Editor’s note: Curtis Ebbesmeyer, ’73, holds a curious distinction: he is the world’s leading authority on flotsam. Ebbesmeyer studies ocean currents by tracking the movement of drifting things-from icebergs to message bottles to a flotilla of rubber ducks. In this essay, adapted from Flotsametrics, a forthcoming memoir he co-wrote with journalist Eric Scigliano, Ebbesmeyer recalls the event that first turned him on to flotsam: the Great Sneaker Spill of 1990.

In the wee hours of May 27, 1990, midway between Seoul and Seattle, the freighter Hansa Carrier met a sudden storm and, as freighters often do, lost some of the cargo lashed high atop her deck. Twenty-one steel containers, each 40 feet long, tore loose and plunged into the North Pacific. Five of those containers held high-priced Nike sports shoes bound for the basketball courts and city streets of America. One sank to the sea floor. Four broke open, spilling 61,280 shoes into the sea — and into the vast stream of flotsam, containing everything from sex toys to computer monitors, that is released each year by up to 10,000 overturned shipping containers.

One year later, in early June 1991, I stopped by my parents’ house in Seattle, as I did every week or two for lunch and the latest news. My mother, who loved serving as my personal clipping service, had extracted a wire story from the local paper. It reported a strange phenomenon: Hundreds of Nike sneakers, brand-new save for some seaweed and barnacles, were washing up along the Pacific coasts of British Columbia, Washington and, especially, Oregon, Nike’s home state. A lively market had developed; beach dwellers held swap meets to assemble matching pairs of the remarkably wearable shoes, laundered and bleached to remove the sea’s traces. The details as to how they’d gotten there were sketchy, verging on nonexistent, and that piqued my mother’s curiosity. “Isn’t this the sort of thing you study?” she asked, assuming as ever that her son the oceanographer knew everything about the sea. “I’ll look into it,” I said.

I started looking and never stopped. Seventeen years and many thousands of shoes, bath toys, hockey gloves, human corpses, ancient treasures and other floating objects later, I’m still looking.

Objects like these have been falling into the sea and washing up on the shores since the dawn of navigation — for billions of years longer, if you count driftwood, volcanic pumice and all the other natural materials that float upon the waves. Ordinarily, flotsam is soon lost to human memory. The Great Sneaker Spill would have proved one more curiosity in the annals of beachcombing if my mother hadn’t asked her question, and if I hadn’t been ready to see the research doors that it opened.

***

Like an oceanic gumshoe, I set about tracking down the beached sneakers. When I ask shippers about flotsam washing up from their container spills, 95 percent stonewall. “We are not aware of any lost merchandise,” goes the standard answer. I could never find out what was in the other 16 containers that washed off the Hansa Carrier that day. But Nike’s transportation department was refreshingly open about this spill. Its staff provided the date, latitude and longitude and their container load plan, listing each container’s contents down to the last shoe. Unlike many other footwear manufacturers, Nike stamps a simple identification number, a “purchase order ID” (POID), on each of its shoes. It tracks its products so meticulously that it can trace a single shoe to its mother container.

With the information Nike provided, I could determine conclusively whether any shoe that washed up had fallen off the Hansa. The first beachcombers’ reports of sneakers washing up — ”forerunners,” as one reporter called them-were equally specific. I had something that’s very rare with spontaneous flotsam (as opposed to determinate drift markers): both point A, when and where an object starts to drift, and point B, when and where it washes up.

With this data in hand, I thought of OSCURS, the Ocean Surface Current Simulator program that my fellow UW graduate Jim Ingraham, ’70, had developed at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to calculate the effects of ocean currents on salmon migration. I wondered if OSCURS would work as well with inanimate drifters as it did with swimming fish; subtract the fish’s swim speed and you should have flotsam. In the decades since grad school, Jim and I had gone our separate ways, but the sneaker spill rekindled our friendship. I called him, and he was glad to help. I decided to stage a blind test of OSCURS. I gave Jim only point A, the Hansa spill, and asked if he could calculate point B, when and where the shoes would wash up. “I’ll fax back the answer in an hour,” he replied.

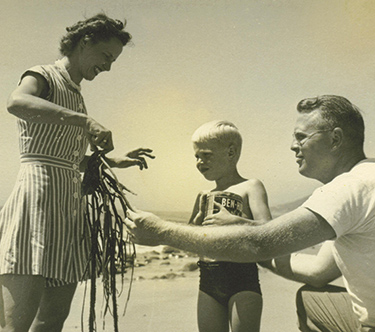

Budding oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer, age 4, learns about seaweed from his parents at Zuma Beach, California.

OSCURS homed in like a carrier pigeon, making direct hits on the earliest point B’s — November and December 1990 on the Washington coast and January and February 1991 on Vancouver Island — where the first sneakers washed up. Jim and I needed more data — the dates and locations of other wash-ups. We began seeking out beachcombers in Oregon and asking if they’d spotted any Nikes, but it was a slow, laborious process. Then we hit the jackpot: One beachcomber directed me to Steve McLeod, a painter in the easygoing resort town of Cannon Beach. Steve is a classic starving artist; he’d won some recognition and big commissions but refused to play the corporate game, preferring to follow his muse and eke out what living he could. He’s also a dedicated beachcomber, which may nurture his muse and certainly boosted his living on this occasion.

Twenty years earlier, as if by premonition, Steve had painted a picture of two gigantic hiking boots hovering over an imaginary beach. When he started finding beached Nikes, a light went on. This was the heyday of sneaker chic, when newspapers feasted on stories about inner-city kids shooting each other for their Air Jordans. Scrape off the barnacles, toss the washed-up Nikes in the washer, add a little bleach, and they looked and felt like new. Steve became a mail-order matchmaker for hundreds of people up and down the coast who’d found mismatched sneakers and wanted mates. When I visited his loft in Cannon Beach, it was filled with two-by-four racks covered with drying sneakers. He sold them on the street, along with his usual trinkets, for $30 each, and took in $1,300.

Better yet, Steve collected even more data than he did sneakers. He had notes on where and when 1,600 shoes had washed up; without him, I might have collected only a third or half as many reports.

Media coverage, swap meets and Steve’s diligence had proven nearly as effective as bottled pleas at eliciting responses from finders. It was solid data, good science. And it was the beginning of a flotsam-monitoring network that now circles the globe — thousands of sharp-eyed field monitors, volunteers in the search for telltale flotsam and indicator jetsam.

***

Even after drifting for three years in corrosive salt water, the shoes remained surprisingly supple and wearable; teenagers can do much more damage to them in one year than the sea did in three. Like seabirds, the sneakers easily rode out storms. I studied their floatability up close, in a hotel spa. Once they became saturated, the sneakers floated upside down, their soles even with the water surface; the high tops of my size-12 Flights cut the water below like the keels of sailing ships, their laces twirling like a jellyfish’s tentacles. At sea, these tough soles would protect the softer fabric from biting birds and bleaching sun. And, we confirmed with each beached sneaker, nothing grew on the soles. Foiling barnacles is no mean trick. Perhaps Nike could supply antifouling coating for ships’ bottoms.

Even today, I get a warm reception at Nike headquarters, where I’m called the “ocean doctor” and invited to speak now and then on shipping, flotsam and the sea. That’s not surprising, considering all the unexpected good publicity Nike reaped from the follow-up to the Hansa Carrier spill. Its shoes’ durability at sea impressed everyone. “Ten Nike marketing managers could huddle for a week and not come up with a better metaphor for the company’s mission-to get Nikes, with near-biblical image making and Yankee dispatch, into the hands of everyone on the planet,” Bruce Grierson wrote in Canada’s Saturday Night magazine seven years later. “It’s tempting to think the whole thing was planned.”

Over the years, many people have asked in all seriousness if I masterminded the Great Sneaker Spill. No, I respond. It’s just the inevitable result of shipping billions of shoes across the sea each year. In fact, Nike has always refrained from exploiting this potential marketing bonanza. When asked why, one company manager replied, “Floating on the water is not a sports attribute we wish to endorse.”

OSCURS proved so accurate at describing and forecasting the current-borne sneakers’ movements that we published the results in EOS, the leading oceanography journal, which goes out to some 30,000 scientists worldwide. That triggered a new tsunami of attention from both the popular media and the oceanographic community. Everyone from the National Enquirer to National Public Radio ran with the floating sneakers. The headlines were soaked in puns: “Afoot on the Sea,” “Footloose Sea,” “Sole Travel,” “Sole Survivors,” “Lost Soles Searching the Currents,” “Not a Sole Was Saved,” “Soles Lost at Sea Sneak up on Beaches.” “Running water” took on a whole new meaning. David Letterman announced his sixth-best reason to join the navy: “If you find a Nike sneaker floating on the water, it is yours.”

But the story was more than just a source of puns and punch lines. It had real implications for the study of the world’s oceans. Building on the sneaker research, I would eventually use flotsam to calculate, for the first time, the orbits of the 11 oceanic gyres — the giant, circular currents that are, after the oceans and the continents, the earth’s largest geographical features. I know that if my mother had lived to see what her curiosity set in motion, she would be happy.

Best of all, the sneaker study had a conspicuous and, I like to think, lasting effect on oceanographic education. At least half a dozen books recount it, and I still get letters from teachers asking me to help shape their syllabuses. It’s deeply gratifying to think that some kids might dedicate their lives to studying and protecting the oceans after getting an inspirational nudge from the saga of the telltale sneakers.