Secrets of the deep Secrets of the deep Secrets of the deep

Historian Coll Thrush researches the dark history of Pacific Northwest shipwrecks in "Wrecked."

By Hannelore Sudermann | December 2025

Somewhere off Cape Flattery on a November night in 1875, the SS Pacific met its end amid strong winds and deep ocean swells. The aged sidewheel steamer had just left Victoria for San Francisco, her decks packed with miners, merchants, families and 41 Chinese workers, her hold filled with goods from Canada and treasure from the Cassiar Gold Rush in British Columbia. Around midnight, another ship crossed her path. The two collided, and within half an hour the SS Pacific broke in two and sank beneath the waves. Of an estimated 300 passengers, only two survived. For six weeks afterward, debris and bodies washed ashore. Newspapers called it a fearful disaster. Today, it remains one of the worst maritime calamities in Northwest history.

A scholar of Indigenous and colonial histories, Coll Thrush explores nature, power and memory through the stories of the Pacific Northwest’s shipwrecks in “Wrecked.” Photo courtesy of Coll Thrush.

A century and a half later, historian Coll Thrush, ’98, ’02, stands before a Seattle audience recounting the story of the SS Pacific and other shipwrecks from his new book, “Wrecked: Unsettling Histories of the Graveyard of the Pacific.” While the tragedy of the SS Pacific is well-known, Thrush reminds his listeners that in a region once entirely reliant on maritime trade and transport, “shipwrecks were more frequent than we might imagine.” At the time of colonial settlement, shipping was the only connection to the wider world, and the coasts of Oregon, Washington and Vancouver Island were particularly treacherous, the weather particularly unpredictable. “A single storm could take out 10 ships,” he says.

Thrush, who earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. in history at the University of Washington, spent six years combing through archives, oral histories and ship logs to unearth tales of sinking and survival, exploitation and tragedy. But in the process, he discovered a deeper narrative—an exploration of how people, place and power collided along the Northwest coast, and how nature always won.

Growing up in Auburn in the 1970s, Thrush was drawn to ghost stories. Family trips to the Washington coast thrilled him—the beaches, the go-karts, the arcades and candy shops. But what captivated him most was the wreck of the SS Catala, a 1925 steamship that in the 1960s had broken loose of its moorings and lodged in the sand near Ocean Shores. That sense of wonder stayed with him, he says.

Decades later, at a conference, the University of British Columbia professor noticed a poster showing shipwrecks along the coast. “I stood there staring at it,” Thrush recalls. “I realized I already knew half those stories. And then I thought, what about the others?”

Digging into newspaper databases and ship manifests, he noticed patterns. The shipwreck stories weren’t just about the sea—they were about ambition, adventure and imperialism. “I turned to Indigenous histories to find alternative views,” he says. In most cases, it was Indigenous people who, risking their own lives, rescued survivors. They salvaged cargo and passed down oral histories of the events. “Every wreck happened in Indigenous territory,” Thrush says. Indigenous people were there—witnessing and remembering. The history has always been theirs, too.

What began as a maritime chronicle became a cultural excavation. Until recently, mainstream history of our region focused on settlement moving west across land, but, Thrush says, many scholars have neglected to study colonialism from the sea. “Most of us don’t have much of a relationship with the outer coast anymore,” he says. “We think of it as scenery or a place to escape on weekends. But for most of our history, the sea was the heart of everything.”

“For most of our history, the sea was the heart of everything.”

Coll Thrush, 98, '02

A member of Gen X, Thrush grew up “hopped up on ghost stories” in a darker version of the Pacific Northwest—the era of the Green River Killer, the declining timber industry and “Twin Peaks.” “That for me really shaped my sense of the landscape as this place of danger,” he says. “It’s this beautiful place, but also haunted.

“I think in terms of broader Northwest history, Gen X occupies a space between the optimism of the ’60s and explosion of capital in the ’90s. We kind of grew up in that middle space, where things weren’t great,” he adds. “I think this is just the coolest place in the world, but it has got a really dark past and present as well.”

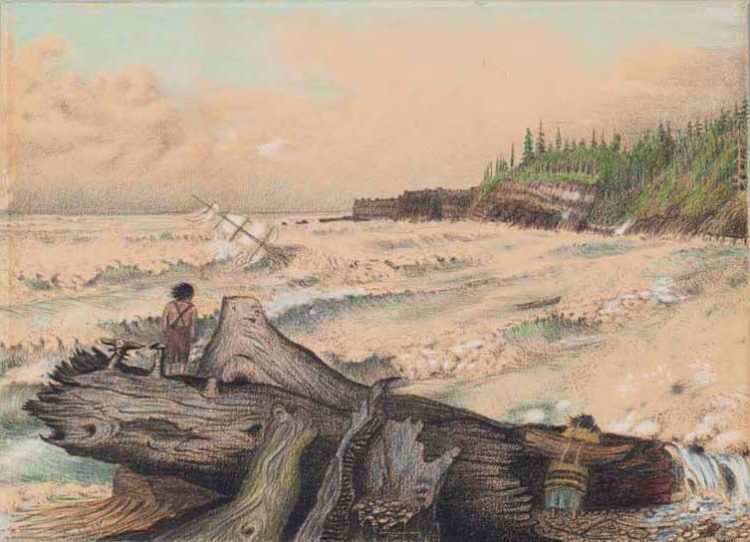

- The Sir Jamsetjee Family wrecked in 1887 near the mouth of the Quinault River en route to Port Townsend. Members of the Quinault Nation rescued the crew, all of whom survived. Credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, creator, Sarah Willoughby, NA4036

- Docked at Yesler’s wharf in 1875, the SS Pacific (pictured on the far left) sank near Cape Flattery later that year after colliding with another ship. Credit: MOHAI

Raised near the Muckleshoot Reservation, Thrush had an early awareness of “other histories that didn’t get talked about” and layers of history all around him. It became a personal quest to understand what it means to belong in a place that was not historically his.

As an undergraduate at Western Washington University, he took a course called “The Historian as Detective” that changed his path. “That class saved me from law school,” he says. “It also showed me that historical research was actually a process where I get this ‘sense of place’ stuff.”

Thrush researched history for the Muckleshoot Tribe, deepening his understanding of Indigenous perspectives. “Claiming place is a political act,” he says. “It’s about who belongs and who gets to tell the stories.”

His first book focused on Indigenous and urban histories, exploring Seattle’s founding considering the roles tribal communities played and highlighting accounts from Indigenous perspectives. “But I never thought I’d write about shipwrecks,” he admits. “I am not a maritime historian.”

As he dug deeper, the wrecks revealed themselves as tied to ideas more profound and complex than the calamities themselves. “It changed the whole project,” he says.

One of his most exciting discoveries, he says, was the story of the Peter Iredale, a four-masted steel bark, which ran aground on Clatsop Beach on the Oregon Coast in 1906 and immediately became a tourist attraction. In the book, the ship appears between chapters, slowly decomposing over time. Thrush tracked down the owner’s descendant, who had done genealogical work and discovered that the vessel was connected to the slave trade. “It was amazing to be able to capsize that story so it’s not just nostalgia but about how this part of the world is connected to the rest of the world, and how power is tied to these ships as well,” he says. “I realized this was something to hang the whole book on.”

Thrush was also struck by the significant presence of Indigenous voices. “It wasn’t that they were hidden; they were just ignored,” he says. “These weren’t just maritime accidents—they were events that took place on Indigenous shores, in Indigenous homelands.” Oral histories recorded in the 1920s described a little-known Russian shipwreck that took place in the previous century—evidence of the endurance of memory. “The knowledge practices in Indigenous communities were strong, and they preserved details” that the written record never captured, Thrush says.

“Wrecked” is much more than a thrilling catalog of ocean disasters. One of the Kathleen Sick Book Series from UW Press, it details shipwrecks as moments when technology, commerce and colonial expansion literally crash into nature. “They’re the points where the illusion of control breaks apart,” Thrush says. Some wrecks, like the Valencia, were national news—more than 130 people were lost off Vancouver Island in 1906. Others were quieter, smaller vessels swallowed without a trace. Altogether they chart a century of risk, greed and resilience along one of the most perilous coastlines in the world.

“Wrecked” is much more than a thrilling catalog of ocean disasters. One of the Kathleen Sick Book Series from UW Press, it details shipwrecks as moments when technology, commerce and colonial expansion literally crash into nature. “They’re the points where the illusion of control breaks apart,” Thrush says. Some wrecks, like the Valencia, were national news—more than 130 people were lost off Vancouver Island in 1906. Others were quieter, smaller vessels swallowed without a trace. Altogether they chart a century of risk, greed and resilience along one of the most perilous coastlines in the world.

Thrush’s approach has struck a chord in a region still developing its identity. “Coll brings a fresh lens to a long-popular subject,” says Professor Joshua Reid, director of the UW Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest and editor of the Sick series. “He’s taking stories that were once about adventure and tragedy, and showing how they connect to power, to Indigenous presence, to the modern world. It’s rigorous scholarship, but it’s also masterful storytelling.”

While previous maritime histories celebrated courage and progress, “Wrecked” is an exploration “against that narrative of expansion,” Thrush says. And an opportunity to bring more of our maritime past to the surface.

One hundred and fifty years later, the SS Pacific has literally resurfaced. In 2022, explorers led by UW alum Jeff Hummel located its remains. For Thrush, the discovery was more than proof—it was metaphor. “These ships not just staying in the past is really critical to this story,” he says. “The past isn’t past. It keeps coming back.”