art at all.”

We settle on the cafe at the Burke Museum — a more apt setting for one fascinated with the activities of early Homo sapiens. Besides, she says, the stuff on the walls at SAM and the Henry Art Gallery is beside the point. “The arts of our time aren’t the things hanging in the ‘high art’ galleries,” Dissanayake tells me. “The arts of our time are advertising, blockbuster movies and participatory rituals like the Super Bowl or the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games.”

Critics and admirers have described her ideas as audacious, startling and brave. Yet to meet Dissanayake in person is to encounter a fierce intellect cloaked in modesty. Now in her seventies, she dresses in quiet but well-made attire, like a woman on her way to a chamber music concert. Her face peeks out from behind a parted curtain of brown bobbed hair. She drinks tea, lives frugally and favors public transportation. Her demeanor bespeaks mildness. But when it comes to the battle of ideas, she’s anything but mild. “My work and my biography are very intertwined,” she says, and over the course of an afternoon Dissanayake sketches the evolution of her life and her ideas.

The autodidact’s road is often circuitous, but Dissanayake’s meandered to the far corners of the globe. During the 1960s she and her first husband, Eisenberg, lived in Washington, D.C. He worked at the National Zoo while she earned a master’s degree in art history from the University of Maryland and raised two young children. Trips to Madagascar and Sri Lanka — for Eisenberg’s fieldwork — piqued Dissanayake’s interest in the connection between art and play.

At the time, work in the field of aesthetics and evolution hadn’t progressed from Darwin’s so-called peacock principle. In The Descent of Man, Darwin suggested that beauty was an element of sexual selection. The peacock’s tail, a heavy burden to drag around (especially when eluding predators), had no survival advantage, so Darwin believed it existed as a sexual enticement.

Dissanayake considered Darwin’s peacock principle and thought, ‘That can’t be the only reason for art.’ “Humans are naturally aesthetic,” she says. “You find art-making in every culture. It’s a genetically predisposed activity, much like language. To say that its sole reason is to confer advantage in sexual selection is far too limiting.”

While she was in Sri Lanka, life threw her a curve. She fell in love with a local doctor and medical professor, S.B. Dissanayake. After returning to Washington, D.C., she made an extraordinary and privately agonizing decision to leave Eisenberg, return to Sri Lanka and marry Dissanayake. Her children, 7 and 9 at the time, remained in the U.S. with their father, a situation Dissanayake once described as “the one regret in my life.”

“I left one life,” she told me, “and jumped to another.”

***

Painted panel, central Sahara Desert, Algeria, approximately 4000-2000 B.C.Ekkehart Malotki

For the next decade and a half, Sri Lanka proved to be a perfect crucible for her work. She lived in the old colonial capital of Kandy, where her second husband taught at the University of Peradeniya. Every summer she returned to Washington, D.C., to spend time with her children and conduct research in the Library of Congress. In Kandy, she immersed herself in the arts of Sri Lanka and enjoyed inside access to the country's ancient customs.

“I ended up going to a number of weddings and funerals,” she says, “and occasionally to less common rituals like exorcisms and sing-sings, which are singing competitions. I felt very much like I belonged to Sri Lankan society. Most of our friends were Sri Lankan, and my husband had grown up in a feudal kind of village.” Those Sri Lankan weddings and funerals, she says “made me aware that ceremonies are collections of arts. Subtract the chant, music, masks, dance, painting, and you’re left with nothing. It made me realize that art probably evolved from ceremonies.”

To follow that idea, though, she first had to answer a fundamental question: What is art?

At the time — the late 1960s — art was still defined mostly in terms of objects, beauty and the experience of the viewer, reader or listener. Dissanayake’s great insight was to grab it by the other end of the stick, considering not the viewer but the creator. She defined art as a behavior and came up with a two-word phrase that captured the activity in its broadest permutations: “Making special.”

“We don’t have a verb, ‘to art,’ but what are artists, dancers, poets doing?” she says. “They’re taking the ordinary and making it special. You create a bowl out of mud but you don’t leave it ordinary, you make it special by engraving a pattern or figures on it. A poet takes ordinary words and makes them special. An artist places an activity or an artifact in a realm different from the everyday.”

What she says may sound obvious, but Dissanayake’s new paradigm of art exploded the conventional wisdom that held the cave paintings at Lascaux (ca. 15,000 B.C.) as humanity’s earliest known artistic creations. Her “making special” definition simultaneously disconnected art-making from Darwin’s notion of beauty and pushed the emergence of human art back tens of thousands of years to the earliest known evidence of body marking.

The next step was to figure out why humans created art — to identify its evolutionary advantage. Working in Sri Lanka, Dissanayake pored over books on anthropology, psychology and art history in the University of Peradeniya’s limited library. She traveled to Papua New Guinea and Nigeria to observe rituals in the South Pacific and Africa. What she saw there sparked her next breakthrough.

“Ceremonies occur at a time of transition between states,” she says. “Birth, marriage, wartime, sickness, death — these are moments of great uncertainty and anxiety.” In those moments we desire the power to rein in the chaos. Making art, Dissanayake wrote in Homo Aestheticus, gives us “the ability to shape and thereby exert some measure of control over the untidy material of everyday life.”

She’s known for the breadth and depth of her evidence, and the examples in Homo Aestheticus are typical. An anthropologist during the early 20th century observed villagers gathering to chant together during a terrifying storm in the Kiriwina Islands, east of Papua New Guinea. “Whether or not the gale subsided,” Dissanayake wrote, “the measured rhythm of the chanting and the sense of unity it provided would have been more soothing than individual uncoordinated fearful reactions.” Around the same time, half a world away, the Titanic struck an iceberg. As the vessel sank, the ship’s orchestra played “Nearer My God to Thee,” an instance, Dissanayake says, “of the same impulse to do something in the face of that anxiety.”

She began airing her ideas in a few scholarly journals in the late 1970s, to startling effect. Psychologist Jerome Bruner, the renowned zoologist Desmond Morris, and other intellectuals became fans of her work. A New York City philanthropist was so taken with her ideas that he sponsored a lectureship for Dissanayake at the New School for Social Research. Those years were like an independent scholar’s nirvana. Dissayanake’s only duty was to teach a weekly seminar and follow her ideas. “It was an amazing period,” she says. “The courses I taught found their way into my later books, because I’d spend six days a week preparing for the lecture, and one day giving it.”

***

Petroglyph panel, southern Utah, approximately 750-900 A.D.

When her three-year endowment ran out, she faced a turning point. “I decided not to return to Sri Lanka,” she says. “I knew the scholarly opportunities that had opened up to me would disappear if I returned. My husband tolerated my work, but he wasn't gung-ho about it. And I wanted to keep exploring these ideas. It was no longer a pastime. It became a necessity.” Though she and S.B. Dissanayake are no longer married, they remain on good terms and occasionally travel together.

It was hard to find a place for her work even at the New School, an institution known for its openness to off-beat and interdisciplinary ideas. She taught now and then, but she remained a scholar in a subject without a department. “People in the sciences didn’t want to deal with art because they thought art was vague and wishy-washy,” Dissanayake says, “and people in the arts didn’t want to deal with biology because it was messy, animalistic and they felt humans had a higher nature.”

Redemption came with publication. After being rejected by a number of publishers, the manuscript of What Is Art For? landed on the desk of University of Washington Press senior editor Naomi Pascal in 1985. Pascal, a legend in the world of academic publishing, retired in 2002 after a 49-year career at UW Press. She recalls Dissanayake’s manuscript as one of her most thrilling over-the-transom discoveries.

“Nobody had ever heard of Ellen, but I was immediately intrigued by the title,” Pascal says. “I thought, well, let’s see what it is. I read it and came away greatly impressed.” UW Press, known for its strong list in both art and anthropology, took a chance in back ing the work. “Ellen didn’t have the advanced degrees and academic affiliations that most authors of this kind have,” says Pascal.

The risk paid off. What Is Art For? became a hit in both the arts (among art historians and arts educators) and the sciences (among evolutionary psychologists). A reviewer in the scientific journal Nature called the book “one of the most intellectually enriching interdisciplinary studies of art that has ever been written.”

Which isn’t to say she was embraced by the academy. When What Is Art For? appeared in 1988, its author paid the rent by working as a transcription typist in New York. The critical success of that book led to a $5,000 advance from The Free Press for her second book, Homo Aestheticus. Unsure of how to market the book, the trade publisher put it out with little support and let it slip out of print after 18 months. When Dissanayake mentioned the book’s availability to Naomi Pascal, the UW Press editor snapped up the rights and brought Homo Aestheticus back into print in a paperback edition, which has gone through four printings and two foreign translations.

Dissanayake brought her third book to UW Press right from the start, though she had to get creative to write it without a trade publisher’s advance. “New York had grown too expensive to survive on a transcription typist’s wage,” she recalls, “so my parents, who live in Port Townsend, invited me to stay with them and write.” After defining art as “making special” in What Is Art For? and further exploring its evolutionary value in Homo Aestheticus, Dissanayake wanted to investigate the parent-infant bond and its role in the emergence of art, especially the way primal emotion is expressed through sound (music) and movement (dance). She came back home to the Pacific Northwest and wrote much of Art and Intimacy from the “personal writer’s colony” of her parents’ house, borrowing technical neuroscience tomes through inter-library loan and employing the Jefferson County Library bookmobile as a scholar’s delivery service.

It’s that kind of vigor and audacity that has attracted admirers throughout North America and Europe, where she’s often asked to speak at conferences, symposia and art museums. Dissanayake is pulling off a nearly impossible feat, pushing the boundaries of an emerging field with rigorous scholarly work while supporting herself entirely with her writing and speaking fees (her UW appointment is unpaid). “She’s strong willed, well informed, and an original thinker,” says David Barash, the UW evolutionary psychologist and co-author of Madame Bovary’s Ovaries, a work of literary Darwinism that explored the innate patterns of human behavior on display in classic books. “I’m not sure I agree with all of her interpretations, but I have no doubt that she has a big chunk of the truth.”

***

Art from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing.Jewel Samad

Four years ago the UW's Simpson Center for the Humanities invited Dissanayake to become a visiting scholar. When that two-year term was up, the School of Music gave her standing as an affiliate professor. The music education program has proven to be a nurturing home, providing her with library privileges, a fertile intellectual environment and the institutional affiliation that can be useful in placing articles and securing speaking engagements. The music school, in return, enjoys Dissanayake's presence at departmental seminars and symposia.

“Some of the questions we’re often asking are, ‘How early do humans start acquiring rhythms and melodies? Where does musicality begin, and why does it exist?’“ says Patricia Shehan Campbell, head of the UW’s music education program.

“Ellen looks at art and musicality from an evolutionary sense, but also from a developmental sense — how music functions as part of early mother-child interactions. She’s helping us understand that children coming into their school years aren’t blank slates, they’ve been acquiring complex motor and aural behaviors almost from the day they were born.”

Her relationship with the School of Music has also allowed Dissanayake to reconnect with her lifelong love of music, and to consider questions about its origins. In the past year she has published articles on the cultural origins of the musical lament (“how humans make crying special,” she says), how musical speech shapes emotion in infants, and the role of music and dance in human ritual and evolution.

Dissanayake continues to follow new ideas wherever they take her. A few years ago the ethnolinguist Ekkehart Malotki, an expert in Hopi language and culture, stumbled across Homo Aestheticus. “It was like an epiphany,” Malotki says. “She opened my eyes to a view of the pre-modern arts that I’d never encountered.” Malotki has since invited Dissanayake to collaborate on a book examining the rock art of the American Southwest. “That’s my next project,” Dissanayake says. “I want to know what that rock art had to do with survival thousands of years ago.”

Her highwire act — working as a scholar without a net — isn’t one she’d recommend to others. “It was hard to be taken seriously, and sometimes it still is,” she says. “I was a complete nonentity for years and years.” Even as her work is becoming known and appreciated among a wider audience at the UW, her appointment as an affiliate professor is nearing its two-year term limit. But for Dissanayake, the freedom to pursue her ideas wherever they take her, regardless of the boundaries imposed by academic disciplines, outweighs the drawbacks of the independent life.

“I really am seeking the truth,” she says. “I believe these things that I write about. And I couldn’t have written my books if I’d stuck to one field. I don’t want to concentrate solely on art history, or developmental psychology, or anthropology. I want to be able to pull ideas and evidence from all those fields together. I want to follow all these roads and find where they lead. It’s very freeing. If I need to know something, I find it out.”