It is a story that hundreds of thousands of Huskies are living—but this one has a twist. In this version, a local kid does pretty well in high school and looks at his options. He works on truck farms harvesting vegetables and in the summer raises pheasants at a state game farm. His older brother is already away at college. To avoid too much of a strain on family finances, the younger son spends his freshman year at community college.

Finally his time has come. In the spring, as the cherry trees bloom in the Quad, he arrives at the University of Washington. It is an awakening. He hadn’t thought too much about his future—maybe he’d go to law school or maybe he’d race sports cars. But engaging with his professors and fellow students, he falls in love with the life of the mind.

That love of learning takes him to graduate school and launches a career in higher education. Running what he calls a “lap of America,” he gradually rises on the academic ladder until he becomes the chancellor of flagship research universities in the East and in the South.

That rise to success could have been the end of the story, but there is one more plot turn. When he gets a call from home, he can’t resist the opportunity to come back to where it all started.

And so, on June 14, 2004, Mark Allen Emmert, native of Fife and UW class of 1975, takes over as the 30th president of the University of Washington, the first time in 48 years that a UW alumnus will hold the reins of his alma mater.

Emmert’s background covers 21 years in higher education as a professor, associate dean, provost and chancellor. His last two positions were leading flagship public institutions: the University of Connecticut and Louisiana State University.

“This is a place that did so many things for me. What could be better than to make sure it is a place that continues do that for everybody else?”

Mark Emmert

Many of Emmert’s colleagues say this is his “dream job,” the one he has always wanted, even when he was in eighth grade. The normally articulate new president seems to hesitate when asked about coming back to Seattle. “I really can’t explain adequately what a great honor this is,” he says. “This isn’t just another university, this is my home, my alma mater. This is a place that did so many things for me. What could be better than to make sure it is a place that continues do that for everybody else?”

While Emmert is thrilled to be coming home, the University community is also thrilled to have a 17-month presidential search finally come to an end. Since former President Richard McCormick left for Rutgers in the fall of 2002, the UW has been buffeted by violations in its athletic department and billing fraud in its academic medical center. A melee in Greek Row damaged relations between the neighbors and the UW. Unhappy with their working conditions, the teaching assistants voted to unionize. Enrollment pressure was so great that the admissions office had to end automatic transfers for qualified community college students.

So while the 51-year-old Emmert is excited about the opportunity to lead one of the premier public research universities in the world—”the best on the planet,” he said at his first UW press conference—he also knows that he is facing a host of challenges with no easy solutions.

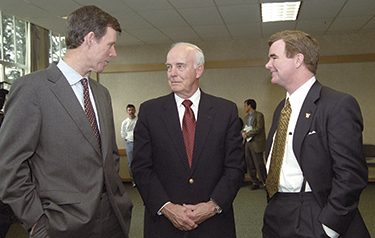

Left to right, UW Medical School Dean Paul Ramsey, who was cho-chair of the presidential search advisory committee, Regent Dan Evans, ’48, ’49, and incoming President Mark Emmert confer during a March 22 press conference at the UW. Photo by Kathy Sauber.

“To champion the cause of the University of Washington—its impact on society is so enormous and so positive—I’ll take that challenge,” Emmert says. “I can’t imagine doing anything else with my life. I think I am amazingly lucky to get a chance to do this.”

Not that it’s been an easy ride from the day in 1975 when he got his UW degree. While running his lap of America, Emmert has closed academic departments, expelled students after a spring riot, fired a football coach and comforted a campus terrorized by a serial killer.

He’s also been able to attract federal research dollars to a cash-poor campus, map out a $1 billion construction plan, win for his faculty an average 22 percent pay raise over four years, convince a state legislature to pour money into higher education (when most states were cutting back), persuade students to support a tuition surcharge, watch his schools’ teams win three major national championships—and help lure two sitting U.S. presidents to be speakers on his campuses.

He is constantly on the go, say his friends and colleagues, which may be why his 5-foot-9-inch frame shows no sign of a baby boomer’s bulge. He’s also avoided another curse of his aging generation—he has a full head of hair that seems to shift colors from brown to auburn depending on the light. He can be a stylish dresser and favors suspenders (several sets are reported to be purple and gold), but on the day of his interview he wore an open neck, short-sleeve shirt and khaki pants.

Even though he adores fly fishing, his office did not have a trophy trout mounted on the walls. Instead paintings on loan from the LSU art museum and a first edition of a book by Louisiana legend Huey Long. (Emmert says he’s always been a history buff.) In addition to fishing, he relaxes by skiing (both cross country and downhill) and boating. He and his wife, Delaine Smith Emmert, enjoy all the arts and have even done a play reading together for a $500-a-ticket fund-raiser.

On stage or in a conversation, Emmert speaks in a soft, deliberate manner. Unlike many academics, he will let the questioner finish the sentence before he starts giving his answer. His sense of humor is one of his trademarks. Those sitting in the LSU chancellor’s waiting area are often surprised to hear laughter burbling out of his office. He doesn’t seem to take himself too seriously; the butt of his jokes is usually himself.

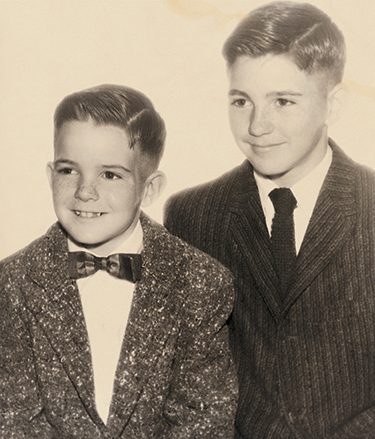

Mark Emmert (left) smiles with his brother, Steve, in this late 1950s portrait. Photo courtesy Mark Emmert.

It is a style born of the Pacific Northwest. Emmert and his wife are both third generation Washingtonians. His parents met at Fife High School—where Emmert and his wife would also later meet—and his dad served as an optics technician during World War II. After the war, he spent a long career as an optician with Binyon’s Optometrists in Tacoma. Emmert’s mom was a teacher’s aide and a homemaker. His parents are still living and still own his boyhood home.

Fife was a small farming town when Emmert was born on Dec. 18, 1952. “It was more rural than suburban,” recalls Jerry Herting, ’75, ’86, a childhood friend of Emmert’s and now a sociology professor at the UW. “There were dairy farms and truck farms. Membership in the Future Farmers of America was a major source of status in high school.”

Emmert’s aunt and uncle lived down the block, and he roamed the neighborhood with brother, Steve, who is three years older and his cousin, Frank Spear, ’79, ’85, who is the same age as Emmert and now a dentist in Seattle.

“You might describe it as Leave It to Beaver in the country,” Spear says. Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts, Little League, the youth groups at the family’s Presbyterian church—it was the archetypal American boyhood. But there was hard work as well as fun and games. “I worked all the time,” Emmert says. “I worked mostly for the local farmers such as Yamamoto’s truck farm. I grew up pulling lettuce and cutting cauliflower.” Later he raised pheasants for state game farm in Lakewood (he still occasionally goes bird hunting).

There were annual trips to the fair in Puyallup and several visits to the 1961 World’s Fair in Seattle, his cousin recalls. But the trip with the biggest impact was a middle school excursion to the UW campus. “I was just stunned by it. I had never seen anything like it,” Emmert says. “It was impressive and grand and scary all at the same time. It was like imprinting on a duckling. I remember thinking, ‘This is very, very cool.’“

Spear says it was at that moment that his cousin set his sights on the UW. “He has talked about wanting to be president of the UW since he was in eighth grade,” Spear says.

In high school Emmert says he was a “good student but not a great student.” Herting sees it slightly differently. “He was a smart guy; he just wasn’t breaking his back studying.” One social studies teacher got the young student interested in government and social sciences and geography. “If we’re lucky, we all have teachers who touched us, and I had Mr. Kitts,” Emmert says.

Emmert ran for student leadership offices, wrote and sold ads for the student newspaper and played basketball and ran track. “At 5-9, I was a forward. That tells you a lot about my high school,” he jokes.

It was in his junior year when Emmert met the most important person in his life—his future wife. Delaine Smith’s father worked for the Milwaukee Road railroad. The family moved all over the state and in 1969 its new home was Fife. Although brand new, she was trying out to be a cheerleader.

An excited Mark Emmert polishes his family’s 1965 Ford Mustang prior to driving it to the Fife High School prom. Photo courtesy Mark Emmert.

Fife High School had a democratic tradition for selecting its cheerleaders—the students got to vote on who would make the squad. Emmert enjoys telling the story about how he politicked with his friends in the Lettermen’s Club to get “the cute new girl with the weird first name” elected. “My first-ever foray into political lobbying,” he calls it. Like most of his lobbying efforts since then, it was a success.

When Delaine turned 16, he was allowed to take her out by her conservative parents—but only if it was a double date. They dated on and off through high school and college. Once Emmert left for the UW, Delaine dated other men, including Emmert’s future college roommate, Randy Grab, ’76. “There was no jealousy involved,” Grab now recalls. “After all, I got to sing at their wedding.”

Delaine would later attend the UW, majoring in education but not quite finishing her degree, which she later completed at Central Washington University and Northern Colorado University.

Even though he and his brother were the first members of their family to go to college, Emmert never considered other alternatives. “There never was a doubt; it was always assumed that I would go to college,” he says. “My parents instilled in me the value of education at a very deep level.”

Emmert’s brother Steve decided to attend Washington State University and Emmert helped him move in. “I remember liking the campus a great deal but thinking, ‘Gosh, this is a long way in the country,’ ” he says. Today Steve Emmert is a senior building inspector for the city of Kent and a Cougar fan. “We always tease each other unmercifully over the Apple Cup,” Emmert says.

After graduating from high school in 1971, his friends and cousin went away to school, but Emmert had to stay behind. He attended Green River Community College in Kent for a year and a half instead. “He saw it as a cheaper way of going to college,” Herting recalls. “If you look at his experience at that level, it does give him insight into the whole process of higher education.”

The finances finally worked and in the spring of 1973, Emmert arrived on the UW campus. As the trees bloomed on the Quad that spring, so did his world. “What was wonderful and magical about it was the sense of place and mostly the intellectual awakening that came for me,” he recalls. “It was just so much fun to have your mind opened up by all these fascinating people.”

One of his first encounters was with Civil War historian Thomas Pressly. “He may have been the first real intellectual I had ever spent time with. He’d finish a lecture and students would literally rise to their feet and applaud like it was a performance,” Emmert says.

Although Emmert loved history and literature, he chose political science for his major. “[Political Science Professor] Hugh Bone was wonderful and had a huge impact on my excitement for politics and government. He helped convince me to turn to public administration,” he says.

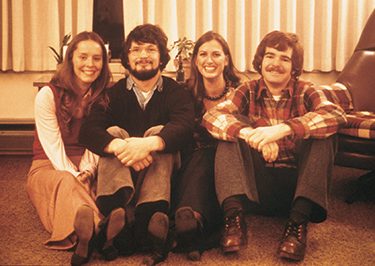

This happy student foursome from the 1970s includes Mark Emmert’s roommate, Jerry Herting, ’75, ’86; and friends who lived in the same apartment complex. Left to right, Marjorie Hames, ’76; Herting; Molly Mitchell Hemingson, ’74; and Emmert. Photo courtesy Jerry Herting.

Emmert roomed with his high school buddy, Jerry Herting, the whole time he was a student. They lived in several apartments before sharing a house in Wallingford with two other roommates from Fife. “Mark was one of the more driven guys at that time. You could tell that he was going to continue on in school,” says Grab, who also lived at the house.

When they weren’t studying, sports was part of their student experience. They played on IMA softball teams and went to Husky football and basketball games. “We were there for Don James’ first year and we were hopeful that something was going to change,” Grab says.

Herting says there were plenty of nights when they would sit down and play guitar (“Mark is a better singer than I am,” he says). Like many other students of that era, there were plenty of nights playing foosball at the Duchess Tavern or talking politics and movies at the Last Exit on Brooklyn coffeehouse.

But hanging over their lives was the war in Vietnam. Like every other 18-year-old male, Emmert was subject to the draft. “Sitting in front of the TV, watching your number pop out, it personalized the experience of the war,” he says of the draft lottery.

Because President Richard Nixon was winding down the draft at that point, even Emmert’s relatively low number of 124 did not get called up. But he had classmates and cousins who went to Vietnam, and one high school acquaintance—Ed Zumwalt—never came back. “You knew people who were getting shot, or serving, or even dying,” he says. Asked if he went through a period of long hair, rock music and anti-war politics, he answers, “Oh yeah. I’m sure my parents were saying, ‘Dear God, please let this phase pass.’ ”

But in addition to school, sports, music and politics, Emmert and his roommates also had jobs. “All of us were pretty much putting ourselves through school,” Grab says. Emmert worked at Autovia, an auto parts store on 47th Street and the Ave.

He had always loved cars and drove a 1965 Ford Mustang in high school, so the job was a good fit. But it also kept him from taking advantage of all that the UW offered. “I always worked. In retrospect, I probably worked too much,” he says. “Were I to go back and do it again, I would do it differently. I would have done the UW more intensely.”

Instead, his intensity was aimed at an English sports car. “I was a sports car nut. I lived and died for my little Austin-Healey,” he admits.

“Mark had a sports car addiction,” adds Herting. Spear recalls many times when they’d go to the old Seattle International Raceway for autocross races. Drivers tried to get the best time while negotiating a twisting course marked out with traffic cones. Emmert was one of the better drivers, says Spear.

“One of my great decisions when I was finishing up at the UW was to go off to graduate school or get serious about racing cars. I’m still not sure I made the right decision.”

Mark Emmert

But there came a time when the passion had to end. “One of my great decisions when I was finishing up at the UW was to go off to graduate school or get serious about racing cars. I’m still not sure I made the right decision,” Emmert jokes.

At first he thought about law school, but decided the subject wasn’t the best fit. His mentors in political science—Hugh Bone and David Paul—suggested a relatively new degree, a master’s in public administration. “The more I looked into it, the more I thought about becoming a city manager. It seemed a great nexus of politics, management and public policy,” Emmert recalls.

“Everybody kept saying the strongest program for what I was looking at was Syracuse University,” he says. Once he was accepted, he realized there was almost no financial aid in the master’s program. “I sold everything I owned, including my beloved Austin-Healey,” he says. “My mom helped put me through school. It was very expensive. Looking back on it, and knowing my parents’ relative income, it must have been a staggering amount of money.”

When he walked in the door at Syracuse’s Maxwell School of Public Affairs, he wanted to work in city government. But it wasn’t long before higher education took over. “A number of faculty members asked me if I ever thought about becoming a professor. To be perfectly honest, it hadn’t crossed my mind, and then it was like a light bulb going on,” he says.

After earning his master’s in just one year, Emmert knew he wanted to come back someday for his Ph.D. but had enough of the student life. So he headed for Riverton, Wyo., where he became director of student aid at Central Wyoming College, one of the state’s seven community colleges. The college had several branches, including one on the nearby Wind River Indian Reservation, where Emmert lived in a trailer.

“Mark is a quick study. He is so good at understanding people, as skilled as anyone I’ve ever worked with.”

Jim Isch

“I was looking for something very, very different from what I’d ever done,” he says. He got his wish. He met great people (“Friends for life,” he says) but he also found poverty, high unemployment, alcoholism and drug abuse. “It was the first time in my life I confronted real deprivation and challenging social environments of that magnitude. Here I was, growing up a middle class kid in safe and sane Fife, and it was a whole different world. I saw people trapped by their social circumstances.

“I learned a lot, I grew up a lot. Prior to that, I thought—like probably a lot of Americans—that anybody who pulls up their socks and works hard can achieve anything. You look at some of those circumstances and you say ‘It’s not that simple,’ ” he explains.

Spear visited his cousin and was struck by the primitive living conditions. “At night you could hear the rat traps going off as they caught something,” Spear says. “The water was so bad, you had to treat it with lye. So the water smelled like lye and it tasted like lye. If you cooked food in it, the food tasted like lye. If you washed clothes in it, you smelled like lye.”

Perhaps it was the isolation that prompted Emmert to finally get serious about his long-term relationship, since it was then that he asked Delaine to marry him. “We had always corresponded and stayed in touch, even when we were really mad at each other. We concluded that we really did love each other and, after all this nonsense, we were soul mates, so we got married,” he says.

At LSU, Delanie and Mark Emmert appeared on stage in the two-person play Love Letters by A.R. Gurney. The sold-out performance was a fund-raiser for LSU, costing $500 per ticket. The Emmerts enjoy all the arts and last October did a reading from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town for a LSU drama class.

In 1976 they had a hometown wedding in their church in Fife and then Emmert brought his new bride back to his trailer in Wyoming. It was not what his wife expected. “We lived there for six months together. We almost had a very short marriage,” he jokes. “One day she told me, ‘I’m going back to school and you are welcome to join me.’ ”

Delaine enrolled in the college of education at Northern Colorado University in Greeley, Colo., and Emmert soon joined her. There and in Alamoso, Colo., where Delaine did her practice teaching, Emmert found jobs as a student counselor or financial aid officer.

When Emmert returned to Syracuse University in 1980, he was a changed person. He had spent 18 months living on the Wind River Indian Reservation, he got married, he helped put his wife through school and he became a father (son Steven was born in 1978). With his wife working to support the family, Emmert blazed through the doctoral program, earning his Ph.D. in 1983-only three years after starting.

Emmert’s scholarly interest is organizational psychology. “One of the notions that fascinated me is how do you hold together organizations. How do you get people committed to and attached to an organization, when that’s not the natural predilection of our species?” he says.

At that time the concept of social biology was entering the social sciences. “It was very controversial. There was some serious science going on and a lot of quackery,” he says. “Social scientists were just beginning to discover that the tabla rasa of behaviorism was maybe not exactly right. Maybe we are living, breathing organisms after all.”

His thesis title sounds dry and academic—“Coevolutionary theory and organizational commitment: an exploratory study in bureaucratic behavior”—but his research was excellent preparation for becoming the leader of a large university.

With his doctorate in 1983, Emmert began what he calls his lap of America, a looping dash across the Midwest, Far West, East and South that would see his academic career spiral upward.

He started as an assistant professor of political science at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, Ill. After two years of teaching public policy and administration courses, he jumped at the chance to move to Boulder, Colo., to join the faculty at the University of Colorado Graduate School of Public Affairs.

It was at Northern Illinois and Colorado that he sharpened his teaching skills. “I loved teaching. The vast majority of my experience has been in seminars and graduate programs. It’s really hard not to like to do that. How can you not like sitting around with smart graduate students talking about the things you love?” he asks.

At Colorado he became a tenured professor and published more than 20 refereed articles in scholarly journals. He also wrote several book chapters and reviews and was an associate editor for one public policy journal. At the same time he conducted research and training for local public agencies, including Denver Public Schools, the City of Aspen and the Colorado Supreme Court.

But it wasn’t long before Emmert caught the eye of the academic leaders at Colorado. His public affairs dean offered him an assistant dean’s post and Emmert couldn’t turn him down. Here was the nexus between politics, management and public policy he had so often talked about.

Academic administration intrigued him, but he needed to know more. He found out about a fellowship sponsored by the American Council on Education, where an up-and-coming faculty member serves as a special assistant to a system leader. So Emmert asked Colorado President Gordon Gee if he’d agree to let him shadow the CU president for a year.

Gee was already an academic legend, having been appointed a university president while still in his 30s. After Colorado he would go on to head Ohio State, Brown and Vanderbilt. “We all but lived together, and living with Gordon is an education,” Emmert recalls. “He is the most energetic person I’ve known. In one year, I got five years of experience.”

“Most people who have been with me on this fellowship take one look at the work and decide to return to the faculty,” says Gee. “But not Mark. He met and exceeded all expectations.”

Gee says the fit with academic administration was near-perfect. “Here he was, a policy guy, and he had all the right kind of educational background and the right kind of instincts.” Soon afterward Gee found an opening at Colorado’s Denver campus and named Emmert associate vice chancellor for academic affairs. In total, Emmert spent seven years at the University of Colorado—the longest stay of his academic career—and still has a personal connection to CU. His daughter, Jennifer, just finished her freshman year at the Boulder campus.

Mark Emmert, center, tries to pull down a support rod in the Berlin Wall as his children, Steve and Jennifer, pose for the camera. Emmert received two Fulbright fellowships to the former East Germany in 1991 and 1994. Photo courtesy Mark Emmert.

In 1992 a call came to join Montana State University as its provost—the chief academic officer. At that time Montana was consolidating all of its public college and universities into two systems—one run by the University of Montana and the other by Montana State. There were plenty of battles in the legislature over where these schools would go.

On top of the turf wars, the resource-based Montana economy was in trouble. “I was there from 1986 to 1994,” recalls Jim Isch, who was vice president for administration and finance when Emmert arrived at Montana State. “We had nine budget periods and had to absorb cuts in eight of those nine budgets.”

Isch recalls his first meeting with Emmert. “He looked young at the time. When you first met Mark, you wondered, ‘Does this guy have the ability to do the job?’ He hardly looked dry behind the ears,” he says.

But Emmert’s style immediately put the campus at ease. “He got up to speed immediately. Mark is a quick study. He is so good at understanding people, as skilled as anyone I’ve ever worked with,” Isch says.

“It was a very tough place to make higher education work,” Emmert says. He had to make several cuts, including closing two departments in the agriculture school. “The agriculture lobby in the state is very strong,” notes Isch. “Mark has the ability to unarm people who come into his office and want to be upset.”

When closing down academic departments, Emmert says, “There is no way to do it without leaving blood on the floor.” It was the first time Emmert’s management style took center stage. He opened up the budgetary process and made MSU’s situation transparent. “We invited everybody to have ideas. But I told everyone it is not acceptable for you to say ‘don’t’ unless you’ve got another option. If you’ve got another option, I want to hear it. I don’t have perfect wisdom,” he says.

In addition to closing and consolidating departments, some staff and non-tenured faculty were laid off. But at the same time, Emmert was able to launch a new engineering research institute, enhance undergraduate education and begin two major construction projects. “We hadn’t had a new building on campus since the 1970s,” Isch recalls. “Mark went out and got federal funding for a new plant sciences building and got a variety of sources to fund a new engineering building.”

“It was a difficult job, but such a wonderful place. We love Bozeman,” says Emmert, who still owns vacation property there. “But the relative wealth of Connecticut was a welcome change.”

A bearded Mark Emmert chats with then President Bill Clinton at a 1995 library dedication at the University of Conneticut. Emmert was the UConn chancelor at the time. On May 21, Emmert hosted another sitting U.S. president as President George W. Bush delivered the 2004 announcement address at LSU. Photo courtesy Peter Morenus, Jr., University of Conneticut.

In 1995, Connecticut’s flagship campus at Storrs needed a new chancellor. Then UConn President Harry Hartley was impressed the moment he met the provost from Montana State. “Sure he was young, but he was also a graduate of the top public affairs school in the country. He stood head and shoulders above the other finalists. He was personable, charming and already dealt with a multi-campus system in Colorado and Montana,” he recalls.

Emmert arrived in Connecticut just as Hartley was pushing a $1 billion, 10-year construction plan through the state government. “We were kind of like the dog that chased a car and finally caught it,” Emmert says. “We got the billion dollars and we didn’t have a facilities master plan. What we had was essentially a laundry list.” Emmert took control, breaking ground on two projects at the top of the list and hiring a firm that put together a comprehensive master plan in 12 months.

On top of the $1 billion building plan, Emmert lobbied for $4 million in state funding for an applied technology research center, upgraded the student experience with a new freshman transition program and a center for undergraduate education, and created an Office of Multi-Cultural Affairs, which boosted faculty and student diversity. The Connecticut Huskies also made their mark in athletics—the women’s basketball team won the national championship in 1995 and the men won in 1999.

“We used to be the second or third choice for students—even those living in Connecticut,” recalls Hartley. “Now everyone wants to come to Connecticut. We’re no longer a regional school, we are a national school.”

But UConn was also a destination for students throughout New England during spring break. Its annual Spring Weekend got wilder and wilder in the late ’90s. After an unruly outbreak in 1997, campus officials thought they had a plan to keep students under control. Instead, in 1998, the weekend ended in a drunken riot with 2,000 students pelting police officers with rocks and bottles, and police responding with pepper spray. Three cars were overturned and one was burned. Rioters caused more than $20,000 in damage to campus property.

In the wake of the riot, UConn punished 81 students, expelling two and slapping six others with a one-year suspension. “That was very difficult,” Emmert says. What was once a spring festival had become almost a “ritual riot” for students across New England. Among those arrested, about two-thirds were not UConn students, he says.

“We worked with student leaders to keep things under control, and the student leaders were terrific, but they weren’t in control either. Unfortunately, nobody was in control,” he adds. The following year UConn had community policing in place and better communication with students. The result: Spring Weekend was much quieter.

The spring riots at UConn sound similar to a Greek Row melee last September at the UW that saw $6,000 in damage and the arrest of eight people, though none of the eight were UW students. Emmert cautions against hasty comparisons. “What worked at Connecticut might be a disaster at UW,” he says. “I don’t know enough to say what the answers are. I’m going to work a lot with our students and the neighbors. We’re not going to shy away from our responsibilities as the 600-pound gorilla in the neighborhood.”

It was at Connecticut that Emmert got his reputation as an institution builder. It was that promise that prompted the leaders at Louisiana State University to lure Emmert to Baton Rouge in 1999 as their new chancellor.

LSU, like the UW, is the state’s flagship research university. Its main campus has 32,000 students, a football stadium that holds 91,000 rabid fans and school colors of purple and gold. But it is not a top-tier public research university. In the last rankings by the National Research Council (regarded within higher education as the most valid poll of academic excellence), almost a third of the UW’s doctoral programs were in the top 10 and almost three-fourths were in the top 25. None of LSU’s doctoral programs were in the top 10 and only two were in the top 25.

LSU Chancellor Mark Emmert congratulates as LSU football player after the Tigers’ 21-14 victory over Oklahoma in the 2004 Sugar Bowl. The win clinched the national championship for LSU in the BCS rankings.

Until 1988 LSU had an open admissions policy for Louisiana high school graduates and wasn’t known for its academic rigor. Two years before Emmert’s arrival, a fraternity pledge died of alcohol poisoning during a hazing ritual, and when the new chancellor stepped into his office, he found that LSU was ranked the No. 1 party school by the Princeton Review test prep service.

LSU alumnus James Carville, the political consultant, best-selling author and Crossfire co-host, says his alma mater was “dispirited” when Emmert arrived in Baton Rouge and that “we weren’t getting what we needed from the Legislature.” Faculty morale was low and even the football team had a losing record.

With the help of faculty, regents, students, lawmakers, staff, parents and community leaders, Emmert started to turn LSU around. He created the LSU Flagship Agenda, aimed at making the university a “nationally competitive” research university. While state support for higher education was dropping in many states, LSU saw a 25 percent increase in state support over his first four years.

At the same time, Emmert was able to fund merit pay increases each year for LSU faculty—a cumulative 22 percent increase over four years, using tuition surcharges, state funding and money reallocated from some departments.

The new chancellor was able to raise about $100 million in new construction revenue from several sources. He conceived of the tuition surcharge—the Academic Excellence Fee—convincing students to accept a 40 percent increase that would decrease class size, open more sections and pay teachers a better salary.

The changes were remarkable. “Having a plan really provided a lot of hope for people,” says LSU Provost Risa Palm. “The atmosphere improved,” adds LSU Faculty Senate President Carruth McGehee. “The faculty pay increases came at a time when many other universities were not enjoying increases due to the economy.”

“The place is entirely different since he took it over,” adds Carville. “It is probably the most improved school in the country.” Even the party school ranking dropped.

Emmert is careful to credit many factors in the turnaround. He notes that during the recent recession, the Louisiana economy fared well compared to most of the country. He says the governor at that time understood the importance of higher education. “The most important piece was getting people to understand why higher education in general, and LSU in particular, must be stronger and better than it was, if it was going to help lead an economic transformation, lead cultural and social development, as well as being the champion of education,” he adds.

“He is absolutely the best boss I have ever had. He’s the most significant reason I was interested in this job. Never once has he disappointed me.”

Nick Saban, LSU football coach

Not that the road through LSU was free of speed bumps. His LSU Flagship Agenda listed 12 academic areas where there was going to be new investment—which created an atmosphere of “haves” and “have-nots” among LSU departments. “What amazes me was how accepted that list is,” says Provost Palm. “Now departments are asking, ‘How can we get on that list?’“

Emmert says his most difficult task was not dealing with discontented faculty or reluctant lawmakers. In the first years of the new century, Baton Rouge was being terrorized by a serial killer. By the fall of 2002 police had traced three deaths to the killer and signs were posted on the LSU campus warning, “Killer on the loose!”

“As female students, we were afraid to walk anywhere by ourselves at night,” recalls Samantha Sieber, editor of the LSU student newspaper. “If we had to walk to our cars by ourselves, we’d call a friend on our cell phones first and talk to them all the way to the car.”

In March 2003, the killer struck the LSU family. The body of 26-year-old LSU doctoral student, Carrie Lynn Yoder, was found in a waterway about 30 miles west of Baton Rouge.

“It was the most miserable thing I have ever had to deal with in my entire life,” Emmert says. “It was horrible. I talked with the families. Consoling a family that has lost a daughter or a spouse and is going through this—I don’t ever want to ever do that again in my life.”

Emmert’s open style came through in the crisis. “He was at the rallies and at the protection forums,” recalls Sieber. She remembers one student complaining about the waiting list to get into personal safety classes. “He told her, ‘I didn’t know about that. You will get into your class.’ And the next day they offered more classes and eliminated the waiting list,” Sieber says.

While some campuses might have tried to explain away the negative publicity, Emmert says he was frank about the problem. “It was very important that the university not try and hide from this. We said, heck yes, this is terrorizing our campus, and here are all the things we are going to do. Did that cause us some image problems? Yeah, I’m sure it did. And I’d do it again the same way, because it was the right thing to do.”

Yoder was the last victim. In May of 2003, Derrick Todd Lee was arrested and charged with her murder. He is currently being tried for another Baton Rouge murder and faces charges in a total of seven killings.

Sieber says it was no surprise that Emmert was so visible during the crisis. “He makes room for students in his life,” she says. “You can find the chancellor walking around campus with his jacket over his shoulder. If he’s met you before, even if he can’t remember your name, he’ll remember your face and start up a conversation with you.”

But some LSU professors have been critical about the amount of time Emmert spends on external affairs. “Chancellor Emmert has largely been occupied with relations between the university and the legislature and the governor and the community. He has been a representative to the outside first. That’s his primary role,” says Faculty Senate President McGehee. “He hasn’t been around much in the campus and in the colleges.”

Some faculty attacked Emmert’s salary when their own pay lagged far behind their peers. In the spring of 2002, when the University of South Carolina tried to lure him away, LSU’s trustees matched the offer, giving Emmert a 72 percent pay increase. His $490,000 salary plus annual $100,000 bonus made him one of the highest paid public university leaders in the nation. (At the UW Emmert will make $470,000 plus gets a $120,000 annual bonus if he stays for five years.)

One professor complained that the only places where LSU ranks No. 1 in the country were in the salaries of its football coach and its chancellor. The Faculty Senate voted 23 to 11 to condemn the increase.

“That vote was not a personal criticism of Chancellor Emmert,” says McGehee. “It was a criticism of those who made the decision. The faculty was quite glad to have him stay.”

What was lost in the salary dispute was that Emmert had used the South Carolina offer to get further commitments from the governor and lawmakers for Louisiana’s colleges and universities. Gov. Mike Foster issued a statement that read in part, “All the talk about rolling back taxes while LSU is last in the SEC in investment mystifies me. We are going to have the best and the brightest and lead the future—or be dead last forever and be known for our mediocrity.”

Even with his record-breaking salary, his pay was far behind LSU Football Coach Nick Saban, whom he had recruited from Michigan State with a $1.2 million pay package in 2000. It is unusual for a university president to get deeply involved in the hiring of a football coach, but the LSU athletic director was retiring at the time, so Emmert stepped in after the Tigers stumbled to a 3-8 season under then coach Gerry Dinardo.

“He was very much personally involved in that,” LSU Professor Kenneth Carpenter, chair of the LSU athletic council, told the press. “Had that not worked out, had Saban not been successful, there would have been a lot of criticism. But now it looks like he was the smartest guy in the world.” Under Saban, LSU had an 11-1 record last season and shared the 2003 national championship, the team’s first since 1958.

Saban is a big fan of Emmert’s. When he heard that the UW was trying to hire him, the football coach told the Baton Rouge newspaper, “He is absolutely the best boss I have ever had. He’s the most significant reason I was interested in this job. Never once has he disappointed me.”

Emmert took advantage of the national championship spotlight to write an op-ed piece in the New York Times touting LSU’s academic rise. Back on campus, he told anyone who would listen that “If we can be number one in football, we can be number one in physics.”

Yet his emphasis on sports has its detractors. Some UW professors are concerned that Emmert may have his priorities in the wrong place, that he is too much of a “sports guy.”

“Anyone who thinks that is just plain stupid. They ought to go jump into Puget Sound. It’s silly,” says LSU alumnus Carville. “There is no sense at all that that is the case.”

Retired UConn President Hartley is more diplomatic, but makes the same point. “Mark understands the balance between academics and athletics. Primarily he is an academic scholar.”

With his strong involvement in athletics, Emmert realizes some may get the wrong impression. “It looks like, ‘Oh gosh, Emmert loves athletics.’ When in fact, I like sports, but it is a vehicle for me for promoting the university,” he explains.

It was at Connecticut that Emmert got his reputation as an institution builder. It was that promise that prompted the leaders at Louisiana State University to lure Emmert to Baton Rouge in 1999 as their new chancellor.

“Those professors who say I’m not focused enough on academics don’t see that that’s what I do all day long,” he adds. “I always get a kick out of faculty who seem surprised when I stand up and give a talk on curricular reform or the value of the tenure process. They seem amazed that we’re academics at heart. That’s what I do all day long. That’s why I work in this enterprise.”

But there is no doubt that Emmert’s record with sports was a factor in the regents’ choice. With the UW program rocked by gambling violations by its former football coach and charges of illegal drug dispensing by a former team doctor, Emmert’s reputation for keeping a watchful eye on athletics-and running a clean program-was a plus.

Jim Isch, his Montana State colleague, is now the NCAA’s vice president for administration and finance. He says Emmert’s reputation is impeccable. “Our folks have a great deal of respect for him,” Isch says.

When there was a minor infraction at LSU involving tutors giving too much help to student-athletes, Emmert asked faculty and staff to come forward with any information about academic misconduct. He also invested an extra $1 million in the academic support program for athletes and moved its reporting lines to the provost’s office. “The position he took at LSU, that gave him a lot of respect,” says Isch.

Emmert will find out how much clout he has on June 11, when—even before he officially becomes UW president—he will be part of the UW team that presents its case to the NCAA over the recent gambling and recruiting violations.

Emmert once said that success for LSU football was “essential” for the overall success of that university. At Washington, he takes a slightly different approach. “We don’t have to win football championships to be a great university at the University of Washington, but we need to have the programs reflect our values and reflect what we want people to see about the University of Washington. If they think the sports program is in disarray, they think the University is in disarray,” he says.

Asked if he agreed with one newspaper columnist who said there was a “crisis of the soul” at the UW, Emmert replies, “The athletic enterprise is not the soul of the University. The faculty is the soul of the University. That has a great integrity. That soul is in very good shape.”

While hiring a new athletic director will be one of his first steps as the new UW president, Emmert says his top priority is “to learn the University of Washington all over again. Sure, I know the place, I know the buildings, but I don’t know many of the faces that reside in those buildings. I’m going to have to go on a crash course of ‘U-Dub 101.’

“I’m going to go around listening to a lot of folks, everywhere I can.”

When he reaches out to the campus and community, there will be a lot of curiosity over Emmert’s style as well as his substance. “He’s not a back-slapping kind of guy,” says Carville, “but he’s very smooth. In Louisiana, he knew how to get into the system right way. As soon as you met him, you knew this was the guy for LSU. You had confidence in him.”

Vanderbilt University President Gee says, “Mark has a great sense of humor. He is also a fine decision maker. He understands at the end of the day the buck stops at his desk.”

His cousin, Frank Spear, also touches on this Harry Truman-like quality. “Mark has incredible integrity. He is not afraid to buck the trends if he believes another direction is more appropriate.”

When they voted on the new president, the regents keyed in on his decision-making abilities and academic leadership. Regent Shelly Yapp, who was on the search committee, said Emmert was a leader who could make institutions “reach beyond where they thought they could go for academic excellence.” Regent Connie Proctor added, “He loves this institution, and that can only make him a better president.”

For Emmert, becoming president of the University of Washington is the ultimate homecoming. “This is such a great honor for me,” he says. “I can’t imagine being at a better university than this. This is an extraordinary academic institution. This is my home. This is my last stop in that lap of America.”

Hot topics: Emmert on the issues

The future of public higher education

“I hope that we never, ever move away from the great tradition of public higher education in America. It is one of the great strengths of this nation. I am obviously one of the beneficiaries of it, as are millions of other people. Public higher education has been, for a century and a half, the social, cultural and economic ladder of our society. If we move to a quasi-public or quasi-privatized model, we’d better be sure of what we’re doing-what its impact is going to be on our society.”

The impact of rising tuition

“Tuition will continue to rise. We need to make sure that we have appropriate financial aid structures in place that will always allow people to attend the University of Washington regardless of their financial status.”

Reforming undergraduate education

“We will be constantly, constantly improving the undergraduate experience at the UW. The real trick is to provide students with as many small-scale experiences as they can, so that they can break down that great big campus into discrete units. Their educational experience and their social experience become more personal.”

Keeping the UW diverse

“Diversity is critical to the educational experience for all students. We continue to be the ladder to social, educational and economic success for all of our citizens. That means we have to work at making the campus a welcoming and supportive environment for all people. I’m going to be aggressive about that. It isn’t easy. At LSU, we had a campus that was segregated until the 1960s. There are enormous challenges here. The environment at Washington is quite a bit different in that context. The solutions have to fit the local culture and context.”

The future of UW Tacoma and UW Bothell

“This is one of the most important questions facing the University of Washington. We want these campuses to grow and flourish. Exactly what that model looks like has yet to be worked out.”

Reaction to the $35 million paid for over-billing government health plans

“My understanding is that the University has done all it can to respond appropriately. It has obviously been a big story. All we can do now is fix it and move on.”

The place of sports on a college campus

“I don’t know of a single university president, if you could start all over again, who would recreate the model of collegiate sports the way it is today. I surely wouldn’t. But the reality is that the University of Washington is not going to stop playing football any time soon. And it’s not going to get rid of crew. And it’s not going to stop playing women’s basketball. They are going to continue to be important in the social and cultural lives of the people of the UW. I’m a hard core pragmatist about intercollegiate sports. We’d better be leaders in the way we conduct business. We’d better be leaders in whatever the reform movements are. We’d better be leaders in the way our program succeeds—and I don’t mean win-loss records. We’d better be leaders in the way we win games, in the way everybody behaves, in our academic success, in our graduation rates, in everything that would make our faculty and students and staff and alumni proud.”