A grand hotel history A grand hotel history A grand hotel history

Some stories take you on an epic journey. Others follow the path of a character. This story, the tale of how a patch of University of Washington land in downtown Seattle became the site of a glorious hotel, travels across time.

By Hannelore Sudermann | December 2024

Downtown, dwarfed amid the glass-and-steel high-rise buildings, the stately Fairmont Olympic Hotel and the properties around it stand testament to early Seattle and the founding of the University of Washington. Its history is a fine tapestry embroidered with civic generosity, elegant details, extravagance, tales of celebrity guests and—very nearly—an untimely end.

In 1861, the site—within the wooded village of Seattle—was known as Denny’s Knoll. Businessman Arthur Denny was leading his fellow Seattleites in the charge to establish a territorial university, even though there were little more than 300 settlers. He donated 8 acres of his homestead, and his fellow pioneers, Charles and Mary Terry and Edward Lander, donated the rest to make up the 10 acres needed for a university campus.

John Pike, a settler from the East Coast, designed and built the UW’s original home, a two-story classically influenced clapboard structure. It had four massive columns in front, facing Puget Sound, and a cupola perched on top. An 1880s-era photo of the original university building shows it dominating a rough landscape of humble homes, barns and businesses.

The site served as Washington’s university for more than 20 years while the village around it turned into a town and the population soared to well over 3,500. In 1884, citing the “excitements and temptations” of Seattle’s waterfront district and a fast-growing downtown, the University’s Board of Regents decided to move the campus to a calmer, undeveloped location 6 miles north.

The settlers’ gifts of land in the present-day heart of downtown Seattle eventually became a boon to the fledgling university, but first it was a derelict patch. The regents were in a quandary with what to do with the land; they couldn’t sell it because of an economic slump. Instead, and to great long-term benefit to the University, they decided to lease the 10 acres for business construction and formed a public-private partnership with the Metropolitan Building Co. to make it happen. By 1909, the hillside—which became known as the Metropolitan Tract—had been regraded, and Beaux Arts-style commercial buildings sprouted up around it.

Long before Seattle had streets and sidewalks, the original Territorial University of Washington building stood on Denny’s Knoll. Built in 1861, the structure was demolished in 1910. Courtesy UW Archives.

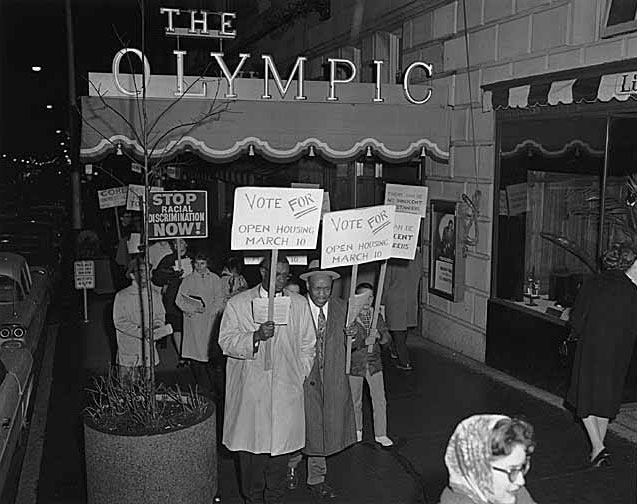

Civil rights marchers cross in front of the Olympic’s original front entrance in 1964. Courtesy Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI).

Meanwhile, the Klondike gold rush in the late 1890s funneled tens of thousands of men and women through the city as they provisioned themselves on their way to Alaska. With the arrivals of the Union Pacific and Milwaukee Road, Seattle had transformed from a small port city into an international trading post. The local leaders created a promotional pamphlet to lure new businesses and developers titled, “A Few Facts About Seattle: The Queen City of the Pacific.” The 40-page advertisement boasted booming industries of timber, farming, fisheries and maritime, noting that Seattle was a gateway to Hawaii and trade with Asia. It even celebrated the potential of hydropower.

In this time of optimism and opportunity, Seattle was ready for a luxury hotel—one where world leaders, entertainers and the wealthy elite could stay in luxury and steep themselves in the Pacific Northwest culture. Business leaders formed the Community Hotel Corp. to finance the project—and Seattleites were primed to support it. In the first week of fundraising, a bond sale garnered more than $2.8 million from nearly 4,600 subscribers.

The Seattle Times ran the contest that delivered the name: The Olympic. The real-estate developer who won donated his $50 prize back to support the construction. A famous New York architectural firm—George B. Post and Sons—designed the building, while the local firm of Bebb and Gould (Carl Gould created the 1915 plan for the UW campus and founded the UW’s architecture program) oversaw the construction.

The building went up in record time, with crews breaking ground in July 1923 and handing over the keys to the operating company at the end of October 1924. The final cost came to $5.5 million, plus another $800,000 for furnishings.

The building went up in record time, with crews breaking ground in July 1923 and handing over the keys to the operating company at the end of October 1924. The final cost came to $5.5 million, plus another $800,000 for furnishings.

Years later in her letter nominating the hotel for the National Register of Historic Places, Miriam Sutermeister, ’77, an architectural historian, describes The Olympic as “a monument to cooperative community effort” and the grand opening on Dec. 6, 1924, as “one of the most notable affairs in the history of the city.” According to one newspaper story at the time, guests from around the country flocked to Seattle to be the first to stay in the rooms.

The hotel boasted an oak-paneled, two-story lobby with an airy fine-dining restaurant at one end and a generous ballroom at the other. At least 7,000 people—many of whom had purchased stock to build the hotel—swarmed to see the grandeur for themselves. The project put Seattle on the map with lavish social events more typical of the East Coast.

In 1929, work was completed on the hotel’s 300-room northeast wing—just in time for the Great Depression. The operator filed for bankruptcy in 1931, and the hotel changed hands a few times until the 1940s, when William Edris, a UW Law alum and real estate investor, took control. In the 1950s, Western Hotels was running it.

The Olympic Hotel was a monument to cooperative community effort.

For 50 years, The Olympic was the city’s largest and finest hotel. It lived up to its promise, hosting princesses, pop stars and presidents. During a 1937 visit to Seattle, President Franklin Roosevelt used the hotel’s 11th floor as headquarters for his staff.

Decades later, President Kennedy, who came to town to celebrate the centennial of the University of Washington, created a “Seattle White House” by basing his staff at the hotel. “The Olympic: The Story of Seattle’s Landmark Hotel,” by Alan Stein and the staff at HistoryLink (an online history resource) boasts myriad stories of such luminaries as Elvis Presley, Joan Crawford and Martin Luther King Jr. Bob Hope stayed there in the 1950s when he served as grand marshal of the Seafair Parade. And Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, was a guest during a zany Shriners convention.

But by the early 1970s, developers were tearing up the city. They set their sights on The Olympic and other Metropolitan Tract buildings, which were showing their age. The White-Henry-Stuart building, part of the original Beaux Arts master plan for the UW land, was demolished to make way for the Rainier Bank Tower (designed by Minoru Yamasaki, ’34) and its shopping plaza. “We feared The Olympic would be next,” says historian Sutermeister.

- The Olympic Hotel under construction on the original site of the UW in May 1924. Courtesy Fairmont Olympic.

- An early menu from The Georgian Room, one of Seattle’s most elegant restaurants. Courtesy MOHAI/Webster & Stevens.

Seattle in the late 1960s and early ’70s lost some, but not all, of its precious structures, says Sutermeister’s husband, Professor Emeritus Grant Hildebrand. The Pike Place Market and Pioneer Square endured, thanks to grass-roots citizens led by UW architecture professor Victor Steinbrueck, ’35.

Seattle’s preservationists had watched the demolition of Penn Station in New York and were driven by the fear that bad modern architecture was replacing what was good, Hildebrand says. The Olympic is a strong example the Renaissance Revival style, he says. “The architectural quality is irreplaceable.”

A group called Allied Arts of Seattle, which included UW alumni and faculty, turned its energies to the UW land downtown. “We decided they had this whole 10-acre tract with these wonderful buildings that were going by the wayside, and we needed to do something,” says Sutermeister. The group publicly urged the University to preserve the historic structure. But not everyone was interested, Sutermeister says: “At one meeting, people fell asleep.”

Besides holding public forums and drawing attention to the threat, “the only thing we thought we could do was a National Register nomination,” she says. A nontraditional student with grown children, Sutermeister had enrolled at the UW to study interior design. She had relished her entry-level architecture classes and willingly took on the job of researching and writing the multi-page document nominating the hotel to the National Register of Historic Places. She dug into the archives at Suzzallo Library and sought expert advice from campus sources in crafting the document. The National Park Service gave its approval a few months later.

“We don't ever touch the architecture of the hotel. All of the original ornate carving and woodwork has been here from the beginning.”

Jennifer Sørlie, director of public relations and marketing for Fairmont Olympic Hotel

That nomination helped tip the UW’s regents into voting to preserve the hotel, she says: “That was a hurray.” Several members of the board had worked on the Seattle World’s Fair and had traveled through Europe, so they understood how beautiful and historic buildings enrich a place. “They had that sense that you can’t save them all—and you shouldn’t—but there are some to preserve,” she says.

In 1982, after a massive renovation that included tearing out walls and turning more than 750 small guest rooms into 450 generous ones, the revitalized hotel reopened as the Four Seasons Olympic and again was the belle of the city. In 2003, the hotel changed hands again. Legacy Hotels, the current owner, brought in Fairmont Hotels & Resorts to renovate and run it.

In 1982, after a massive renovation that included tearing out walls and turning more than 750 small guest rooms into 450 generous ones, the revitalized hotel reopened as the Four Seasons Olympic and again was the belle of the city. In 2003, the hotel changed hands again. Legacy Hotels, the current owner, brought in Fairmont Hotels & Resorts to renovate and run it.

The Fairmont’s latest renovation was a $25 million project that included restoring the lobby to its early glory with Art Deco-style furnishings as well as installing an upscale bar at its center. “We don’t ever touch the architecture of the hotel,” says Jennifer Sørlie, director of public relations and marketing for the hotel. “All of the original ornate carving and woodwork has been here from the beginning.”

A few months ago, she received an unusual request. Jay Cunningham, a UW graduate student completing his Ph.D. in human centered design and engineering and a former UW student regent, hoped to use the hotel lobby to have some professional portraits taken. “I’ve come to learn and highly respect the history of the Fairmont Olympic Hotel since it transcended as the first location of the University of Washington,” he wrote. “In this 100th year of the hotel’s history, I am excited to celebrate such an amazing milestone.”

She was tickled by the request. Lately, Sørlie and her colleagues have been knitting together projects to celebrate the hotel’s 100th birthday. Along with a gala on Dec. 6, the anniversary of the grand opening a century ago, the menu in The George (formerly the Georgian) will feature modernized versions of dishes featured on the menu in 1924: Waldorf salad, steak Diane and trifle. And there’s a special project in the works to renovate one of the guest rooms into a Husky-themed suite.

While some elements of the hotel are the same (such as the spectacular Spanish Ballroom) and others have changed (rooms are no longer $3.50 a night), the hotel, the land and the ties to the UW persevere. Today, as visitors walk through the front entrance from University Street, they pass an assemblage of bronze markers noting the history of the place: “On this site the University of Washington was established in 1861.”