At 6 a.m. sharp, the Congressional swimming pool in Washington, D.C., opens for business. Without fail, Tom Lantos is first in line, champing at the bit to begin his daily ritual of 45 minutes of swimming laps.

It’s just the beginning of another long, grueling day of meetings, hearings and deal-making for the 71-year-old Democratic representative from the 12th Congressional District in California. But it’s one he tackles with unfettered passion and awe, especially when he sees the American flag flying on top of the Capitol building as he makes the short walk from his apartment to the office every day.

“I want to make the most of life,” says Lantos, who is in his 20th year in Congress. “I like to work hard to make this a better country, to provide a just government for our people and make sure we have learned from the past.”

The past defines this University of Washington alumnus in a way few of his fellow former classmates know. Lantos is the only Holocaust survivor ever elected to Congress. A Hungarian-born Jew who grew up during the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, Lantos is one of five people featured in the Academy Award-winning documentary The Last Days. The movie was executive-produced by Steven Spielberg and his Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to videotaping and archiving interviews of Holocaust survivors the world over.

Lantos in his commencement apparel after graduating from the UW. Photo courtesy of Tom Lantos.

A leading human rights statesman, he’s an expert in foreign policy, and a force in investigating government waste, fraud and mismanagement.

When people tell him his daily schedule is crazy, he just laughs. After all, handling his myriad duties in the nation’s capital, jetting 3,000 miles back home to his upper-middle class district south of San Francisco, and keeping up with his wife, two grown daughters and 17 grandchildren is nothing.

“Compared to what I have been through,” he says, “this is easy.”

Born the only child of upper-middle-class Jewish parents in Budapest in 1928, Lantos grew up during a time when Hungary was slowly being taken over by the Nazis. When he was 10 years old, he bought his first newspaper—an experience he vividly recalls today. The headline read, “Hitler Marches into Austria.”

“I sensed that this historic moment would have a tremendous impact on the lives of Hungarian Jews, my family and myself,” he says. If only he knew.

When he was 16, German troops invaded his homeland—and along with them came Adolf Eichmann, with orders to exterminate the Jewish population of Hungary. By the end of the summer of 1944, most of the Jews outside of Budapest had been sent to Auschwitz.

Lantos and other young Jewish men were sent to work camps. He was dispatched to Szob, a town 40 miles north of Budapest, where his forced labor group’s duty was to maintain an important bridge on the Budapest-Vienna rail line.

The work was treacherous at best, and he experienced wild highs and lows—delight at watching Allied bombers destroy the bridge, yet frustration because he knew it meant he and his comrades would have to rebuild it. Then there was the day an air raid killed all the young workers except Lantos. “I was convinced I wouldn’t survive,” he says.

“In retrospect, I was doing things I never should have done, because they took more courage than I'm sure I had.”

Tom Lantos

Despite his imprisonment, he managed to keep in contact with his family, and Annette Tillemann, a childhood friend who went into hiding with her mother shortly after the German invasion. Once, Lantos escaped from the camp but he was caught and “beaten to a pulp.”

Desperate with what his life had become, and feeling he had nothing to lose, he tried another escape. When a guard wasn’t paying much attention, he disappeared. His blue eyes and blonde hair fooled Nazi troops into thinking he was not a Jew, but the entire time he was trying to make his way back to Budapest, he was wracked with fear that his Jewish identity would be discovered if he were ordered by a Nazi soldier to drop his pants.

He eventually found refuge in a Budapest apartment building rented by Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg and under Swedish diplomatic protection. Wallenberg saved approximately 100,000 Hungarian Jews with his secret refuges and by providing fake Swiss passports. (To this day, Lantos remains deeply indebted to Wallenberg for saving his life. A portrait of Wallenberg—who disappeared after being imprisoned by the Russians—hangs behind his desk in the Rayburn House Office Building.)

“It was a three-bedroom apartment designed for one family,” Lantos recalls, “And there must have been 50 to 60 people crowded into it.” Noting Lantos’ “Aryan” coloring, Wallenberg put Lantos to work helping out in an elaborate anti-Nazi underground, delivering a bottle of medicine or loaf of bread to Jews Wallenberg had in hiding throughout Budapest. Dressed in a military cadet’s uniform, Lantos was able to move around undetected by Nazi authorities. His good deeds, however, were not based strictly on altruism or a desire to help his fellow man, but fatalism. “I probably wouldn’t survive,” Lantos thought at the time. “I decided I might be of some use.

The Nazis used Jewish labor battalions to build and repair important communication links and bridges and to dig trenches on the Eastern Front. Lantos was forced to work in a battalion similar to this one. Photo courtesy of Film and Photo Department Archives, Yad Vashem Museum, Israel.

“In retrospect, I was doing things I never should have done, because they took more courage than I’m sure I had.”

As the war entered 1945, life in Budapest deteriorated. It was under constant shelling and the Germans and Russians engaged in house-to-house fighting. Then, at 3 a.m. on a cold January day, a Russian soldier burst into the safe house where Lantos was staying, liberating the teen-ager and his many housemates. By mid-January, the German army pulled out, leaving the Russians in control of the city. But Lantos’ relief was short-lived—a search for his mother and the rest of his family ended in vain. They had all been killed.

Miraculously, Lantos was able to re-establish contact with Annette Tillemann, his old childhood friend who had gone into hiding during the German invasion. All he had was an old address of some of her family friends in Switzerland. He was not aware that Annette and her mother had escaped to Switzerland. He sent a letter, and somehow, even though the Hungarian postal system was in disarray, it got through. Stunned and thrilled to learn that Lantos was still alive, Tillemann was desperate to contact him. Knowing it was impossible to reach him by mail, she gamely boarded an old bus for an excruciating 10-day journey back to Budapest, with nothing more than a tiny parcel containing some food.

Her homecoming was devastating. She learned that her father, grandparents and all but one relative who remained in the city had been killed. But she was able to get word to Lantos that she was back in town, and after a year’s separation, they were reunited. They would never be apart after that, and in fact, are still together after 49 years of marriage.

Once the war was over, Lantos began his studies, first in medicine (“until they brought in the first corpse, and I was through with medical school”), then economics at the University of Budapest in the fall of 1946. The following summer, he was awarded a Hillel Foundation scholarship to study in the United States. “I saw this little notice on a bulletin board for the University of Washington, in a place called ‘SEE-tle,’ ” he recalls, purposely mispronouncing the city’s name to show how unfamiliar he was with it 50 years ago. “I never dreamed I had a chance. I was stunned when they called me in to tell me I was going to study there.”

He landed penniless in New York City in August 1947, with only a prized Hungarian salami, which was confiscated by U.S. Customs officials, to his disappointment.

His arrival in Seattle—this city he had never heard of—was like Dorothy landing in Oz. “Totally unreal,” he says. “Here I was, coming out of the Holocaust, starvation, poverty, persecution, the worst horror of mankind, and I had landed in this bucolic setting. People were friendly and wonderful, there was all the food I could eat. I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

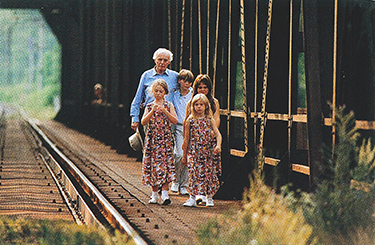

Lantos returns with four of his 17 grandchildren to the bridge in northern Hungary where he was forced to work in a labor battalion during the German occupation of Hungary. Photo by Geoffrey Clifford.

Despite being in a foreign land, Lantos felt right at home. He joined a fraternity, Sigma Alpha Mu, where he spent three fun-filled years while studying economics, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1949 and his master’s in 1950. Howard Nostrand, then a professor of romance languages, even had Lantos over for Thanksgiving during his first year. “He came into my office one morning, saying he needed work,” Nostrand, now retired, recalls. “He said I resembled his father. We were quite close. He was a very promising student, a person of marked intellectual curiosity. He was always asking questions.” The two remain in touch today.

Enjoying his new life with unbridled enthusiasm, Lantos jammed as much as humanly possible into each day. In addition to a full load of classes, he had an armful of part-time jobs: he ushered at the Seattle Symphony in a borrowed tuxedo, he worked nights stacking shelves at a local grocery store, he tutored Latin, German, French and Italian, and he delivered furniture. He also was the “sandwich man” on sorority row, selling sandwiches, milk, and other goodies to students.

“I worked very hard,” he says. “A lot of old people were depending on me in Hungary. I was a great entrepreneur.” With some of the money not used for tuition and living expenses, he bought chocolate and other supplies and sent them to relatives and friends in Hungary every week.

“I was full of energy,” says Lantos, who also managed to fit in swimming in Lake Washington, jogging and playing tennis. “You have to remember, getting beyond World War II, I felt like I was born again. It was so much fun. I took a lot of joy in everything life had to offer.”

While a student here, he approached Nostrand, looking for more work, and convinced the French professor to hire him to teach Hungarian at the ripe age of 19. (Lantos is fluent in five languages.) “It was more of a regional studies class, where we covered Central European history,” Lantos recalls. “It helped pay for my schooling.” It also made the UW only the second university in the nation to teach Hungarian (after Indiana University).

Lantos and his dog, Gigi.

It was also a way for Lantos to carry on a long-held tradition of teaching in his family. After leaving the UW—”it was the happiest time of my life,” he says with pride—he earned a Ph.D. in international economics at Cal-Berkeley, and began a 30-year career as an economics professor at San Francisco State University. Though he was moving up in the world, his work ethic didn’t slow down for a second. He also was a business consultant, developed his own public television program on international affairs, and was actively involved in state and national politics, his real love.

In 1978, he took a year’s leave of absence to go to Washington, D.C., to work as a foreign affairs adviser to Sen. Joe Biden (D-Delaware). He enjoyed it so much, he pondered running for Congress after the 1979 assassination in Guyana of Leo Ryan, the House representative from San Mateo. “But Sen. Biden reminded me that I promised to stay for the duration of my commitment,” Lantos says. “It was also a good thing, because had I run, I would have lost.”

In 1980, Lantos threw his hat into the ring against incumbent Republican Bill Royer, who succeeded Ryan. That move earned him ridicule from observers who said Lantos had no chance, never having held public office and running as a Democrat during a year when the Ronald Reagan-Republican movement was sweeping the nation. But beating the odds was old hat to Lantos, who defeated Royer to become one of only two Democrats nationwide to unseat an incumbent Republican that year.

That started in motion a political second life that has kept the confident, erudite Lantos in the public eye and fighting injustice for the past 20 years. He is known far and wide for his support of Israel, and for fighting government waste, such as his stint as chair of the committee investigating HUD scandals of fraud, influence peddling and political favoritism in the 1980s.

Lantos’ passion for good government knows no bounds. “My life’s experience taught me. I had seen what a police state does to people,” Lantos says. “I had to be a part of the policy part, to make things better. I have developed a lifetime love affair with politics and government. I take government very seriously. I have a passion to make sure we prevent others from going through what I did.”

“It was not an easy or pleasant task but I knew it would be a powerful and gripping reminder of this nightmare that must not be forgotten.”

Tom Lantos

Despite his national exposure as a longtime member of Congress, Lantos and his wife have rarely told their stories publicly. “I don’t want to relive that nightmare,” he explains. But back in 1995, when he was approached by the Shoah Foundation (“shoah” is Hebrew for calamity) for an oral-history project on the Holocaust, he agreed. When Spielberg’s foundation decided to make a documentary featuring some of those interviewed, director James Moll chose to feature Lantos among four other Hungarian survivors’ stories.

“I did it because I felt the educational value of the film for generations to come would be enormous,” says Lantos. “It was not an easy or pleasant task but I knew it would be a powerful and gripping reminder of this nightmare that must not be forgotten.”

For the making of the movie, Lantos returned with four of his 17 grandchildren to the bridge in northern Hungary where he was forced to work. They listened somberly as he tells his story.

Lantos was one of five Hungarian survivors asked to participate to show a representational view of what happened to the entire country. Each survivor and selected family members then traveled to Europe with the documentary film crew to revisit their homes, where they were imprisoned, and where they worked. The movie was shot on 35mm film, much of it with a handheld camera, had no narrator, and included rare footage to tell a single, unique chapter of the Holocaust while conveying a sense of its magnitude.

The movie, winner of the 1999 Academy Award for best documentary, is one part of the Shoah Foundation’s mission to videotape and preserve eyewitness testimonies of Holocaust survivors. To date, more than 50,000 videotaped interviews in a total of 57 countries and 31 languages have been gathered.

“For me to be where I am, given my background, is something I cannot possibly believe,” Lantos says. “Fifty years ago, I was a hunted animal in the jungle, and now I am dealing with issues of state of a country I love so deeply. It all seems like a dream, and it places an incredible sense of responsibility on me.

“It is why I will carry on.”