Elevated awareness Elevated awareness Elevated awareness

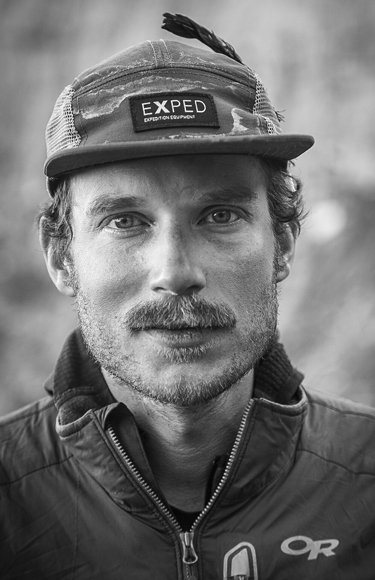

Alpinist and climate advocate Graham Zimmerman reflects on two decades of climbing some of the world’s highest peaks.

Alpinist and climate advocate Graham Zimmerman reflects on two decades of climbing some of the world’s highest peaks.

Like many athletes in the mountaineering community, alpinist Graham Zimmerman knows what it’s like to face death. As someone who regularly puts himself in precarious positions tens of thousands of feet up steep, icy mountain faces, Zimmerman has always been aware of the dangers of his sport. He’s awakened up to the news of friends and colleagues losing their lives or suffering severe injuries. Despite a few close calls—a broken leg and shattered shoulder from an avalanche in New Zealand, falling into a tight crevasse in the Alaska wilderness—he has always made it home at the end of the day.

“If you engage with enough risk, there will be times when it gets you.”

Graham Zimmerman

“It’s not guaranteed,” Zimmerman says over Zoom from his home in Bend, Oregon, where he lives with wife Shannon McDowell and their two Australian Labradoodles, Pebble and Iggy. “When you’re working with risk to life and limb, you have to be really careful. I’ve done a lot of work building models and methodologies for myself that allow me to go into [the mountains] and engage with that risk in a way that has a high likelihood of me coming home in one piece. I haven’t nailed it all the time—if you engage with enough risk, there will be times when it gets you. And that’s a frank reality for me as a climber and member of this community.”

Mountaineering, like many things, is a numbers game. You can be the most cautious, aware and skilled practitioner and still end up in situations full of unpredictability, from inclement weather to shifting topography. When climbing with a team, each person must trust the capabilities and knowledge of everyone else involved. Sometimes, when tragedy strikes or danger arises, it’s merely the act of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Most of us who have never had a near-death experience cannot begin to comprehend what those moments are like.

According to Zimmerman, at least, it’s nothing like the movies. There’s no grand montage of one’s life, no thoughts of loved ones and no deep philosophical meditation. Instead, as he writes in his debut book, “A Fine Line: Searching for Balance Among Mountains” (released in October 2023 through local publisher Mountaineers Books), “It’s an odd thing to consider how you are going to react when you are about to die, but in that moment, I received my answer. It came in a long string of expletives as the hidden snowbridge beneath me collapsed and I fell into a crevasse. The world slowed as I felt myself bouncing between the walls as I accelerated downward. One ski popped off as my knee twisted. I came to a quick stop, plugged into a constriction in the hole, the wind forced out of my lungs.”

Thankfully, Zimmerman’s climbing partner, Clint Helander, was able to locate him and, after an hour of constructing a complex pulley system, help him out. But the remote wilderness where the men were climbing (the Revelation Mountains are at one end of the Alaska Range, about 130 miles southwest of Denali) and Zimmerman’s injured knee made for an arduous return to their base camp.

Zimmerman is breaking ground using the knowledge gained from more than 40 expeditions and assignments around the world to help deal with climate change.

When asked why he keeps climbing despite the risk, Zimmerman—the director of Athlete Alliances at the Colorado-based nonprofit Protect Our Winters and the president of the American Alpine Club—looks away from his screen and pauses. “One of the things that I value most in life is learning,” he says. “When I think about the places in which I learn the most, they are places where I’m taking a strategic risk. When you have an accident or an injury, and you do the work to get out on the far side of it, then what do you do? Do you ignore it, move on and totally pivot your lifestyle—or do you look for hard lessons in the experience and register them in a way that makes you better moving forward? There isn’t a right or wrong choice, but in my life, it’s been pretty consistent that the lessons I get from the mountains make it worth going back for more.”

I reconnected with Zimmerman in 2011 when he was back in Seattle recovering from a climbing accident in New Zealand. We both attended Edmonds-Woodway High School in the early aughts and became friends before he went off to the University of Otago to study geography. (Born in New Zealand, Zimmerman is a dual citizen.) I still have memories of hanging out at Zimmerman’s house in high school, big groups of kids gathering in his parents’ basement to listen to Elliott Smith and Bob Dylan. What stands out most in my mind is the climbing wall that Zimmerman installed in his bedroom—the colorful handholds scaling up his wall and ceiling to indicate his budding passion.

“It’s funny,” he says, “usually, if you talk to someone who has dedicated their life to a sport, they will tell a story about the first time they experienced it, immediately knowing that they had found their ‘thing.’ When we were in high school, and I first went climbing in the mountains, I remember being scared and tired and getting badly sunburned. I do not remember it being fun, and I do not remember being like, ‘This is my thing.’”

For Zimmerman, the draw to climbing was more complex, driven by a comfortable suburban teenage life in a safe community where you could practically leave your front door unlocked. “When I went to the mountains, I was challenged in a way I had never been before,” he reflects. “I also experienced a new level of agency with decision-making, which I found empowering.”

By the time Zimmerman was 18 and heading to New Zealand for college, climbing was the only thing he wanted to do. Like most industries at the time, mountaineering had a masculinity problem. As a culture, it appeared overrun with swaggering men competing to see who could climb the highest or on the most complicated routes—an allegiance to anything other than the mountains indicated weakness and was a waste of time. Zimmerman admits that his younger self got caught up in that mentality for a while, but part of his motivation for writing “A Fine Line” was to help change that adverse narrative.

A keen observer, Zimmerman used the skills he learned from a UW storytelling program to write his first book.

“The body of climbing literature and core climbing stories still trend toward this macho, Nietzschean Ubermensch mentality,” he says. “I wanted to present a different perspective and show that to have a life in which climbing is a crucial part, but not everything, doesn’t make you a worse climber. Learning how to balance different elements such as relationships and advocacy gave me a foundation and the tools to try bigger and harder things and have the outcomes of those objectives be even more profound.”

After graduating from Otago, Zimmerman returned to the U.S. and took up a peripatetic lifestyle that included the esteemed Yosemite Search and Rescue team, which specializes in rescues from the big walls of Yosemite National Park. He also worked for MWH Geo-Surveys, running gravitational surveys in Kenya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Northern Canada and the Southwestern U.S. It was a lucrative job that allowed him to travel internationally and funded his climbing trips between assignments. Then, one day, he checked in on a project he’d worked on in Eritrea. Instead of providing economic and educational opportunities for local communities, the mine that had resulted from the mapping they did “had led to allegations of forced labor, slavery, and torture,” he writes. “No longer could I ignore the impact of the work I was doing in an extractive industry. It created stability for me in the form of a reliable income, but it was immoral and not sustainable for the world.”

Armed with this knowledge—and the growing realization that climate change was negatively and alarmingly impacting the environment—Zimmerman decided it was time to realign his values and actions. In 2019, he got involved with Protect Our Winters, a nonprofit organization in Boulder, Colorado, that focuses on law reform for environmental issues. He also started leveraging content from his climbs to bring awareness to the human impact on the planet. Zimmerman has participated in the production of more than a dozen films for clients such as REI and Outdoor Research.

“I didn’t get into policy or advocacy sooner because of a perceived hypocrisy around my carbon footprint,” Zimmerman admits. “I felt like I was a big part of the problem. Now, I see myself as an imperfect advocate. I am using my platform as a professional athlete and community leader to pressure politicians into hopefully driving systemic climate-solution changes. In my role at Protect Our Winters, I empower other professional athletes to do the same.”

A leader in every sense of the word, Zimmerman stands out in the climbing community for his openness, emotional maturity, levelheadedness and ability to inspire others. A dedicated team player, he talks about strength in numbers, admitting when he doesn’t know something, and the importance of bringing people onto a team who can fill in those knowledge and skill gaps. “You can make a stronger team that way and accomplish more in the long run,” he says.

“A lot of people attracted to the mountains are misfits,” says mountaineer and author Steve Swenson, ’77, who, in addition to summiting Mount Everest and K2 (the two tallest mountains on Earth) without supplemental oxygen, is known for his climbing expeditions to the Karakoram, a range in the Kashmir region that spans the borders of Pakistan, China and India. Swenson has climbed with Zimmerman a handful of times, including the first summit of Pakistan’s 23,100-foot Link Sar with fellow climbers Mark Richey and Chris Wright. For their efforts, the team was awarded a 2020 Piolet d’Or Award—the highest honor in alpine climbing. “A lot of climbers are awkward, and it’s hard for them to know how to fit into a crowd or take on a leadership position. Graham is unique in that regard. He is much more emotional and apt to express gratitude and appreciation. What impressed me about Graham on our first trip to Pakistan was his willingness to be open and learn,” Swenson says.

Zimmerman performs yoga in the rain while on an expedition in the Karakoram.

In the past two decades of his climbing career—in which he has participated in expeditions in locations including Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Alaska, Argentina and New Zealand—Zimmerman has become one of the most acclaimed alpinists of his generation. Like Swenson, his focus is “big mountains” that are technically challenging. He avoids fixed-rope routes, opting to bring what he can carry on his back and climb with only a length of rope tied between two climbers. First ascents are a Zimmerman specialty—he has more than a dozen under his belt. “I’m working on this personal goal of opening one new route each year,” he says. “That’s not always a big mountain. I’m also trying to open routes accessible to the broader community.” In 2022, Zimmerman and fellow climber Ian Nicholson worked on establishing Washington’s Edge of Time Arete, a 650-foot alpine rock climb near Snoqualmie Pass.

Like Swenson, mountaineer and photographer Kaj Bune, who works in the marketing department at EXPED, a Swiss outdoor gear retailer, has known Zimmerman for years. A friend of Zimmerman’s father, who played Ultimate Frisbee with him in Seattle in the 1970s, Bune met his friend’s son when he gave a talk to Zimmerman’s high school mountaineering club. The two have since climbed together in Washington state, and Zimmerman counts Bune as a career mentor.

“Graham is always listening and taking in things from everyone he encounters. That’s one of the keys to his ability to be a leader.”

Kaj Bune, mountaineer and photographer

“Graham has an abundance mentality,” Bune says. “He understands and acts upon the idea that you can give someone else credit, compliment them, or recognize that they have contributed to your achievements, and it doesn’t take away from your success. Graham is always listening and taking in things from everyone he encounters. That’s one of the keys to his ability to be a leader.”

Examples of this are laid out over and over again in “A Fine Line.” Zimmerman recognizes the power of storytelling and uses his voice—authoritative, funny and sharp—to craft a beautifully self-aware memoir exploring his evolution from a couch-surfing climbing obsessive into an emotionally engaged husband embracing balance to achieve a more fulfilling life. In 2020, Zimmerman enrolled in a yearlong course at the University of Washington, earning a certificate in Storytelling and Content Strategy, which he credits with helping him to write his book and to better approach marketing for the climbing organizations he’s involved with.

“If you look at how people were getting to the conversation about climate change in the late ’80s through the early aughts, there was this approach if we hit communities with enough facts, they will eventually come around,” Zimmerman says. “But people ultimately hit this threshold of facts and will stop listening. We’re trying to move away from that and leverage stories from within communities in order to create common ground. The age-old tradition of storytelling—think about gathering around the campfire for thousands of years—is really powerful.”

On or off the mountain, Zimmerman cuts an inspiring figure. His humble attitude underscores the power of leaning into self-reflection and ultimately learning to love deeply and vulnerably. In the book, he lays bare the story of meeting his wife, the courtship that followed and his eventual dropping of the mental and emotional barriers that often keep people at a distance. Through shared elite-level athleticism (Zimmerman’s wife is a two-time world champion Ultimate Frisbee player), the two found a unique common ground where they support and understand each other. But the love doesn’t stop there. Zimmerman demonstrates what it’s like to walk through the world with openness and curiosity—to embrace every day with enthusiasm and hope for the future.

“Graham uses the word love regularly,” Bune says. “Not just in the book, but in everyday life, he is willing to talk about big mountaineering and love in the same sentence, and that’s a pretty rare thing. Anyone invested in these activities for a long time is feeling that emotion, but Graham is willing to say it out loud again and again. Love—that’s the reason why any of us are out here doing this in the first place.”

In recent years, Zimmerman has chosen to reevaluate the length and types of climbing trips he undertakes (a 2021 attempt to summit the rarely climbed, challenging West Ridge of K2 was abandoned when he and his climbing partner encountered uncharacteristically warm temperatures), a decision he sees as a marker of maturity and growth rather than weakness or failure. “It’s getting harder to justify trips like that K2 climb,” he says. “I’ve seen a lot of loss in my career. We need to make sure we are bringing the folks we lost along with us by celebrating and remembering them and locking their stories into our core ethos for many years to come. I hope my book serves as a reminder of all the remarkable things they’ve done.”