In the hit 1978 movie Animal House, members of the fictional Delta Tau Chi fraternity engaged in a variety of pranks—from a drunken toga party to leaving a dead horse in the dean’s office—that might be considered tacky but inflicted no long-term harm.

In the early hours of Sunday, Sept. 27, 1992, a beer bottle thrown during a Greek Row fracas between a few members of Phi Delta Theta fraternity and a group of Husky football players cost UW student Jennifer Wen her eye. A witness to the accident described the sound of the bottle striking Wen’s face as somewhat like a bottle shattering against a brick wall.

Seattle police have been unable to identify the individual who, among the several bottle throwers that night, heaved the missile that struck Wen. No criminal charges have been filed in the case, though Wen’s attorney has filed a lawsuit against the fraternity. But her tragedy is not without consequences. It initiated a new era in which campus officials expect to exert far greater influence over the 4,000 students who reside in the UW’s Greek system.

University officials will soon require representatives from each fraternity and sorority to sign a separate contract with the institution as a condition for remaining part of the UW community. Until now, the University has extended an implicit, blanket recognition to the Greek system as a whole.

The state Attorney General’s office is responsible for drawing up contract language, which will then be discussed with students and others. “My hope is that … no later than mid-summer we would have a finished product,” says Ernest Morris, vice president for student affairs.

“You must understand that you're going to be held accountable for your actions and you might as well start now because that's what life's all about—accountability.”

Ernest Morris, vice president for student affairs

Whatever the final language, the agreements are expected to set rules of conduct and establish sanctions for breaking those rules. “I think what we’re seeing is an effort to make tangible something we talk about a lot in higher education . … Namely, that you must understand that you’re going to be held accountable for your actions and you might as well start now because that’s what life’s all about—accountability,” says Morris.

The contracts are the centerpiece of a package of recommendations for the control of Greek row behavior, particularly excessive drinking and underage drinking, hammered out by a 19-member task force appointed by President William P. Gerberding after the Wen incident.

The new requirements modify the UW’s long-held position that campus officials have little authority over the Greek system because the houses are privately owned and located off campus.

“It’s a way of trying to negotiate a rather murky legal area because those are privately owned and operated facilities and we can’t pretend that we can control what goes on out there in the same way we can control institution property,” says Morris who will sign the agreements on behalf of the UW.

About 60 members of Phi Gamma Delta raised $27,000 for cancer research by running the 1993 Rose Bowl game ball from Seattle to Pasadena. Three runners are, left to right, Shael Anderson, josh Mathis and Pat Tucker. Photo by Saul Bromberger.

The legalities are not just murky but also controversial, say some students and alumni involved with the Greek system. Many agree that change is clue. The state legislature passed a bill that almost exactly matches the UW plan. It was sent to the governor for signing in May. But some question whether the UW’s plan is fair or even feasible.

Fair or not, the proposed change comes not a moment too soon for long-suffering Greek Row neighbors.

“Four thousand long-term transients affect our quality of life,” says Gretchen Sorenson, a neighbor who represented the community on the task force. Sorenson has had first-hand experience with student pranks. One clay she discovered that her rhododendrons had been pulled up and replanted in the yard of a fraternity house to make it presentable for an upcoming parents’ night.

Sorenson ultimately received a check from the offending chapter but no apology and no indication that any punishment had been imposed. “It’s a menace,” she says of behavior in the Greek neighborhood. “It’s a pity that a young woman had to sacrifice an eye to get the University’s attention.”

So who are they, these heretofore self-governing or, some would say, ungoverned UW Greeks? Are they the fictional youthful pranksters of Animal House or a sometime threat to individual and community safety, as in the case of Jennifer Wen? Or are they, as many people associated with the system are quick to note, a source of community service and a cradle where the leaders of tomorrow learn their leadership skills?

“There are a few houses who have made it nearly a career to inflict themselves on the community.”

Seattle Police Capt. Doug Dills

They certainly are leaders in later life. According to statistics provided by the UW Interfraternity Council (IFC), 85 percent of Fortune 500 executives belong to a fraternity. Fraternity men head 43 of the nation’s 50 largest corporations. More than three quarters of all U.S. representatives and senators belong to a fraternity.

“When you consider at least the pronouncements that are made about what the system stands for—the promotion of brotherhood, sisterhood, the forging of lifelong relationships, the opportunities to develop leadership skills and interpersonal skills—I think, in the main, those objectives are achieved by many of the organizations,” says Morris who chaired the task force. “I think the problem, however, comes when an organization loses sight of its larger purpose and when drinking and partying and engaging in antisocial behavior become more the guiding principles.”

Responsibility for sorting out those problems often falls to the Seattle police, who note that the difficulties are not evenly distributed throughout the system. “The Greek system is a significant problem but it needs to be understood that … there are a few houses who have made it nearly a career to inflict themselves on the community,” says Capt. Doug Dills of Seattle’s North Precinct and a task force member.

One fraternity is so troublesome that Seattle police have gathered evidence to support closing it under Seattle’s public nuisance abatement law. If they do so, it will be somewhat like closing a crack house, Dills explains. For the moment, police have halted the process to give the organization a chance to clean up its own behavior.

In a March, 1992 newspaper report, seven months before the Wen incident, Dills identified 10 fraternities that “still need some work.” They are, in alphabetical order, Alpha Delta Phi, Alpha Sigma Phi, Chi Psi, Delta Chi, Lambda Chi Alpha, Phi Delta Theta, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Sigma Phi Epsilon, Theta Chi, and Theta Delta Chi. Dills confirms that the list hasn’t changed in the intervening months.

Complaints to police usually focus on excessive noise, destruction of landscaping, fighting, public display of firearms, or urinating in neighboring yards. “The list goes on ad nauseam,” Dills says. Neighbors of the Greek system also mention speeding, drunken driving, bit and run driving, and the use of sling shots made from surgical tubing.

Complaints to Seattle police have dropped significantly since the Wen tragedy, Dills notes. So has the number of Greek system parties, he adds.

When police know about a party in advance, they often institute an “emphasis presence,” putting officers in the neighborhood early enough to keep things from getting out of control. But they must work within certain limitations. Unlike many communities, Seattle’s ordinances do not authorize police to arrest a minor they find in possession of alcohol. “They can be 15 years old but all we can do is issue a citation,” Dills laments. ”Just a ticket, it’s not bookable.”

Officers who answer calls are often met with a “you can’t do this attitude,” Dills says. They also suffer abusive language and sometimes flying rocks. Twice within the past year officers have been urinated upon by men standing in upstairs windows of fraternity houses, he adds. Arrests were made in both cases.

“It's a society-wide thing. We get singled out because we're a lovely media target.”

Chris Sherwin, 1993-94 Interfraternity Council president

While fraternity-related calls are usually complaints, calls to sorority houses (where alcohol is prohibited) generally involve “victim” instances such as break-ins, assaults, peeping Toms, stalking behavior, etc.

Police, neighbors, UW officials and the students themselves agree that alcohol is a big part of the problem. But excessive drinking also abounds in residence halls and student apartments, notes UW student Chris Sherwin, the 1993-94 Interfraternity Council president. “It’s a society-wide thing. We get singled out because we’re a lovely media target,” Sherwin says.

Sherwin also points out that Greeks do many things in a “wholehearted” fashion. “We study our butts off, we work hard, we play hard,” he observes. And that “play” doesn’t necessarily involve alcohol. “When finals are over I can act goofy but not be drunk.”

On or off college campuses, the highest incidence of drinking in the United States happens between the ages of 16 and 24, says G. Alan Marlatt, UW psychology professor and director of the Addictive Behavior Research Center. Men are more likely to drink than women and Greek houses with “better” reputations for social activities, sports and even academics are likely to have more drinking going on than those that are less sought after.

Thanks to their high school experience, students are often veteran drinkers before they arrive on campus.

“That’s the biggest change I’ve seen since I graduated,” observes Leonard “Banger” Smith, ’82. Smith is a former alumni advisor to Phi Delta Theta.

But even experienced high school drinkers show a big increase in alcohol consumption during their freshman year in college, Marlatt says. Then they enter what he calls a “maturing out pattern” where the level of drinking falls as the student moves toward senior year.

A 1991 survey of 3,000 UW students revealed that 71 percent of UW undergraduates consume alcohol. Fraternity and sorority members reported much higher alcohol use than their dormitory or commuter counterparts. Among underage students in the Greek system, 36 perc cent reported that they consume four or more drinks on a typical weekend evening. Only 14 percent of residence hall students reported similar consumption. Among Greek row residents between 21 and 25 years of age, 45 percent typically consume four or more drinks on a weekend evening. That compares to 15 percent for the next highest group, students living together in off-campus houses or apartments.

About 20 percent of the Greeks under age 21 identified themselves as non-drinkers.

Marlatt is not surprised that young men organized into fraternities are at high risk. “They live, work, study together,” he observes. “Fraternities involve social bonding … that’s why people like them.” The fraternity environment also imposes implicit norms of behavior that are hard for individuals to resist.

But fraternity social bonding has a plus side, notes Smith, who enrolled at the UW the year Animal House was released. Smith acknowledges that his concentration on “fun” left him with a first-quarter G.P.A. of 1.7. But older fraternity brothers, and a trio of 50-something alumni he calls “the three wise men,” quickly demanded that he shape up. He did.

Whatever the Greeks’ drinking behavior, sororities, at least, don’t seem to suffer academically. The all-sorority G.P.A. for fall quarter 1992 was 3.15, according to Panhellenic advisor Helen Becker. The campus-wide undergraduate G.P.A. for that quarter was 3.15. Fraternity members achieved a 2.96 grade point average during fall quarter 1992, says John Underwood, a sophomore and executive assistant to the IFC.

“It's like a college within a college. To this day I have 15 best friends I see once a week.”

Leonard "Banger" Smith, '82

Beyond academics, the Greek system also offers a social support structure within a huge, sometimes cold institution. “You know everyone in the Greek system,” says Smith, the former fraternity adviser. “It’s like a college within a college. To this day I have 15 best friends I see once a week.”

Greek life also inculcates a sense of community responsibility and a lifelong pattern of “strong volunteerism,” Smith adds. During his years on campus, for example, Phi Delta Theta collected 3,500 pounds of food for Northwest Harvest and ran a dance marathon to benefit the Special Olympics. Members of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity raised $27,000 for the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center by running the 1993 Rose Bowl game ball from Seattle to Pasadena. For the past 14 years, members of Kappa Sigma at the UW and WSU have run the Apple Cup game ball across the state. The 1992 run raised upwards of $30,000 for the American Cancer Society.

Sorority philanthropy includes sponsorship of fundraising “Mr. Greek” and “Miss Greek” contests. The annual spring Greek Week generates thousands of philanthropic dollars, primarily from the sale of T-shirts.

Good works and adult accomplishment notwithstanding, achieving consistent leadership and what Morris calls an “institutional memory” among a constantly changing student population is an overarching problem.

Morris applauds Panhellenic and the IFC for some of their policies and regulations. The IFC party policy, for example, requires that social events be registered in advance, identification is required to gain entrance to parties, alcohol containers may not be taken out of a party and parties may not spill over into the street. Kegs or other forms of bulk alcohol are banned and alcohol cannot be purchased with fraternity funds. Parties are either catered or members or guests provide their own beverages—BYOB. “Dry rush” policy prohibits consumption of alcohol by a rush guest at house-sponsored functions. IFC penalties begin with a $250 fine and grow to automatic social probation for a third offense.

The rub comes with enforcement. “We have asked students to carry out enforcement activity and often times they simply lack the capacity to do that,” says Morris. “They are, after all, peers of the individuals they are trying to police.”

Sororities, at least, receive significant guidance from the top. The National Panhellenic Conference has established rules which members must abide by. UW sororities began banning alcohol in the mid-1980s, says Becker. By 1989 all national organizations had prohibited alcohol in sorority houses and even in cars belonging to sorority members. Furthermore, each sorority must have a live-in house director.

The National Interfraternity Council doesn’t match National Panhellenic’s supervision. According to IFC Advisor Gary Ausman, fraternities have a national executive association but its policy statements are recommendations rather than rules.

The terms of the new UW contracts are rules, says Student Affairs VP Morris. And they come complete with clearly established sanctions. He expects them to work and is confident that UW officials will enjoy cooperation at all levels. “It’s early, but the naysayers ought to be careful,” he reflected when interviewed this spring.

“We’re not coming into this with the view that we’re going to have ongoing friction or disputes.”

The contract terms set forth by the task force require, among other things, that houses give University officials advance notice of parties. When alcohol is to be served, Greek organizations must obtain banquet permits through the Washington State Liquor Control Board. That gives Liquor Control Board enforcement officers and Seattle police the right to enter a house and observe what is happening there, says Dills. Furthermore, each house will be required to identify persons who police or others can contact 24 hours a day.

The new University involvement is not a return to the “in loco parentis” responsibility institutions once assumed, Morris notes. But to be on the safe side, house corporation boards will be required to extend their liability insurance to include protection for the University.

“Do you really think they're going to sign an agreement to be 'narcs?'”

Doug Luetjen, '80

A key, and controversial, provision of the proposed contracts holds chapters accountable for the conduct of individual members and their guests. When rules are broken, house leaders and alumni will be expected to take disciplinary action and to report those actions to University officials.

“If you aren’t policing yourselves, if you aren’t holding individuals responsible for abiding by the rules, then we will hold the organization accountable for failing to do what the contract calls for,” says Morris.

That puts too much burden on the students, argues Doug Luetjen, ’80, an attorney and a member of the Sigma Chi house corporation board as well as the board of trustees of Sigma Chi International. Reporting infractions to the officials of a state institution is akin to reporting the behavior to police, says Luetjen “Do you really think they’re going to sign an agreement to be ‘narcs?'” he asks. “Is it enforceable?”

Yes, Morris believes, but he’s looking for a teamwork approach: “It is not our intent to be heavy handed managers of the agreements.”

Morris offers the example of a hypothetical repeat of the rhododendron heist. If the culprit organization can be identified and the evidence substantiates the charge, the chapter will have an opportunity to impose an appropriate penalty, says Morris. “Maybe some community service, restitution, maybe an apology.” Failure to act, or inadequate action, will bring sanctions from campus. Under proposed contract terms they can range from a reprimand to fines, probation, and ultimate loss of UW recognition.

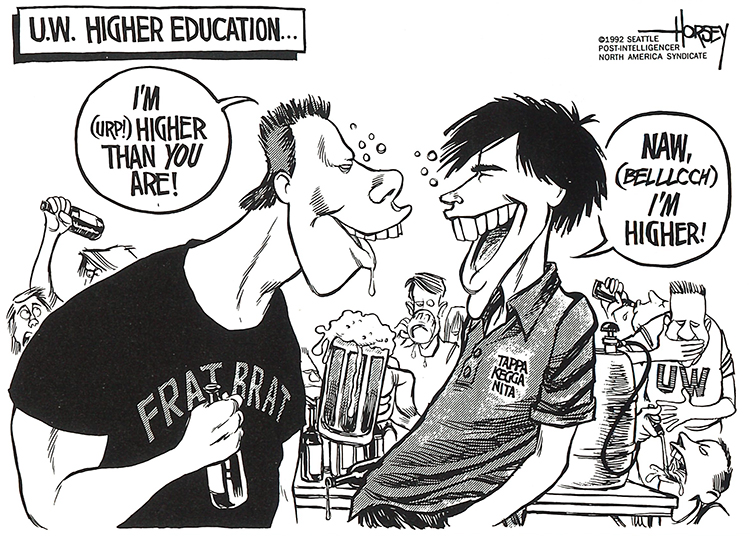

Cartoon by David Horsey, ’76. Courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer

A last resort action would be withdrawing University recognition of the offending chapter. Morris and members of the task force believe that without this “recognition” the chapter would very likely be closed by its national organization.

Not necessarily, counters Sigma Chi’s Luetjen. “That used to be true, but about five years ago they changed that.” The national policy change came after some colleges and universities, primarily private institutions, began imposing regulations that the nationals deemed unacceptable, he explains. These included such things as banning single-sex fraternities or ordering an end to the traditional one-quarter or one-semester pledge period. Today, a national organization may close a chapter for bad behavior but not necessarily in response to political pressure, he adds.

But that doesn’t mean national organizations wouldn’t take UW action seriously, Luetjen adds. “They’d be out here in a heartbeat,” he says. At least at Sigma Chi, alumni representatives would “interview every member offending chapter. Morris and members of the task force believe that without this “recognition” the chapter would very likely be closed by its national organization.

Morris acknowledges that the task force received “mixed signals” about whether withdrawing official recognition could really close a house. “I cannot say to you that all 48 or 49 nationals would respond to us in a particular way,” he says. “I can say to you, however, that if we withdraw recognition and communicate with the national—and keep in mind that there will be prior communication before we reach that point—I would be very surprised if we can’t get the wholehearted cooperation of the people at the national level.”

What about a house that refuses to sign?

“I guess, by implication, if you don’t sign you don’t have institutional recognition,” says Morris. “We’ll make it very clear that the organization ceases to exist in terms of the institution’s view of it.”

IFC’s Sherwin predicts that student and alumni leaders in many houses, including his own Delta Tau Delta, would hesitate to sign agreements as stringent as the task force proposed. “These are not steps,” he says of the new rules. “These are huge jumps.”

Luetjen, who prefers to call the proposed contracts “relationship statements,” says he would hesitate to sign on behalf of Sigma Chi if some of the currently proposed provisions—such as collective responsibility and the requirement to report infractions—are included in the final language. He’s hoping for compromise language that everyone can live with because he’s convinced that signed “relationship statements,” even with language less stringent than that originally proposed, would give the University an effective new level of authority.

According to Sherwin, the major result of losing official recognition would be loss of access to University-provided lists of incoming students, to whom rush material is mailed. Luetjen has another concern—an unsigned house, cut off from institutional recognition, might decide to operate free of any rules including the existing IFC requirements.

Luetjen, Sherwin, Morris and others stress stronger alumni involvement including forging a good working partnership between the IFC and the newly formed University of Washington Alumni Interfraternity Council of which Luetjen is a member.

Established only weeks after the Wen accident, the council plans to hire a full-time “watchdog” over the entire system financed by the fraternities themselves and, hopefully, based in an on-campus office. The new group has already established a “hot line” (526-AIFC) to open lines of communication with the community.

“I can only see good coming from it (the new rules) as long as alumni take responsibility,” says neighborhood representative Sorenson.

“But I think, personally, that it’s going to take a chapter or two being shut down before it really sinks in,” adds University Community Council President Sue Fleming.

Morris is more positive about the future. “We have a clear consensus among members of the University community, the Greek community and the broader community that we have to do something to address these problems,” says Morris. “We’re positioned nicely, I think, to do what needs to be done.”

At top: Members of Sigma Alpha Epsilon pose before their front door. Left to right are Shawn Nyman, Brian Johnson, Tim Cook, Shane Flock, Mark Yang and Brandon Marsh. Photo by Mary Levin.